by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

I was not a physical child. Some might say this is most likely because I was a girl, but I also didn’t get angry all that often—at least not angry enough to hit. I do remember hitting my sister once and only once, when we were teenagers and she said something that really enraged me. I think it had been piling for a while. She stole one of my shirts, messed it up, and tried to hide it from me. It was something really important like that.

It’s an entirely different story with my boys. My boys can pick a fight and finish it before I can even get the words, “We touch each other gently” out of my mouth. One minute one of them is complaining about how his brother stole a piece of his puzzle, and the next minute the words are knocked out of his mouth by an errant smack (not by me. I don’t hit my kids. Neither does Husband. That shows us that this is something that is born inside them.). Of course they get in trouble for this. Of course they have to make amends when they’re ready (I don’t like insincere amends). Of course there are consequences intended to keep them from doing it again. But it never works.

I’ve heard stories from other parents of boys who say that their kids, even when they were teenagers, didn’t get over this physical part of their nature. Husband tells me a story from his childhood wherein his parents weren’t home and he and his brother, 15 and 13, respectively, started fist-fighting because they could not agree on something also really important, like who left the light on. Husband punched his brother, and his brother started crying and writhing on the floor like it really hurt, but when Husband came close to make sure his brother was really okay, his brother punched him right in the face. Husband responded by locking his brother outside the house and not letting him in no matter what or how loud or how long he screamed. This is a lovely thing to look forward to.

For the life of me, I can’t understand this immediate physical response. When I feel angry, I don’t see a wall and think, I should hit that. I might see the wall and think that I would like to hit it because I feel so angry inside that hitting might make me feel better. But then there’s this complicated thought process that happens after that initial observation, and I’m suddenly thinking about how much it would hurt to hit a wall and how I’d most likely break something, and I really don’t want to break something, because I need my hands for writing and for playing the bass guitar and for picking up my youngest son, and then I start thinking about what I would possibly do if I broke my hand, and the answer is, I would go a little crazy, because things would pretty much fall apart in a home like ours. One parent down is like claiming defeat before the battle has even begun. How would I cook? How would I do my workout? How would I keep the boys out of anything, when I would have only one hand and already need fifteen? So the thought, I should hit a wall, never results in an action.

The problem is that boys don’t have this complicated thought process. They just receive the thought, I should hit that, and they do it. I know, because the 9-year-old has done it before. He’s hit a cabinet or a table or something else—more than once, I should add—and every time he crumples up like his hand is undergoing the worst pain imaginable. Tell me why you would do this again. He always regrets it.

I also know this because Husband punched a wall when a picture dropped down and cut the top of his skull, and the nerve of something this ridiculous happening sent him over the edge for a brief moment in time. He put a hole in the dining room wall.

I know, too, because the 6-year-old, who is one of the kindest children you will ever meet in your life, has hit his little brothers when they destroyed his writing journal and he couldn’t make sense of the masterful pages after they got finished with it.

Boys hit. They don’t think.

We’ve tried to create a system that will help them think before they do anything. Emotions are tough, and the moments of emotional flood are even tougher. We have reminders for them to breathe. We have consequences. We have rewards.

I’m beginning to think that systems don’t work.

When our boys hit one another, they’ll do their brother’s chores to make up for it—washing the dishes, taking out the trash, cleaning up the toys they were playing with alone instead of together. They will be required to write a kind note to their wounded brother. They will be expected to complete their retribution—sincerely.

And yet often I wonder if there is something within them that is simply wired to be physical. Brain science hints that there is, of course. But even if brain science wasn’t around to suggest this, one could take a look at a boy’s play pattern. My boys will regularly roll on the ground and wrestle each other until someone is crying in mercy. They enjoy standing up at the top of our stairs while Husband throws heavy couch pillows at them and tries to knock them down. They think it’s fun to engage in a slap-fight.

One time, when we lingered a little longer than usual at the library playground, our boys were playing with some other boys they’d found somewhere around the slides. The 9-year-old hurtled past me, screaming for his life. I thought he might be hurt, so I followed him. It was not easy to catch him, but I eventually did.

“Hey,” I said. “Are you okay? I couldn’t tell if you were upset or happy.”

“We’re playing a game,” he said and made as though to move off again. I grabbed his arm.

