by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

We walk into the school, turning the corner down toward his classroom, and I can feel the tension and sadness pulsing through his hand in mine. When I turn to him for this morning goodbye, his pupils are so large his eyes look nearly black.

By this time next week, my boy will be in a new classroom, with a new teacher, with new anxieties sitting on his chest.

Today, he will walk into his old classroom, after three days in school suspension for a mistake he made that was sorely misinterpreted, and he will sit at his old desk and he will look around at those old classmates he’s shared a room with for two years, and he will know that it is his last day here, with a teacher he loved but who no longer has the patience and stamina to handle his emotional outbursts.

This morning I can’t even make it all the way to his door because of the emotions clogging my throat, pulling tears from their unending reservoir down my cheeks, so I stop, two rooms away. The only person I see in this crowded hallway is my son, trying to breathe, trying to be brave, trying to overcome all this rejection and misunderstanding and a label that, already, sticks hard to his seven-year-old back.

I try not to let him see my tears, brushing them away quickly like I did this morning, when he showed me the note he’d written to his teacher—a picture of her in a classroom and him sitting at a desk, crying, and a thick wall between them, underlined by a few words: I will miss you.

But he feels their water trail when I bend over him and press my face to his and whisper the same words I’ve whispered in his ear every morning before dropping him off: Remember who you are. Strong. Kind. Courageous. And most of all my son.

And then I watch him walk through that classroom door for the last time, not sure how this day will go after the last sixteen.

Will he remember who he is, or will he remember who they say he is?

They are two very different things.

///

Four days ago I sat in an office with the school principal and her assistant principal to talk about the latest of my son’s conduct violations, misinterpreted from my perspective. But it joins fifteen other conduct violations—for tearing up his already-graded homework when he felt angry, signing his name as “stupid jerk” when he felt sad, and collapsing into a crying pile on the floor when he didn’t get to use the magnifying glass for his science project like everyone else in the class did—in the last twenty days. They are telling me something must be done because his classmates are afraid of him and his teacher doesn’t think she’s a good fit for him anymore and all of it is against the school’s code of conduct.

This boy has always been our spirited child, and his daddy and I have worked diligently over the years to give him the tools and space and practice to handle his big emotions, but there are days and whole weeks sometimes when those big emotions grip him and refuse to let go.

I try to tell them what we’ve learned from each of the write-up incidents, at least the four of them we’ve seen. The story, from his perspective, tells much more than those words written on a discipline violation page, but how do you argue with a school administration that sees only the bad behavior and not the boy behind them?

This last incident, the worst of them, happened when it was leaving time. He was finishing up an art project, his favorite kind of project, trying to cut out his picture before he needed to pack up. The substitute teacher, probably frustrated by his lack of obedience, tried to grab the scissors away from him, but he beat her to it, throwing them into a corner of the room. Fortunately, no classmates happened to be in this corner because they were all packing up their backpacks like they were supposed to be doing, a disaster averted. But then he ran out of the room to escape the fire of his own anger.

The sub, who had been “warned confidentially” about him, did not talk to my son about his outburst but, instead, wrote up a conduct report of her own observations and assumptions. She never considered why he might have felt the way he did or why he chose to express himself that way or what emotion might have caused a little boy to run away.

And it’s not okay—of course it’s not. Children shouldn’t throw scissors, even if they’re blunt-tipped, anywhere near other children. Children shouldn’t run from a room where a teacher is charged with keeping students safe. But kids, I believe (and psychology has begun to prove), always have a reason for what they do, and the reason is often buried so far down it has to be dragged out with skillful fingers.

Sometimes the meltdown can be prevented in the first place by a word or two about how hard it is to put down an art project when there are no minutes left for working, instead of grabbing scissors from the hands of a focused boy. It’s always worth a try.

The administrators, in the meeting, said they wanted him to stay in school suspension for three days for this latest incident, so he’ll “learn his lesson this time.” And I can’t help but wonder what this lesson is that we’re trying to teach. He is seven years old. At the depths of his heart, he doesn’t want to mishandle his emotions or scare people or spend a whole day or three of them in isolation from all the people he loves.

He slumped against me when I broke the news that he would not be returning to class just yet. He didn’t understand. I tried to help him understand.

“Your substitute teacher thought you were threatening her,” I explained.

“But I wasn’t,” he said, his eyes filling with tears.

“I think she might have misinterpreted what you were trying to do,” I said.

“She thinks I’m bad,” he said, and then I was blinking tears away.

I read the despair in his eyes that day, and I could physically feel the giving up, the hopelessness waiting around the corner. How does a kid who’s led to believe he’s the “bad kid” ever become anything but a bad kid?

The question stood between me and school administrators that day.

So I pulled him tight against me, and I held him through the words he sobbed: I just don’t understand why they don’t believe me. I didn’t do what the substitute says I did. And then I held him through all the minutes after, when big emotions shook his body quiet.

I told him that sometimes what we intend to say with our words and actions and what others interpret are two very different things, and we have to be careful about how we come across. I don’t even know if he understands this communication nuance, because he’s seven years old. And then the bell rang and it was time to leave, and his little brothers were still waiting patiently for the walk home.

But before I left, I whispered words I hoped would stay with him all day in the quiet of an isolation room: You are loved deeply. Remember who you are. You are not these mistakes, ever.

It hurt my heart to leave him in that room all by himself, but I did.

I cried all the way home.

///

Once upon a time, when I was a senior in college, I substituted for a “troubled” school district near my university. Every time I took a job, there were students the teacher warned me about. And all day long I would wait for the trouble.

It would always come.

I was quick to write up those conduct violation sheets, because I had been warned it would probably happen, and I’d been shown where they were kept, and I’d been directed how exactly to fill them out.

I know now that those problems probably came because the kids knew I was watching, since someone was always watching. They knew I was waiting, because someone was always waiting. They knew that whatever they did they wouldn’t be able to win—my word against theirs, no matter their intent.

When you believe a kid is a problem, all you’ll ever see is the problem.

I wish I could go back to all those kids I sent to the office with a condemnation sheet in their hands. I wish I could tell them, You are more than this problem they warned me about. I believe you can do better. And I am not waiting for you to fail. I am waiting for an opportunity to help you succeed.

I feel sad that my young son is that kid, but being on this side of it helps me to see that they weren’t just “problem kids” like we teachers were trained to believe. They are not problems to be solved. They are little precious people crying out for help because of emotions and circumstances too big for them to understand and talk about.

That doesn’t mean that what they do to communicate their plea for help is right. But it does mean that we, the adults, have a responsibility: to become a child and see from their perspective and always assume good intent, because sometimes what we see a child doing and what they think they’re doing are not the same thing.

I wish I had known this back then. I wonder how it might have changed the lives of those “problem” kids.

///

My boy has been through a lot in his short seven-year life.

There was a sister-death when he was four. There was a twin pregnancy, a few months later, when a mama was in and out of hospitals and doctors’ offices because we thought we’d lost them and we hadn’t and we thought we’d lost them again and we hadn’t, and then they were finally here, and they spent twenty days in the neonatal intensive care unit, and a mama and daddy left boys with a rotating babysitter every night so we could spend two hours with the tiny babies who needed us in that short window of time. And then those twins came home, and I don’t think any of us even remember the whole first year of the twins’ life, because everything blurred into chaotic oblivion.

