by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

It is the words that stay

long after the faces have faded;

the words are the treasures,

of such great worth that

when used poorly they do not

simply fade into a background

but stand like sentries

at the entrance to a heart,

beating out all other words

intended for good

Grow a thicker skin, they said,

but, alas, I cannot. This is me,

the thinnest skin around,

everything sinking in like it

holds the key to me, or, rather,

locks the truth in a dark dungeon

And so it is not easy to simply

grow a thicker skin

How does one do such a thing?

How does one put on dismissal,

become someone they were not

only moments before,

ignore the ones who

slash and scrape?

They say they cannot

teach me anything,

that the words must be

burned in a blaze,

but this, too, is not so easy

The words are my blaze

burning away my pieces,

charring sacred spaces,

consuming who I was

But perhaps this is not

so awful a purpose at all

It is only in the burning

that one rises from the ashes

in a splendid newness,

with a stronger construction,

as a more secure human being

And so

I let

them

burn

This is an excerpt from Textbook of an Ordinary Life: poems. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by Austin Neill on Unsplash)

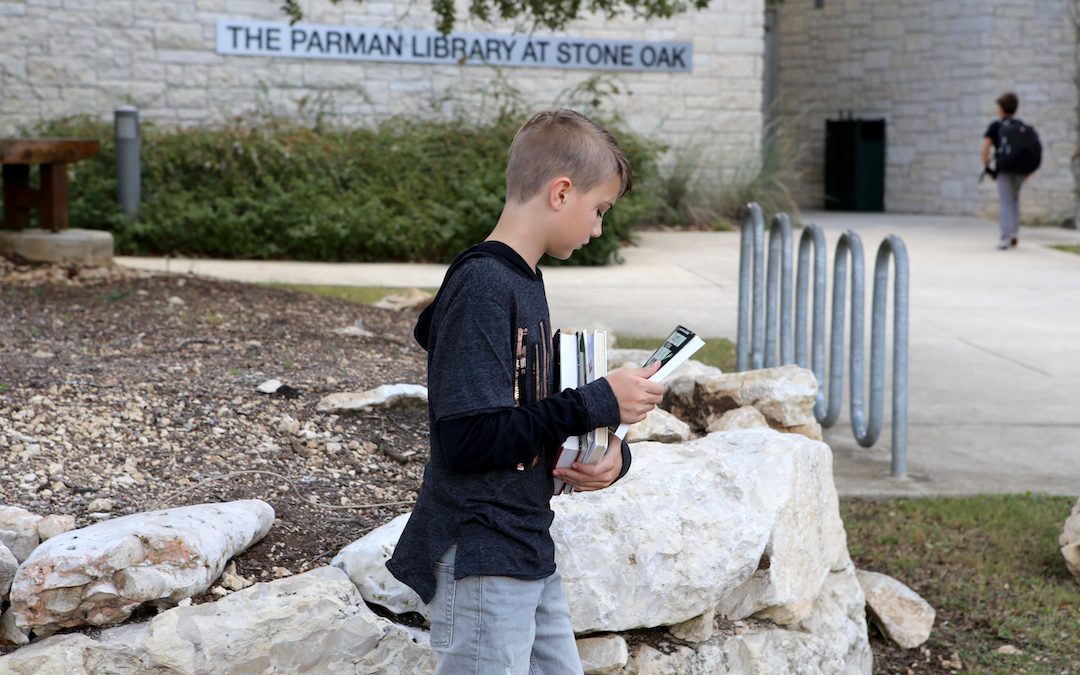

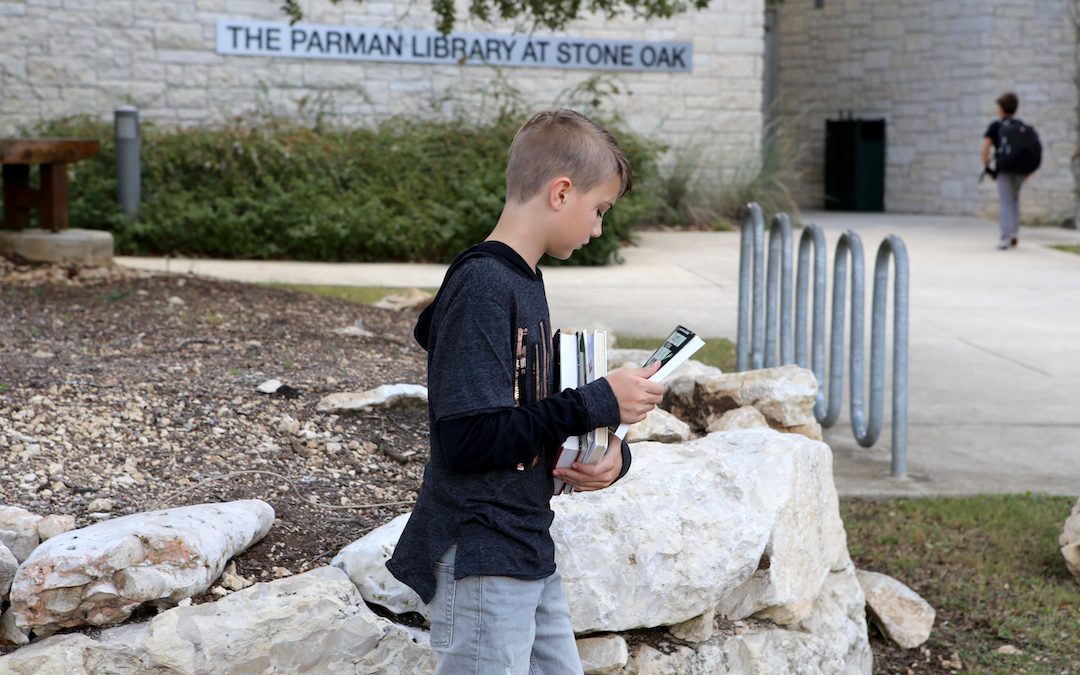

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I could feel it coming: the nervous anticipation of the first day of school.

When I was a kid, I threw my nervous energy into choosing my first-day-of-school outfit (which got progressively more complicated as I grew older and cared more about first impressions). I would lay out my clothes, visualize the next morning, plan for the unexpected.

