by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

Author

Every book I write

contains pieces of me, my

mark on the wide world.

Know, How to

If you want to know

who I am, all you have to

do is read my books.

Write

I am learning how

to bleed on a page for you

So be kind, reader

These are excerpts from Life: a definition of terms, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of volumes for free.

(Photo by rawpixel.com on Unsplash)

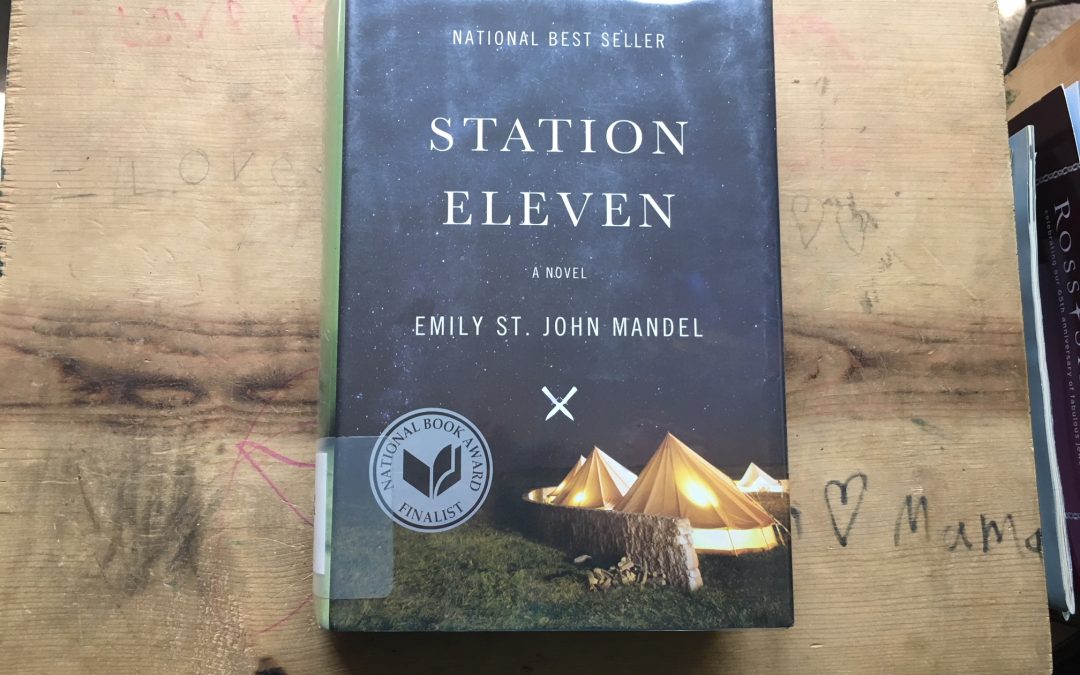

by Rachel Toalson | Books

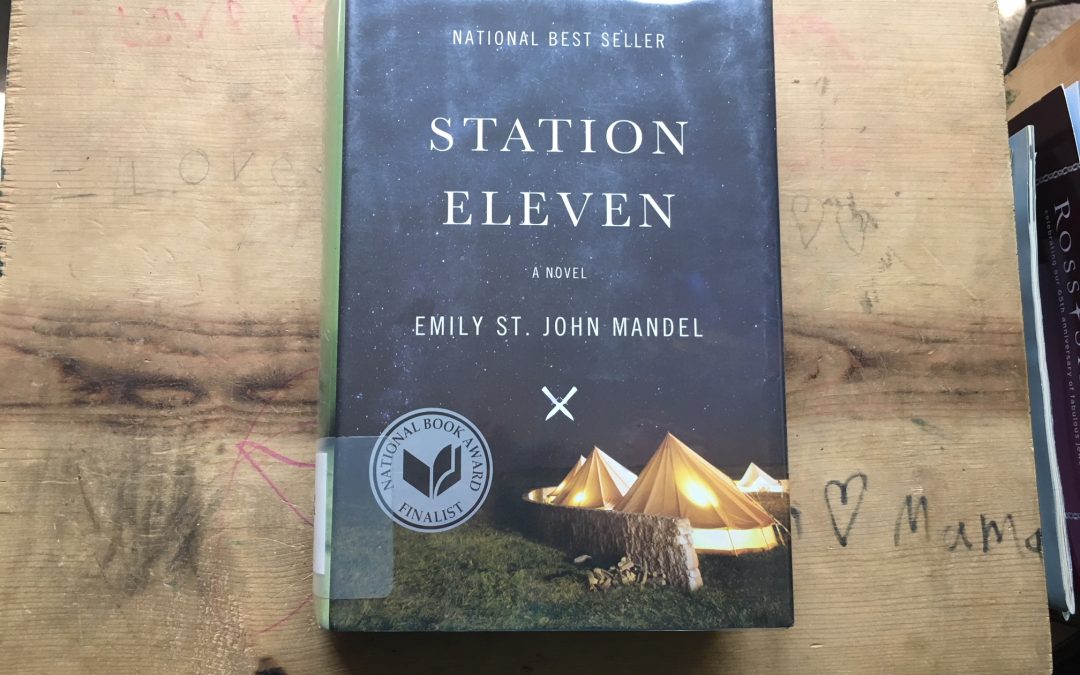

I don’t read a whole lot of adult novels, but I kept seeing Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel, pop up on my social media feeds, and I decided to give it a try. I’m glad I did.

