by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

If you want a lesson in focus, try having a conversation with your partner while your kids are home.

At the end of every day, when Husband and I have put away our work for the evening, we try to have a quick run-down of what happened—highs and lows that we’ll share, somewhat, at the dinner table but in a kid-friendly way. Husband is usually finishing up dinner and I’m usually hovering and stealing pieces of the turkey burgers he’s making, while he tells me about all the contacts he made today and I tell him about all the words I wrote (one of these is clearly more interesting than the other). We’re interrupted an average of forty-five times in a five-minute conversation. And when we turn our attention to the kids, usually they forget what they were going to say in the first place.

The other time that we can nearly always count on (halting) conversation is when all the kids are strapped in the car and we’ve turned up the radio, full blast, so we don’t have to hear boys tattle. That doesn’t work, of course, and oftentimes, Husband and I will wish for a police car glass separating the front seat from the back. Why aren’t there cars like this made for parents yet?

In any of the instances when we think it would be a perfect time to approach a conversation, we are invariably and constantly unsuccessful.

Conversations when you’re a parent really have one defining quality about them: constant interruption.

It doesn’t matter at what point in the conversation you are. You could be almost all the way done with what you need to say, and miracle of all miracles no one has needed you for the last fifteen minutes—but now you’ve gotten to the most important part. And, of course, one of your kids will need you as soon as you start in on the finale. They will need you for the silliest of things—one will wonder how many galaxies are in the solar system, and you won’t have the slightest clue. Another will need you to ask what 4,567 multiplied by 9,327 is, as if you’re some kind of math whiz and didn’t forget how to even add numbers after you finished your required college algebra class.

Sometimes you’re interrupted because they happen to hear their name, even if they’re in the middle of singing their favorite song at the top of their lungs. They will hear their name and perk up and then proceed with an interruption to ask what you’re talking about. I remember my mother calling me Rabbit Ears, because I could always hear my name even when she was saying it a couple of rooms removed from mine, to someone other than me. Well, now I understand this phenomenon. I have been blessed with six rabbits, and one who will, without fail, interject into the conversation the question, “Are you talking about me?” The others, at least, will close their mouths and quietly listen.

Even if we whisper their names, they will hear it. We’ve done it just to test this theory. It’s quite astounding, because they can’t seem to hear their names when we’re actually talking to them. Weird.

We’ve tried to teach our boys to say “Excuse me” or “Pardon me” or to wait until a break happens in the conversation to tell us what they have to say, unless, of course, it’s an emergency. (The emergency definition gets a little lost in translation, too, but that’s a topic for another day.) On the good days, a boy will place his hand on one of our arms and wait patiently for the talker to finish—but it is extremely hard to finish a point when you have large brown eyes staring at you like they’re wondering if you’re ever going to be done talking. If that doesn’t steal your thought from the track down which it barreled, then you are more skilled at conversation than I am.

When you’re a parent, conversations with your partner will sometimes last for days—and if you’re really, really good, weeks. Sometimes you’ll even think you had the conversation and you didn’t at all. It was only wishful thinking. You will have mapped out the entire conversation in your head, and then on the day of your doctor’s appointment, your partner will say, “I didn’t know you had a doctor’s appointment,” and you will get mad at him, because he never listens to anything you have to say, when the real explanation is that the conversation never happened at all, except in your head. You were communicating with a figment of your own imagination.

Other times, you’ll forget that you already told your partner something, and you’ll delightedly repeat the same story twice, to a bored and disappointing reception.

There are so many times that I am right in the middle of saying something and one of my boys will start crying because a brother kicked his lip and made it bleed, or maybe someone just needs us to know that his poop was green today, and I can’t for the life of me remember what I was saying. Have you heard the old saying “If you forget what you were trying to say, it must not have been all that important?” It turns out that if you forget what you’re saying in the middle of saying it because your kids interrupted you, there is no guarantee that it is not important. I know, because none of my boys had signed permission slips for their field trips this year, because I forgot to tell their daddy they were due.

Husband and I have had the longest conversations with the fewest words while living with six boys. Here’s an example of one of those conversations:

Me: Hey, I wanted to talk about the supplies that we’ll need for this weekend’s birthday party.

Husband: Let’s make a list.

Kid 1 interruption: Mama, my brother took the ball from me.

Me: [mediating a fight over a superhero ball that is completely flat. Someone wants to play soccer with it, even though it’s a flattened ball. Someone else wants to wear it as a hat. Everyone had it first.]

Fast forward half an hour.

Husband: Now what was that again?

Me: I forgot what we were talking about.

Husband: Me too.

[Collective laughter.]

Me: Oh, yeah, the birthday party.

Kid 2 interruption: Mama?

Me: I’m talking to Daddy. Just wait a minute. Don’t be rude. Remember what we taught you about interrupting?

[Kid 2 places a hand on my arm and watches me intently.]

Me: I can’t think. Let me just see what he wants.

[Engaged with a kid who wants to know if he can start a business selling art. Today. Right this minute.]

Fast forward another half hour.

Husband: [with a good amount of sarcasm.] Back so soon?

Me: Where were we?

Husband: I don’t think we’d even gotten started.

Me: The birthday party. You said something about ca—

Kid 3 interruption: Excuse me, Daddy?

Husband: Mama and Daddy are talking. Please don’t interrupt.

[Kid 3 places a hand on Daddy’s arm and watches intently for a break in the conversation.]

Me: So cake and plates and cups.

Husband: I’ll make a list and pick some up at the store.

Me: That would be good.

Husband: Chocolate?

Me: Yes. And green.

Husband: Snacks?

Me: Yes. And make sure the cups are recyclable.

Husband: Got it.

Me: One more thing—

Kid 1 interruption: [crying] Mama, Daddy?

Husband: Maybe we should talk later.

Kid 1: My brother hit me.

Husband: [turning to Kid 2] What did you want?

Kid 2: I forgot. You were talking so long.

Kid 1: Can we watch a movie?

Kid 3: Did you know that a shark can smell blood from 40,000 miles away?

When Husband and I “finish” a conversation, it’s usually a day after we actually start it, when kids are entertained out on the trampoline until someone takes a leap into someone else’s knee and comes in limping to tell us all about it—with a little exaggeration thrown in for good measure.