My sons are not so conscientious. I am the one who usually lays out their first day of school outfit, not because they can’t but because for now they humor me with a special coordinated outfit (which is not the same as matching, by the way; in their coordinated outfits I try to choose pieces that account for their color and style preferences and their personalities, within reason. No, the 8-year-old cannot wear a fluorescent orange Pokémon shirt the first day of school.) Once I’ve released the outfit, which I keep in my closet for security purposes until the night before the first day, they will stare at their shoes, drape socks over the sides, run their hands across their new backpacks, presumably thinking about what the next day will hold—or perhaps thinking nothing at all.

This year we had a brand new experience for the first day of school: my oldest son was entering middle school. So the nervous energy that accompanies all first days of school held something else: a tinge of fear.

He hovered outside our bedroom, meandering in every so often so we could tell him, gently, that he needed to get to bed so he would be well rested. He lingered. He paged through books on my bedside table. He examined his fingernails.

I could tell he wasn’t quite ready to close the door on summer. He knew—he knows—that life from here on out will be much different.

Growing up isn’t always easy. I daily watch my sons pull against the tether that keeps them dependent on me, ever ready to assert their own independence, even if they’re not quite capable yet. And then a new stage of life presents itself, and freedom widens, and they huddle at the precipice, peering over the edge, questioning whether they are actually ready. They wonder if they have what it takes to fly. They assess how hard the ground might be, because their safety net isn’t quite as thick as it used to be (though this is just an illusion; they always have a thick safety net).