This is an adult science fiction book that features a post-apocalyptic world, in which a virus called the Georgia flu wipes out everyone.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The premise: The Georgia flu wiped everyone from the earth, except for a select few, who learned to survive as our ancestors once survived. It was futuristic but had the feel of a step back in time, because there was no Internet or social media channels or even ways to communicate effectively with other people. The people were all spread out, so the earth wasn’t very populated, or didn’t seem so. It was an interesting premise from which to start a story. There was a traveling symphony that met up with some prophets who claimed there was a reason some people survived and others didn’t. It had a cult-like feel that was both intriguing and disturbing.

The structure: The storyline moved from the future, when the virus had already killed most of the world, to the past, where nothing yet had happened. I found this a very interesting method for the storytelling. While most of the people whose stories were told in the “before” section were no longer alive in the “after,” there were some who had carried on, luckily enough, and it was interesting to see where their travels took them.

The characters: Most of the characters were actors or artists, people who had performed on stage and a woman who was writing a comic book called Station Eleven. This comic book connected all the pieces of the story, even though it didn’t seem like an important part of the story. It was a great symbol that linked past to present.

I was hooked by the opening paragraph:

The king stood in a pool of blue light, unmoored. This was act 4 of King Lear, a winter night at the Elgin Theatre in Toronto. Earlier in the evening, three little girls had played a clapping game onstage as the audience entered, childhood versions of Lear’s daughters, and now they’d returned as hallucinations in the mad scene. The king stumbled and reached for them as they flitted here and there in the shadows. His name was Arthur Leander. He was fifty-one years old and there were flowers in his hair.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents, Wing Chair Musings featured

I don’t know if I’ve ever faced a harder challenge in my parenting years than raising twins.

Maybe it’s because our twins came near the end of the line of boys and they see all their older brothers do, and they expect that life will be exactly like that for them.

Except there are two of them.

Oh, you want to drink out of a big-boy cup because your older brother did it when he was 2? I’m sorry. There are two of you. You want to sit free at the table instead of strapped into your chairs because all your brothers did it when they were almost 3? I’m sorry. There are two of you. What? You want me to leave the baby gate on your door open because you haven’t yet figured out how to climb over it (it’s coming)? I’m sorry. In case you haven’t noticed, THERE ARE TWO OF YOU.

Our twins are identical, two sides of the same egg. Nature’s gift, doctors say. One is left-handed, one is right-handed. They complete each other.

That’s part of the problem. What one doesn’t think of, the other does. What one is afraid to do, the other will try. It’s like having four toddler wrecking balls walking around the house, scheming about what they can destroy next. I imagine their conversations go a little something like this:

Twin 1: Hey. Hey, brother. Mama’s not watching. Remember how she told us not to touch this computer? She’ll never know if we do. Where is she?

Twin 2: She’s in the bathroom. Remember what we did last time she was in the bathroom?

Twin 1: Oh, man. That was fun. But back to this computer. She’ll never know. I just can’t figure out how to open it.

Twin 2: Like this. But how do you turn it on?

Twin 1: Easy. I’ve seen Daddy press this button right here.

Twin 2: There it is.

[Mama comes back into the room with the baby she just changed.]

Twin 1: Close it, close it, close it!

Twin 2: Walk away. Not too fast, not too slow. Just enough to look like we weren’t doing anything. And make sure you wear the wide eyes. She thinks they’re cute.

I love my twins. Of course I do. It’s just that they were completely unexpected.

If I could have read a primer two years ago, this is what it might have said: Every parent of twins needs…

1. An extra dose of patience.

You will need this for many things. You will need it for the stranger at the store who asks to see your amazing bundles of joy and, after looking at their angelic sleeping faces, declares she “always wanted twins” and you want to say, “Oh, really? Then take mine,” because one was up screaming at 3 a.m. and as soon as you got him calmed down two hours later the other one woke up screaming, and as soon as you got that one calmed down an hour later all the other boys were up asking for breakfast. Which woke up the twins, who were also hungry. Again.

You will need this extra dose of patience for when they learn to talk and there are so.many.words and so.many.whys and so many demands for everything under the sun. You will need it for the potty training and the big-boy-bed transitions and the constant fighting from dawn until dusk.

