by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

It never fails: by the time we get to Spring Break, my kids are done with school.

They’re done with homework, done with getting dressed, done with packing up in a timely manner. And, honestly, I’m so done with making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches they’ve become just jelly sandwiches.

The other morning, one of my school-aged sons came downstairs in his pajamas. I thought maybe he’d forgotten today was a school day.

“What are you doing?” I said.

“Going to school,” he said.

“You forgot to change,” I said.

“No?” he said, like he wasn’t quite sure. He looked down at his pajamas. “This is what I’m wearing.”

“You can’t wear pajamas to school,” I said. “Sorry.”

He groaned all the way up the stairs.

The school morning routine has become complicated.

I tell the 11-year-old to get up (multiple times), and he will still act like I’m the worst mom ever (for not getting him up) when I suddenly call out that it’s time to go (he didn’t hear me the twelve times I said it was time to get up). He hasn’t eaten breakfast, and he was supposed to take a shower this morning. I think it’s all an act. He’s allergic to showers; I think it’s been…well, you don’t want to know how long since the last shower I know about.

There’s so much chaos in the kitchen they have to yell to be heard. The other morning one of them was trying to tell me something, and it was so loud that I leaned close and said, “Say it in my ear. Maybe that will help.”

Not only did he say it, but he also sprayed it, and I got to both smell the delightful breath and wear the fragrant spit of a boy who hadn’t yet brushed his teeth this morning.

They can never find their shoes. The shoes are right in front of their eyes. They could trip over them and still not see them.

Maybe they’re just afternoon people, instead of morning people.

Several of them have forgotten what school mornings even look like (it’s usually the ones who have been doing this routine for several years); they immediately head into the LEGO room, rather than sitting down at the table or packing up their folders or attempting to tie their shoes.

Most mornings, one of them is running to catch up on the walk to school, and it’s not a silent catching up, it’s a whining—usually a scream-whining—one. My favorite.

On a typical morning, when I get back home, I see that someone forgot to close the back door and all our air conditioning has filtered out into the great wide world because that surely helps bring the Texas temperature down.

I didn’t know until I became a parent that March madness was actually a thing.

I’ve stopped signing folders, I get notes about overdue library books, I don’t even enforce homework anymore. Guess I’m ready for summer, too.

Wait. No. I take that back. I’m not ready for summer at all.

But it’s coming at me like a comet. Ready or not.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

If you ever want to know how much you don’t know, just spend about a minute with a kid.

Do you think there were rattlesnakes in the water?

No. Water moccasins, maybe.

Are they poisonous?

Yes.

Do they just bite you if you’re in the water, or do they have to have a reason?

I think if you disturb the nest they’ll bite you [this information comes from an episode of “Lonesome Dove” that I remember my mother watching when I was a child. I was slightly traumatized by it.]

Where do they nest—in the shallow water or the deep end?

I don’t know.

How many nest together?

I don’t know.

Do they have families?

I don’t know.

Can you describe them to me?

How long does it take them to have babies?

How many babies do they have?

Do they lay eggs?

Are the eggs waterproof?

Turns out, I don’t know very much at all.

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

Shopping

Everything takes twice

as long when you bring with you

a parcel of kids.

Not Listening

He talks nonstop of

Minecraft; I find attention

quite hard to give him.

Rule-breakers

They jump rope in the

house, which makes me want to trip

them up and then laugh.