At some point, I drew my son nearer to me. I held his hand. I did not tell him he would be fine, school would be fun, everything would be easier than he thinks; none of that is assured. I only said, Remember who you are.

He knows what this means. Since our kids were young, any time we drop them off somewhere we will not be, we have told them, Remember who you are: strong, kind, courageous, and mostly son. It’s a phrase they have heard all their lives. It’s a phrase that speaks of love—that they will always, no matter what, be loved.

An easy, fun, even good year is not assured my son; that’s not how life works. But what is assured is that at the end of this next season of life, he will have grown, learned, and walked deeper into who he is. And no matter what kinds of twists and turns this year holds, no matter where he goes or what mistakes he makes or victories he has, he will never be anything other than who he is: strong, kind, courageous, son.

Worthy.

Half an hour past his bedtime, he finally found his way back to his room, filled his diffuser with essential oil, and read until he fell asleep, covers pulled up to his chin, book marked with a finger.

The same kid—but different.

(Photo by Helen Montoya Henrichs.)

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

I’m a very task-oriented person. I make my goals, I make my list of tasks to support those goals, I work myself every hour I have and don’t quit until the clock says my work day is officially done.

This means that while I accomplish a ridiculous amount of tasks during my working hours, I also creep close to burnout frequently.

I solve this problem with rest.

Every six or seven weeks (depending on my sons’ school schedules—I like to match up my time off with their holidays from school) I take an entire week off work. I don’t do anything work-related. I read some books, hang out with my kids, play some board games, maybe even do a little sewing. I play. I take naps. I breathe.

I call these weeks Sabbaticals. They are my time to recover from my weeks of focused and intentional work.

I’m coming up on the last Sabbatical of the year, which extends for two weeks, as a sort of celebration and goodbye to the previous year and welcoming of the new year (plus, my kids are out of school for two weeks and counting down to Christmas Day, and getting any work done is highly unlikely). I use this two-week break to make New Year goals, prepare for the holidays, and schedule my next year—including Sabbath weeks.

When you spend so many weeks (even if you don’t have many hours in a day) in such focused and intense work, burnout is a given. Add to that family life and adult responsibilities and the unpredictability of life, and it’s a wonder any of us get anything done.

Intentional rest opens up the space to breathe again—which is necessary to create.

Resting keeps me focused on and energized for the work ahead of me—and I’m always ready to get back to work once those seven days (and especially the fourteen days) have passed.

(Note 1: I don’t completely forbid myself to write during my Sabbaticals; writing often keeps me sane when I’m home with my sons. And creative work is never really predictable. If the urge strikes me to write something—as long as it’s not a project I’m currently working on—I write. It’s usually something playful or silly or experimental that could potentially become something greater someday. I never want to lose that opportunity to create something new, but I do want to rest well.)

(Note 2: Your Sabbatical will look different than mine. There is no one right way to do it.)

(Photo by Angelina Kichukova on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

books on the floor

books in a chair

books all around

stretch out

on the floor

let the kids

climb on a back

no matter

how weary

get those accents

ready

all the acting

cued up

voice prepped

for action

and then

the giggles begin

woven around story

and knowledge

and magic

this is how

to read to your children

This is an excerpt from This is How You Know: a book of poetry. For more poetry, visit my starter library, where you can get some for free.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

The holidays are fast approaching. I will be spending time with people I love very much but whose beliefs and ideologies and values and political persuasions don’t always line up with my own. I have tried to ignore to which sides they lean and belong, but some things are more easily hidden than others. I have been downright shocked sometimes at the things that are said and done in the name of “righteous” conviction.

In the past few weeks I’ve found myself backing away from social media, disengaging from the dividing lines that seem to mark us as a contemporary society, shielding myself from the angry news, the dehumanizing words, the conversations that feature more talkers than listeners.

I am, by nature, a peacemaker. I don’t like to step inside conflict, to shake up waters that I’d rather remain tranquil and still. And sometimes that means I haven’t spoken when I really needed to speak, when I felt the words damming up inside, when I noticed that someone was bulldozing another’s identity.