All I know is that my focus is much more efficient now. I can keep a running commentary going in my head all day. The real challenge is remembering what I’ve actually said to Husband and what I’ve only said in my imagination.

Ah, well. Husband and I won’t even finish the argument we’ll have before a kid will interrupt us with a stink bomb and a proud declaration that they win the Rotten Smell Tournament.

As if one ever existed.

This is an excerpt from This Life With Boys, the third book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

Photo by This Is Now Photography.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

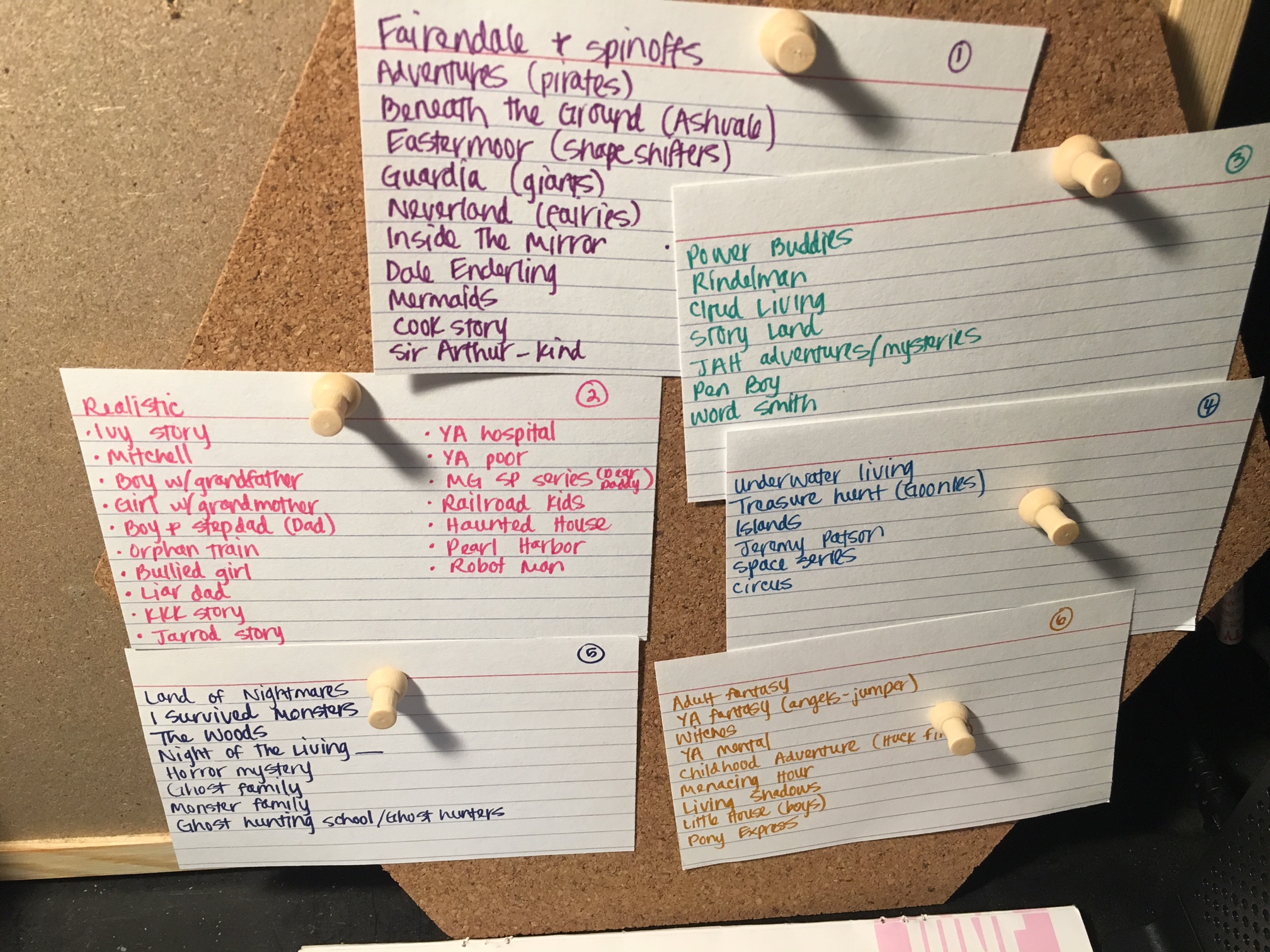

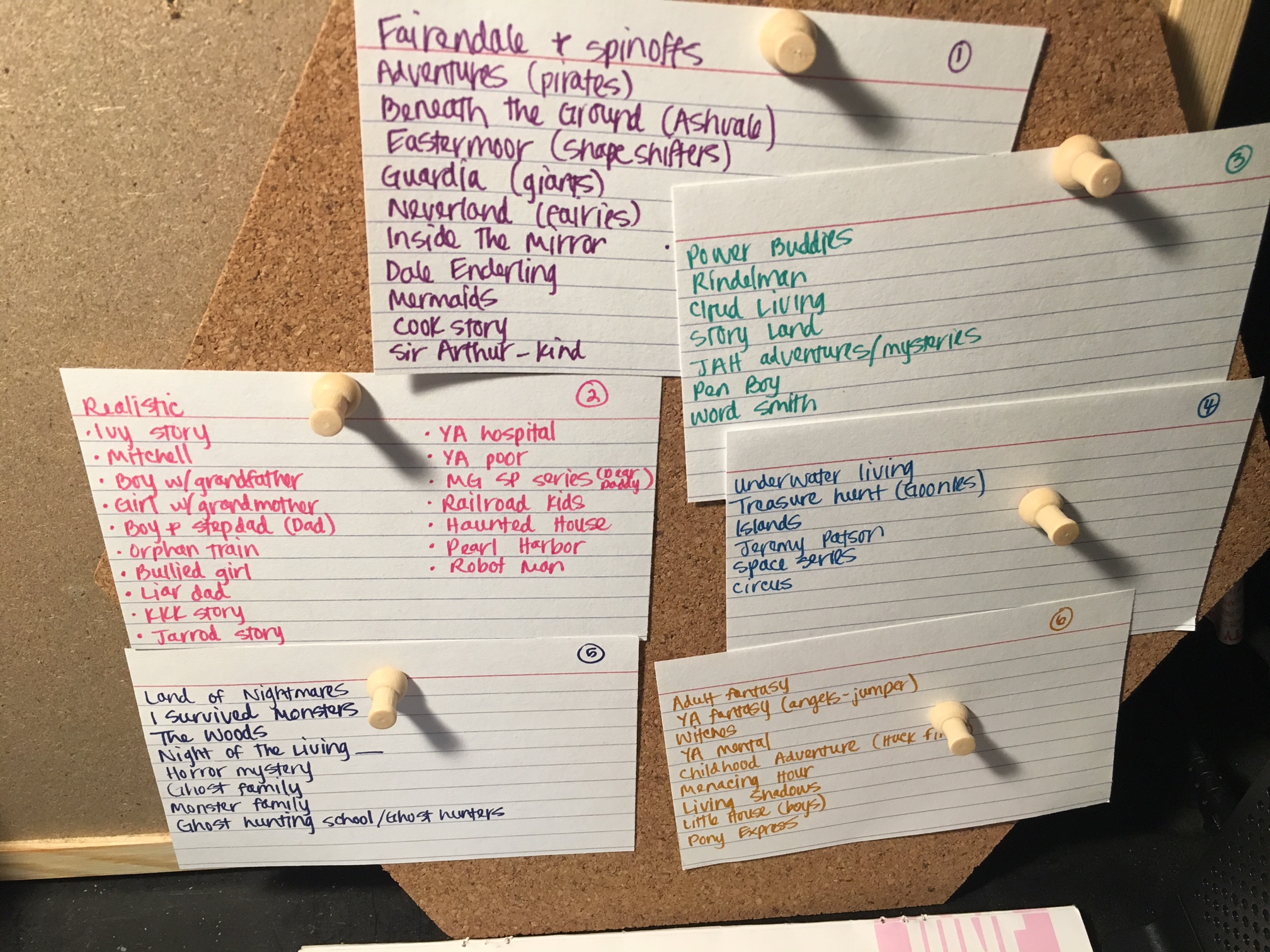

Last month I talked about the importance of capturing your ideas in some way or another. I use index cards to jot down every idea that visits me, and that has worked well for me. It’s up to you how to capture them; it’s only necessary that you do.

But what happens to those ideas once you’ve captured them?

Again, you’ll have to find your own way through this (you might be more digitally oriented than I am), but I use a system of multiple photo boxes. Multiple stories are collected in each box, and each box is assigned a number. I have a key that tells me which story corresponds to which box.

The challenge, for me, is that I am never only working on one story at a time. I have so many ideas that are always working themselves out in the background, which means I need to have a system of, for example, collecting poems I read that might be brainstorm material for a story I write years from now. Or remembering a location that sounds interesting but doesn’t have a story yet. Or recording a character I want to write whose story I have not yet heard.

These boxes keep all of that safe and somewhat organized (about as organized as I can get).

I keep the boxes in my closet, and when I am ready to begin the long work of a story, I take out the box, examine all the notecards that I’ve collected, and begin on the research and brainstorm portion a few steps ahead.

This capturing system works well for me, although my husband complains that our closet doesn’t have enough room for shoes anymore. Who needs that many shoes?

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

There is something every parent should know before they attempt this climbing-Mt-Everest-without-an-oxygen-pack-or-a-partner-or-warm-clothes task of tidying up a house: Children will follow along behind you and undo all your hard work.

There are a few times a year when I decide I’ve had enough of my filthy house. Most of these times are not weekends we’ve sent kids away with their grandparents and could actually tackle tidying and cleaning without kids underfoot, because who wants to spend a weekend without kids cleaning? Nope.