“What kind of game?” I said.

“A hitting game,” he said.

“What?” I said. “Why would you want to play a hitting game?”

“Because it’s fun,” he said.

“That is not my definition of fun,” I said.

He laughed and said, “That’s because you’re a girl, Mama.” And he ran off.

On the way home, I listened to the chatter in the back seat. All three of my older boys miraculously agreed on something: They couldn’t wait to play the Hit Until You Cry game again.

This is an excerpt from This Life With Boys, the third book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

My youngest son, who just turned 3, has been a little clingy lately, waking up with night terrors, begging to sleep with us. He follows me around the house like he doesn’t want to let me out of his sight, like he’s afraid to be alone. Something has frightened him—it’s unclear what; he does not have the language to explain this fear. Not many young children do.

His clinging sometimes feels a bit suffocating.

For Christmas this year, he got some cute dinosaur slippers. He wears them everywhere—around the house, on the walk to school, to the store. People comment on how adorable they are—and they’re right.

The other day, he crashed into my room, where I was working. I said a quick hello and then I went back to work, fully engaged in writing whatever story I had open in front of me. And a few minutes later, I looked up to see him typing away at my grandmother’s old Remington.

In his dinosaur slippers.

I watched, blinking away tears I couldn’t explain. He’s growing up, he’ll soon get over his clinginess, he will not fit into these dinosaur slippers forever.

I made a note to myself: Don’t miss the moments.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

The petals fall:

the wind twirls them toward blades

that bend and straighten,

a world off-center

It is a hatchet:

information, unwanted

It will change everything

a future unmade

And yet:

in the hollowed out, exhumed earth

a seed opens, a bloom unfolds

a brilliant reminder

Life unmakes

and remakes

in quick succession

(Photo by Debby Hudson on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

As a former journalist, I enjoy reading creative nonfiction books, especially by incredible journalists like Erik Larson. I’ve read many of Larson’s books, and the latest of these was In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin.

It was just as fascinating as it sounds.

In the Garden of Beasts takes place in the time period before World War II, when William E. Dodd became America’s first ambassador to Germany, where he and his family watched Hitler create Nazi Germany.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about this book:

- The history: It was fascinating getting to know this part of the history that you don’t hear about, and it reminded me that there are always stories running beneath the surface of things that we don’t even know about until someone shines a light on it all. Larson shone a very large light.

- The characterization: One of the reasons I love Larson is that he has a wonderful ability to characterize people based on research and letters. He talked about his process for putting these character studies together—he scoured diaries, newspaper articles, and other historic materials to bring the characters to life. I appreciate his thoroughness in creating a story that is believable, entertaining, and historically accurate.

- The reportage: I’ve always been drawn to true stories, and Larson has a knack for digging so deeply into something that he feels comfortable telling a true story that is good—no, more than good: riveting. He uses humor, shock, delight—every range of human emotion so the story comes alive. It was a wonderful book.

I’ve got a few more Larson books to read before his entire backlist has been consumed. I’m looking forward to diving into more.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

April Fools’ Day is always a fun time in our home. I live with a bunch of pranksters, which means they keep me on my toes all day. No one is safe this day—not even Mama.

Every year, I painstakingly contemplate what kind of tricks I’d like to play on my kids. Here are some I considered this year:

1. Steal their underwear.

I imagine this prank would go something like this:

Me: Are you missing anything today?

Him: No.

Me: Nothing?

Him: No.

Me: How long has it been since you changed your underwear?

Him: I don’t know.

I doubt he (and by he, I mean any one of my kids, take your pick) would even notice, without my explaining to him what I’d done, so I skipped this one. Maybe in a couple of years, when he actually cares about how he smells.

2. Hide their shoes in random places.

The problem with this little idea is that my kids don’t really need any help with losing their shoes. They leave them in odd places and accomplish this little trick on their own—every morning, without fail.

3. Stuff all their socks inside one lucky sock.

One of the 5-year-olds does this on a regular basis, so I don’t think they would really appreciate my work on this one. Why waste all that time?

When I asked them what they use this monster sock for, they said “Hitting each other.” Of course. They call it a sock bomb.

4. Pretend the hot water got turned off for the one who actually cares about taking a shower.

I feel like that would discourage him from taking a shower, though, and we definitely don’t need that. Boys aren’t exactly the most hygienic people around.