Identity is a shaky thing in the first place; we’re often not entirely sure we’ve really found it. We uncover it, we bury it, we uncover it again. We don’t always live into it perfectly.

When our identity is further shaken for the purpose of corroborating right or wrong in an argument that will prove ridiculous in the grand scheme of things, I balk. Not always publicly, but always privately.

I know what I’m supposed to speak; the words come easily for me. But sometimes I’m too tired to be brave. And, besides, what about peace?

I’ve spent quite a bit of time recently thinking about what it means to be a peacemaker. Thinking about how we preserve dignity and honor in the face of ever-present conflict. Thinking about my own convictions and where they line up with peacemaking.

Sometimes the best way to understand something is to think about what it doesn’t mean.

Peacemaking doesn’t mean compromising on my values. It doesn’t mean leaving behind my ideals. It doesn’t mean pressing pause on my mission, which can be summed up by e.e. cummings’s wise words: “love is the whole and more than all.”

It doesn’t always mean remaining silent.

The other day my husband was standing at his computer, scrolling through Facebook, though I’ve told him it’s not a good time to be on Facebook and we have better things to do and create. He saw a post from a friend that shocked and disappointed him. He said, “How do I keep from spending all my time on social media, helping people look at facts instead of mere opinions?” He was asking, because he wanted to set this friend straight, to present the factual details that could be used to create a more informed opinion—regardless of whether or not that opinion actually changed.

It’s a difficult question to answer, and the answer will be different for everyone, at different times. Some weeks I know I have better things on which to train my focus; some weeks I feel compelled to impress knowledge and compassion onto and into hearts. Sometimes my peacemaking looks like remaining silent; sometimes it looks like bringing a sword (metaphorically speaking, of course).

Sometimes the peacemakers are the people who speak most boldly (in love, remember), let that truth unfold in the hearts of hurting people, and usher in peace that is large and expansive enough to overcome fear and hate and dividing lines. Sometimes our very presence is peace: we show people they are not alone, that they can endure, that we are all the same, deep down. Sometimes we become peacemakers in the things we create.

And we must not neglect to do what is necessary for ourselves, to remain at peace. We cannot be peacemakers if we are not ourselves at peace. For me, that looks like scheduling a time of meditation every morning. It looks like taking frequent Sabbaticals from social media. It looks like culling acquaintances from my friends list. It looks like spending time with the people I love, in person, here, now.

In becoming peacemakers, we must have standards: we cannot compromise who we are, for what we stand, and what we know of love—that it forever endures, no matter what. That is as true for us as it is for “them.”

I hope you have a wonderful holiday season full of peacemaking and gratitude.

For more writings like this, sign up for Rachel’s e-newsletter. You’ll get a some free books and short stories, too. Visit her Reader Library page for more details.

(Photo by Jonathan Meyer on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

One might say that I

started out with

all the wrong cards.

Poor parents.

Absent dad.

Little to do in the world

but become the very picture

of my parents before me.

How does one break free

of the cards one has

been dealt?

In sixth grade, my English teacher

told me I had a talent for

dreaming up stories.

In seventh grade, my English teacher

drilled me on proper grammar

and punctuation and spelling,

said I had a gift.

In eighth grade, my English teacher

told me she wanted me to do

some extra writing work,

to develop my emerging skill.

In ninth grade, my English teacher

took my essay on Dickens and

read it to the class while I hid out

in the bathroom, mortified.

He tacked it to the board

as an example of a good critical essay.

In tenth grade, my English teacher

gave me a list of books

I’d need to read

to become a better writer,

said it was optional,

no grade attached.

I read them all.

In eleventh grade, my school counselor

gave me a college application

and said, No pressure.

It requires an essay.

I wrote eight hundred words

that night, used the story

of my parents’ divorce

to prove that all bad deals

could be turned

into good ones.

