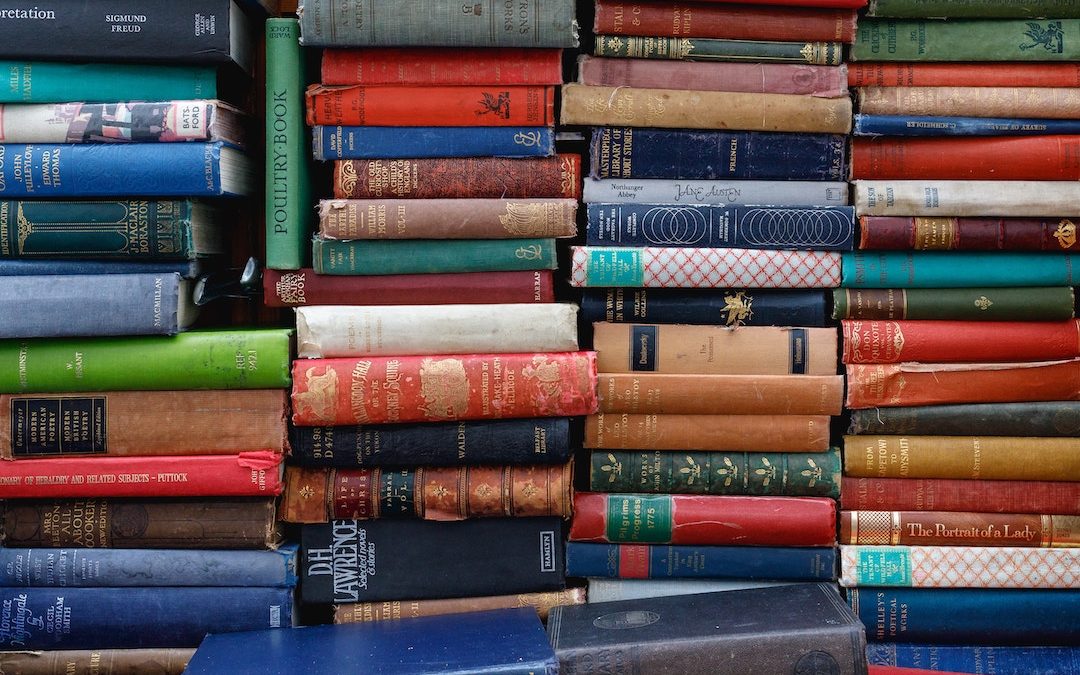

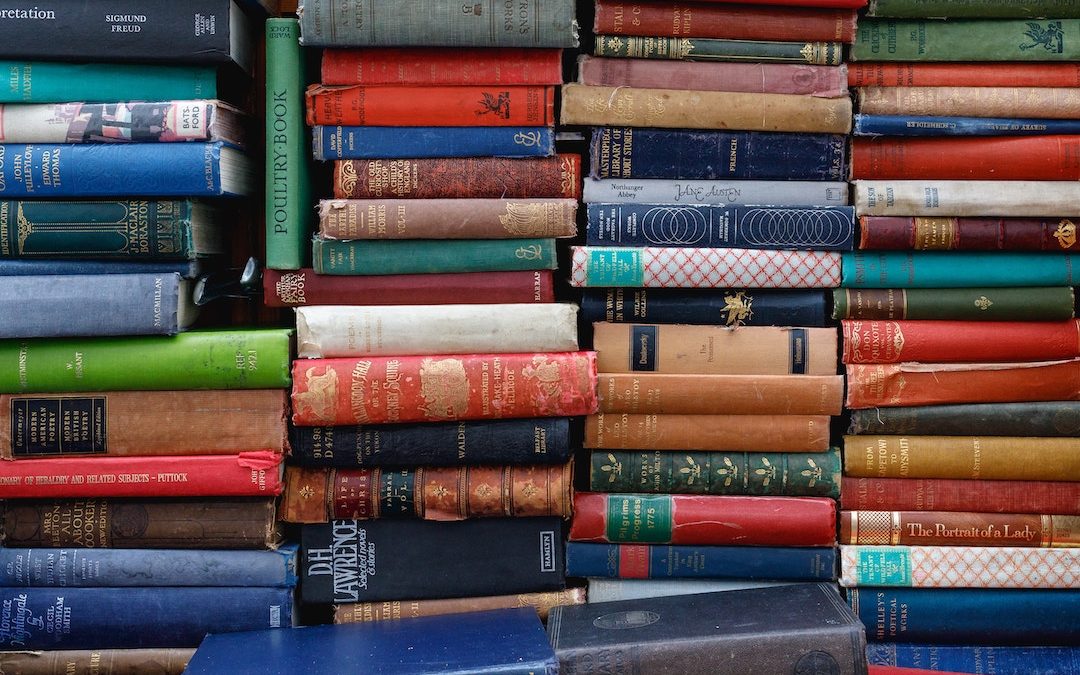

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

crack it open

there are worlds within pages

adventures and mysteries

and the essence of life

contained in history, science, story

teaching, widening memory,

affirming identity, all gathered

in a single spine

in a small collection of paper

so when a day has given

all it can give and there is nothing

left to do or see or glean or learn or try,

there is still

the book.

This is an excerpt from Textbook of an Ordinary Life, Rachel’s fourth poetry book.

(Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash)