You will need it for the times you were helping one out of his pajamas and into his day clothes and you return back downstairs to find all the jackets removed from your poetry books and spread across the living room floor like a special carpet for toddler feet, for the six thousandth time (You should probably just put those books away, Mama. Far, far away.).

2. Good decision-making skills.

These will come into play those times they both wake up at 3 a.m. because they’re hungry. Which one do you feed first? (Answer: You’ll figure out a way to feed both.)

You’ll need these skills when one twin is in the downstairs bathroom playing with a plunger in a potty you specifically remember your older boy didn’t flush five minutes ago when he stunk it up and the other is in his bathroom upstairs finger painting the mirror with a whole tube of eco-friendly toothpaste. Which do you get first? (Answer: The toilet one. Toothpaste is much easier to clean than the mess an overzealous plunger in a pile of poo can make.)

You’ll need them when the one who’s known for wandering does exactly that, moves from his nap time place while you take a minute or five for a shower, because it’s been four days since the last one, and you walk out to find him playing with the computer he’s been told 50 billion times to leave alone and, in his panic to close it, he deletes the 1,500 words you wrote this morning before kids got up. What do you do? (Answer: Cry.)

3. A rigorous workout regimen.

When one is running down the street because someone forgot to lock the deadbolt he can’t reach and another is going out back without shoes in 26-degree rain, you’ll want to be in tip-top shape for that. I recommend interval training. That way when they stop and change directions, you’ll be ready. You’ve done this a thousand times. Ski jumps. Football runs. All-out sprints.

When they slip, unnoticed (because they’re like ninjas), into the playroom while you’re wiping down the table after a ridiculously messy lunch, and both of them come out with their scooters, you’ll want to be able to wrestle those “cooters” from screaming, flailing bodies without hurting anyone.

And when one collapses in the middle of the park because it’s time to go and he’s not ready yet and the other thinks that just might work, you’ll need strong arms to carry thirty-two pounds of kicking and screaming twins back to the car, one tucked under each armpit.

4. Containment measures.

This would be things like strollers until they’re 3 and booster seats until they’re 4 and a baby gate on their door until they’re…15. Well, maybe 13.

It also means leashes at the city zoo on a packed day, even though you said you’d never use them and you can feel the disapproval of other people and you want to say, “Come talk to me when you have 2-year-old twins. These things have saved their lives 17 billion times, and that was before we even got out of the parking lot.”

Containment saves lives. And sanity.

Twins are great. And hard. And maddening. And great. And so hard.

They can disassemble an 8-year-old’s room of LEGO Star Wars ships in 3.1 seconds. They can disassemble a heart with one identical smile and a valiant try at saying “Uptown funk you up” that sounds like it should have come with a bleep.

There’s just nothing like them in the world. You’ll be so glad you get to be their mama.

Especially after they fall asleep.

This is an excerpt from Parenthood: Has Anyone Seen My Sanity?, the first book in the Crash Test Parents humor series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Helen Montoya Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

All day long I’ve been checking comments and shaking my head and feeling distracted by this war happening online, on my space, so I didn’t get much work done.

Many of the comments are kind, but too many of them are not. So I sit down to my computer and get ready to fire back my responses. Something about how we should take care with our words and assumptions and especially strangers’ hearts.

My husband puts his hand on my arm. “It’s not worth it,” he says. “You can’t argue with people like that. You just have to ignore them.”

I scan the tirade one more time, and every single one of them pouring poison online holds up a “freedom of speech” card, claiming their right to share their opinion. And yes, it’s true. We do have the right to our own opinion. But just because we have the right to free speech and the freedom of expression, does that mean we should use it to air everything we think?

This is a harder question to answer.

///

When I was eleven years old, I stood outside the little Baptist church I attended on Wednesday nights and watched a friend play basketball with some of his older buddies.

Another girl watched, too. She had a crush on my friend, but he didn’t ever pay any attention to her, mostly because he had a crush on me. I didn’t see him as anything more than a friend, so I kept trying to bring them together. But my efforts didn’t work.

And there came a day when the youth leader called us all inside and the boys went one way and the girls went another, and my friend hugged me and said he was leaving early and wouldn’t see me again until school the next morning.

The girl was watching. The boys disappeared, and she turned to me and said, “You have a really pointy nose.” Then she walked away.

Maybe it wouldn’t have affected me as much if my dad hadn’t just left my family for another one. Maybe I wouldn’t have been as bothered if I hadn’t already been uncomfortable in my skin. Maybe I could have let it go if I hadn’t already been walking my way toward eating disorders and wishing I were different.

I can’t say for sure, because that wasn’t my reality then.

I tried to pretend her words hadn’t hurt me as much as they did. I tried to keep my fingers from tracing the shape of my nose. I tried to walk past the girls’ bathroom without ducking inside.