In the middle of that chaotic year he started school. It was a brand new environment not so different from home in terms of noise and bodies, but also widely different because there were twenty-four other students a boy could get lost behind. My best guess is it was overwhelming, overstimulating, and, perhaps, somewhat unbearable for a boy who valued working on his own in a quiet space.

His actions said what he could not say: Help me. Help me process what I’m feeling. Help me feel understood. Help me know what to do with these overwhelming emotions. And no one in those classes would listen, because they were there to learn, not to heal, and a boy, five years old, built up his armor so efficiently nothing could penetrate it.

Which brings us here, to a place where a boy’s armor is starting to crack. This boy doesn’t know how to deal with those pieces he’s hidden for so long, pieces that are leaking out faster than he can patch the hole.

This is the reality that isn’t shown on a conduct violation sheet.

When I started my parenting journey, I never thought I would be the parent of a child who had trouble in school, a child who is brilliant beyond his age and gets all the right grades, a child who is a minefield of emotions.

I probably should have.

I was a kid who preferred a room of five or six to a room of twenty-four. I was a teenager who preferred staying home to read Wuthering Heights and Pride and Prejudice and Doctor Zhivago out back in the hammock, rather than going out with friends. I am still the woman who waits in the school pickup line with my heart pounding, hoping no one will look me in the eye, because then I might have to talk, and I hate small talk.

I often wonder how I, a big emotion, highly sensitive introvert, would have fared in today’s classroom of pods and constant group activities and no real space of my own. It’s no wonder my boy, walking around with a fever of frustration, wondering where he really belongs, over-stimulated on an hourly basis, is crying so loudly for help.

And when a child cries for help, we must listen first and “fix” later.

Sometimes there are ways to bully a boy that have nothing to do with fists and words and threats that scare him into cooperation. Sometimes there are lonely lunch tables and sitting out the fifteen minutes of recess he needs and isolating him in an office for three days. Sometimes bullying can look like kids tattling five times a day on the one boy they’ve learned will always get in trouble, the one teachers will always believe did something wrong. Sometimes bullying can look like writing up a boy sixteen times in twenty days without asking the question, “Why is this happening?”

No kid is born a bad kid.

And if all we’re doing is writing up a kid for a behavior violation, and we’re not doing the work to find out why that behavior violation might have happened, we all lose.

///

Last night my boy sat in his bed while his daddy and I tucked him in. It was there we told him he’d be changing classrooms. His first words were, What if I’m sent to the office again?

And then he cried and begged not to go to school anymore. He is seven years old, for God’s sake.

He is seven years old, and in his mind, everything he does anymore means he’ll get told on by another student. Every action he chooses is the wrong one. Everything about him is unacceptable. His eyes tell me this. I can hardly bear it.

How does a parent speak truth into a heart that believes he’s a problem, an inconvenience, a “bad kid” who will never learn to control his impulses because this is what all those discipline write-ups in a twenty-day history tell him, and this is what a teacher not wanting him anymore tells him, and this is what an in-school suspension sentence tells him.

How do you convince a child that he is loved, that he is good, that he is more than his seven-year-old mistakes, when those conduct violation sheets tell him a different story?

The question follows me into sleep.

And there is a dream, like there has often been on nights I needed to know something—when I saw my brother’s overturned vehicle in a dream before his car accident, when I dreamed of waves too high and dangerous and begged him not to go on his deep-sea fishing trip, when I saw my third son lying in a baby swing with his head wrapped in a bandage weeks before that head injury happened in a church nursery.

This one is no less clear.

In it, we were walking down his school hallway, and in the flash of a moment, I had his new baby brother, Asher, in my arms. He was minutes old. I sat down with my oldest boy at the door of his classroom, and he was very gentle and sweet. He leaned down to kiss Asher and said his brother’s name once.

Then he sat back against the brick wall, and his face got red, and his eyes filled with pain and tears, and he said his newest brother’s name again. “Asher,” he said, except this time his voice filled with sadness and despair. I knew what to do in my dream. I put Asher down in the middle of the hallway, and I took my biggest one in my arms instead. I held him for as long as he sobbed, which was a long, long time.

I woke to an answer that felt clear and awful, all at the same time.

My son has lost his significance in his family at home and his “family” at school, and he is asking for help the only way he knows how. The last three years of his life he has only ever known one brother after another encroaching on his world, and now there will be another. Who is he in the six of them? Who is he in the twenty-four others at school? When will someone listen to hear him? When will someone care enough about his emotional state to help?

Behind all those discipline write-ups, beneath all those words scrawled on a behavior violation page, this is the story told. This is the armor that has begun to crack, because a seven-year-old can only self-repair for so long.

So we are peeling the rest of that armor away. We are rolling away the stone from this grave that sits in the corner of a little boy’s heart. We are fighting, in all the ways we can, for a child who is significant and beautiful and precious, no matter the mistakes he has made in the last thirty days.

We are unwrapping the grave clothes. We are whispering truth. We are writing his name on the tablet of his heart: Gift.

Because this is who he is, even if a school system has flagged him as something else entirely. Still we hold him as a gift.

And there is Another who holds him and fights for him, too. There is Another who will speak his true name and burn up that false one stamped on his back by a world that doesn’t understand. There is Another who promised victory.

And so we wait and hope and love in all the spaces we can.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by This is Now Photography)