5. Turn all their clothes inside out.

Oh, wait. This happens every laundry day, because that’s how they put it in the dirty clothes hampers, and I don’t have time to turn it all the right way.

6. Replace their morning milk with buttermilk.

My dad did this to me when I was 6. How many people can remember memories from when they were 6?

Exactly. It was traumatic. I took this one off the table.

7. Tell them they don’t have school today.

This would have been really fun, except that April Fools’ Day was on a Sunday. Also, I imagine that when the day falls on a school day and if I actually executed this prank, there would be some messy cleanup when they find out it’s a joke. And by messy cleanup, I mean lots and lots and lots of whining.

8. Tell them it’s “dress like a Dr. Seuss character” at church today.

This one I actually managed. I wish I had a picture to show you, but I was too busy laughing.

I’m glad we can have a house that embraces pranks.

But now that I can’t find my left running shoe and there’s a stick-bouquet hiding under my covers and someone switched out my favorite soap with hand sanitizer, I’ve realized that I’m really good at dishing it out—but not so great at taking it.

Mom was right all along. Imagine that.

(Photo by Charles Deluvio 🇵🇭🇨🇦 on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Just a few days ago, I got a precious letter from a reader, thanking me for one of my essays. She found it because she was looking, because she’d just lost two babies, twins, and she needed some comfort.

I have written many versions of this story, about the daughter who died before I could meet her, because writing is my way of working through something hard and unthinkable and tragic. Writing is my way of finding my feet again.

The day they wheeled me into the operating room, where they sucked a dead baby from my uterus in the same way they take live ones from the women who don’t want them, I wrote the pain onto my phone until the anesthesia knocked me out. And then I started writing again as soon as I woke, when the agony of an empty womb ran red and bled through my fog.

I wrote in all the days after. All the months after. All the years after.

And now, three years later, there is a woman searching for comfort, and she finds my words, and she feels less alone in her sorrow, even though we are thousands of miles apart.

We count it all joy.

We count it all joy that a day as sorrowful as that one could do this: Heal another heart, or at least some small piece of it.

///

The year I turned eleven a letter came in the mail for my mother. It told her secrets she had known for years but didn’t dare believe, because even in the humiliation, even in the shame, even in the disappointment, she still loved.

The letter told a story of a man and a woman and a child and a baby on the way. It told the truth of heartache and betrayal. It told the future of a single mother.

She didn’t feel brave enough to become what the letter said she must, but she did. She filed for divorce and bought a house with the last of her savings and got a second job so she could raise her kids on her own.

It wasn’t all neat and pretty, because she was lonely and heartsick and sad, and sometimes it was near impossible to see a way out of the mess. But she put one foot in front of the other and marched on, like a heroic woman warrior, because she had three kids who needed food and shelter and both a mother and a father—and she would play the father for a time.

There came a woman, years later, who visited her Sunday school class, who broke into tears when the leader asked for prayer requests, who could barely say what she needed to say about leaving a husband and two kids to feed and not really knowing how or if she would make it on her own.

And my remarkable mother knew the answer to this woman’s wondering.

Yes, she said. Yes, you can make it. And here is how.

The real miracle of it is that my mother, in comforting another woman who had lived the same story, found her way fully into forgiveness.

We count it all joy.

///

It’s not easy, this counting it all joy—because there is a baby who died, and there is a husband who is husband no longer, and how can this dark night turn to sun-bright day?

Maybe it’s hard to see from the suffering side of it, that our pain will one day, months or years or decades from now, be used to comfort another ripped-in-two heart. Maybe it doesn’t seem fair that we would have to endure death and divorce and abandonment and shame and disappointment and fear and pain and anxiety and heartbreak so that one day down the road we can walk someone else through their own.

Maybe we wouldn’t choose it for ourselves, not in a million years.

But all those maybes don’t change the truth: that our sorrow places, those chasms cut with knives that plunge deep, are the very places we can be filled with the deepest joy. Of course it’s hard, and of course it’s unwanted, and of course we would never dream of asking for the opportunity to suffer, but this is life and this is unfair and this is what happens when we choose to risk and love and live.