These are excerpts from Life: a definition of terms, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of volumes for free.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

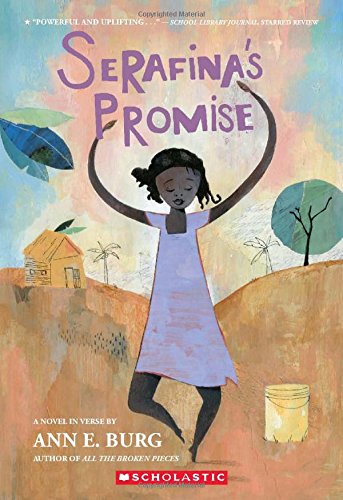

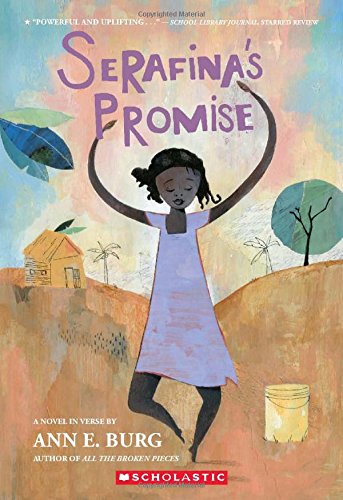

I’m always a sucker for novels in verse. Ann E. Burg is one of my favorite authors who writes in this style.

Her book Serafina’s Promise is a middle grade story about life in Haiti and a girl who dreams of a better future than her community can offer her. It was a lovely book.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The simplicity. Burg is a master at taking a complicated story (like life in Haiti) and distilling it down to the barest parts that will have the most impact on readers. This book was a beautiful representation of what modern life in Haiti is like. It examines what it’s like not to be able to go to school even if you wanted to. My sons take their access to education for granted here in the states, and it was a good reminder for them that not everyone has the same opportunities they have.

The emotion. There was so much longing in this story. So much courage. So much sweetness. Emotion was wrapped up in every line of this story.

The hope. This is something I love about middle grade literature: even when it deals with hard things—like floods and makeshift homes and earthquakes and the inability to go to school because of poverty—it ends on a hopeful note. This book was no different. The character of Serafina was a fantastically drawn representation of an 11-year-old with a dream.

Serafina’s Promise is one of those books to be read and re-read and re-read again.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

Tidying experts say that, among many other amazing things, you can gain confidence from the tidying up of your home. I agree. But I think we may be talking about two different things, because the confidence I believe can be gained from trying to tidy your house when children live in it is this:

You will fail at lesser things.

You will fail, one day, at beating your 8-year-old son at chess, because he’s in a club and you were never all that great at it, anyway, even though you tell yourself you used to be super smart. It was probably all a ruse.

You will fail at a cutting your boys’ hair the one time you try, because you were too cheap to pay the nominal fee you’d pay for a little boy’s haircut, and they’ll end up looking like a bowl sat on their heads while you chopped away.

You will fail at finding your keys when the kids have just used them to unlock the playroom, which is not really a playroom anymore but has become an obstacle course, a massive junk drawer, a “Hazard—Keep Out” kind of place. It didn’t used to be, but then you canceled your storage space, with the intention of cleaning out everything in it. Everything in it ended up in your garage, or playroom. But back to the keys. When your kids used them, they fell somewhere in this obstacle course of a room. Too bad you don’t have a location device on them. You’re probably never going to leave the house again.

You will fail at keeping up with school papers.

You will fail at remaining cool as your kid begins to care about cool. It doesn’t matter how many books you write or how many full-length albums you produce or how many beautiful art pieces you paint in the clip of a year. You are totally uncool, Mom and Dad.

You will fail at finishing those cloth napkins you planned to make for them when they all went off to kindergarten. And, at the same time, you will fail at finishing the crocheted blanket you were supposed to make for his sixth birthday and the other one you were supposed to make for the baby on his first birthday, because there’s just no time left. All your time is spent hanging out with the kids. That’s what you’ll tell yourself. It’s really spent signing school folders.

You will fail at kicking a ball past the little boy who now runs faster than you do, mostly because you have two 3-year-old cling-ons hanging to your leg, because this is how they said it would be a fair game of kickball.

You will fail at trying to learn how to roller blade when you turn 30.

You will fail at finishing that book in the time you thought you’d finish it, because boys make it nearly impossible to read.

You will fail at making your bed every morning.

You will fail at cooking a breakfast of fried eggs and pancakes, because there’s just not enough time, and, besides, they don’t want to wait that long.