by Rachel Toalson | Books, This Writer Life

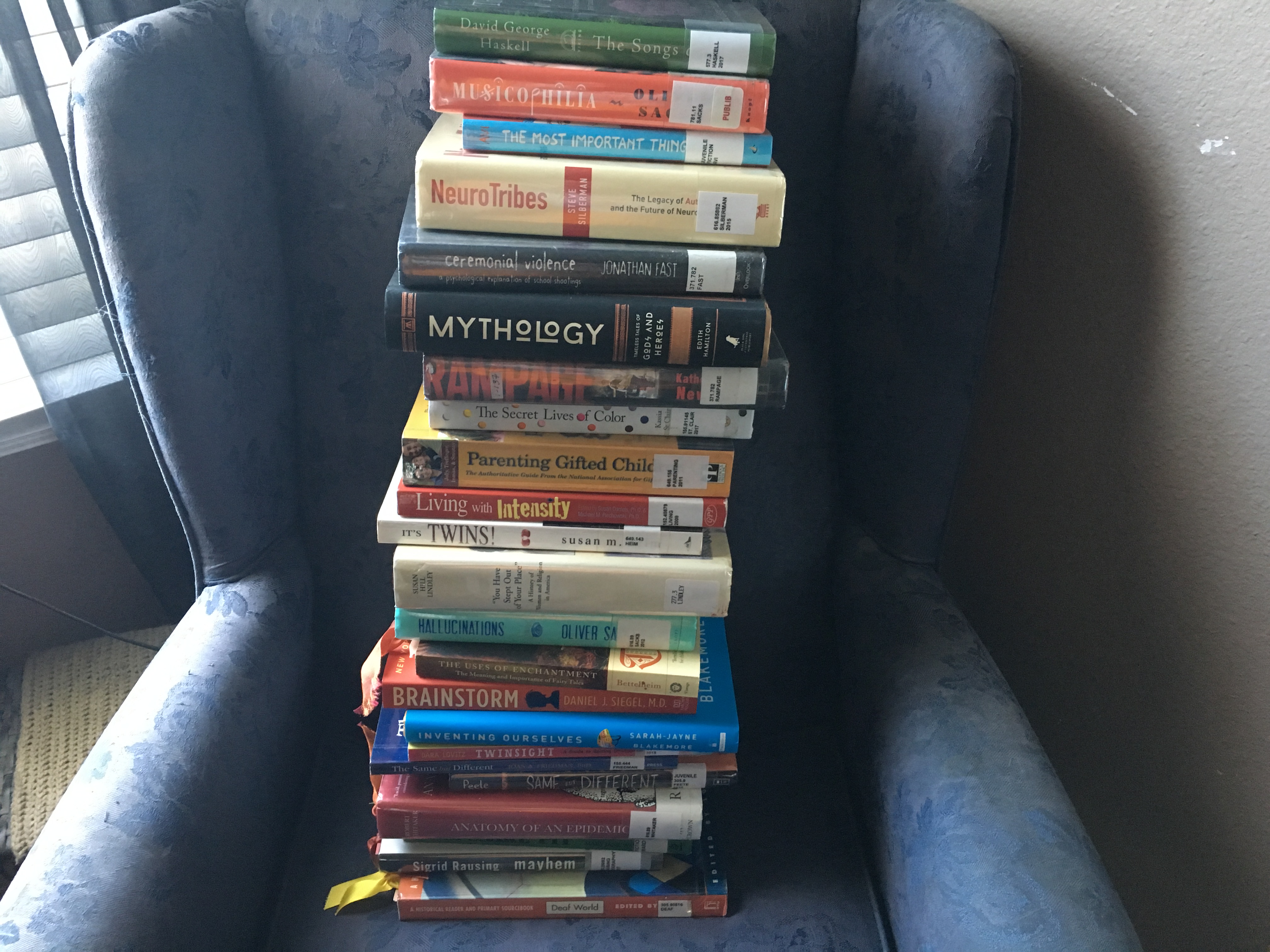

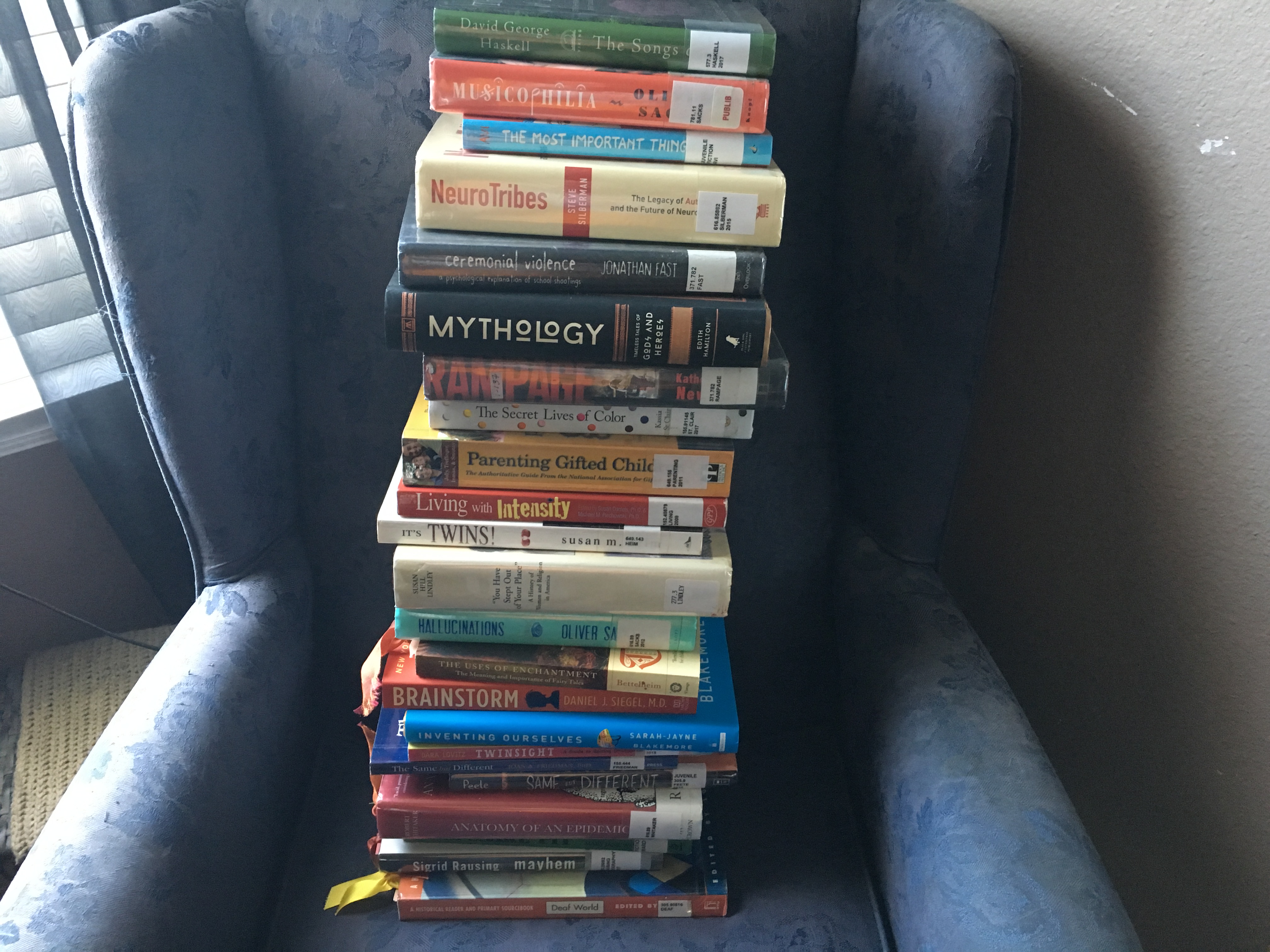

I once heard a writer say that she could usually finish all the research she needed to do for a story in about a week.

Meanwhile, this was my research stack for the summer.

It could be because I’m a former journalist, but one of the biggest challenges for me is knowing when to quit research.

It might seem strange to think about a fiction book needing so much research, but part of our responsibility (or so I believe) as writers is making sure that whatever we’re trying to portray—whether it’s a character who’s a twin (and don’t ever assume that just because you’re the parent of twins, like I am, that you completely understand the neurological and psychological characteristics of twins; I’ve learned so much from my research, which has, fortunately, also informed my parenting), or a place that’s becoming swallowed up by gentrification or a character who’s obsessed with trees—is portrayed accurately within the scope of our story.

The first thing I do during my research stage is put a bunch of books on hold at my local library. Usually all the holds come up at once and then I have to decide which books I’ll read first. Some of the books are more helpful than others for what I’m specifically trying to do, but I like to read as many of them as I can; I don’t think you can ever do too much research (unless, of course, it’s your excuse to avoid writing).