So most of the time, when I’m fed up with filthy, my kids are home, waiting to undo everything.

If both parents try to tackle the project, it’s much worse. One day Husband went upstairs to clean, while I was downstairs trying to clean, and no one was really paying attention to the 3-year-old twins, and they unraveled three rolls of toilet paper and tried to see how much of it they could stuff in the toilet with the plunger. I was in the kitchen, trying to scrub the counters that hadn’t been wiped down in too long by anyone other than an in-a-hurry-to-get-my-chore-done boy.

Once I turned on the vacuum cleaner, the boys saw it as their free pass to take out All the Stuff because Mama couldn’t hear them.

Every now and then—not often—I get a REALLY wild hair and decide I have to clean everything—under couches, under the stove, under the refrigerator, the tops of everything you can’t really see and usually leave to the dust. I’ll move all the furniture and find stockpiles of Hot Wheels and broken pencils and crayons and food they’re not even supposed to eat in the living room. The problem is, as soon as I pull any of it out, the boys take off with it. They’ll play with the cars, they’ll sharpen the pencils, they’ll eat month-old bread (I know. Gross). I don’t even have a chance to put it all in the trash before it’s already disappeared.

I guess, in reality, that saves me a step—putting it all away—but they really only end up displacing it somewhere else in the house, where it will most likely find its way back underneath the couch.

On these not-so-frequent, clean-everything days, I’ll tell them, “We’re cleaning the house today” but to them, these words have no meaning. That’s not true. They have meaning. It’s just a different translation.

Children don’t understand cleaning and tidying language.

“We’re cleaning the house today” means get out all the papers and scribble one little thing on them and call it finished, and then, when you’re tired of that, take out a few books to read and make sure you leave them on the floor, and then, when you’re tired of that, go outside and play for three seconds and bring in forty rocks for Mama—make sure you say they’re for Mama, because this is how you know they’ll definitely be kept, except this time Mama is being really mean, and she makes you take them back outside, and she’s the worst mother ever. Well, fine, you just won’t give her anything anymore, then. At least until you see those weeds in the yard with the purple flowers and pick them all so you can toss the bouquet at Mama, because she’s vacuuming, and it’s the perfect time to throw pretty things at her.