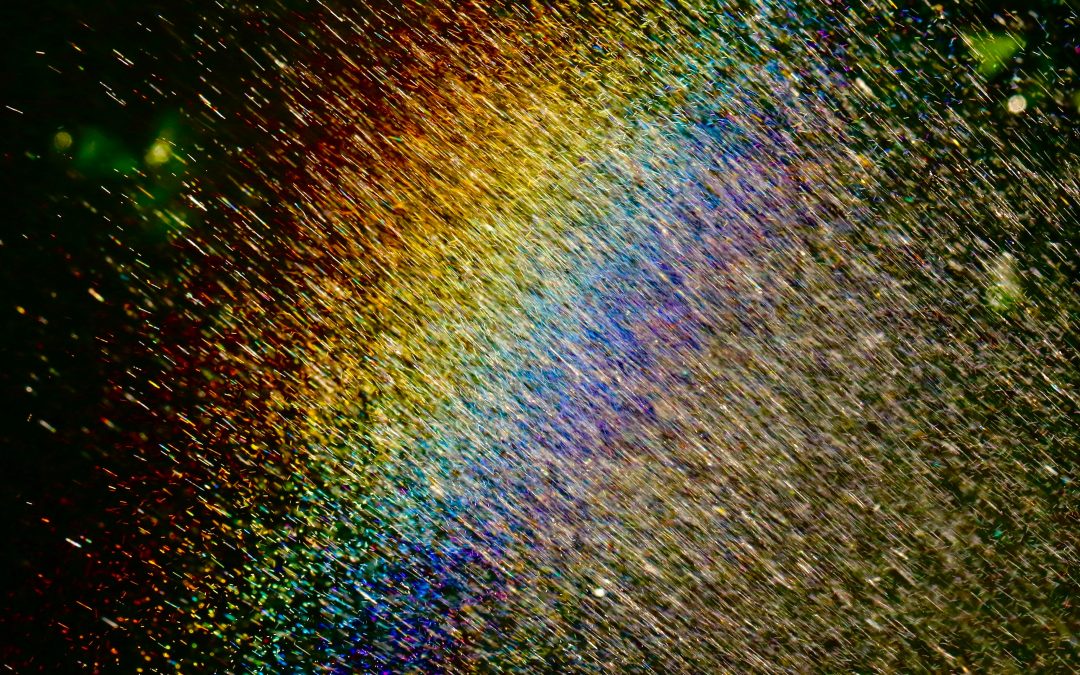

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I was an avid reader as a child. My mother would take us to our county library that was a fifteen-minute drive down two highways, and I’d stack the books as high as I could carry and take them all home and read them in less than a week. I read every Ramona book, Anne of Green Gables book, Pippi Longstocking book, every book by Madeleine L’Engle and Scott O’Dell. I was an obsessive reader; when I discovered an author I loved, I read every single book they wrote, told everybody about the author, passed books along to friends, hoping they would enjoy them as much as I did.