My second wave of research is interviewing people who have lived the lives I’m trying to portray. For example, I currently have on submission a young adult novel about suicide and depression. Even though I’ve experienced both of these things in my life (I was never suicidal, but someone very close to me was), I wanted to reach out and talk to more suicide survivors and their parents to record their experiences. Even if I don’t use any of what I’ve collected from these brave, resilient, remarkable teenagers, the more information I have, the more it helps me better portray whatever issue I’ve chosen in a story.

Which is much better than relying on stereotypes.

So take your time researching. You never know what you’ll find or just how much it will improve your story.

(Photo by All Bong on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

What is this that

wakes me from sleep

when little ones lie

peacefully across the hall?

An idea, singular,

a snippet, a thread,

and as I rise, shaking off the covers,

it is gone like the years.

Here they come to

knock and pile and kick and twist

and the losing, the tearing away,

settles into a brow

So that even when food is given,

smiles are shared, love lifts

the top of a wooden table,

it is there, a great hole of nothing

Nagging, stealing, splashing light with gray,

turning a head from what is before

and around and all in between

so the happy day smudges at the edges.

It is work and pain

and pleasure and despair,

love and hate,

a relentless torture, this art.

And yet

it is life for

the ones it calls

who dare to dance.

This is an excerpt from Textbook of an Ordinary Life: poems. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

I’ve decided to eat healthy again.

We’ve just had a long week and weekend of rewarding ourselves for getting through the day. It was more than that, actually. It’s incredibly counter-productive to have a birthday at the end of January, right during the time you’ve hit your stride with healthier living. You start off the new year on fantastic footing, getting your eating under control after the holidays, and then you’re bombarded with a birthday and the irresistible temptation to relax your food rules a little—take a day or maybe two days or maybe the whole week.

You can see how this quickly becomes a snowball.

I don’t know why I haven’t thought of it before, but this yearly struggle could likely be alleviated by starting my new year in February. And pretending Valentine’s Day doesn’t exist.

So here we are, a week past my birthday. I’m ready. Let’s do this.

No sugar for the next thirty days. A cleanse. My favorite thing to do.

Sunday night

I’ll start tomorrow. Tonight I’ll eat an entire container of Ben & Jerry’s delectable ice cream in my favorite flavor: “The Tonight Dough.”

Monday early early morning

The day unfolds like it’s stacked against me: with (surprise and oh, joy!) my monthly visitor. But I am strong. I can do this.

Monday early morning

Workout’s finished, it’s time to get the boys up for school. I can totally do this. Totally.

We race out the door, to walk the school boys to their elementary school three blocks down the road. My four-year-old twins don’t wait to cross the street, because they think, erroneously, that they’re competent at everything. They almost get run over. Now they have to hold on to the stroller, so they’re both wailing. One is refusing to move forward, so he gets to be carried. He weighs a lot. I already did my workout for the day, and now here’s another.

I deserve a reward. I resist.

We’re home. I let the twins race for the front door. They get there before me, which means they have an opportunity to do something real quick before I push inside with the stroller carrying their baby brother. The something they do is grab the markers their second-oldest brother left out this morning and color the piece of art he was drawing for me, which he was planning to finish after he got home from school. When I walk in, the one doing the coloring, which he should know, by now, he’s not supposed to be doing, after countless lectures about coloring on other people’s art, says, “My brother left this for me to color.” The picture is ruined, and not just a little bit. I send them outside to play.

I deserve a reward. I resist.

While they’re outside and I’m wrestling laundry out of the washer and into the dryer, the baby silently climbs the stairs and starts sticking his hand in the toilet, because this is one of the funnest entertainment ploys of all time—especially when it hasn’t been flushed, which is the terribly frequent state of most toilets in my house. I discover him, along with the mess he’s made, while I’m carrying clean clothes up the stairs, so I set to work cleaning. The twins peer in from outside and see that I’m not in the kitchen or anywhere they can see, because, to reiterate, I’m upstairs trying to wash the poop water off their baby brother’s hands. The two of them decide this would make the perfect opportunity to steal inside the house, rummage through the cabinets, and pour all the homemade cleaners into a gigantic hole they and their brothers have been digging in the backyard. That’s not enough, though. While I am still preoccupied with their brother and his disaster, they break into Husband’s shed and find a gasoline can.

A quick aside: This has happened before. There were consequences. They don’t care about the consequences. They break inside anyway.

Out comes the gasoline can, which they also pour into the gigantic hole. Husband was planning to use that gasoline to mow our lawn later today, because we got a note from our homeowner’s association saying it was a little out of hand. Also, there’s a shrub that needs trimming, the letter said. It didn’t say which one of the eight in our yard they believe needs trimming, so we’re just guessing. Unfortunately, it’s not the one the twins, after dumping all the cleaners and gasoline into this hole, decided to cut with the shears.

They are herded inside and told to sit on the bench at the kitchen table. They smell like pickled gas pumps.

I need a reward. I barely resist.

Monday lunch

The only time my sons are still and quiet is when they have food in front of their faces—and barely then.

After lunch, I wrestle them into bed, for a few hours of blissful nap time when I pretend I can’t hear the twins jumping off their bed and having a good old time before they crash in various chalk crime-scene positions on their floor or bed or wherever it is they collapse in utter exhaustion.

I don’t need a reward. I can do this.

Monday afternoon

Fighting, shrieking, complaining about homework, someone says he hates me, someone else says he wishes he had different parents, especially a different mom, like I can’t hear him, someone forgets to flush the toilet after a very loud unloading session on said toilet, making the whole downstairs smell like a sewage plant, someone else eats five apples without permission (which means he’ll probably need the toilet soon).

Why are kids so hard?

I need a reward. I…resist.

Monday dinner

They’re all complaining about dinner, and I am, too.

Why can’t we have pizza? they say.

I don’t know. I really don’t know anymore. Why are we doing this to ourselves? Why are we torturing ourselves and our children trying to eat the food that is good for us but takes twice as long to cook and four times as long to complain about and tastes like…

Oh. It tastes pretty delightful.

(So would cookies.)

I deserve a reward for cooking this amazing dinner.

No! I’ve made it all day!

Must…press…on.

Monday bedtime

After stories and brushing teeth (during which time someone lands a glob of spit and mint toothpaste in the middle of the mirror I just cleaned), we wrestle them into bed. Three times.

We have to visit the twins’ room four times, and the last time we enter, they’ve changed their clothes.

“Why did you change clothes?” I say.

“Because we accidentally peed,” one says.

I look around. The floor is clean.

“Where did you put your clothes?” I say.

“Under there,” the other says. He points under his baby brother’s crib, where, when I bend down to look under it, I see a whole wad of clothes. I gag. It smells like a horse pasture under here. I don’t think I even want to know.

I leave.

“Get back in bed,” I say to the older boys as I pass through.

And just when we think they’ve finally settled down and are actually going to sleep, one of them bursts into the room and tells us he accidentally brought all his drawing supplies up to the library and one of his brothers stepped on a drawing pencil and broke it and now he’s really, really sad.

I deserve the biggest reward.