But I did go inside, and I stood looking at my nose in the mirror for five whole minutes, turning to examine it from every angle.

Yeah, I thought. Yeah, I see what she means. It is pointy.

If she thought it was pointy, how many other people did, too?

///

Even today, in my dark days, when I find myself unhappy with my appearance, her voice joins the others in their raucous chorus.

What does it matter? you might say. What does it matter what one little girl thought? What does it matter what other people think? You shouldn’t be so weak to care. You shouldn’t be so insecure about yourself that the words of another person can hurt you.

The problem is that we are all, at the heart of us, wired for connectivity. What exercising our freedom of speech and our right to our own opinions through personal attacks on other people does is it disconnects us from the human experience of community. It casts outside the circle the ones being attacked.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. It was the first global expression of the basic human rights all people could claim. Freedom of speech was added as Article 19 in 1949. Article 19 said that “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

This idea of free speech and expression had been developing since the advent of the printing press. Traditionally, governments had limited printing opportunities to only those materials that the government agreed with. Because of this limitation, political ideas could not be freely debated.

Free speech and the free expression of ideas was originally a political, intellectual right, not a personal one meant to justify airing our opinion about everything.

Governments still restrict freedom of speech and expression based on the harm principle, which says that one’s freedom cannot be used to harm another. Some of those restrictions include libel, slander, hate speech, fighting words, and oppression. There are many others.

Article 19 also states that the freedom of speech and expression carries “special duties and responsibilities…for respect of the rights or reputation of others.”

This is the part we seem to have forgotten.

///

In college I worked as the editor-in-chief of the college newspaper. There were a few rotating cartoonists who would publish editorial cartoons with us.

One night a cartoonist turned in his cartoon, and I immediately had a bad feeling about it. In the cartoon, a professor stood at the front of the class. A bubble above him said, “Blah, blah, blah.” The students around him all had hostile expressions on their faces. Some were sleeping. A few were throwing things at him. One, I seem to remember, had a gun, though I’m not entirely sure my memory hasn’t fabricated this detail, perhaps made the cartoon worse than it really was because of what happened later.

I called the cartoonist to see if he had anything else he could send me.

“Why?” he said.

Because this one didn’t seem very respectful, I said.

“It’s not a real teacher,” he said. “It’s just a joke. It’s a humorous opinion.”

He said he had nothing else to give me, and I was two hours from deadline with nothing else to fill the space.

So I let it run.

The next afternoon, when I got to my office, my voice mailbox was full. My email was inundated. People were outraged by the cartoon. It shouldn’t have run.

It seemed that everyone but me knew who the professor was, because even though the name had been changed in the cartoon, the picture, they said, was a dead giveaway.

I had to not only submit a formal apology for letting something so insensitive print in the paper for which I was responsible, but I also had to fire a really good cartoonist who’d probably just been annoyed at a teacher for some reason or another and decided to lash out in the best way he knew how.

Just because we have freedom doesn’t mean we should use it.

///

With this freedom comes great responsibility.

We are responsible for our words and whether they build up or tear down. We are responsible for the hearts of one another.

In this day of computer communication, with our ever-increasing ability to comment anonymously all over the Internet, we have gotten really good at firing off responses, without really thinking about how, at the other end of our words, there is a real, breathing person.

We can’t see their face. We don’t know much about their lives. We assume the parts that are missing.

It’s easy to forget our responsibility.

I don’t have a problem with a friendly exchange of ideas, with a person who can respectfully disagree with what I have to say, someone who makes a good effort to convince me of his or her viewpoint without feeling the need to make it personal. But when someone starts attacking me or the members of my family, saying destructive, hurtful, dishonoring things they have no way of knowing for sure, that’s when they have lost their ability and their right to communicate with me.

What freedom of speech really means is expressing our opinions or viewpoints in a way that does not damage other people or people groups. It means carefully weighing our words and running them through a filter—is it kind? Is it true? Is it necessary?—and only speaking when our words pass the test. It means seeking harmony and peace even in disagreement.

We cannot claim our right if we do not exercise our responsibility.

Freedom of speech has the ability to broaden our minds in astounding ways, introducing us to new ideas and uncomfortable viewpoints and enriching humanity’s full experience of life.

We just have to know how to use it.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Gerson Repreza on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

they will tell you

who you should be

what you should do

how to be someone

they all like

someone the world

accepts

someone who

won’t cause

problems

inconvenience

challenge

they will tell you

how to be successful

and why their dream

is so much better

than your own

don’t listen

walk your own way

forge your own path

be kind

hold courage

keep dreaming

this is how

to be you

This is an excerpt from This is How You Know: a book of poetry. For more poetry, visit my starter library, where you can get some for free.