So many books—or authors, rather—shaped me in my formative years.

Madeleine L’Engle: I loved the science in her books, seeing a strong female character take center stage, reading the compassion and love and truth that flowed through her stories. Later, in my adult years, I would finish everything she wrote, including her adult novels and her memoir series, The Crosswicks Journals.

Scott O’Dell: The history in his books captured me, along with so many of his strong female characters (in Sing Down the Moon, Island of the Blue Dolphins, and Streams to the River, River to the Sea, among so many others). I loved reading about the culture of Native Americans, lives that were far removed from my own (though my great-great-great grandmother was Choctaw—and one day I will write about her).

The Brontës: How I loved Emily and Charlotte Brontë, the dark Gothic world of Wuthering Heights, the tragic world of the governess. Looking back on these books, the women protagonists weren’t necessarily strong, but they did everything they could in their limited circumstances during a time when women were not allowed much freedom.

Jane Austin & Virginia Woolf: I loved how they defied convention directly (Woolf) and indirectly through humor and satire (Austen). Their books still hold an important place in my heart today.

L.M. Montgomery: I loved the spirit of Anne, the way she approached life with joy and gratitude, her quirkiness, and how she defied convention in a charming, innocent way. She was brave and wild and free. I read every one of her books, with a relish I still remember.

Lois Lowry: I loved her fantastical worlds, the characters who broke free from oppressive societies, the way they found their place through struggle and their own resilience. Their journey was like a metaphor for my own life, and their victories made my own seem possible.

Toni Morrison: I still, today, read and re-read Toni Morrison, but I first discovered her in high school and read her obsessively in college. I read her for her expert use of beautiful language, the literary quality of her books, the strange threads she wove together, what she could teach me about not only the black experience or the poor experience (this latter of which I was familiar), but also the human experience.

Books told me who I could be, showed me my potential, and taught me how to write. They certainly became part of my multitude. It’s a privilege to think that maybe I can be a small part of someone else’s multitude.

What are the books that shaped you?

(Photo by Ed Robertson on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

Husband and I have been eagerly awaiting the time when we will be able to leave our sons at home without parental supervision. The oldest just turned ten, but I’m thinking this rite of passage is still quite a way off. The other day, when he offered to watch his brothers for half an hour so Husband and I could go for a quick walk and I asked him what he would do with his brothers if we took him up on his offer, he said, “I’ll just lock the twins in their room and then no one else is really a problem.”

Clearly he doesn’t understand what “babysitting” means.

He’s a fairly responsible kid, but he’s not all that observant. If his attention is stolen by anything—a bird in the backyard that he wants to identify, an idea that he has to act on right this very minute, a really good book—then the entire rest of the world is left to its own devices. He becomes efficiently and completely immersed in his own world.

The thought of having some time away while this son watches his brothers is very tempting. We don’t get many date nights. And this kid is the one who once told my mother that he wished he could figure out how to clone Husband and me so that one set of us could watch him and his brothers while the other set got to go out on a date. He knows we’re starved for dates and time alone, and he’s sweet enough to care.

Still, I’m too smart to sign off on Temporary Head of Household just yet.

The problem isn’t really him, either. The problem is that all six of my children are BOYS. Husband had a brother. I’ve heard insane stories about what brothers do together, and this does not help my son’s case at all. My sister’s husband had a brother, and his stories are even worse than Husband’s. What their stories tell me (and what I know to be true already) is that the things boys do are impulsive and careless and, I hate to say—I really do—stupid. Every now and then Husband, my brother, or my brothers-in-law will provide me with a glimpse of the little boys who still live inside them.