I want to resist, but…

Monday before sleep

I’ll start the thirty days tomorrow.

It’s all good. I got this.

This is going to be easy.

This is an excerpt from Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On, the fourth book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Jez Timms on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

They were rowdy, loud, and I hadn’t quite gotten enough sleep last night. The noises were grating on me: some kids shrieking (at least it was in happiness, or something close to it), another kid tapping the table with a spoon (a soundtrack rhythm of annoying proportions), and one more kid racing a scooter through the kitchen (adding to the shrieks), while I tried to put together a smoothie for breakfast.

I poured the yogurt, shook out strawberries, added a few frozen bananas and switched on the blender, enjoying the familiar hum that almost drowned out the sounds of my children. I closed my eyes, trying not to count how many summer days remained, trying to breathe and grasp at a flimsy, slippery hope, trying not to admit that this—this intolerable, madness-filled morning—was the last straw of summer vacation.

I shut off the blender. Turned toward the glasses, lined up. Started to pour.

Someone screeched.

“This is the last straw.”

Had I said the words aloud?

I looked up. My oldest son was staring at me, his brown eyes wide. He repeated himself. “This is the last straw.” He held out a mason jar, one stainless steel straw scraping along its lip.

“Where are the other straws?” he said.

I couldn’t answer. I could only laugh.

He stared at me for a minute, then bent and opened the dishwasher, where other straws gathered in one rectangular tray. He stuck them in the cups after I filled them.

I thanked him for his help—a bright spot in an otherwise trying span of moments.

(Photo by Philip Veater on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

I miss her laugh the most,

the way it would shake itself

out into nothingness,

like all the air had gone

and she could find no more,

but it was a happy place to be.

Sometimes she would get so tickled

my uncle had to slam his hand

against her back to get her

breathing again, but that

made her laugh all the more.

I miss those late nights

I’d spend reading in my room,

during the few summers

I lived with her.

I would make my way

into the bathroom for my

nightly routine of washing a face

and brushing my teeth,

and the dining room light

would still be blazing,

and there she’d sit at the table

in purple slippers with a

crossword puzzle open

in front of her. She’d be

chewing on the end of a pencil,

oblivious to the stacks of papers

shoved in corners. She’d have a

bag of potato chips or Riesen caramels

open and ready at her elbow.

I miss her purple lipstick

that always left traces on her teeth

and the way I would watch her

leave for work at the school

down the road while I

got ready for my own job across town.

She’d always remind me

to lock the door on my way out

and be sure to unplug

the curling iron.

I didn’t use a curling iron,

but I never told her that.

I miss seeing her slumped

on the couch in the middle

of the ten o’clock news, which she

insisted on watching every night,

and I miss the feel of her hand

on mine whenever she was near me.

I miss her curly black-white hair,

and I miss those eyes that never

seemed to miss a thing and the

handwriting in all caps and the

old Agatha Christie volumes

that sat on her shelves,

battered from excessive re-reading.

I miss the way she might have

looked at my sons and the

laughter that might have

shaken itself out into silence

at every humor piece

I carefully crafted with

her in mind.

She might not have lived

a remarkably extraordinary life,

just one that was

remarkably ordinary.

But in my memory,

she is a giant.

This is an excerpt from Textbook of an Ordinary Life: poems. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

When you’re a parent of irrational children (which is every child for at least a small amount of time), there are a whole lot of hills. There are hills where you will battle over which color plate is the best color plate, even if it’s a color that doesn’t exist among the plates stacked in your cabinet. You will battle over whether or not a plate of that color, indeed, exists inside your cabinet. You will battle over why the orange plate is the plate they’re getting if they want lunch.

There are hills where kids stand with feet planted and arms crossed and say they’re not going to wear the red shirt because their teacher’s favorite color is blue, and they want to make their teacher happy today, not you. There are battles where kids insist they put their shoes where they’re supposed to go yesterday and someone else must have moved them. There are battles during which kids will pick their nose and eat the treasure right in front of your face while claiming they don’t pick their nose and eat the treasure anymore (I just saw you. Nuh-uh!).

There are massive hills and tiny hills, round hills and oval hills, rock-solid hills and mushy ones.

One thing remains the same: There are many, many hills.

These hills can get bloody and complicated, depending on the battle. But one thing I’ve learned in my parenting life is that if we’re engaging in full-armored and weaponed battle on every single hill our children summon from the rocky ground of childhood, we’re going to die on every single one of them.

So there are some hills I’m no longer willing to die on.

1. The Hill of What They Look Like

I don’t care if they wear a vertically-striped shirt with shorts that have horizontal stripes. I don’t care if the waistband of their pants is pulled all the way up to their shoulders. I don’t care if they could walk the Pacific Ocean without getting the legs of their jeans wet because they’re wearing their twelve-month-old brother’s jeans.

I don’t care if they didn’t brush their hair today, because they’re boys, and their hair’s short. Knotted, but short. I don’t care if they’re saving that smudge of jam on the side of their face for later. I don’t care if they wear one flip flop and one tennis shoe all the way to the library and back. I don’t even care if they wear two left shoes, so long as the decision was theirs and they don’t complain about it.

I don’t care if this shirt is as wrinkled as their eighty-year-old great-grandfather’s face because they like stuffing their clothes in drawers instead of hanging them up. I don’t care if they buttoned up their shirt all wrong and they flail away from me every time I try to fix it.

Whatever, kid. Have your way with that wardrobe. Come back to see me when you start caring about impressing girls.

2. The Hill of Where Or When They Tantrum

I used to be super-sensitive about this. When my first son was born, I was conscious of every place, every person, every escape route my kids could take to run far away from the meanest mom ever.

If we were in the doctor’s office, my son couldn’t tantrum on the way back to see the doctor, whom he remembered as “the man with the woman carrying a needle,” because it would disturb all the other people. If I were in the park, he couldn’t melt down by the swing sets without great and near-fatal embarrassment on the part of his mother. If we were at his school, I could feel the eyes of the teachers and all the other parents upon me, and I’d consider, at great length, what it might look like—what it might say about me, as a parent—if my kid dropped to the floor and started [panic attack] kicking the ground.

Well, I don’t care anymore. I’ve become conditioned to the tantrums, I guess.

I don’t care if my kid throws himself across the mulch of the park’s ground and shouts about how I’m the worst mother in the history of the world’s mothers because I won’t let him go one more time across the monkey bars even though it was time to leave five minutes ago and he’s already drained his buffer time. I don’t care about the stares I get from the other watching people, likely (or maybe not) condemning me for the way my kids are behaving, as if their behavior somehow reflects on how good or bad my parenting skills are.

If my kid’s acting the fool, I’ll let him act the fool (within reason, of course), because the consequences of acting the fool that will come later, when we’re away from all these people, will carry a lesson in its sit-on-the-couch-and-let’s-have-a-talk.

3. The Hill of They Just Broke Something

I used to be fond of things. Now I’m more fond of people.

So I don’t care if my kids accidentally break something that doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things, because those sorts of things—a lamp that is knocked over by a stuffed animal someone was really excited to find; a sconce that shattered when someone thought it would be a good idea to sword fight with brooms; a wooden chair knocked over in a game of chase conducted inside the house on a rainy day—can be replaced. What can’t be replaced is a relationship lost or damaged over something as silly as an unexpected breakage.