The trick to life, you see,

is playing a

poor hand well.

This is an excerpt from Textbook of an Ordinary Life: poems. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by Soroush Karimi on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

It’s good to feel needed as human beings. We need to feel needed, at least some of the time. It’s how we recognize our value in our specific worlds.

Kids need parents for practically everything—at least for a while. They need us for crossing the street, even though they’re nine and have done it a thousand times before (they probably just got lucky there were no cars coming all those other times). They need us to tie their shoes, or, if they’re not feeling lazy today, to at least stand there and watch them do it on their own. They need us to watch when they’re flipping over the side of the couch in what looks like a professionally-trained gymnast move, because if no one sees them, did they really just do it?

When kids start growing up and doing things for themselves, it can feel a little disorienting to suddenly have so much more time on your hands in the mornings. You no longer have to make their breakfast because they popped a slice of toast in the toaster oven and spread half the stick of butter on it when it was done. If you’re anything like me, you’ll feel a little sad that they’re not whining about how you’re not pouring their glass of milk fast enough because they just did it for themselves. You might even feel a little sad when they don’t forget their lunch as they’re walking out the door to school because they’ve finally learned the routine, after four years of practicing.

It sounds crazy to think that kids’ independence would cause a parent sadness. Isn’t independence what we crave when our three-year-old follows us around the house scream-crying for the toy his brother took away or our five-year-old bursts into the bathroom because he didn’t “want us to be scared while we were going pee?”

Well, it happens. Trust me. Now that my nine-year-old takes a shower in the morning and I don’t have to check behind his ears to make sure he actually used soap, I feel a little sad that I have three extra seconds on my hands.

But if you ever start feeling too sad about your kids’ emerging independence, all you have to do is get on the phone. This will provide the perfect opportunity for them to engage in a heated argument about the red LEGO piece one of them took from another—because none of the other five billion red LEGO pieces in their collection will work—and, even though you’ve taught them effective methods of conflict resolution, they won’t be able to resolve this argument with anything but a good old-fashioned fist fight. And the person who will most likely be on the other end of the line is a receptionist for your kids’ pediatrician’s office, who will politely try to ignore what’s going on in the background even while you’re asking her to please repeat the confirmation for that appointment, for the fourth time.

You could also press play on an audiobook or a podcast you’ve been meaning to listen to or (bless you) sit down to actually read a book while your boys are outside, entertaining themselves with sidewalk chalk. You can be sure that as soon as your finger hits the play button or your backside hits a chair, one of your children will come screaming into the house because he tried to smash the blue stick of chalk under a giant rock and he accidentally missed and smashed his toe instead and now it’s probably going to fall off and he actually wishes it would, because he can feel his heartbeat in his pinkie toe.

Well. At least you read a whole sentence this time.

You could sit down on the toilet. That’s when your kids will need you to get something down from a cabinet they can’t reach—like a cup, which they’ll use, as soon as you disappear back into the bathroom, to fill with water, submerge twelve LEGO pieces and the house keys (without mentioning this to you), and stick in the freezer just to “see what happens.”

Or you could sit down to eat at the same time everybody else in your family sits down to eat. What a luxury, right? You no longer have to eat cold dinners. Unfortunately, this is probably the time when your kid, who’s been drinking out of a regular cup for three years now, will accidentally knock over a brimming-with-milk Iron Man cup, because he was trying to reach across the table for more spaghetti before he’s even inhaled his first helping. And you’ll have to do what you’ve always done. Hand him the paper towels, watch him mop it up (not much more skillfully than when he was three), and then mop up behind his mopping, because perfection is the name of your game.