Take the Fourth of July in 2011, for example. These fine grown men of my family—all of them fathers, mind you—decided that year that they would drop some cash on fireworks—but instead of setting the fireworks off at night, they would do it during the day, using a PVC pipe as a homemade bazooka. This ended almost as badly as you might imagine—a fire started in the field behind our home. Thankfully, my stepdad, at the time, was a volunteer firefighter, and he managed to get it under control before anybody else knew of their prank. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him move that fast before, and I’ve known him since I was twelve.

This is exactly what leads me to believe that it’s quite possible I will never be able to leave my sons home alone.

Recently I asked this question on social media: What age is old enough for children to stay home alone? I got a variety of answers. None of my friends had a definitive one, because it’s really up to the parents and the kids. I know this. I remember staying home alone when I was eight, my brother was nine, and my little sister was five—but I was an old woman trapped in a child’s body. Also, there was only one boy.

Here’s what I imagine would happen to my house if my sons stayed home alone for any amount of time:

1. Someone would surely get hurt.

This is because someone would most likely decide to do something ridiculous, like climb to the top of the deck covering, which isn’t as high as the roof, and jump off with a trash bag they still think can make them fly; that someone might break his leg. Or someone would decide it might be fun to sword fight with butcher knives, since Mama and Daddy have always forbidden it and they’re the worst parents ever and only want kids to not have any fun; this someone might have his nose lobbed off. Or someone else would try to walk on the roof with their roller blades strapped to their feet because the slope of it makes the perfect ramp. That someone might break every bone in his body.

Boys think they’re invincible. Especially when they’re alone with no parent to talk any sense into them.

2. All the food would vanish.

When my sons are home, the most frequent phrase I repeat, besides, “You’ve already asked that question and I’ve already answered it,” is, “Get out of the refrigerator.” I suspect that as soon as Husband and I were to walk out of sight or drive away (one day), our boys would immediately open up the fridge and binge on the rest of whatever’s there.

We’d likely either come home to a completely empty refrigerator or a bunch of boys in prone positions complaining their stomachs hurt because they ate ten pounds of bananas on a dare or they found my hidden chocolate reserves or they drank a whole gallon of milk to see who could drink it the fastest without puking out their insides—which is what the boys in my church youth group used to do for fun on the weekends. They always did it at night, when their milk vomit practically glowed in the dark. Night or day, it was still stupid.

You’ll notice a recurring theme here.

3. They’d fight and one would threaten to run away—and actually accomplish it.

Since this happens often when Husband and I are home, I imagine that the same would happen if we were away for any length of time. The missing variable is Parent, but if there’s a Substitute Parent, I foresee it still being a problem.

And my sons don’t just threaten to run away: they do.

We live in a relatively safe neighborhood, and they have friends living all around it, so when they say they’ll run away, they’ll usually just go hang out at a friend’s house up at the top of the cul-de-sac. They’re easy enough to find; I let them have their momentary victory while observing their imagined escape.

But when a brother is in charge, he would probably not be quite so inclined to watch and “find” his missing brother, since the impetus to running away was the fight they just had. Brother In Charge despises Brother Who Ran.

The problem is not so neatly resolved.

4. Something terrible would befall the house.

Everywhere my sons go in my house, they leave their marks behind. There are fingerprints on windows and holes in the walls and ski marks on the carpet (don’t ask). One of them the other day “accidentally” slammed the back door too hard, and a picture frame fell off the wall and shattered at his feet. He was shocked to know that he had such power.

Boys, as any parent knows, don’t think about the fact that if they climb onto a bookshelf full of books, it might actually fall over (if it’s not bolted to the wall—and sometimes even then). If they try to stack two chairs on top of each other, even when the makeshift “stool” is propped against a wall, they will still fall and, for their efforts, punch a new hole in the wall. If they try to do a pull-up on the open cabinet, that cabinet will rip from its hinges.