You will fail at remembering whether the dishwasher was already run.

You will fail at hanging up laundry the day you wash it.

You will fail at shelving books every night, because by the time all the kids are down in bed, you have just enough energy to crawl to your bed and lie down.

You will fail at keeping your bedroom door closed any night, because at least one of the children will come knocking with something of emergency proportions, even if it’s just to tell you what their fart smelled like. Or that they love you. Both equally important.

You will fail at keeping even one puzzle with all the puzzle pieces.

You will fail at making sure the game of Operation doesn’t have any pieces missing.

You will fail at finding a full and complete deck of cards anywhere in your house.

You will fail at keeping toothpaste off the counters of their bathroom.

You will fail at keeping a toilet to yourself, because there’s always a time when they’re talking to you and they have to go right this minute, even though their toilet is only fifteen steps away.

You will fail at recycling those boxes before your kids see them and decide they want to make new toys out of them, and most of the time you’ll be glad that they’re so creative.

You will fail at keeping your plants alive and healthy.

You will fail at remembering to water your plants (sorry plants).

You will fail at cooking a perfect grilled cheese sandwich, because when your back was turned, your ears picked up on some suspicious splashing in the bathroom, and you know that sound, you know it well, so you investigated, and, sure enough, it was your 3-year-old, trying to plunge the toilet, even though he’s been told a billion times to keep his hands off.

You will fail at remembering that things you said you could never forget. (What was it again? You have no idea.)

You will fail at trying not to make the sex talk with your kids awkward. It will always be awkward. Embrace awkward.

You will fail at keeping up with the lawn outside, because boys are constantly digging holes, and who has the time to cut grass when you’re just trying to reduce the mayhem that crops up in your house?

You will fail at trying to stay the same. Because when you’re a parent, your kids are constantly, day by day, hour by hour, shaping who you become—and who you become is better.

So, really, what failing at keeping a tidy house really affords you is the confidence that you will fail at many, many other things, and that you will be better, greater, stronger for your failing.

Bring it on.

This is an excerpt from The Life-Changing Madness of Tidying Up After Children, the second book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Tonight, over dinner, I had to talk to my boys about cancer.

It’s been pressing on my mind all day—the text from my sister-in-law. A week ago my brother, who never goes to doctors, went to a doctor. He woke up with a black veil over his left eye. He was nauseated to the point of disability. When he tried to walk, the world tilted, spun, and lost its sense of order.

They found a tumor.

It’s cancer.

Brain cancer.

In less than a week he’ll have brain surgery and begin chemotherapy. Everything is uncertain.

He could die, my 8-year-old said. Yes. He could.

He’ll be sick, won’t he, my 7-year-old said. Yes. He will.

Will it damage his brain? my 10-year-old asked. Maybe. We hope not.

What if they don’t get it all?

Will it spread?

Will it happen to me?

So many of their questions I could not answer. It’s cancer. It’s unpredictable. It has no pattern, no measurable origin, no certain outcome.

Our dinner ended very quietly, like a reverent prayer. And fifteen minutes later, when they had all done their after-dinner chores without a single complaint, they were blissfully screeching on the trampoline out back.

I closed my eyes and listened to how predictably life goes on.

(Photo by Mario Calvo on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

I am an artist

I create

for the world

for you

for free

please

value what I do

see what it’s worth

dip your hand

in my well

and then appreciate

the beauty

instead of

taking, taking, taking

expecting what

isn’t really yours

an artist gives

but that

does not mean

you deserve

what they give

so let them know

what their words

their pictures

their songs

have meant to you

and give them back

your open hands

this is how

you love an artist

This is an excerpt from This is How You Know: a book of poetry. For more poetry, visit my starter library, where you can get some for free.

(Photo by Tim Marshall on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

I kept seeing Holly Goldberg Sloan’s Short on the library shelf, and I finally decided to pick it up and read it. I’m so glad I did.