In the sorrow places we learn how to live with our hearts wide open. Our lives wide open. Our selves wide open.

We learn how to count it all joy.

///

When my third son was born, our pediatrician, an amazing, empathic man, breezed into the room and shook my husband’s hand, pulling him into an embrace, because he was, genuinely, so excited that another Toalson boy had slipped into the world. And then, when the congratulations were done, he took out his devices to look over the baby.

The air in the room shifted when he listened to my boy’s heart. He tried to act like it wasn’t a big deal, but I could see the alarm in his eyes.

“It sounds like there’s a murmur,” he said, and he looked at my husband, not me, because he knew, he knew what those words would do to me. “It’s probably just one of the valves that hasn’t closed up yet. Sometimes that happens. It’ll likely correct itself.” He put his devices away and then said, like an afterthought, “Come see me in another week so we can make sure.”

It didn’t correct itself.

He referred us to a specialist, and it was two weeks of dreaming about a boy whose lips turned blue while I watched and there was absolutely nothing I could do about it. Two weeks of agony, waiting for that appointment, waiting for someone to tell me if something was wrong with my baby boy’s heart.

I would put my older boys down for their nap, and I would hold my newborn while I should have been sleeping, because sleep was the least important thing in the world if I had to say goodbye. I would pull him into bed with me at night, because I was so afraid it would be the last night. I would cook dinner, holding him in my arms, my tears dropping into the chicken noodle soup.

And then, finally, finally, finally, came the appointment. I took my infant into the room while my husband stayed with our other two sons in the decked-out waiting room full of toys. This was a heart doctor for children with heart defects. The waiting room was amazingly entertaining.

I sat beside the doctor and her assistant, who was there to hold down the babies who decided they didn’t want to do an echocardiogram. She warned me I might have to help hold him down, but my boy slept right through it.

He slept through a doctor pointing out all the perfection, running her finger along the lines of arteries that pumped and pulled blood. He slept through a mama sobbing because of the incredible, miraculous beating of a tiny little heart, pulsing on a screen, lighting up with red and blue, the colors of life. He slept through a mama sobbing harder, if possible, when the doctor said, “Perfectly healthy. Nothing to worry about here.”

“I’m sorry,” I kept saying. “I’m sorry. It’s just…”

I couldn’t even find the words for something so big and yet so small, but the doctor understood. Of course she did. She sees it all the time, these tiny veins and tiny organs and tiny perfection pieces keeping a baby alive. She patted me on the arm and sent me out the door with the words, “Go enjoy your healthy baby boy.”

And I did.

A year later, a friend’s daughter was born with what doctors suspected was a murmur. I knew what it was like. I knew the agony of waiting and the torture of anxiety and the way worry can take a whole birthing day and wring the life right out of it.

So I shared my story. I let her know she was not alone in her fear, that someone else had walked her shoes, that she was not forgotten or unseen but known in her suffering.

We count it all joy.

///

There is a catch here, too. Of course there is.

We can suffer in silence. We can crawl into our shells and pretend life is grand and we have not a care in the world, and we can show them that worry and anxiety and suffering do not touch us.

We can grieve secretly, alone, in our closed-off places.

It’s more comfortable there, because our shells are thick and dark and hidden, and “they” don’t have to know that we questioned the purpose of life when our baby died, and “they” don’t have to know that we worried we would not make it as a single mom of three kids, and “they” don’t have to know that we doubted the very existence of God in the moments we thought our boy could die.

Or we can set those secrets free. We can let our sorrow loose to light up the world, transform it completely. The beautiful piece of sorrow is that the darker it looks on this side of it, the brighter it turns on the got-through-it side.

How do we let loose our sorrow?

We share. We tell our stories. We carry on.

We’re not the first or the last to walk through this specific sorrow space, but it is only in our sharing that we see clearly that we are never alone. That we can bear each other’s burdens. That we can heal, together.

That we can count it all joy.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Maria Shanina on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

7:12:58

The sound of whine is

like a blue whale obliterating

my last nerve.

7.12.59

(He’s whining about

his shoes, which he says are too

loose on his right foot.)

7:13:01

(He’s whining about

how he never gets to ride

his scooter to school.)

7:13:04

(He’s whining about

how he didn’t win the foot

race with his brothers.)