They don’t think about what they’re doing until there’s a gaping hollow in the door where they thought it would be funny to kick it closed. They don’t think about what they’re doing until there’s a shower curtain bent in two, because they wanted to see if it could actually support their weight. They don’t think about what they’re doing until the mirror is shattered in front of them because they thought it would be funny to throw a metal car at it.

Without parents at home, all my house’s protection vanishes.

If my sons were left alone, the chance that they would do something stupid and irresponsible increases, by default, by about one thousand percent.

Everybody knows that boys need the loving hand of a wise parent to keep them from doing something reckless. They only have the capacity to consider how cool the idea would be. You want to see what it would be like to jump from the roof to the trampoline? I’m game. You want to ride a skateboard down the stairs? Yep. Me too. You want to set off firecrackers from a PVC pipe? Let’s do it.

What could possibly go wrong?

Every now and then, my ten-year-old will try again. He’ll tell us to go ahead and go out on a date. He’ll take care of his brothers—for a price (ten dollars. He has a cheap going rate). We thank him for his kindness and consideration and politely decline for now.

And, possibly, forever (but I really hope not).

This is an excerpt from If These Walls Could Talk,the fifth book of humor essays in the Crash Test Parents series.

(Photo by Stephen Radford on Unsplash)

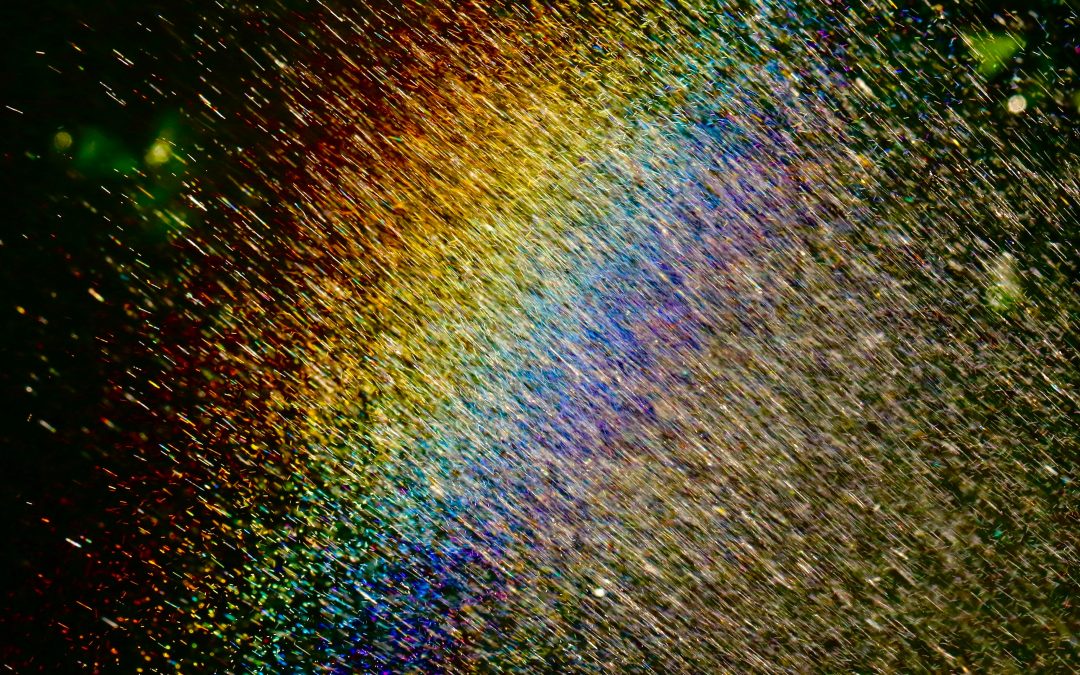

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

It’s time to go!