(Photo by Marion Michele on Unsplash)

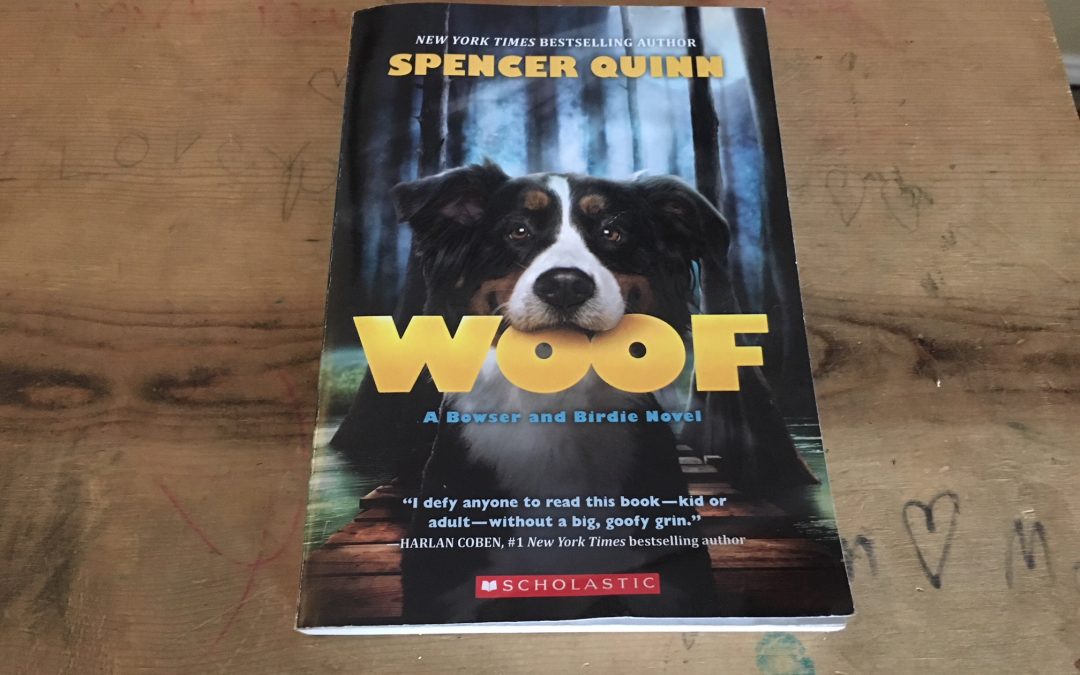

by Rachel Toalson | Books

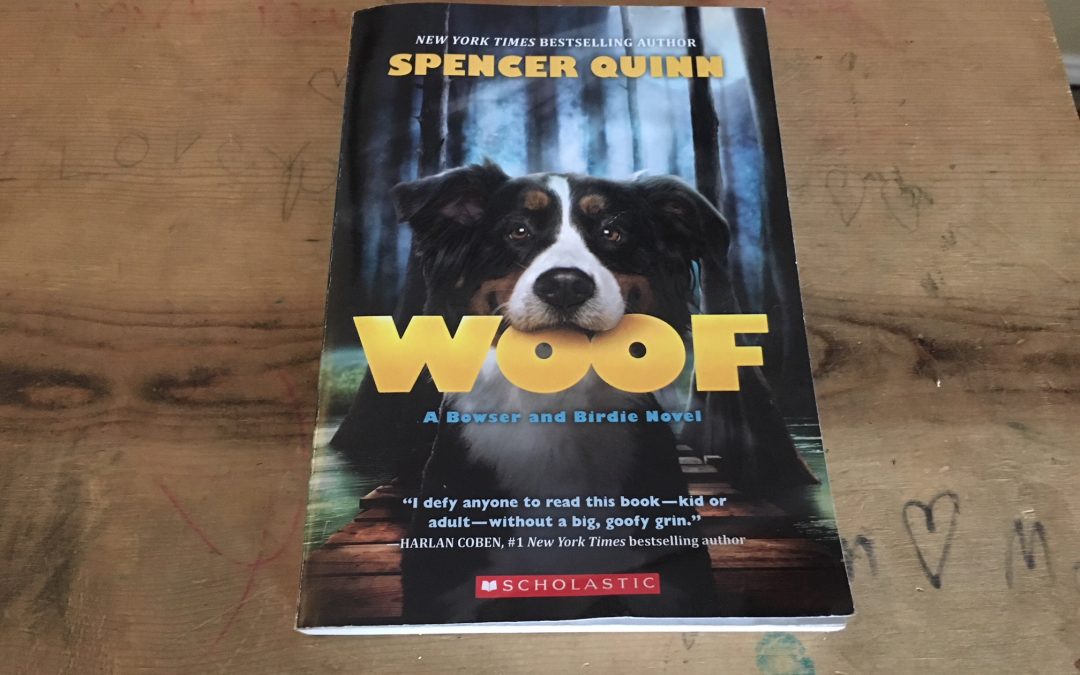

One of my sons loves stories with dogs. So after he read Woof, by Spencer Quinn, he left it on my bed, along with a note that said, “You have to read this, Mama.” And how could I refuse?