The really important things (pictures that mean a lot, computers, valuable books) are put away where kids can’t get them, and all the rest of our “things” are fair game. My fault for having them out.

This also goes for spilling, destroying, or losing things.

4. The Hill of My Kid Just Said Something Inappropriate or Embarrassing

Kids are really good at embarrassing their parents. They’re good at saying words the wrong way or saying things without thinking them through. In fact, some of the things they say, they don’t even have the capacity to think through.

There is a story of three-year-old me that has been told and retold in our family folklore. The story goes that when a woman my mother knew told me I was the cutest little girl she’d ever seen and, after this compliment, asked me if I wanted to go home with her, I looked at her and said, “No. You’re too fat.”

I was not a rude child. I was simply way too candid.

I would be mortified if one of my children said this today. My mom apologized profusely and later talked to me about the difference between truth and keep-it-to-yourself.

My kids have had The Talk. It apparently hasn’t sunk in yet.

Don’t ask them what color your teeth are or how old you look today or whether you look a little…chubby…in this dress. They will answer gray, four hundred twenty-three, and very much so. (This is hypothetical; I don’t wear dresses.)

I no longer care about their embarrassing displays of honesty.

Yes, Mama forgot to put peanut butter on the sandwiches yesterday so all you had in your lunches was bread; go ahead and tell your teacher. Yes, Mama’s legs are really hairy; how ‘bout you announce it to the world, and then I can actually wear shorts outside the house unashamed. Yes, Daddy dances like a chicken in pain; be sure to tell all your friends so they ask to see the chicken-in-pain in action next time they come over.

5. The Hill of I Must Keep a Perfectly Tidy House

I saved this one for last because it has been the hardest one for me to surrender. I’ve died on this hill a thousand times, sometimes daily. But no longer. I will not die on this hill.

Kids come with mess. They’re really unskilled at cleanup, no matter how many times we train them to do it well and efficiently. And of course we’ll keep trying. But if I continue to die on this hill of I Must Keep a Perfectly Tidy House, I’m either going to sacrifice my best relationship with my kids or I’m just going to become one of those mothers who walks around talking to herself (oh, wait. I already do that.). A mother who is dissatisfied with the whole of her life. I don’t want to be that mother.

So [deep breath] I don’t care if he leaves his sock right next to the dirty clothes hamper. We’ll have our cleanup time at the end of the day, and he’ll do what needs to be done. I don’t care if he takes out a sheet of art paper and then, in his concentrated state, loses count of how many pages he got out, and now the table looks like it’s made of papier-mâché because (of course) he also spilled the glue. I don’t care if he cuts up his worksheet from school into tiny little confetti pieces. He knows how to vacuum, and it’s almost time for the motivating force of Allowance Handout.

If we’re fighting every single little battle that comes our way, we’re not going to win the war. We don’t have enough stamina. We’ll burn out halfway to the end.

So these are hills I’m not willing to die on. What are yours?

This is an excerpt from Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On, the fourth book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

This weekend my husband and I sifted through fifteen years of papers and pictures we had stashed in boxes in our garage. We found college essays, old emails we’d sent to each other, and baby pictures of us that our parents had handed over years ago.

In among the pictures, I found one that captured five generations of the women in my family.

I remembered this picture. It used to make me laugh when I was a girl, because the older the generation, the shorter the woman. I was around eleven or twelve in the picture; I was the tallest female standing.

What I noticed this time, however, was not only the stair step quality about that picture; I noticed the women—their strength, their poise, their certainty that life was theirs for the taking.

There was white-haired Memama, who lost her husband young, who lived, alone, in the house he built her until the day she fell on its sidewalk and died during hip surgery, who slept with a pistol under her pillow, just in case. She was legendary in our family. She lived until she was one hundred years and two weeks old.

There was her daughter, my Nana, who had false teeth and a pacemaker, who wouldn’t go anywhere without her orange-tinted lipstick, who made the best chicken and dumplings in the south. She lost a son early, in a car accident, practically raised his kids, lost her husband in his garden, and drove way too fast, as though daring life to take her, too. She would have loved to know the Astros won the World Series this year. She lived until she was ninety.

There was her daughter, my Memaw, who had a fiery temper (especially on roadways), loved the color purple, and stayed up late snacking on Riesen caramels, potato chips, and Werther’s original hard candies. She was opinionated (just ask my Uncle John), bitter at the edges, and one of the most generous people I’ve ever known. She lived without her husband for more than thirty years, in a house all by herself, until she died at seventy-four.

And there is my mom, who spent years raising her three kids as a single mom before my stepdad came along. She made hard choices, worked more than one job, and sacrificed her dream of becoming an anthropologist to become a school librarian (which I think she liked better anyway). Today she runs the Jackson County library I grew up visiting and stocks every book I write.

Sometimes I forget this long line of strong women who stand behind me. I forget that they are in my bones, in my veins, in my mind and heart. I forget that their strength is also my strength, that the greatness that lived in them is also the greatness living in me.

Looking at this picture makes me wish that the three women in it who are no longer living were here—to walk, unafraid, out the doors of her old house on the wrong side of the tracks; to yell raucously for the Astros and remind us that she’d been rooting for the right team all along; to laugh until the sound shakes itself out. To meet my sons, to show them what strong women look like, to share a past that is wholly unimaginable to children today.

But the ones who remain—my mother, my aunt, my sister, and me—will tell their stories, live in their strength, and carry on.

We will remember.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

It is not outside the realm of possibility that other homes with children can exist without as many rules as mine. But, unfortunately, it is also not outside the realm of possibility that my home would devolve into a scene from Lord of the Flies if it were not governed with rules. Left to their own devices, boys would pull dirty socks from the laundry and wear them every day, never take a bath, and likely accidentally die by daring.

We have rules for everything—rules I never thought I’d have to make. But that’s a subject for another day.

What I want to talk about today is how running a house with rules does one particular thing better than all the other things: It highlights the amazing strong will of the family’s non-conformer.

I have a few of these non-conformers in my house, and you’ll see them out and about with shirts that are not buttoned up correctly (Me, to my four-year-old twins: What is taking you so long to get dressed this morning? Both of them, in unison: We’re wearing button shirts and we’re buttoning them ourselves. Hey, more power to them.), shoes that likely don’t match, and, secretly (or not so secretly, if you’re the four-year-olds), no underwear.

There is one who is more…let’s call him intense…than the rest.

It’s not easy raising a non-conformer. Sometimes it’s the most annoying thing in the world.

I’ve never been the sort of parent who expects my kids to be perfectly behaved all the time. I also have never expected my kids to be exactly the same. I know kids well enough to understand that (a) they have bad days and (b) they’re all different. Maybe that makes parenting a little more challenging for me, but it also makes it more enjoyable. I get to see my kids blossom into who they are.

I have another problem as well: I’m a non-conformer. I’m the kind of person who, when someone tells me I can’t do something (I’m not speaking of crimes and such; don’t misunderstand me), my response is, “Watch me.” I want my kids to have that same attitude—not convinced by the “experts” who say they know everything about everything.