“No more toys out right now,” means, sure, Mama is cleaning, trying to pick up all the stray cars, and you’re not supposed to play with any toys right now, but there’s still the art cabinet, she didn’t say the art cabinet was off limits, so you go and take all the little cups with the crayons out, even though you only really need one, oh, and make sure you open the bottom cabinet and take out fifteen of the coloring books, even though it’s not even possible to color in that many at a time. Be sure to make the rest of them topple over so they fall completely out of the cabinet. Color for a few seconds, and then forget that’s what you wanted to do. Go upstairs to your room and find the hundred things you’re going to bring back down with you and then, when you’re bored with making that kind of mess, go into the pantry, because Mama’s not looking, and grab a mason jar of almonds and fill it with roly polies, after you eat all the almonds, of course, and then bring them back in and hide them in the pantry so Mama will never know you ate a half pound of almonds in one day.

“The bathroom is off-limits for the next thirty minutes” means Mama will be so focused on getting the urine—from toilet misses, not purposeful peeing on the floor—that you’ll be able to get into the games cabinet and take out Lord of the Rings Risk, with its billions of tiny little pieces, which you know she must hate, since she’s always telling Daddy they should get rid of it, and he’s always saying he can’t get rid of it, because when you’re older you’ll want to play it with him, and you think, of course, that it’s the best game ever, because A BILLION PIECES (!) you can spread all over the floor Mama just vacuumed. Make sure you dump them ALL out and, when you’ve put them all on the Middle Earth map, decide it’s probably time for a break, and leave the pieces where they are so your 3-year-old brothers can knock them all off and they’ll slide under the couches and make Mama mad—but you’re off the hook, because the twins did it.

“I’ll only be upstairs for a minute” means you now have the opportunity to follow along behind Mama as she picks up every single stray book on the library floor and shelves it, biding your time until she moves into your bedroom to make sure it’s clean, and then your little brothers’ bedroom to make sure they didn’t empty the closets again. Wait until she’s in her bedroom, because she always gets stuck in there, and then pull down all those titles in the Harry Potter series, because before you start to read one of them, you must, naturally, see them all. Leave them on the floor, because book carpets are the best.

“Everybody stay out of the dining room” means that while Mama’s wiping down the table and cleaning all the glass, it’s your job to sneak all those cups down from the cabinet and fill them with water and put three of the Lord of the Rings Risk pieces in them and then into the freezer to see what happens to figurines when they freeze. Mama will probably never notice. Grin to yourself, because you’ve just successfully thwarted all your parents’ efforts to clean and tidy the house.

This is an excerpt from The Life-Changing Madness of Tidying Up After Children, the second book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Around Christmas time one year, when my oldest son was four or so, someone asked him if he’d been good this year. It was an innocent question, a question people often ask children because it is, in the folklore of contemporary life, tied to the gifts that might be waiting underneath the tree come Christmas morning.

My son was never one for masks and pretending. He said, “I’ve been a little good and a little bad.”

And it was true; he had.

This contradiction lives in all of us. We all have the capacity within us to be a hero one day and a villain the next. We all have a measure of good that is countered by a measure of evil (though we are not, ourselves good or evil; we are simply human). We all struggle wrestle with both light and darkness.

I want, more than anything, to be kind in all ways. I desire to make every interaction count. I hope, always, to be an ever-present, encouraging voice.

And yet there are times I feel myself overcome with emotion—so overcome that my greatest desire is to lash out and hurt, to say words that I know I’ll regret later, to feel the power, however convoluted or corrupt it is, of being on top for just a moment in time.

There is a mean bone in all of us that wants to feel like we matter in the grand scheme of things, that we belong somewhere, that we are people who have a small pinch of power.

These contradictions that exist within all of us are relatively harmless—when our thoughts remain thoughts and we remain vigilant. When we recognize, accept, and restrain them.

In these contradictions, we can feel the connection of humanity—the dark impulses rising up in us that we can imagine rise up in everyone else, too. If we sit with that darkness for a while, we can understand the impulses that govern the cruel, we can measure the capacity for harm, we can almost, maybe just a little bit, fathom why this cruelty sometimes spills out into the fraught spaces of the world.

But if we deny these dark places within ourselves, if we say of course we have never had a terrible thought about another person, if we do not at least momentarily acknowledge and connect with that side of ourselves, we will never completely understand the failures of some to control it.

And, what is more, when our darkness is ignored and denied as though it never existed at all, it becomes stronger and more difficult to control.

If ignored and denied long enough, we could fall into the gap between our real selves and our imagined (better) selves. And once in the gap, the darkness does not have to work hard to best our control, to control us instead of the other way around.

Better to deny or acknowledge?

I know which I’d choose.

(Photo by Cherry Laithang on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

When you puff their petals,

they lift off into the sky,

tiny pinwheels twirling

on hopes and wishes and dreams.

It’s uncertain where they’ll land—

but it’s certain they’ll land.

And when they do,

they’ll grow another weed

that will release

another handful of

hopes and wishes and dreams

into the sky—

Which begs

the question:

weed or

flower?