Woof was a sweet, engaging, sometimes humorous mystery, told from the perspective of a dog.

Yes. The perspective of a dog. It was delightful.

Here’s an example, taken from the first page of the book:

Two humans stood outside my cage, a white-haired woman and a gum-chewing kid. Gum chewing is one of the best sounds out there, and the smell’s not bad, either. I liked the kid from the get-go.

They gazed in at me. I gazed out at them. The white-haired woman had blue eyes, washed out and watery. The kid’s eyes were a bright, clear blue, like the sky on a cloudless day. I hadn’t seen the sky in way too long.

“How about this one, Grammy?” the kid said.

The white-haired woman—that would be Grammy, not too hard to make these human-type connections once you get the hang of it—pinched up her face, and it was kind of pinched up to begin with. “Eat us out of house and home.”

The kid cracked her gum. What a sound! I tell you what that does to me, shooting this buzzy feeling all the way from my ears to the tip of my tail and back again. “I don’t know, Grammy,” she said. “Looks thin to me.”

“My point exactly. He’s just waitin’ on some sucker to take him home and fatten him up. Check out the frame on him.”

What a great start!

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The sweetness. This was, at its heart, the story of a girl and her dog and the way they grew to love one another. While there was an intriguing mystery that threaded through it, the real delight of the book came from Birdie and Bowser’s relationship.

The point of view. I’ve already mentioned that the book was told from the perspective of a dog. This made it somewhat silly in some places but also incredibly sweet. Bowser would get lost in a train of thought or he would not know what the humans were talking about or he would try to figure something out as a real dog seems to be trying to figure out. He had a great personality, and Quinn did a fantastic job of portraying an authentic dog with authentic dog-thoughts.

The mystery. Throughout the whole story, Birdie was trying to figure out who stole her grandmother’s prize fish. There were twists and turns and plenty of personality.

After reading Woof, I had to talk to my second son about it. My third son overheard us.

“Did you find out who stole it?” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “But I’m not going to tell you.”

And I’ll say the same to you: you’ll just have to read it.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

My boys are fortunate to have two sets of grandparents who live in Texas. Their grandparents every now and then offer to keep them, in shifts, for the weekend, and they’ll take our boys all sorts of fun places and load them with sugar and feed them all the foods they’re not allowed to have in our house. They’ll let them stay up too late and deal with their whininess the next morning and effectively dismantle the schedule we sent them as a suggestion and then, two days later, hand them back to us with their eyes twitching.

“Here,” they’ll say. “You can have them back now.”

“You don’t want them for a couple more days?” we’ll say hopefully.

“Maybe next time,” they’ll say.

And we know there won’t be more days next time, because you know what? Raising six boys (even watching them for a couple of days) is really hard work.

On the way home from picking the kids up from the grandparents, the kids will typically tell us, in halting and never-ending fashion, about all the awesome food they had, which had sugar counts I don’t really want to know, and then they will, without even taking a breath, move on to all the fun things they did, like going to play golf and watching a movie every single night and swimming in a pool and swinging on a tire swing or digging in the huge dirt piles in their grandparents’ front yard and sleeping in their clothes instead of their pajamas and taking a bath all by themselves and having donuts for breakfast and going out to eat pizza and wearing their brother’s clothes instead of their own because grandparents don’t usually check labels and so don’t see that this crop-top belongs to the 3-year-old and not the 6-year-old.

Usually, while the boys are gone, Husband and I will work hard to clean up our house, which means that when we get home, the boys walk into a perfectly tidy, perfectly ordered house. Two minutes (or fewer) later, they will pull out all the stacks of artwork they did at their grandparents’ house and scatter the papers all over the floor because they think we surely want to see it all, even though it’s nothing new that we haven’t already seen. They’ll ask for dinner and go raid the fridge when we answer that it’ll be coming soon, and then they’ll have their first meltdown because there’s nothing good to eat in this house—at least nothing that compares to Lucky Charms and donuts and McDonalds and anything else that makes me sick just thinking about.

After this meltdown, they’ll progress into talking about how we’re the worst parents ever, because we never let them watch a movie or stay up too late or have donuts for breakfast, and we start going out of our minds trying to follow behind them and fix all the things they’re destroying as they’re walking around bemoaning the state of their life. We’d really like to start Monday with a clean house, but kids would really like to take that possibility and rip it into tiny little pieces we can’t see anymore.