It’s just that when it comes to a nine-year-old non-conformer, things get a little tricky. Sometimes, honestly, I’d rather he just give it up and conform already. It would be easier for me.

My non-conformer walks to the beat of his own drum. He has a billion ideas in his head and a maddening urge to do them all, right now. He talks nonstop about the plans he has, the benefits of letting kids build with LEGO pieces all day every day, and Minecraft.

The most frequent word ejected from his mouth is “Why?” As a question. Sometimes as a response. All the times as a challenge to authority.

Here are some of the things we go round and round about.

Dress code

We don’t ask much. At school, we just want our sons to be comfortable—which means no shorts in the dead of winter and no sweat suits in the dead of summer, which is pretty much every month but January and February here in South Texas. Other than that we only expect tennis shoes, socks with the tennis shoes (you’d be surprised how many times they forget socks, which is why my house smells like an ancient Frito factory mixed with soured sweat when I’m not proactively diffusing essential oils), and a shirt of any kind. (We’ve had to add a couple of amendments to this, including (1) no shirts with nipple holes you cut out with scissors and (2) underwear. Please, underwear.)

The non-conformer slides around this dress code by not tying his tennis shoes. I told him the other day that he should just take the laces out and save himself some trouble. He said, “Why?” which is the standard response any time we say anything that has the word “should” in it. I’m waiting for him to trip and bust his face (not too badly, of course), so I can say, “That’s why.” In a very empathetic and understanding tone, of course.

Church is a bit of a different story. We still don’t expect much—we want them to wear jeans and a T-shirt or a nice shirt, if they so desire (they hardly ever desire). No holes in jeans, no sweat pants, no ratty clothes that make you look like a feral cat that got in a nasty fight.

The non-conformer is the kid who’s dressed in sharp black dress pants and shoes that are actually tied for once and yet dons a collared workout shirt.

It’s about all we can ask.

Homework

We want them to do it. Before tech time, before play time (as much as that pains me), before dinner time.

The non-conformer will fight, cry, argue, stomp for half an hour, then begrudgingly take five minutes to do his homework, because he’s a whiz at all things academic. Yesterday I tried to point out that if he just sat down as soon as he got home and did it, he would have so much more time for other things.

He said, “Why?”

I shook my head.

Dinner

Everyone in our house is expected to be at the dinner table promptly after we call them. The key word is “promptly.”

We will call everyone into the house, and most of my boys will be ravenously eyeing the food they just said they didn’t like before they’ve tasted it, and there is one seat empty. Guess whose.

We’ll go ahead and pray without him and dig in. He’ll amble to the table five or ten minutes later and say, in a voice full of hurt, “You’re eating without me?”

“We called you to the table,” his daddy will say. “You didn’t come.”

“I was just finishing this one thing,” he’ll say.

“And we were finishing dinner,” I’ll say. I don’t really say that. I say nothing, because there is no arguing with the non-conformer.

Even though he gets to the table five or ten minutes after we do, he’ll still beat Husband and me to the clean plate.

Bathing

The rule in our house is you must take at least four baths or showers a week.

That might seem gross to some people, but, hey, you’re not me and I’m not you. It’s a way we make parenting easier on ourselves.

The problem, however, is that when boys get old enough to take a bath or shower on their own, they no longer have the drive to do so.

My nine-year-old sort of decided he was ready for showers this year. The other day he came downstairs with some stringy, greasy hair hanging down in his eyes.

“Uh, how long has it been since you had a shower?” I said, trying to count back the days. I couldn’t remember.

He shrugged. “I don’t know,” he said.

“Go take one right now,” I said.

It’s not that he doesn’t want to take a shower; it’s just that there are more important things to think about and do. When I went upstairs later that same morning, he had not gotten in the shower. He was, instead, hovering around an old CD player listening to Jim Dale read him Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. When he lifted up his arms to reach for something on his desk, I nearly passed out.

And this is why we can’t have a nice-smelling house.

Bedtime

Bedtime is a challenge for any kid. The days are so much fun, and they are never done playing. For the non-conformer, bedtime is merely a suggestion.

It doesn’t matter how many times I lecture my non-conformer about how important the proper amount of rest is, he will look at me and say, “I just want to finish this book.”

And how can a mom who is an author say no to that? It’s what I hope every kid who reads my novels will say to their own parents—because it means they’re interested in the story and that they are learning to love reading.

But still. Sleep.

Sometimes he’ll come up with other things. “I’m going to clean my room real quick,” which means, in nine-year-old terms, he’s going to spread everything out that’s currently on his floor (and there are a lot of things), stack it into piles and then leave it there so it can spread out evenly across the carpet again. Ever been stabbed in the cheek by the tail of a LEGO dragon because you tripped over a scarf your son had lying in the doorway of his room? I have.

Sometimes I let him stay up and clean.

Other times I’ll find him sitting on the toilet, a book open in front of him.

“It’s time to go to bed,” I’ll say.

“I know,” he’ll say. “I’m just using the bathroom.”

For half an hour.

Going out as a family

When we’re having what we call a Family Fun Day, we tell our boys they can bring a few things with them—just not all the things.

My non-conformer, however, will walk around with a backpack that is perpetually dragging him down into a sitting position. One day we were all gathered around looking at the display of dinosaur bones at the local Witte Museum, and he had his knees bent like he was using a prehistoric toilet or something.

“Straighten up,” I said. “You’re standing weird. People are gonna think you’re…”

“My backpack’s a little heavy,” he said, after which he swung it from his back and opened it up. I was surprised (but shouldn’t have been) to see at least ten books, a billion LEGO mini figures, and a package of brand new art pencils that were losing their points every time he readjusted. The inside of his backpack was a colorful display of accidental pencil marks.

“What could you possibly need all of that for?” I said.

He shrugged. “In case I get bored.”

This has been the case since he was a little boy. We’d take him to the park down the street, walking the entire way (it’s only half a mile), and he’d shove coloring books and art pads and novels into his backpack, thinking he’d sit and draw or maybe read instead of playing on the playground equipment.

He never did. He would only complain about how heavy the backpack was on the way back. I would let him carry it anyway. Natural consequences.

He never learned, though. He still carries a backpack everywhere—like to the museum today.

Later that day of the museum outing, Husband found me sitting on a bench inside the children’s area, where the kids were playing dodgeball, climbing ropes (don’t worry, they were made to be climbed), and pumping their legs on exercise bikes.

“What are you doing?” Husband said.

“My backpack was a little heavy,” I said. “Thought I’d sit down and let my back rest for a while.”

Husband tried to pick up my backpack and was nearly thrown off the bench. “What do you have in there?” he said.

I shrugged. “A few things.”

He opened it up, rifling through at least three books, some National Geographic magazines, and a couple of writer’s notebooks. His eyes were wide when he turned back to me. “What could you possibly need all of this for?” he said.

I shrugged. “You never know when you’ll have a minute to yourself,” I said. “I come prepared.”

He shook his head and eyed the nine-year-old. Then he looked back at me. He seemed to be saying something with his eyes.