Or maybe just start talking to your partner, assuming that, because the kids are capable of caring for themselves now, they won’t need you and you can actually finish a whole conversation in one sitting. But this is when they’ll remember that they forgot to tell you an entire minute-by-minute narrative of how their day went, and even though they’ll politely wait for you to finish before they’ll start their story, they’ll also stare at you the whole time they’re waiting, and you can actually feel that wide-eyed gaze burning holes in your head, stealing your thoughts. You’ll look at your partner, shrug, and listen to the random observations of a six-year-old before trying to remember what it was you needed to say to the other adult in the room (it will take you three days to remember).

Or you could try to go to sleep. And then they’ll knock on your door with such urgency that you think this must surely be an emergency, and you’ll fly out of bed, fling the door open, and see before you no one who is bleeding, passed out, or dying, or any kind of fire anywhere to be found—all emergencies as defined by your Family Playbook. No, sorry, baby, your stuffed animal losing a back leg because you and your brothers were playing tug-of-war with him is not an emergency. Go back to bed.

Get used to your kids doing anything on their own, and actually start missing the times when you were needed, and almost without fail, they will make sure you feel needed again. Think I’m kidding? Start missing changing your baby’s diaper. Someone in your house will wet their pants in no time.

It’s no easy thing to pass from the I-need-you-all-the-time stage to the I-need-you-sometimes stage and then, inevitably, to the I-don’t-need-you-at-all-anymore stage. It’s also hard not to wish for an easier stage when you seem to be stuck in the I-need-you-all-the-time stage. I’ve been stranded there for almost ten years. I’d like to sit down for five minutes, please.

Also, stop growing up so fast, kids.

Just five minutes where you don’t need me? Five seconds?

But here, let me do that for you, baby.

This is an excerpt from Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On, the fourth book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

We’re sitting around the table, talking about our days like we always do, when my husband says, “We got some negative podcast feedback today.”

“Oh, yeah?” I say.

He tells me about this product manager with Facebook, who wrote in to say that as much as he wants to recommend the show to his friends, he just can’t do it because of my husband’s involvement. My husband, according to this man, hasn’t had the kind of success people would expect from a business owner giving business advice.

This exchange comes at the beginning of our meal, just before we get to our thankfuls, and it thoroughly and completely derails me. So it gets to my turn, and I can barely think of anything that deserves my thanks, my whole mood shot through with rips and holes and great big tears. I think about my lost job and our money worries and what might or might not come next in the lineup of success, and my stomach twists, way deep down.

My husband knows, of course, because he’s that kind of man. He smiles and says, “It doesn’t really matter. I know I’m successful.” And I know he’s right and I know he knows, but something about it just won’t let me go.

That word, success, is a dirty one, snaking all through my past.

A man’s hasty criticism sends it striking again.

///

I spent my four years of high school constantly stressed about grades—because, you see, I wanted to go to college, and I knew my mom and stepdad could not afford it. I needed to graduate valedictorian, because it was the only way I would make it to college, since valedictorians in Texas are given free tuition at their college of choice for at least the first year of attendance. So I watched those class rankings, every six weeks, like they were life and death.

I came out on top, and my classmates held an election right before graduation for all the yearly yearbook awards: Most Beautiful, Most Talented, Most Athletic, Most Popular. They voted me Most Likely to Succeed.

“Because you’re smart,” they said. “Because you know so much. Because you always find a way.”

They could never have known the pressure that award carried in its flimsy paper particles and its forever photo buried in a maroon yearbook.

I went off to college, one hundred twenty-six miles from home. I had never been away from home longer than three weeks at a time, and by month two, I wanted so very badly to go home I cried myself to sleep every night. I missed my mom. I missed my whole family. I missed all the familiar. But I could not go back, because that is not something a person who was Most Likely to Succeed would do.

So, on the worst nights, I pulled out the coloring page my fifteen-year-old sister had sent me, the one with Garfield and Odie colored in muted oranges and yellows, the one that said, “Wish you were here” in a little cloud bubble beside Garfield’s scowling face. And I whispered what I could never, ever admit to anyone.

I do, too.