(Photo by Dawid Zawila)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

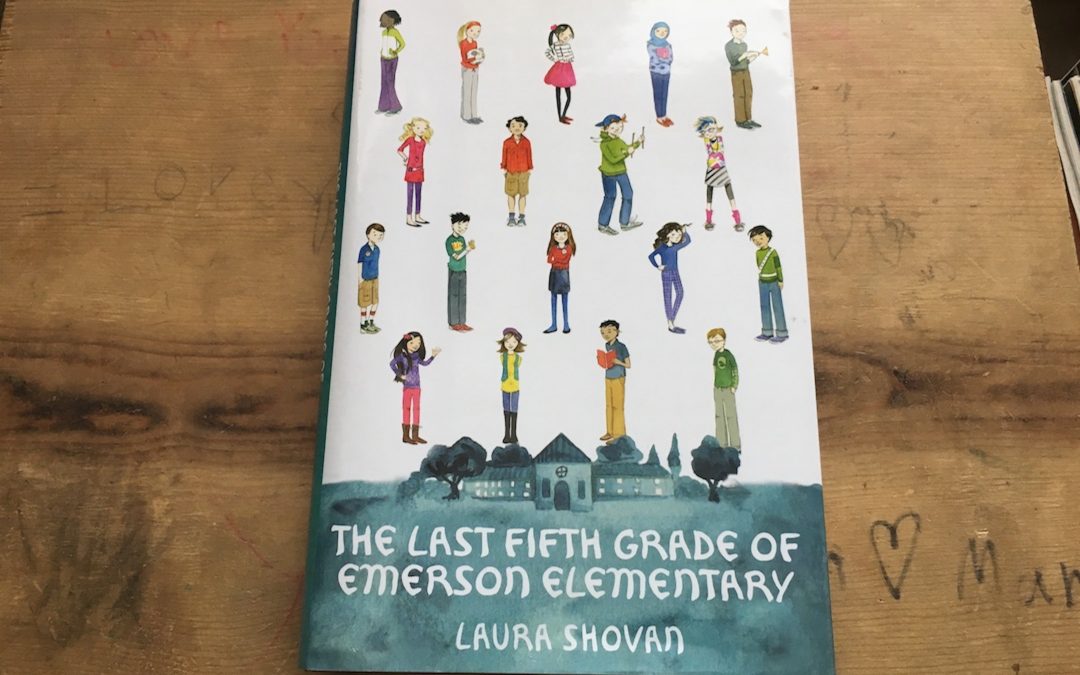

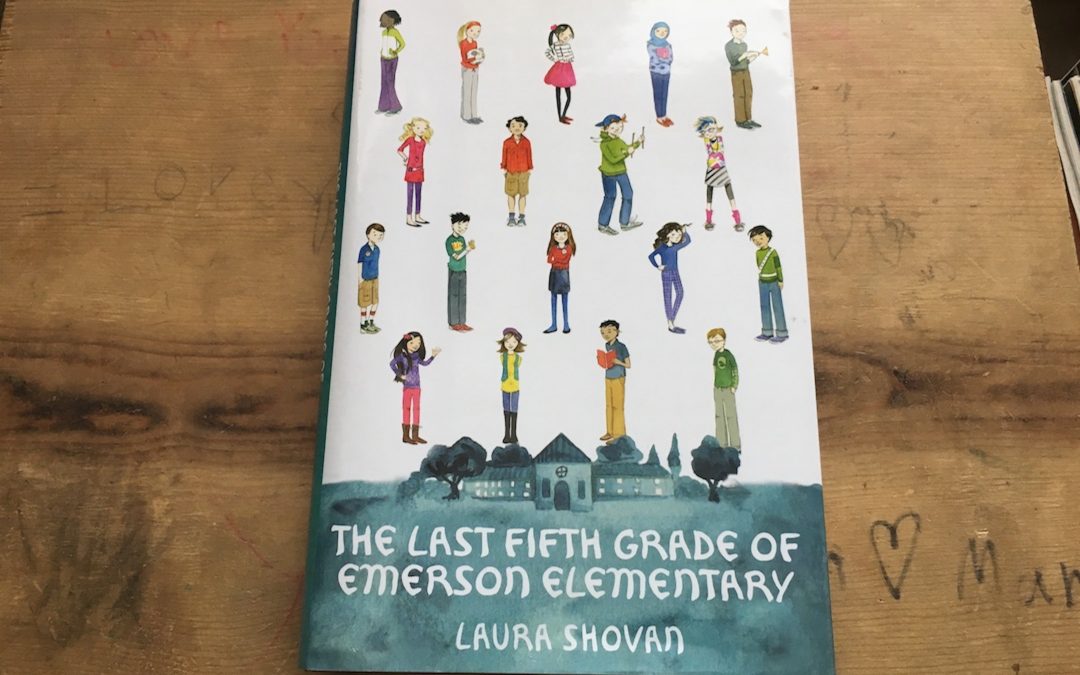

I’ve always loved novels in verse, and lately I’ve been exploring more and more of them; they seem to be a hidden genre of storytelling that is lovely, insightful, and satisfying to my poet’s heart.

Plus, I’ve written a novel in verse. I’m trying to explore and better support my fellow poets.

For the last several months, I’ve been sort of touring through the well known and little known titles that are novels in verse. The Last Fifth Grade of Emerson Elementary, by Laura Shovan, was one of the most spectacular of my recent reads.

I don’t know if it’s because I have a son who recently graduated fifth grade and will be going into middle school next month or if it’s simply that this was a story well told (it was, and it’s likely both), but I could not stop thinking about this book for days after I’d finished reading it.

It was a phenomenally executed novel in verse, with so many compelling characters (each student in a class of fifth graders is given several poems throughout the book) and their everyday realities and anxieties and home happenings captured in verse. Each poem told a story about the student who had written it, and yet all the collected poems told a larger story about an elementary school getting closed down for demolition and the students who wanted to protest that future. It was amazingly intuitive and brilliant.

Here are three things I liked most about it:

- The poetry. This book was like nothing I’ve ever read, a combination of structured poems and free verse—but what stood out most about each of the poems was the characterization captured within. It was so well done I’m misting up even as I write these words.

- The emotions. Because the poems were written by different students and sort of shuffled up throughout the book, they subtly showed the struggles of each student: some were dealing with parental divorce, conflicts with parents, conflicts with friends, all the things fifth graders deal with in their lives. There was tension and a story told in every poem, however long or short.

- The concept. Not only were these kids finishing up elementary school, which is a huge transitional time in a kid’s life, but they were also trying to save their school from being torn down—so double the transition (they would never again see this place where they’d spent six years of their lives; that’s a difficult thing). It really was brilliantly done.

Shovan just came out with a new novel, Takedown, which is not written in verse but contains her poetic language and her insightful character development. It will need a post on its own.

You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll feel so many emotions reading The Last Fifth Grade that you’ll never forget it. Truly a classic that should be read aloud to every fifth grade student so they feel seen and heard and understood. Thanks, Shovan, for giving me this gift to read with my son.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

Husband and I recently received a communication from our son’s fourth-grade teacher. Recess, the email said, was temporarily suspended for some problems kids were having on the playground.

They have since rescinded their punishment of the kids and found an alternative to it, but the possibility of these no-recess days got me thinking about the expectations we hold for young children—especially boys—in our schools.

Because I’m a mom of six boys, I get to see many different personalities slide out in the course of boy play. And even while one will choose to build quietly with wooden planks for his free play time and another will reach for a book and another still will race out to the backyard shrieking like a banshee and thrusting his pirate sword into the belly of an imaginary enemy, there are some things that come pretty standard in boy play.