7:13:18

Supermom today

looks like leaving half of them

behind for the walk.

These are excerpts from The Book of Uncommon Hours, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by rawpixel.com on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

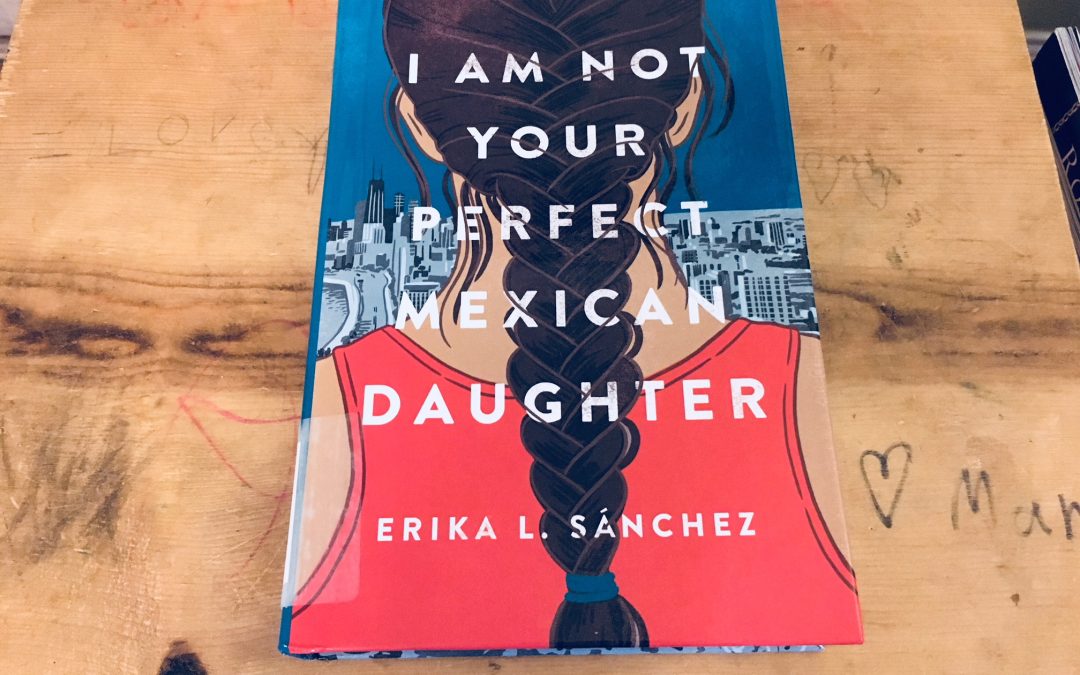

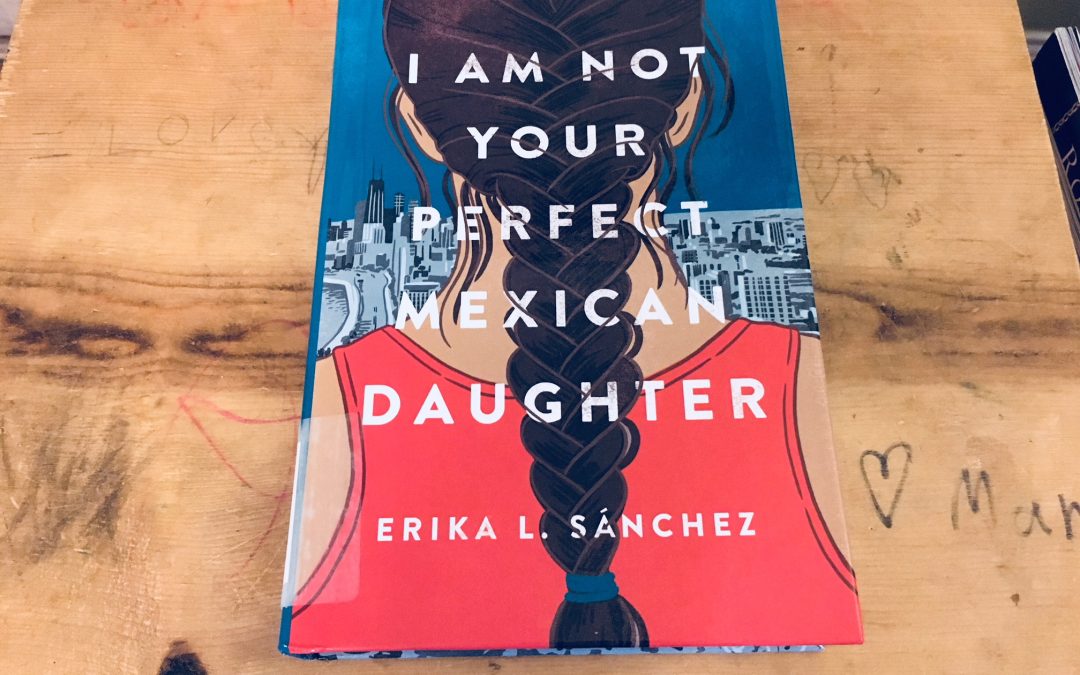

The book I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, by Erika L. Sánchez, has been on my to-read list for a while. I finally got around to reading it last week, and wow! What a book!

I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter is a young adult literary novel about immigration, depression, family, and believing that something better is possible.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

- The personality. Julia was a fun person to get to know. She wanted more than her parents’ immigrant life, and sometimes that set her at odds with them, but she was a persistent person. She was also the kind of person who was unafraid of hard work; she wanted what she wanted and she was going to work hard to get it. I loved this about her.

- The glimpse into another culture. There was a quinceañera and all the other aspects of the Mexican life that Julia and her family brought to America. Some of my favorite moments of the story were when her parents would talk about Americans; it was great seeing how other cultures look at the United States—always a humbling thing.

- The teenager issues. This book touched on quite a few issues, in a sort of surface-level way, some that many teenagers will face in their lives and others that were unique to Julia because of her culture. There was suicide, sex, depression, the drug cartels in Mexico, abortion, and homosexuality. I enjoyed reading about how a teenager responded to them.

Here’s the opening, which hooks the reader immediately:

“What’s surprised me most about seeing my sister dead is the lingering smirk on her face. Her pale lips are turned up ever so slightly, and someone has filled in her patchy eyebrows with a black pencil. The top half of her face is angry—like she’s ready to stab someone—and the bottom half is almost smug. This is not the Olga I knew. Olga was as meek and fragile as a baby bird.”

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

You know what one of my favorite things about living with children is?

Missing things.