We’ll move into the unpacking mode, splitting the shift where one of us unpacks and the other cooks dinner, but you’ll notice that both of these jobs leave few eyes to watch the melting down, tornado-like children. Dinner will be the worst dinner they’ve ever tasted, baths will be the worst time they’ve ever had in the bath, bed time will be the worst thing they’ve ever experienced in all their lives, and by the time the evening is finished, we will be the Worst Parents Ever.

There is definitely a detox time when it comes to handing off children to grandparents and then taking them back. We will have to detox their food expectations, their sleep expectations, their complete and utter lack of routine. We will probably be driven near out of our minds in the process. This adjustment period makes life feel like it will never be the same again. But eventually it will even out. And I will eventually be thankful that we took a weekend away and the boys got to have an opportunity to spend time with their grandparents for a couple of days.

On the surface, it might seem that the only reason a parent would want to send kids away with grandparents is to get a break themselves. And this is definitely one of the great perks of grandparent weekends. Husband and I have used our weekends to talk and actually finish a sentence. We’ve used them to cook dinners together that no one will complain about (although we usually have enough leftovers for an army, because we don’t know how to cook for two people anymore). We’ve used them to reconnect, dream, work, sightsee, and share a cup of coffee without a kid climbing on our laps (that’s not to say I don’t thoroughly enjoy my kids climbing onto my lap. I do. It hardly ever happens anymore, because no one ever wants to sit still anymore).

But what grandparent weekends also do is give two completely different generations an opportunity to get to know each other. Grandparents don’t have the burden of discipline like they did when they were raising their own children. They get to be fun. They get to be doting. They get to be the rule relaxers. This keeps them young—it’s been proven by science. Grandparents who take an active role in their grandchildren’s lives have sharper brains, more capable bodies, and greater heart health. (Keep that in mind, Mom.)

And kids get to experience their own benefits. It’s important that kids interact with another generation that is removed from their parents’ generation, because they can learn important things from their wisdom (like how you actually should wear deodorant when you turn ten). Kids get to experience the unconditional love of a grandparent who is not quite as concerned as their parents are over who they might turn out to be—because time has given grandparents perspective, and they know that everything irons out eventually. Kids get to be kids without someone continuously harping on them about picking up their dirty socks.

So while I start to dread the hand-off from a Grandparents Weekend about halfway into that freedom, I’m glad every single time that we sent the kids away perfectly calm and controlled and pick them back up crazy little wildings who forget what it means to brush their teeth and put away their clothes and do such things as after-dinner chores. I’m glad, because I know it’s all for everyone’s good.

My kids are currently climbing up the walls with their toe-knuckles. I’m currently scheduling the next Grandparents Weekend.

This is an excerpt from This Life With Boys, the third book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

A few months ago, my boys and I finished reading Roald Dahl’s Matilda. I had never read it before, so I was just as excited to reach that magical hour of stories as my children were, to see what Matilda would do next.

One of my boys’ favorite parts of the book was when Matilda slipped a newt into her principal’s drink—to get her back for being unkind to children all the time.

A newt is a semi-aquatic amphibian—it can live on land and in water. It adjusts to its surroundings and becomes what it needs to become in order to belong. The newt provided a stark contrast to Matilda, who did not blend in to her surroundings at all but was something of a rebel.

After we finished the book, I thought for a long time about this concept of becoming who we feel we need to become in order to fit in. I thought about the climate of the world and how there are lines everywhere, and if you’re not on one side or another, you’ll get torn apart—and also, if you’re on one side rather than another, you’ll get torn apart, too. We are unsafe everywhere, it seems.

Human nature begs to belong. It is wired into our brains and hearts. But it appears there is nowhere to belong in a place so polarized and disjointed.

My husband and I recently read Braving the Wilderness, by Brené Brown. One of the main themes of the book was the importance of belonging to ourselves.

Here’s what Brown says about it:

“Belonging to ourselves means being called to stand alone—to brave the wilderness of uncertainty, vulnerability, and criticism…

“Belonging so fully to yourself that you’re willing to stand alone is a wilderness—an untamed, unpredictable place of solitude and searching…

“True belonging is the spiritual practice of believing in and belonging to yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.”

Sometimes belonging to ourselves means we’ll have to go out into the wilderness where it feels like we’re all alone; everyone else has jumped on a bandwagon of some kind or another. Sometimes it means we’ll have to step into the role of rebel and speak our mind, knowing that what we have to say won’t be popular. Sometimes belonging to ourselves demands more than we can give.

I often step into this wilderness—not perfectly. I look more like a colt who has just been born, just found her legs, just wobbled to her feet and begun to run because the only alternative is falling. It is not without fear that I walk into the wilderness—but something compels me. I must be who I am, which means I must do what must be done, which means I must brave the judgment, the criticism, the sometimes ugly face of disgust and vehement disagreement.

I must.