1. They run.

On our walk to school, my sons can’t simply walk. They can’t. They run the entire way. I always say this is why I wear workout clothes most days—I have to keep up with my sons somehow. This is only halfway true…the other half of the truth is that I didn’t get a shower today, and, also, it’s a thousand degrees in Texas; may as well sweat in actual workout clothes. It somehow makes it better.

My standard footwear is my cross training shoes, because there is absolutely no telling when I will have to break out into a sprint to save a boy from a mistimed run or a fall that happened when they were engaged in a race with themselves.

2. They shriek.

No matter what boys are doing, they’re loud. If they’re sweeping the kitchen floor, they’re singing “Thriller” at the top of their lungs. If they’re running through the backyard playing Infected (a variation on chase, as far as we can tell, where the person who’s “It” adds an army of people who are “It”), they’re shrieking at the top of their lungs.

Incidentally, when we asked what happened on the school playground, my fourth grader said, “I don’t really know. I think a couple of boys got into a fight, but I was playing Infected, so I was running for my life.”

3. They fight.

For fun, my boys play a fight game. They call it “Slap Fight From Noon ’Til Night.” Sometimes there are variations on this fight game. Sometimes they use a superhero cape to whip the legs out from under their opponent and end up with welts on their shins. Sometimes they take plastic swords out to the trampoline and whack each other with ill-aimed blows. Sometimes they just use their hands.

This is all for fun. It’s as delightful as it sounds.

4. They bounce.

Boys are bundles of energy, and if Husband and I are doling out instructions, saying something serious, or just mushily telling them we love them so so much, my sons are forever and always bouncing. They bounce on their bottoms, they bounce on their bellies, they bounce on their knees. They bounce so much it makes me sore watching them.

5. They very rarely think before doing.

The most frequent answer to “What were you thinking” after a kid has busted his face on the side of our brick house, at which he ran full speed ahead to test his stopping reflexes, is “I don’t know.” And it’s true. They don’t know.

When my sons do stupid things like try to jump from the trampoline to the top of their dad’s shed fourteen feet away, act on their insatiable curiosity about what it’s like to pee off the top of our van, or ride down the stairs on a skateboard, I already know the answer to my deepest wondering.

6. They compete.

Whatever boys are doing, it’s a fierce competition. They will simultaneously swing across the monkey bars to see who can finish first, knocking out teeth in the process. They will race to the end of the sidewalk to see who wins on the way to check the mail. They will eat their food—practically inhale it—so they can be the first one done and in line for seconds (there is no line. We don’t even dole out seconds until everyone has finished their firsts. Does it matter? Nope.).

7. They lose all sense of time and space.

When they’re little, boys don’t have much of a sense of their body, which is why they’ll barrel into their mother, nearly knocking her flat, when they decide they want to give her a hug. They also have no sense of time. “I’ll be done in two minutes,” they say, and what they really mean is twenty.

(This doesn’t change as they get older, unfortunately. Husband will often say, “I’m almost done,” and two hours later he’s finally ready for our date night at home. I’m already asleep.)

8. They’re gross.

They compare the boogers they picked from their noses, they collectively gather in the bathroom to see poop before it’s flushed, they like nothing more than to announce to the house and the entire world, “He’s bleeding!”

On a regular basis, my boys try to determine who has the smelliest farts. They will sulfurize each other out of a room before they declare a winner—and by then no one’s conscious to celebrate.

Girls have their challenges in a society like ours; I struggle with those challenges every day.

Boys have their challenges, too, and they can be seen, most often, in the early classrooms of their childhood. It’s unfortunate that all across the nation, boys are monthly, weekly, daily punished for who they are. Of course they must learn how to take control of their bodies and navigate a social world that needs softer voices and better attention—but never at the cost of their identity.

My boys drive me perpetually crazy, but I know that one day I’ll miss being jostled on my way to the bathroom, knocked sideways into a stream of crop-dust because they wanted to get there first.

Boys will be boys. And I love them for it.

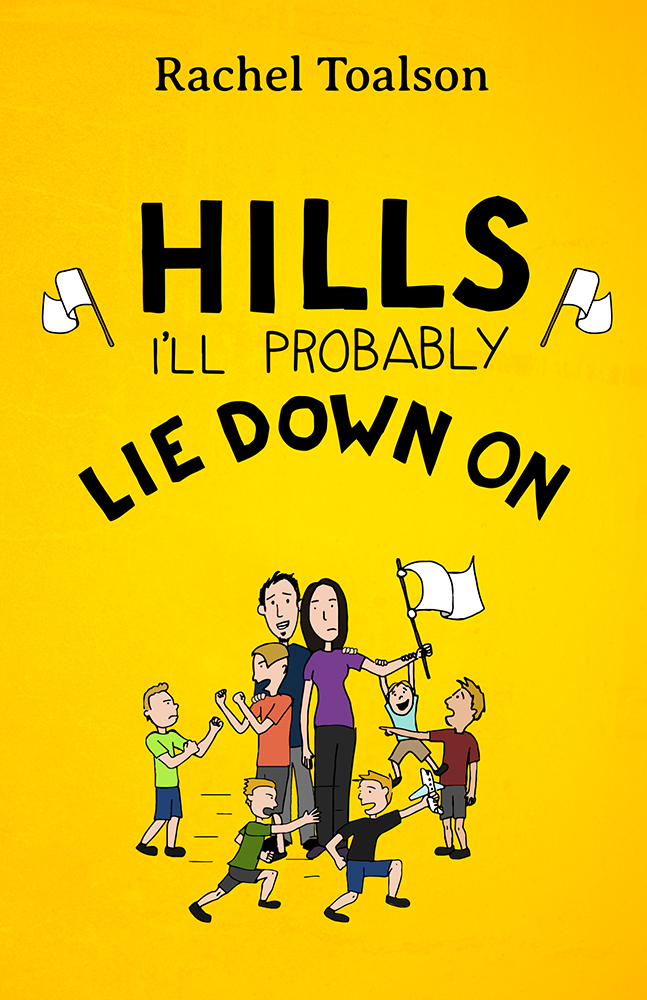

This is an excerpt from Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On, the fourth book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Helen Montoya Henrichs.)

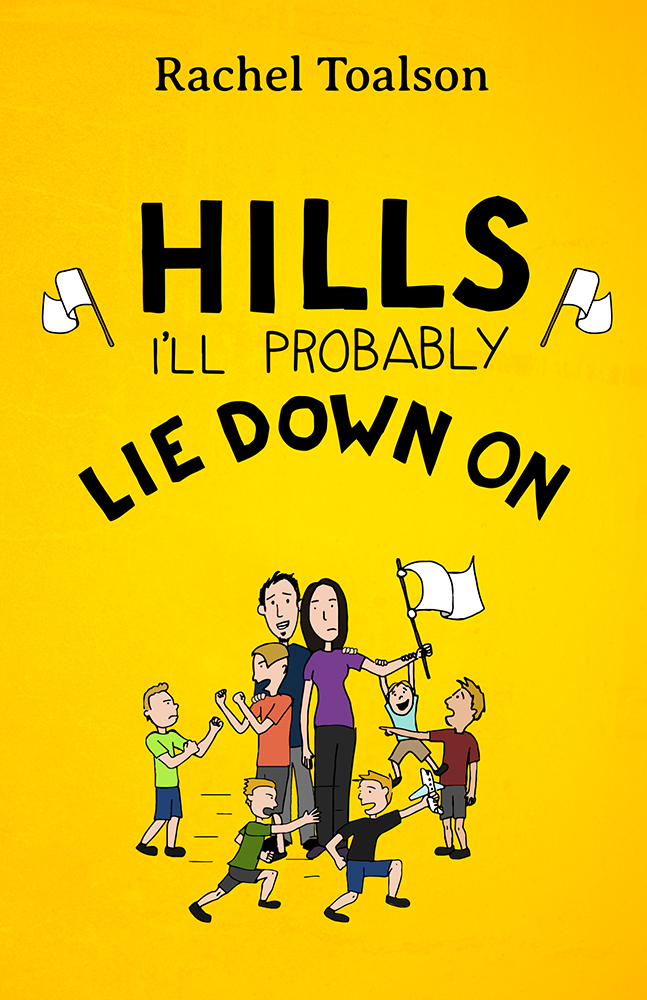

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents, Happenings

I saw him at the table, spacing out.

“What are you doing?” I said.

“Thinking about your book cover,” he said.

“Oh yeah?” I said, trying not to show my excitement; I’ve been asking him to design this cover for a while now.

He slid his sketchbook toward me, and I saw the beginnings of a perfect cover.

This is the way it normally happens: I catch Husband in a trance, he sketches, he asks my opinion, which is always ill-informed, and he designs what he wants anyway (even though I rarely have anything at all to say about a cover except vague things like, “I’m not sure I like that color,” and when he asks me what color I’d like instead, I shrug. I’m the best client ever.).

I am fortunate enough to be married to a man who is skilled at many things, including book cover design. For the Crash Test Parents series, which is a collection of books filled with humor essays, he always starts with some kind of caricature of our family and tailors that to the content of the book.

These are like digital markers of how our family has grown up and changed.

This particular cover exemplifies beautifully some of the hills Husband and I have decided to lie down on: kids being rowdy, kids fighting one another, kids tattling, kids playing chase in the house. There are many mishaps parents can focus on in a day—and I’ve found that there are much more important things than these, as crazy as they may make me feel during any random hour.

So this cover, for me, feels perfect—because not only does it depict my entire family, all these people I love, in a scene that depicts their personality, but it also includes a white surrender flag.

It says, I surrender.

It says, It’s okay to surrender.

It says, I’m so glad I surrender.

In the forefront, Husband drew our twins, chasing each other through the house, likely because of some toy one wants and the other doesn’t want to hand over. What you can’t see is what will likely happen next: one of them will trip over something and the other will crash into something, and both will start wail-crying, blaming the other.

There’s also my third son, tattling, which he loves to do, and, to the left, my first and second son, boxing. Again, you don’t see what will likely happen which is this: the oldest will get his feelings hurt because he wasn’t actually trying to box, he was just pretending.

And hanging from my arm is my youngest, who can hang as long as he wants, because he’s the baby and it’s no secret that he’s spoiled.

Not the least of all these wonderful elements is the expression on Husband’s face and the one on my face. He looks apologetic; I look resigned—which is usually the case (he is, after all, the one who is responsible for all these boys).

A perfect book cover, if I ever saw one.

More info about the book

Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On will release Aug. 14 from Batlee Press. This is the fourth full-length humor book in the Crash Test Parents series.

Blurb

Choose your battles.

It’s sage advice. But most parents, before becoming parents, don’t have a clue just how many battles kids will place in front of them with seemingly endless energy to engage. Choose your battles becomes a life-saving measure when one has kids. Knowing when to stand your ground and when to lie down is imperative in the face of such admirable yet aggravating persistence.

From the voice behind the popular Crash Test Parents blog comes a brand new collection of comical essays about the challenges and joys of parenting. With measured wit and eloquence, Rachel exposes the universal challenges of leaving the house with kids, traveling with kids, putting kids to bed, eating with kids, and, largely, daily life lived with kids.

About the author

Rachel Toalson is the author of Parenthood: Has Anyone Seen my Sanity?, The Life-Changing Madness of Tidying Up After Children, This Life With Boys, and a handful of poetry books. She lives with her husband and six rowdy boys in San Antonio, Texas.

Excerpt

For excerpts from Hills I’ll Probably Lie Down On, see one or all of the following:

Child Leashes Save Lives and Sanity

The Fastest Way to Go Insane: Try Working From Home With Your Kids Around

(Above photo by Dawid Zawiła on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

5:30:31

We link hands and pray—

this is the beginning of

every great dinner.

5:30:35

The dinnertime

discussions are my favorite things:

necessary, thrilling.

5:30:58

We get to know who

our children are, see glimpses

of who they’ll become.

5:30:59

All while they suck dry

the soup they claimed they didn’t

like; now it’s tasty.

These are excerpts from The Book of Uncommon Hours, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by Chris Lawton on Unsplash)

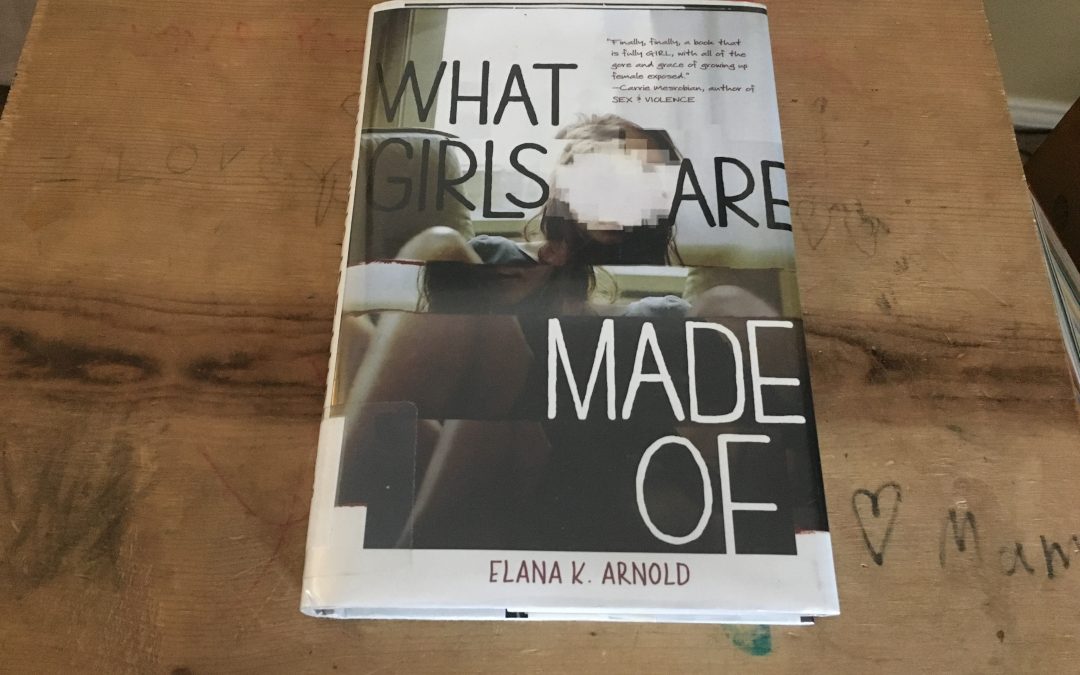

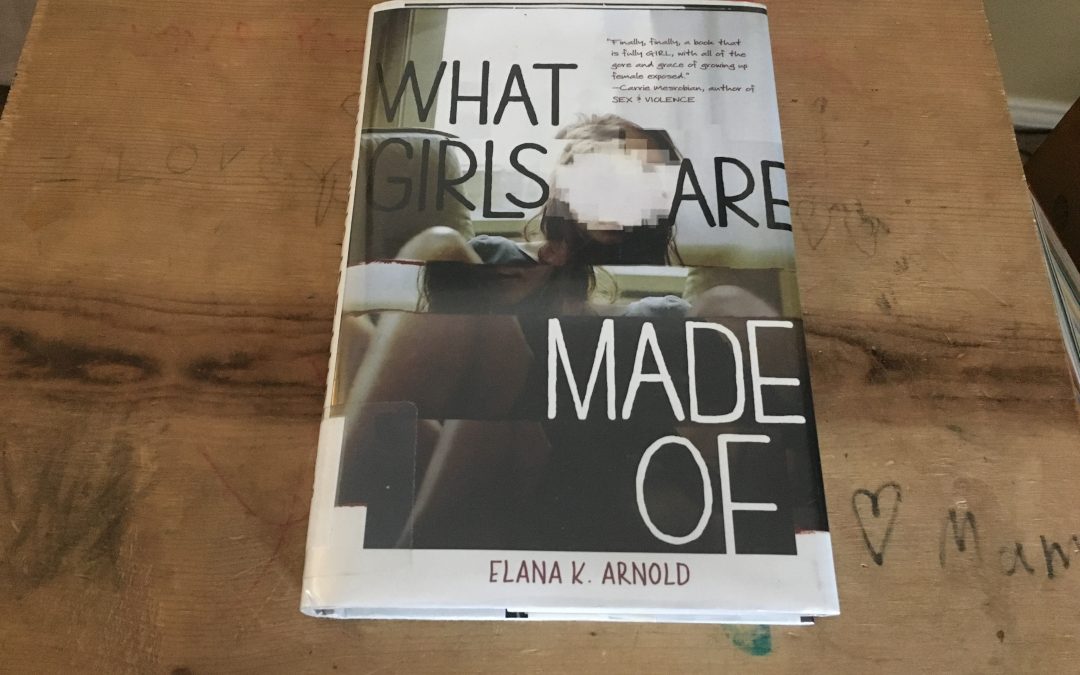

by Rachel Toalson | Books

Every now and then I am introduced to an author who has been around for a while but who has fallen under the radar for me. I’m always delighted when that author turns out to be one whose style I absolutely love and admire.

Such is true of Elana K. Arnold. While I have been making my way through her backlist, my favorite novel so far is What Girls Are Made of, which was a 2017 National Book Award finalist.

It’s a phenomenal book. It was interesting, important, and a great contribution to young adult literature—proving to teenage girls that they are seen and they can be more than who they are told to be. I wish a book like this had existed when I was a teenage girl.

Here are three things I enjoyed the most about it:

The intermissions. That’s what I’ll call them. They were stories that the protagonist, Nina, had written about chickens and eggs and female saints and all the ways, metaphorically, that women are devalued. These intermissions interrupted the flow of the narrative but served an important purpose.

The character. Though some of Nina’s decisions were not ones I would have made myself, I really enjoyed her personality and the growth and change she experienced in the story—one that showed her she was good enough on her own, as a young woman.

The structure. Not a whole lot happened in the book, but what did happen was intriguing, and it was interspersed with such interesting flashbacks and the stories that Nina had written for her English project. So even though not a lot happened plot-wise, a lot happened theme-wise, which are sometimes the best stories.

The first line was compelling and intriguing:

“When I was fourteen, my mother told me there was no such thing as unconditional love.”

What? You have to know more about this woman and her fourteen-year-old daughter.

Overall, What Girls Are Made of was a book I would likely read again. I loved its message and its shape and its truth. Lovely, real, hard, and ultimately necessary book for today’s teen readers.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.