The other day I was stirring a pot of mashed potatoes, and I laid down the spatula and went to dig in the freezer for some broccoli I could lay out on a cookie sheet and pour olive oil over and roast in the oven. And then I went to stir the potatoes again, because they were boiling great white foam over the sides of the stainless pot, and my wooden spoon was gone.

None of the boys were around. I hadn’t heard anyone come inside or go out. I searched high and low, thinking maybe it had fallen on the floor and I just couldn’t see it because I had some unexplainable spoon-shaped blind spot. There aren’t many places a bamboo spoon can hide. It wasn’t on the floor. I crawled on my hands and knees, just to be sure. So I gave up and took out the metal spoon, which was probably a better one to use anyway. Oh, well. Not a big deal. I probably hadn’t stirred them in the first place.

I drained the potatoes and unwrapped the butter to melt in them and shook out some salt and hooked up the mixer so I could make them nice and smooth, and then I called the boys in for dinner.

You’ll never guess what happened. One of those 3-year-old twins came traipsing in with the very bamboo spoon I remembered stirring the potatoes with, like I hadn’t been using it first. He must have sent a ninja to do his dirty work, because when he’s trying to steal books from the home library after lights out, his footfalls are so thunderous they resemble a herd of elephants fleeing whatever makes elephants run. I heard nothing this time around.

If it hadn’t been so maddening, I would have been a little bit impressed.

I can’t keep a house tidy, because boys keep swiping my stuff. They’re like practiced thieves when it comes to things like wire whisks and flashlight batteries and the last of the flour in the freezer. The other day, I found a metal nut cracker upstairs in their room, because they “wanted to see what happened when you use it on a bouncy ball” (sadly, the ball is no longer with us). I will find perfectly good table spoons out in the backyard, because they “wanted to see how long it would take to dig to the earth’s mantle using a silver spoon” (You never actually get there, because there’s too much limestone in our soil. And it would take twelve hundred years.). I will find random things in the freezer, because someone wanted to know “what would happen to a glass mixing bowl when you fill it with water and put an old banana in the middle of it and freeze it.”