We were on our way out the door, running late as usual, because two of them couldn’t find their shoes. One of my least favorite activities, when we’re running late anywhere, is spending time on the Shoe Search—mostly because I can’t get deeply enough into my sons’ minds to imagine where they might have left their shoes. Where would I leave my shoes if I were, say, the four-year-old? No idea (They were under a towel in his older brother’s room, along with the swim trunks we couldn’t find last night).

We finally had everyone clothed and shoed and were now ushering them out to the car. We have only recently arrived at the stage where every kid can buckle himself and my husband and I can simply slide into our seats and go, provided everyone does buckle.

But my four-year-old was taking an unusually long time to actually get into the car. He is one of the most compliant children in the bunch, doesn’t fight us on most instructions, so I reminded him it was time to get in the car, come on, we were late.

“But look, Mama.” He pointed up to the sky, and I saw it: a rainbow. Two of them, really, one arcing over the other.

Maybe I would have seen it, eventually, once we got on our way. Maybe we would have driven right into it, maybe it would have been just as bright and magnificent, maybe we would have all shared that moment with a breath and an exclamation of awe. But who is to say? Maybe I would have, instead, been staring at the clock, lamenting about how we should have left half an hour ago, I hate being late, we better not miss anything important. It’s impossible to say which track my mind would have taken.

But what really mattered, in that moment, was to stop and stare and marvel—which I’m happy to say I did.

The bottom rainbow was glowing—you could see every color as though shaded with a marker. The top one was opaque but still colorful. The air smelled musty, like rain, and I felt a drop on my hand. But it didn’t matter—I remained, staring at beauty.

So much of my life is rushing between one thing and the next—finish the laundry before heading up to work in my bedroom, washing up the dishes before beginning story time, racing out to the car to beat the clock so we can make it on time to wherever we’re going.

How much do I miss in this constantly rushing state?

Fortunately, my children move at one speed: slow. That means they often require me to move slowly as well. And rather than be annoyed by that, I want to be glad.

So I picked up my four-year-old (he won’t be picked up for much longer), and we named the colors we could see: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, pink. He laughed about how this is the same way he draws rainbows. I laughed about how he was right.

Everything else, for that moment in time, could wait.

(Photo by James Wainscoat on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I’ve started running again.

It began with a handful of miles—three or four, then quickly escalated to the six I used to run in college, when I would get up every day at five a.m. and run six miles before classes. My body remembers the routine; it’s moved back into the ridges carved out over four years of my past.

The running gives me a sense of control. There’s so much in my life that feels somewhat out of control, and it’s comforting to have that segment of time—an hour, maybe more—when I have almost complete control—over my breath, the distance I run, the speed with which I run it. I belong to myself, and my mind stills and it is only the steps, the breath, the path before me.

Running connects me fully to a moment, but it’s not only that mysterious connection that calls to me on the days I don’t schedule a run. It is the past, too.

For twelve years I have been a mother. I have given myself fully to my children. I have coaxed them through tantrums, taught them about emotions and how to read, aligned myself to their desires and needs so I can nurture and mold them into independent human beings who think and feel and decide for themselves. There is still a way to go; my oldest son is twelve, my youngest is four. They still need me, but in not quite the same way.

Two years ago, five years ago, it would have felt inconceivable to me that I would wake at five a.m. and spend an hour running six miles or more. The time to myself was short and stunted. If I had an hour to myself, I would not spend it running.

But time has widened now. There are moments when I find myself alone in my home library, when my sons are playing happily in the backyard and I can open a book and read a page or two without interruption. There are moments I realize I’ve been staring into space, daydreaming for half an hour and no one needed me. There are moments I can bookmark to run.

Maybe all this means I am losing part of myself—the part that was an ever-present, always-on-duty mother. My sons seek their father’s advice for things now, not just mine. But maybe it also means that I am gaining a part of myself, returning to a past me, remembering who I am, who I was—this person who looked forward to running six or more miles a day for the peace and quiet—the freedom—it gave her.