///

Success comes breathing down our necks, and its breath is foul and suffocating and inescapable—because it is everywhere in the world. In magazines profiling the “most successful” people in the world, according to how much they’re worth in a year’s salary. On billboards where famous personalities tell us to watch their shows. In books and on screens and next door to us, where the Joneses live.

Success looks like how big a business you build in the least amount of time or how much money you have in your bank account. It looks like big houses and luxury cars and a name that means something when spoken.

Success, the way the world defines it, carries pressure in its scales. It can hypnotize us into believing its shallow lies. It will tell us what to do and how to live and who we should be.

I can see its venom weaving in and out of all my younger years. I took jobs and turned others away because of it. I bought a two-door silver five-speed car because of it (two doors looks more successful than four, silver is sleeker than blue, five-speed is faster than automatic). I wanted a bigger ring because of it (because the bigger the diamond, the greater the catch, right?). I fell hard into its nest.

And then something happened.

///

As college graduation approached, I did not worry like all my friends. I already had a job at the Houston Chronicle. I had a brand new car and thousands in the bank. I had an engagement ring on my finger.

I was going to be prolific.

For a time, that Most Likely to Succeed award felt just right. I was proving it true.

Money? Check.

Prestigious job? Check.

Husband? Check.

By the end of that year, I would add several writing awards to the list, and later we would start a band and play around town and then the state and then all the way up through the Midwest.

On the road home from a gig in New Mexico, my cell phone rang. It was my mother. My grandmother, she said, was dead.

My grandmother, the one I’d lived with for a year during my childhood, when my parents were divorcing. My grandmother, who had offered her house for six months during that Houston Chronicle job and cried the day I left for San Antonio’s newspaper. My grandmother, beside whom I was too busy to sit those nights she watched the news—instead holing away in a room planning my elaborate Cinderella wedding.

Her death devastated me. I counted back all those married months, forty of them, and I had only seen her three times—once after we returned from our honeymoon and she picked us up from the airport and begged us to stay the night, because it was too late to drive from Houston back to San Antonio and she knew we were tired from the flight, and we said no, because we wanted to get home and get on with our married lives; once for our year anniversary trip to Disney World, when we needed her to drop us by the airport; once when she came down for my firstborn’s baby dedication, the day I watched her hold him from the stage while I cried through singing the lullaby I’d written for him.

How had this happened?

My grandmother was a school accountant of some kind for all her working life. She never made much money, never kept any money in savings because she was too busy buying her grandkids gas so they’d drive to see her or treating her kids to dinner or writing a check for a granddaughter’s wedding dress. She stayed put in a no-promotions job because she enjoyed the summers off and the way she could keep her grandkids for whole weeks at a time.

I learned something the day we all gathered to celebrate her life. I learned, or maybe I always knew, that she was the very definition of success.

///

Success lives in who we are, not what we have.

Success is found in the way we look at our spouse in the middle of an argument. It’s found in the way we talk to our children when they’ve done something wrong. It’s found in the relationships we keep with family and friends and neighbors and strangers. It’s found in the deepest spaces of a heart. The world, the ignorant words of others, the critical eyes of people, can make us forget this.

Sometimes people will look at our choices—having and raising six children, turning down a promotion because it would take too much time away from those children, remaining a one-car family because we don’t want the debt—and stamp us unsuccessful because we don’t look like the ideal. But success can never be measured on the outside. It is held within.

I wish I had realized that sooner in my life. I will never get back the time I spent pursuing a twisted version of success.

But I can redeem it now.

So tonight, in front of my boys who will one day be men with a whole world and its people trying to tell them what success means, I look my husband in the eye and say, “You are successful in all the ways that matter.”

And then I tick them off, all those successful attributes so much a part of who he is.

We may not have a bank full of money we couldn’t spend in a lifetime or two luxury cars sitting out front or a vacation home in that place we always wanted to live. But what we do have, this life full of laughter and presence and joy, is so much better than all that.