Tell me, please, how it’s remotely possible to keep a clean and tidy house when you don’t even know where half your possessions are? The 8-year-old has broken into our bedroom while both of us were occupied by boys downstairs and stolen paperclips, because he wanted to clip all his papers together, and by the time we found him, he had a string of a hundred paperclips already wrapped around each other, because, in his words, when he looked at that paperclip in just the right way, he realized that he could string them all together and that would make a really cool decoration for his room, which he plans to put…

On the floor.

Boys use forks to try to dig out rocks, no matter how many times you tell them to keep what’s inside inside (and no matter how many times you almost curse because you just stuck a prong up your nose while the rest went in your mouth, where they’re supposed to go). They will use butter knives to carve boxes into houses and leave the knives on the table instead of putting them back away so the next time we need to spread butter or jam on something, there’s no utensil left that will work. They will use baby spoons to pretend that their stuffed animals are eating something tasty, and when you need to feed the real live baby in your house, those three metal spoons have disappeared into the black hole of a 5-year-old’s room.

And the most annoying part of it all is that you won’t even know those things are missing until you finally need them, which for some things is a relatively long time. I didn’t notice the foil was gone until I had a dish, months later, that didn’t have a lid, and I needed to use it to cover our leftovers. And when I asked the boys if they had seen the 500-foot roll of foil anywhere, the 8-year-old brought it back downstairs and said he’d been using it to “make a person out of a toilet paper roll.”

There are so many things that disappear in a house with children, and they will not turn up until you’re kneeling down on the floor and that missing object comes out to maul you in some way. You will not realize your serving spoon went missing until you sit on the couch and you suddenly have bamboo up your bunghole. And then you’ll wonder who in the world managed to lodge a spoon down the crack of the couch (and now in another crack) when they’re not even allowed to eat in this room, and you’ll never know, because they’re too busy laughing at how it’s perfectly wedged between your cheeks and you’re, honestly, too busy trying to get it out and, after that, trying to walk back to the sink, because it may be easy to recover from an injury like that one when you’re 8, but it’s much harder when you’re 30.

So, in a way, it’s actually pretty hazardous to live with children, because they’re always setting up traps for you. And I would be willing to bet they really like doing it, because it’s pretty funny to see a mom limping around after stubbing her toe on a metal bowl that was hiding under a blanket she kicked in her frustration because it shouldn’t have been on the floor, yet again. I guess it is pretty funny. I guess I can at least give them that.

But I cannot give them permission to use my household utensils for God knows what. I will have to draw my line there, because those are things I need. Seriously, kids. Stop trying to pretend your lunch containers are doggie bowls for your stuffed animals. If you want a lunch tomorrow at school, curb your creativity a little. I promise you’ll find plenty of other supplies elsewhere, if you’ll just get out of my kitchen.

This is an excerpt from The Life-Changing Madness of Tidying Up After Children, the second book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Jarosław Ceborski on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

It is difficult being a strong woman.

To have our opinions, which are not always the “right and proper” opinions, to assert these opinions, to be dismissed for them; to be passionate about the things we are passionate about; to step out into the wilderness that holds no shred of similarity to the popular way of things embraced by the tribe—it is not without its dangers.

There are days my insides have burned liquid from the passion of my purpose, and there are days my insides have frozen solid because I don’t know if I should say what needs to be said—I have watched too many strong women get knocked to their knees, and I don’t know if I have what it takes to get back on my feet when the same comes for me.

Strong women brave the consequences of their strength. There is never a shortage of critics and judgment and misunderstanding leveled at strong women, because women, historically, have been shoved into neat and pretty—convenient—boxes. Stay here, stay silent, stay small.

The problem is that I have never liked boxes, they way they press in on all sides and make it hard to breathe, the way they cut off the light with a darkness that feels inescapable, the way they smell of dust and fear and the death of what had lived. So though I know what a strong will and heart and mind can do to a woman’s reputation, I choose to step out of the box, tape it up, and toss it back at the ones who would like me to remain curled up inside it, silent and small.

I will not be silent. I will not be small.

(Photo by Ryan Moreno on Unsplash)