I have no idea what it was, but before I could ask him, my non-conformer plopped down on the bench next to me, unzipped his backpack and took out his notebook.

“Told you I would need it,” he said, before burying his face in the blank page and writing.

You could hear Husband’s laugh in the next town.

This is an excerpt from Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On, the fourth book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Helen Montoya Henrichs.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Some days I know the truth, and some days it gets buried so far beneath those old lies I can hardly remember its echo.

This morning I woke up feeling out of sorts. Not unexpected, since there is a baby who had trouble sleeping. Since there was a brain that just wouldn’t turn off. Since there is work that has, lately, followed me right into sleep.

But this was something different. Something deeper.

This was me. This was my body. This was lie, a pair of them, rising up from the graveyard, where I thought I’d buried them long, long ago.

You see, I wrote an article about a woman’s body after pregnancy that got a whole lot of attention, and here came all those haters, hating. Their voices stirred those ghosts from their graves. While I was sleeping, the corpses came walking, and when I looked in the mirror this morning, they opened their mouths to speak.

Six weeks you’ve had, they said. Six weeks you’ve had to lose that belly. AND IT IS STILL HERE.

And then they smiled with their rotten teeth and told me the worst part of it all: Unbeautiful. This is unbeautiful. You are unbeautiful.

I could not argue. Not right now. Not today. Because today, this moment, their words feel true.

///

The first time I heard their voices, I was too young to know them for what they were. I listened to commercials and all those teen magazines and the Hollywood ideal of thin and pretty, and I stopped eating lunch when I was twelve. I stopped eating breakfast when I was a freshman in high school. I stopped eating the last meal of the day my first day of college, because, for the first time in my life, there was no one to monitor what I ate or didn’t eat.

I thought I could get away with it and that I would finally reach my target weight, which was bony and completely and utterly fatless. But I had a roommate who cared. She noticed my rapidly dropping weight and dragged me to dinner at a dining hall every chance she got. So it wasn’t long before I started purging those suppers.

I would walk with her to the dining hall and eat whatever I wanted, and then, when she was preoccupied with our friends across the hall, I would slip off to the bathroom and do what needed to be done. When she noticed, I made my excuses. Something I ate made me sick. Stress. A virus, maybe. She didn’t buy it, so the next stop was laxatives, because that was easier to hide. It was my course load, the pressure to make good grades, the stressful news job that kept me in the bathroom all the time. Laxatives got me through the rest of that semester.

Bulimia never really had my heart, though. I much preferred anorexia. So as soon as I moved off campus, I returned to the familiar hunger pains. I kept cans of green beans in the pantry, and the days I felt especially hungry, I’d allow myself one can a day. My roommates were too busy to notice.

Then I met my husband, and there came a night when he left a note on my computer at the newspaper office.

Skinny does not equal beautiful, it said. And for some reason, I almost believed him.

I looked at that note every time I sat down in my office chair and every time I got up to leave. It rescued me before my heart could stop from the sickness, but there are other ways to die than the physical ones, and I was already well on my way, gripped by the compulsive claws of anorexia.

///

Today is a reckoning day, six weeks postpartum, a day when I will visit my doctor again and stand on that scale. A scale that will tell me how much I have left to lose. A scale that will tell me, just a little bit, who I am now.

I hate that this is so. All this time I’ve stayed away from the scale, because I said it didn’t matter, and I meant it this time. I really did. This son is my last baby, and I just wanted to enjoy him without worrying about what I look like. And that’s exactly what I did. Until now.

I dressed for the morning. Those after-pregnancy transition jeans fit. A transition shirt hid the pooch. I got my hopes up, I guess.

And then I walk in the doctor’s office and I step on the scale and I see how much weight is left, and I crumble. I thought it would be different, not as quite much, not quite as ugly. Those voices start their howling.

Guess you should have tried harder, they say.

Guess you should have exercised more, they say.

Guess you should have worried about it a little more, instead of indulging in your son, they say.

I try to swallow the disappointment, and then the nurse takes me to a room with a mirror, and I have to look at my body before I wrap a flimsy sheet of paper around it, and I can’t help it. I turn away, because I don’t want to look. I know what’s there. Sagging skin that may or may not shrink back this time, because this is the sixth time. Lines that mark my midsection and a belly button that’s hardly even a belly button anymore it’s been stretched and pulled and rearranged so often.

Those voices grab all of it and fling it right back in my face. Right back in my heart.

This is what unbeautiful feels like.

///

Just after the first was born, I did not know how a woman’s body worked. So when he slid out and my belly turned to mush, I cried. It wasn’t supposed to be like this. I wasn’t supposed to look like this.

Our first day home from the hospital, when my body had only spent thirty-six hours recovering from a thirteen-hour labor, I went for a walk, because exercise has always been my crutch. Three weeks after he was born, I was out running, with a uterus that hadn’t even fully shrunk and hips that were only just sliding back into place and joints that couldn’t really take the jarring pressure of five miles. I didn’t care. I pushed it anyway.

When I injured myself, because my body wasn’t ready for what I was demanding of it, I quit eating. I pretended I wasn’t hungry. I let my husband consume those meals people so kindly dropped by.

And then one day he shook me by the shoulders. You have to eat, he said. This isn’t the way to do it.

I knew he was right. But it was so hard. So hard. Because every time I looked in the mirror, what I saw was unbeautiful.

Anorexia makes it hard to see anything else.

///

So this is what unbeautiful feels like.

It feels sad and sharp and hard and achy and impossible and shocking. Most of all it is shocking.

We can go whole years knowing and believing and living the truth, and then one thing, one tiny little thing, can raise the dead and make them walk again. It happens for many reasons, this feeling unbeautiful. It happens because someone drops an insensitive comment about our bodies that hits us right where it hurts. It happens because we live in a society that tells us skinny equals beautiful and don’t you dare argue. It happens because we look in the mirror and the body looking back is not the one we think we need or want.

Unbeautiful, the kind that makes us starve or cut and bleed or stick a finger down our throat—it is a sickness. An addiction. A compulsion. There is no real cure, at least not one that will last forever. There is only one day at a time.

Every day we are offered the choice to look in the mirror and shake our fists at those living-again lies and say: No. I don’t believe you. This body is not unbeautiful. It is strong. It is amazing. It is the loveliest beautiful there ever, ever was. Because this is the truth.

Or we can believe the lies. Believing the lies locks us into our harmful patterns of skip the food, binge and purge, count calories to the utmost accuracy.

I want to embrace the truth.

So after my doctor finishes her examination and releases me and walks from the room, I return to the mirror, and I dress again and then snap a picture, because I want to remember. I want to remember the day I looked at my body and finally, finally, finally said out loud, if only to myself, what was true: This body. I am so very proud of what it has done. It has housed and carried and nourished six boys and a girl we will meet in glory. So what if there is still an after-belly six weeks later? THIS BODY HAS DONE SOMETHING AMAZING AND BEAUTIFUL. It needs to revel in that. So I will let it take its time.

And I mean it.

Those corpses, the anorexia and bulimia that have breathed down my neck all morning, start crawling back to their graves, because you know what? They know, too.

This is what beautiful feels like.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Ian Schneider on Unsplash)