Many of my fiction stories examine people on the margins. I write about homeless children, about kids who grow up poor, about bullies and the bullied, about the mentally ill and vulnerable. I write about them, because their stories, like all our stories, deserve to be told. It is not always popular or easy. But it is what I must do, to be my authentic self.

It is not without great fear that I step off the path of least resistance. But courage is not the absence of fear. It is living with fear, embracing that fear, carrying it with you as you put one foot in front of the other.

May you be brave, bold, and steadfast in your journey to belong to yourself.

(Photo by Irina Kostenich on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

4:15:49

The early morning

hours, when the house sleeps still—

these are life-giving.

4:16:00

At times, alone can

be a breath of fresh air—when

one is a parent.

4:17:02

The scratch of a pen

against paper is one of

my favorite sounds.

These are excerpts from The Book of Uncommon Hours, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a few volumes for free.

(Photo by Brooke Campbell on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

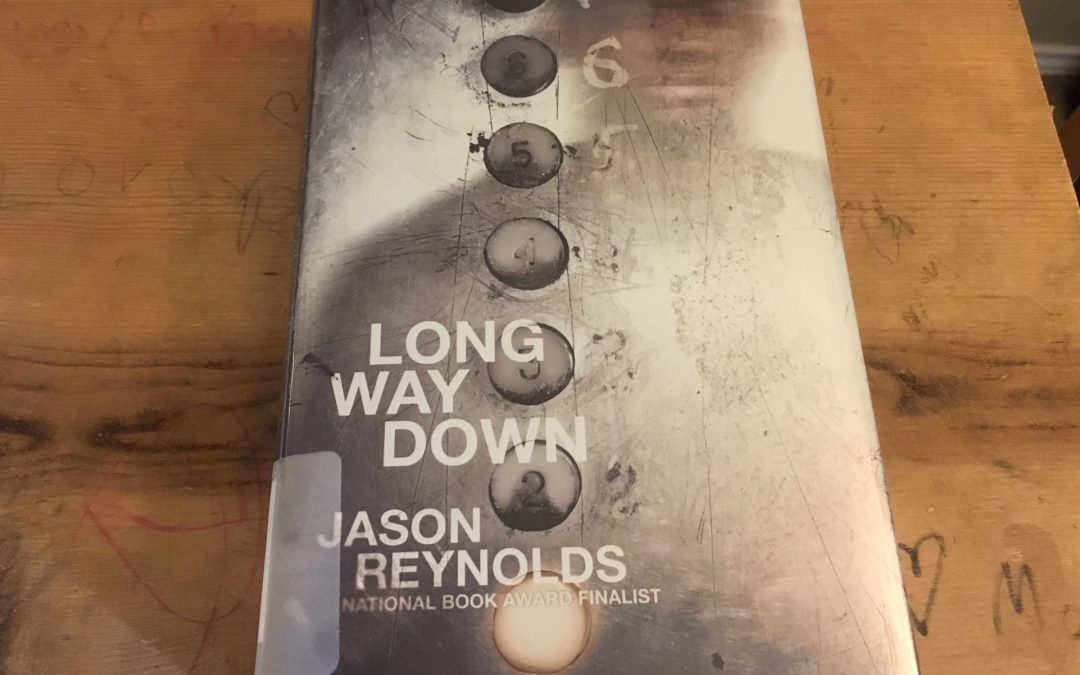

I’m probably what you could consider a super-fan of Jason Reynolds. I read practically everything he writes—his stories for young adults, his stories for kids, his well-compiled essays that print every so often.

The most recent Reynolds read I picked up was his 2018 Newbery Honor book Long Way Down.

This book is outstanding. Not only is it a fantastically told tale, written in poetry, but it is also an important one—one that examines revenge and gun violence.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

- The story. There’s not a whole lot that happens in this book; it takes place in the span of an elevator ride. But there is still so much that happens this story. A boy examines whether he will seek revenge for his brother’s gun death. He talks with people who have been killed before his brother. He agonizes over his decision. The story was unique and emotional and, at times, difficult.

- The window into gang life. Reynolds highlighted some of the street rules that exist in gang areas. He highlighted the cycles of revenge and violence. I read this book at the same time I was reading a research book on gangs to learn more about them, and I found that I understood them on a much deeper level after reading both books in tandem. There are never simple answers to anything, or simple reasons for why people do what they do. This book proved it.

- The poetry. I’m always a sucker for novels in verse, and this one absolutely did not disappoint. Will’s voice was engaging, connective, and intelligent, and Reynolds’s language was fluid and lyrical.

One of the things I’ve come to know about Reynolds, in reading so many of his books, is that he is a master at giving the voiceless a voice, and this is yet another book that achieves this laudable goal.

Here’s the first sentence, to get you started:

“Don’t nobody

believe nothing

these days…”

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.