The world can take its success definition and cash it in for an empty life.

I’ll take my full one any day.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Jungwoo Hong on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

Beginnings

It’s the end of one

year and the beginning of

another, fresh start.

Time

I can’t grasp the years,

though the days stretch long; time’s a

shadow left behind.

Years

They say the days are

long but the years are short, and

I understand now.

Endings

We’ll watch a closing

door like it’s the last one—but

one always opens.

These are excerpts from Life: a definition of terms, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of volumes for free.

(Photo by Aron on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

I have a favorite child today.

It’s the boy who carried my laptop down the stairs because his mama’s foot is broken and he knows she needs a free hand to hold onto the stair rail so she doesn’t fall again. He carries it so carefully his eyes are opened wide in concentration, and he places it exactly in the right place on the couch where he knows I always sit at this time to feed the baby.

He’s my favorite until it’s nap time and he won’t put away the LEGO pieces he wanted to play with and then, when my back is turned because I’m putting the littlest one down, he smuggles that (quite impressive) creation under the covers and thinks I can’t hear him snapping and unsnapping pieces.

Then my favorite is the one who stacks his books into a neat little pile at the foot of his bed instead of scattered all over the floor like a book carpet, who fell asleep right away and didn’t need any reminders that right now is nap time and not play time.

He’s my favorite until he decides to wake all his napping brothers, because he fell asleep first—which means he’s logically the first one awake again—and he looks at the hangers in his closet and thinks they might be a perfect tool to use in his wake-up plan, so he craftily removes all the clothing from the hangers, arranging shirts and pants and even shoes in what looks like crime scene positions all over the floor and then rains the hangers all over the faces of his sleeping brothers.

Then my favorite is the one who remembers to go potty before we get in the car to go pick up his older brothers from school and isn’t hysterically whining about how badly he needs to go potty and how he really, really, really doesn’t want to go in his pants, which makes panic close off the back of my throat, because I really, really, really don’t want to clean up a toddler’s feces, but there’s a school zone and kids running everywhere and no accessible bathroom that doesn’t require unpacking everyone and at least fifteen minutes of wasted time, judging by the school pick-up line.

He’s my favorite until we get back home and I’m helping his older brother put some things away and he decides he wants a cup instead of a thermos, even though, to date, he’s only ever spilled a cup of anything and we’ve told him he needs to be a little bit older before he drinks from a lidless cup, and he does exactly what he nearly always does: spills it, and two boys slip in the water he didn’t tell anyone was there.

Then my favorite is the boy who goes outside to play and comes back in with a wildflower he found in the yard that reminds him of me because it’s so beautiful and he just had to pick it so I could put it in my hair and match beauty with beauty.

He’s my favorite until he comes back downstairs in his third new outfit since he got home from school half an hour ago and proudly tells me he put both the previously worn shirts and shorts—worn for a collective ten minutes—in the dirty clothes hamper and not on his floor, and, also, he’s wearing twelve pairs of socks.

Then my favorite is the one who lopes downstairs to ask if I want to listen to an audio book with him, because he knows I love reading while I’m cooking dinner and setting out plates, so I say, yes, of course, and we share a story while he sits at the table building LEGO creations and I brown some meat for tacos.

He’s my favorite until he mentions casually over dinner that I might have thought he was doing homework in his room after school but what he was really doing was drawing his new comic book and he’ll have to do his homework tomorrow morning (which will never happen. He and I both know this.).

When I was a kid, I was convinced that my mother had a favorite child. Now I understand that her favorite was always changing. Each one of my children can be my favorite in these snapshots of time when they do something or say something unexpectedly sweet or when they follow instructions to the letter or do what was asked without arguing or sassing.

Parents do have favorites. It’s just that the favorite is always changing, constantly rotating through the inventory.

Except the baby, of course. He’ll always be my favorite. At least until he hits age 3.

This is an excerpt from This Life With Boys, the third book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography)