Coffee: a Wondering

If a spoonful of sugar

makes the medicine

go down, then

what does a

spoonful of coffee do?

One sweet,

one bitter,

opposites—

if not completely,

then at least

marginally

Does coffee, then,

make the medicine

come up?

If a spoonful of sugar

makes the medicine

go down, then

what does a

spoonful of coffee do?

One sweet,

one bitter,

opposites—

if not completely,

then at least

marginally

Does coffee, then,

make the medicine

come up?

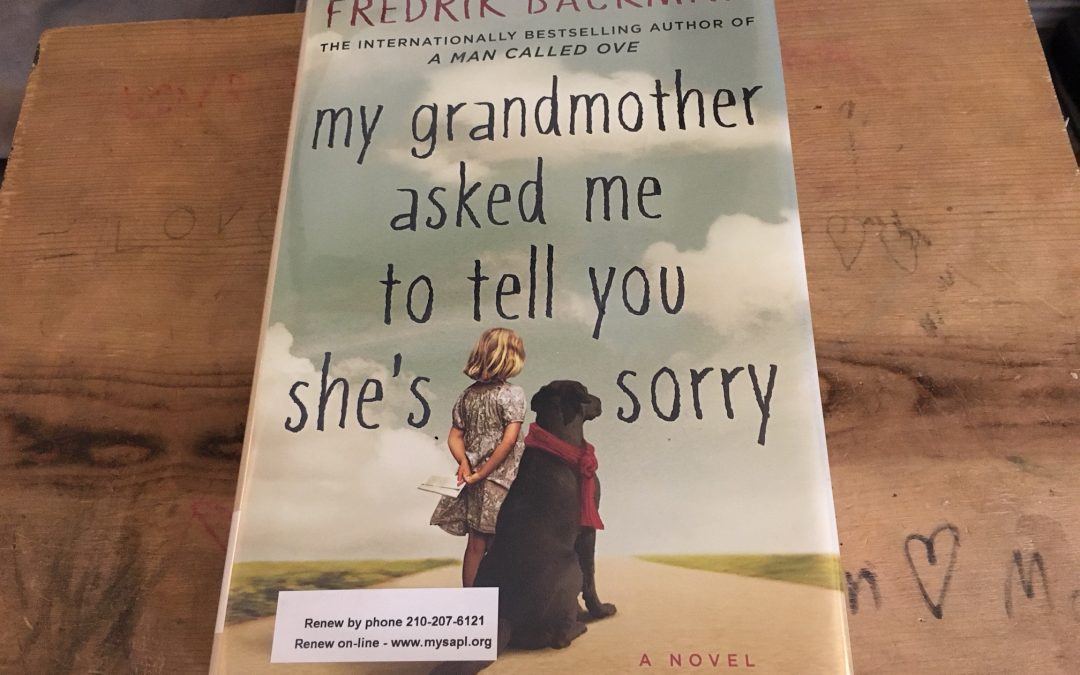

Once again, here I am raving about Fredrik Backman. I have become a superfan of his, after reading A Man Called Ove, and, now, My Grandmother Asked Me to Tell You She’s Sorry.

This book. How do I even begin? Funny, charming, heartbreaking, hopeful, sweet are just a few of the things I’d say about it. It’s a story about a little girl, a dog, and a spunky grandmother.

Backman has a gift for telling the kind of stories that will remain in your heart and mind long after you’ve finished it. This one is yet another that fills my thinking space of late.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The personalities. Backman has a way with characters. It’s like he studies human nature at length, and then he brings those characters to life on the page. They are so wonderfully tragic and funny—which describes the book as well.

The story. This story was, at its heart, about the redemption of an old woman who had worked so much that she was not considered a good mother to her daughter—but there was a reason, of course, for why she did what she did. (You’ll have to read it to find out the reason.)

The imagination. Elsa’s grandmother would tell her stories about the fictional Land-of-Almost-Awake, and these stories corresponded to other characters and things that were happening in the overarching storyline. It was an interesting and engaging technique that I thought added to the overall charm of the book—which, to repeat, was completely off the charts.

Here’s a snippet of the book’s opening:

Every seven-year-old deserves a superhero. That’s just how it is. Anyone who doesn’t agree needs their head examined.

That’s why Elsa’s granny says, at least.

Elsa is seven, going on eight. She knows she isn’t especially good at being seven. She knows she’s different. Her headmaster says she needs to “fall into line” in order to achieve” a better fit with her peers.” Other adults describe her as “very grown-up for her age.” Elsa knows this is just another way of saying “massively annoying for her age,” because they only tend to say this when she corrects them for mispronouncing “deja vu” or not being able to tell the difference between “me” and “I” at the end of a sentence. Smartasses usually can’t, hence the “grown-up for her age” comment, generally said with a strained smile at her parents. As if she has a mental impairment, as if Elsa has shown them up by not being totally thick just because she’s seven. And that’s why she doesn’t have any friends except Granny. Because all the other seven-year-olds in her school are as idiotic as seven-year-olds tend to be, but Elsa is different.

I love this so much I want to go read it again.

And maybe I will.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

I used to care a whole lot about the way my boys dressed. I would doll them up for family pictures and make sure their hair was just right or, if they’d slept on it wrong, I’d toss a really cute hat on top of the mess. I worked hard to make sure they had matching shoes—not just shoes of the same color and style but shoes that actually matched their outfits and complemented each other. I matched their socks and sometimes even their underwear.

No, I never went that far, because half the time my boys weren’t wearing underwear in the first place.

When I look back at all these early family pictures, which depict our stylishness and prove that I was not always dressed in workout clothes, I miss them a little. Husband and I made it look like we actually had it together. I’d like to look like I have it together every now and then.

But then I think about how much time it takes to get boys to actually care about the way they look, and I think, nah, it’s not worth the effort.

I have friends who are newer parents than Husband and me, because we started a little early, and these parents spike up their kids’ hair and dress them all cute for every single circumstance you can imagine, and when I see those cute little boys dressed by their parents, I think to myself that they’ll give it up in a few years, too. Eight years of parenting and all the battles and challenges that come with it have made me something akin to apathetic when it comes to what my kids wear. Now I’m just glad they walk out the door wearing matching shoes—and half the time one 4-year-old can’t even manage that, which he’ll point out to every teacher in the kindergarten hallway as we drop his older brother off at school.

This morning, on the way to school, this particular child, who is a twin, wore one flip flop and one tennis shoe—not because he couldn’t find the matching shoes but because he wanted to. The 7-year-old wore shoes that his two biggest toes poked through, even though he has perfectly fine tennis shoes that don’t have holes at all. When I pointed this out, because I didn’t want his teacher to think that we’re in such a bad state that we can’t get him adequate shoes, he said he preferred these shoes, because they left a little breathing room for his feet. I said, fine, do whatever you want, but don’t call me when the soles fall off.

It flapped all the way to school.

Occasionally I marvel at this strange person I have become. The person I used to be would never, ever have agreed to let her child, essentially a representation of herself, walk outside the house like that. Now I feel perfectly fine allowing a boy to walk out the door in a navy blue and cerulean striped shirt with bright green pants that have gaping holes in the knees, because there are much more important battles I will have to fight during the day. I don’t care if a kid goes to school in two left shoes. I don’t care if a kid woke up with Einstein hair that they didn’t even try to comb. I don’t care if they wear shorts on a 30-degree day. They are in charge of their own wardrobe.

Full disclosure, I do still make an effort for family pictures. We’re paying for those things, and I don’t want them to go down in history as proof that we were drowning beneath waters of our own making.

For the everyday, no family pictures dressing, my kids look like feral felines who thought they’d take a stab at wearing clothes. I try not to let it bother me. Every now and then I have to draw a line. My 5-year-old has this workout shirt that’s a pretty blue color. It looks really good on him with his naturally tan skin, but he has worn it so often that now it looks like it’s been dragged through a pile of mud even after I’ve scrubbed it with dish soap (which is my eco-friendly solution for stain remover) and washed it. There are stains on this shirt that will never come out. So when he puts it on, I always tell him to change. He can wear it around the house, but not to church or school.

The other day, Husband attempted a talk with the 9-year-old about the proper dress for church, because we’ve gotten a little lax about the appropriate attire now that we’re working for one that requires extensive travel on Sunday mornings and we have to get up early.

Husband: From now on, you need to wear shoes to church, not flip flops.

9-year-old: Okay.

Husband: And also no sweat pants with holes in them.

9-year-old: Okay. And I should probably also wear underwear.

Well, yes, that would be nice.

But, you see, these are the kinds of things that I’ve stopped caring so much about. Because there are so many other things to care about. Like their hearts and how they feel about what happened at school today and whether there are any concerns that they have about friends or bullies. I don’t have the time or energy to spend my days caring about what they look like when they walk out of the house. Soon enough, they’ll all care about the way they look, and then we’ll never find our way back to that innocent time of early childhood when they thought that sweat pants paired with a button-up shirt qualified as dressing up. And I don’t think I’m quite ready to leave that time yet, because leaving it will be an arriving of sorts. They get to remain children as long as they don’t care about what they look like, but as soon as they start caring what they look like, they become young men. I want to enjoy the childhood. So I’ve loosened my grip on this.

If they want to look like a fashion experiment gone wrong, so be it. After all, most days I look like I just finished at the gym. In fact, to most of the parents at my boys’ school, I probably look like I do nothing else but spend time at the gym.

Well, except for the few extra pounds I carry around.

This is an excerpt from This Life With Boys, the third book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

So much of what I do, as a mother, goes unseen. I plan our healthy meals and read the labels of everything I put in my shopping cart, to make sure our home stays toxin-free, and I mix our own cleaners and make note of when we’ll need to reorder those essential oils we use for healing. I carve out a schedule that protects our family playing time, and I craft a budget that means we have food and shelter for another month, and I make sure all the art supplies stay stocked.

I manage Amazon subscriptions for ingredient-approved vitamins and count them out every single day and line them up next to my boys’ breakfast plates, and instead of “thank you” I hear about how they didn’t want these scrambled eggs this morning because all their friends get to eat cereal for breakfast, and why can’t they? I clear out their closets when their old clothes are too small, and I buy them new underwear when the old ones cut off circulation and I stock new socks when the old ones have too many holes, and the only thing I hear for it is how they wanted red socks instead of the black ones I bought.

I turn off lights and flush toilets and mend their blankets and remind them to brush their teeth and find their lost library books and read stories until my throat hurts and send them back to bed a thousand times every single night, and I don’t even think they notice.

There are so many days I can feel downright invisible.

Welcome to being a mother.

///

When I was eleven years old, my mom slapped a magnet dry-erase calendar on the front of our white refrigerator.

“Dish schedule,” she said.

Our names were written on it in black—Jarrod, Rachel, Ashley, and Mom switching places on all the squares. Every month she sat down with a school calendar and the dry-erase one and wrote our names on the schedule in a way that wouldn’t interfere with our lives.

The schedule got more complicated when we got to high school, because there were volleyball games and every-night-of-the-week practices and football games with the marching band and National Honor Society and Wednesday night church and homework after all that.

I didn’t appreciate all the hard work that went into a schedule as complicated as that. All I did was resent that I had to wash dishes two nights a week. I resented that I worked so hard at school all day and then slaved away at volleyball practice and rode a bus to the pick-up point and finally got home after dark to finish what homework I couldn’t do on the bus, because I cared about handwriting and the bus was too bouncy, and then I still had to do the dishes.

So unfair.

My tunnel vision didn’t let me see that she worked all day, much harder than I ever did at school, and then she cooked dinner and tried to keep it warm for me and drove to meet the bus and stayed near while I finished my homework so I’d have help if I needed it and, on top of all that, she planned meals for the month and did all the shopping and budgeted our very limited resources and wrote out a schedule for doing dishes so one person was not overburdened with the responsibility.

She was a mother.

She was invisible, too.

///

Now that I have children of my own, I know just how selfish children can be. I know just how thankless motherhood is. I know how no matter what we do behind the scenes, there is still more they want us to do.

It’s simply the nature of children. I know this. They don’t see their own selfishness or the way those ill-timed complaints can make a mama not ever want to cook a hot breakfast for them ever again or how the mere thought of tackling eight loads of laundry that come back every week is enough to keep her in bed when the alarm chimes. They only wonder why they’re having oatmeal again when today was supposed to be pancake-day. They don’t see that Mama ran out of time to flip pancakes because she had to turn every male shirt right-side out before sorting it into laundry piles she’ll spend all day washing.

It’s completely, developmentally normal for them to not make those connections yet. Someday they will.

But someday means nothing for this day, this day I stripped all his sheets and blankets and spent half the day he was at school vacuuming and washing and putting a bed back together because he woke up with ant bites all over his legs and I’m afraid there might be ants in his bed because they were eating popcorn up here yesterday even though it’s against the rules. This day he comes out of his room complaining that his blanket is still a little wet.

This day when I loaded the washer with that first pile holding his Spider-Man shirt, because I was sure he’d want to wear it on his birthday, and there’s just enough time to wash and dry it before he has to leave for school. This day he comes down the stairs crying about how he can’t find his workout clothes to wear on his birthday, and I know they’re lying at the bottom of another pile I planned to wash later today.

This day I woke up to find three lights left on all night and I can’t help but mentally calculate how much that’s going to cost me.

The promise of someday does not make this day any easier.

///

After I married and had an apartment of my own, my mom came visiting with a box.

“What’s that?” I said, because I had recently finished unpacking, and I hadn’t missed anything important.

“All your old stories,” she said.

“What stories?” I said.

“The ones you wrote when you were little,” she said, and she pulled out one that imagined what I would do if I had a million dollars. I’d written it when I was seven.

“I’d buy a car, and I wouldn’t share with my brother,” I’d written. We laughed about it.

There were Little House on the Prairie imitations and the story about a girl miraculously walking again to save her friends from danger and another scrawled out on notebook paper the summer I went to visit my dad.

“I didn’t know you kept all these,” I said.

My mom smiled. “Of course I did.”

Of course she did. They were pieces of me she loved. They were pieces that proved her love.

And she is a mother.

///

There is a drawer in my closet where I keep my kids’ drawings and old writing notebooks they’ve filled with words and loose papers with quirky doodles filling corners. My boys don’t know the drawer is there.

My eight-year-old doesn’t know that when he slipped his note under our bedroom door, the one that bears a picture of a boy with a red face and smoke coming out of his ears and the words, “I feel angry when you tell me it’s bedtime,” the note went into that drawer. My six-year-old doesn’t know that when he wrote a kindergarten essay in school about how he knows his mom loves him when she reads to him, his essay went into that drawer. My four-year-old doesn’t know that when the amazing fox picture he drew disappeared from his drawing binder it went into that drawer.

They don’t know all the ways I love them, because they are still young children who believe love looks mostly like hugs and kisses and sweet snuggles. They don’t know yet that it actually looks like time and service and invisibility.

What I am still learning in my mother journey is that sometimes the greatest acts of love are the ones that whisper instead of shout.

A storage container with writing treasures shoved under our mom’s bed.

A dish schedule that honored our time over her own.

A ride to early-morning volleyball practices, even though she worked late.

I want to be that kind of great.

Indignation comes welling up in me, every now and then, when I’m tired and frustrated and annoyed that I can’t seem to find a single minute to myself. I want to be noticed. Acknowledged. Appreciated. I forget that invisibility is better than alone.

I get to be a mama. I get to love my children through olive oil brushed over broccoli and a sprinkling of sea salt sitting on top. I get to love them by joining them at the table and coloring a picture of Lightning McQueen, even though a thousand other responsibilities are calling my name. I get to love them with a secret drawer that holds treasures more valuable than what sits in our bank account.

I get to be loved by his bursting into the room while I’m working so he can give me a missed-you kiss. I get to be loved by the flower he brings me, because its beauty reminded him of me, and I get to watch it curl up while I’m writing. I get to be loved in his request to be carried downstairs, just like old times, even though he’s so much heavier now and, also, fully capable of walking himself.

I get to be loved in a million silent ways, and I get to love in a million silent ways.

Welcome to being a mother.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash)

Leaving 1

What I couldn’t wait to leave behind:

Old boyfriends

Mom checking in about everything

My sister always around, leaving my curling iron on

Food

My brother’s loud music

A kitchen full of strawberries

A house that felt suffocating

A room with rust-colored carpet

Open fields

The small-town community

Endless questions

What I would miss:

Nothing

Leaving 2

What I actually missed:

Everything

This is an excerpt from The Summer of My Discontent. Visit my Reader Library page, where you can get it and a couple of volumes for free.

(Photo by Devon Janse van Rensburg on Unsplash)

My boys absolutely love graphic novels. So when I discovered Raina Telgemeier and her wonderful graphic novels, I knew I needed to introduce my boys to her. Every single time we go to the library, they now come home with at least one Telgemeier book, even though they’ve already read them all. Multiple times.

A good friend of mine had the opportunity to see Telgemeier in person and mailed us a fabulous autographed copy of Smile, which my boys thought was the coolest thing. They took turns taking it to school and showing it off to their friends.

I love that Telgemeier gets them reading.

Smile is a story about a girl who learns to love herself.

Here are three things I liked most about it:

Overall, this was a fantastic read, and I’m glad my boys are reading and re-reading it, because it’s a message that needs to sink deep: Love yourself, as you are.

Mother’s Day is one of those days when everyone is thinking about Mom—the kids are still in school and make her all sorts of gifts during class, Sunday school teachers help kids trace their hands and use each finger to tell Mom why she’s so special, the stores put their best flowers and chocolates on display.

In short, moms get a lot of gifts for Mother’s Day. Some are more keepable than others.

Here are some of the wildcard gifts I’ve gotten on Mother’s Day:

1. Info sheets

These are, of course, hit or miss, depending on the kid. One kid will say my age is 16, one will say I’m 5, and another will say I’m 120. It’s the same with the details—you can tell which kids are paying attention and which kids are completely stuck in the World of Me, Me, Me. The kid who wrote that my favorite thing to do in the whole world is the dishes must not be listening to all the complaints I air every night at 6:30 p.m. Either that or I must look really happy doing those dishes (I can’t fathom how this could be).

2. Pieces of kid-made art

These are also hit or miss. One year one son came home with a delightful flower pot that, unfortunately, faded when I set it on the window sill but which was still lovely, years later (I still have it). Another son once came home with a clay cupcake he’d painted to look incredibly appealing (except that the icing was green—artistic liberties). I have it sitting on my work desk so that every time I look at it I can crave cupcakes.

Another son recently came home with a portrait of me—which was actually quite frightening. That went in a drawer.

3. Old used things

One of my sons once gave me a toothbrush that had been used. I could tell because there was a collection of dried toothpaste hanging out between the bristles.

They’ve also given me stuffed animals they took back at bedtime, half-eaten cookies, and old toys they found buried out in the yard.

It’s the thought that counts.

4. Wildflowers

These are some of my favorite gifts, because my sons collect wildflowers without anyone suggesting it or overseeing it. They simply gather the flowers, stick them in a cup, and thrust them in my face. Even if I get splashed with wildflower water, this gift is the best.

5. Time to myself

Of course what every mom really wants for Mother’s Day is time to herself. This can’t happen without the support of a partner or friend. A few years ago, Husband left me a note on Mother’s Day. It said, “Hey, I thought you might like a Sunday off leading worship, and since it’s Mother’s Day I figured today would be best.”

Sweet, right? The note also said, “I left the kids at home so you could spend some quality time with them.”

He never did it again after I re-gifted that one for Father’s Day.

I have a whole bin of all the terrible gifts my kids have given me on Mother’s Day—because no matter how awful they are, it’s still nice to know your kids appreciate you.

And I can always sneak that well-loved bunny back in bed with him once he falls asleep and take, instead, the memory of his angelic face.

(Photo by Vesela Vaclavikova on Unsplash)

The other night, my husband and I watched Dead Poet’s Society, a movie I remember loving in high school. I loved it just as much this time around. It is a phenomenal movie with phenomenal writing and acting.

But.

It struck me differently this time around. I’m a parent now. I cried—no, I sobbed—great, heaving sobs—when a boy is so beat down by the box his parents put him in—telling him who they expect him to be, what his career choice will be, what he absolutely cannot do, which happens to be his passion—that he has little freedom to enjoy his life and be who he is. He feels stuck in a future of his parents’ making, and it holds nothing he wants or needs.

As a parent, I cannot see this movie without feeling the weight of this responsibility: to let my children be who they are, not who I want them to be.

It’s one of the most important things in the world. It’s the way we show them love. It’s how we teach them to be themselves—and not anybody else’s definition of who they should be.

We all maneuver through a time when the thoughts and opinions of other people mean something to us, whether those “other people” are our parents or our friends or our spouses or our brothers and sisters. Maybe those thoughts and opinions will always mean something to us, because we’re relational people.

But oh!—we should never, ever let them limit us.

When I was in college, I was. 4.0 student, but I got a B in my first creative writing class. In fact, my professor so disliked my poetry (he called it florid and melodramatic) that he scrawled on one of my assignments something along the lines of, “Probably not a future for you here. Meaning, in poetry.” He said pretty much the same about my fiction (he was not a nice person).

On Sept. 18, 2018, The Colors of the Rain, a novel written entirely in poetry, will be published by a reputable New York publishing house.

Maybe I’ll send him a copy.

I let his words stifle me for a while. I put down my fiction pen and picked up my journalism one. I wouldn’t change that choice, knowing what I know today, but I would change the way I let him bully me out of my dream, which was always to be a poet and a novelist. I thought, then, that the things people said about me defined me. They knew more about me than I did, I believed. They could see things I couldn’t. They were right.

They didn’t, they couldn’t, and they weren’t.

“They” can’t say what you get to be or who you are or even why you were put here on this earth. We aren’t made for someone else’s box. We are made for something far greater: our purpose. And only we can know that.

I have been called many things in my life, some of them unthinkable, some of them moderately annoying—for writing what I write, for choosing to have six children, for speaking out against judgment and hate.

I have never let these dishonorable, sometimes vile, always highly inaccurate names define me, impede my vision, or silence me from speaking what I must speak.

Neither should you.

Be your wondrous, brave, spectacular self. This day and every day.

(Photo by Daniel Cheung on Unsplash)

8:07:03

Five minutes of not

paying attention and they’re

tearing up the house.

8:07:12

Two minutes after

they sit down with a toy they’re

done. It’s exhausting.

8:07:15

If they would listen

to instructions, life would be

easier for them.

8:07:16

If they would listen

to instructions, life would be

easier for me.

8:07:18

This is not the way

a mother is supposed to

think; but she does, still.

8:07:22

It’s okay; I’m not

a bad mom for acknowledging

that twins are hard.

8:07:23

They are hard; that doesn’t

change my love for them—it

is fierce, motherly.

These are excerpts from The Book of Uncommon Hours, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by Helen Montoya Photography.)

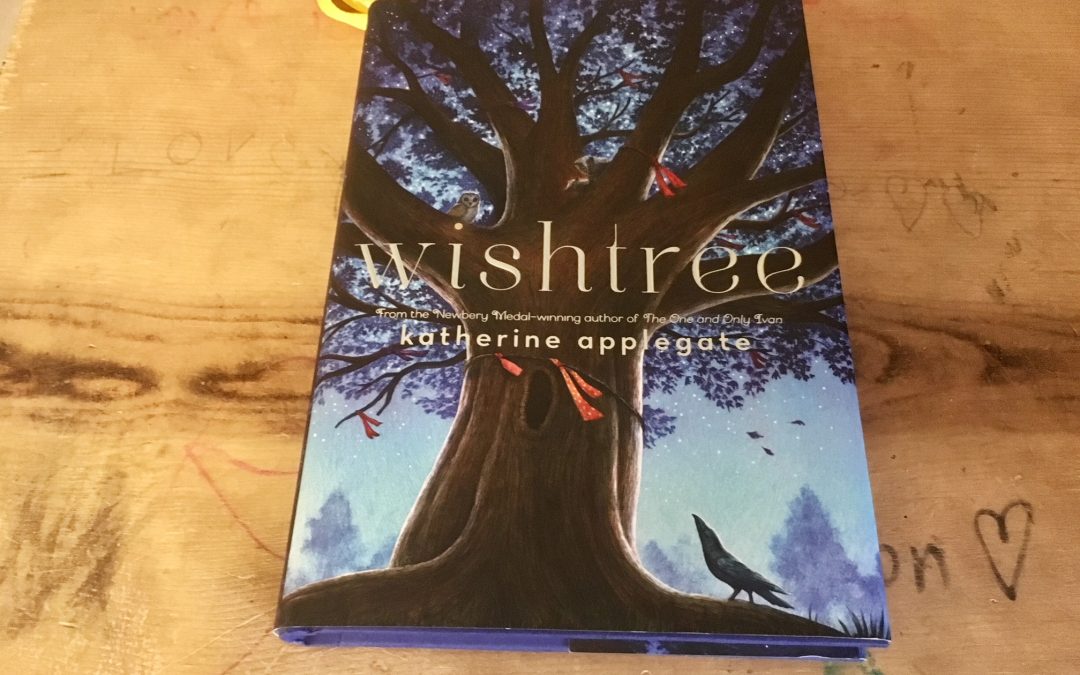

I have been reading Katherine Applegate for a long time. When kids ask me who my favorite author is, she is one of the authors I list (because how does a person pick only one?). And her newest book, Wishtree, is no exception to the line of other heartwarming, beautiful books.

Wishtree is a story about wishes and love and hope—all the things I expect from one of Applegate’s stories.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it.

The interesting point of view. The book was told from the perspective of a tree, which was unique and quite lovely. The tree observed many different things and was almost a silent witness to the things that went on in the world. Red, the wishtree, could only talk about what happened outside of doors, since the tree was rooted in place. It was an interesting limitation that Applegate executed masterfully.

The tension. It might seem difficult to tell a story from the perspective of a tree, because how much can a tree really witness enough to fill the pages of a story? Well, it turns out a tree knows a lot. There were two storylines in this book that lent tension to the story, and they were both sweetly beautiful.

The characters. I’m not just talking about Red, the wishtree, or the children Red saw on their way to school; the story also contained a cast of animal characters that had very distinct personalities and sometimes brought a little humor to the story as well.

Wishtree was a delightful book for kids of all ages. I’m looking forward to reading this one with my boys—aloud, of course. Applegate’s stories always beg to be read aloud, one of my favorite things about them.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.