The book is about a girl who just lost her dog, whom she loved, and, to cheer her up for the summer, her mom signs her up for a local community production of The Wizard of Oz. It’s a story about a girl coming to terms with loss, growing up, and the expectations we hold for our lives.

Here are three of my favorite things about Short:

The personality. Julia, the main character, was such a strong, wonderful personality, and that came through clearly in the book. It was sweet and refreshing to hear a girl with such opinions and interests.

The sweet story. This was a true coming-of-age tale that children will identify with and learn from, as can be seen by the last lines of the book:

“I grew this summer.

Not on the outside, but on the inside.

And that’s the only place where growing really matters.”

The engaging nature of the voice. Julia, because of her quirky voice, was a very engaging character, and the opinions she would voice were so much like what I imagine is going through the mind of a child or adolescent (sort of random but also connected in a strange way). Sloan has a knack for highlighting an adolescent’s associative thinking, and it’s a brilliant way to engage young readers.

All in all, Short was an incredibly sweet story that I’ll be recommending to my boys with gushing praise.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

A few weeks ago I got a text from my sister, who had her third baby in February. The text said, “Tell me you have days when you just can’t handle it. When walking out of the house is all you can do to survive. I just need to hear it from another human.”

I laughed out loud, even though I knew she was dead serious. And in my head were responses like “every single day” and “just this morning” and “on a minute-by-minute basis.”

Parenting is hard. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I used to run six miles every morning in Houston’s 10,000-pound humidity before commuting an hour to downtown’s Houston Chronicle office. I used to marathon-train on ten miles of hills pushing a double baby stroller that carried a 4-year-old and a 3-year-old. I used to work for a narcissist.

Parenting is still the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

There are so many hours of my day that I just feel like giving up and hitch-hiking to downtown San Antonio’s Riverwalk, where Husband and I had a life before children—a life that didn’t include a panic attack every time a kid steps too close to the edge of the path and I imagine having to jump into that river’s dirty black water to save him.

Like the morning last week, when the 3-year-old twins went outside into our very safe (normally) backyard while I transferred a load of laundry from the washing machine to the dryer. Two minutes, tops. That’s all it took. By the time I finished, one of the twins had come back inside, and the whole house smelled like gasoline.

“Why does the house smell like gasoline?” I said, to no one in particular. The twin looked at me. I looked at him. He had his guilty eyes on.

“What were you doing out there?” I said.

“Nuffing,” he said.

I knew it was definitely something, because of those guilty eyes. A mom always knows, after all.

His twin brother came in smelling like a gas pump, so I looked out on the deck, where they didn’t even have the foresight to hide what they’d been doing. There, on a deck chair, was a gas can their daddy uses to fill up the lawn mower the three times a year he mows. That gas can is stored behind a locked door. A locked and sealed door that somehow, SOMEHOW, these Dennis the Menaces had cracked open in less than two minutes.

They poured gasoline (less than half a gallon, for those who are concerned) all over the back deck, the grass, and themselves. It’s a good thing no one in my house smokes, because we all would have been blown to high heaven.

I put them both in the bath (which was not on the schedule for the morning) while the baby stayed downstairs in his jumper seat wailing because he doesn’t like to be alone, and washed them, rinsed them, scrubbed them, rinsed them and washed them again. Husband sprayed off the deck (which also wasn’t on the schedule for the morning) and saturated all the grass, because a Texas summer hits 4,000 degrees, and we were afraid the sun might make the gasoline-drenched grass spontaneously combust and blow us all to high heaven anyway.

That morning was one of those give-up days, because there’s no way to be one step ahead in my house. There’s no way I can fully toddler-proof every room. There’s no way I can keep them out of every single thing they find to amuse themselves. It would take twenty-three of me, and as far as I know, cloning is considered unethical.

That morning I wanted to walk out and let them fend for themselves in gasoline-scented clothes that spread their stench all over the house in less than two seconds.

I used to feel guilty when feelings like this crept up. I used to beat myself up for sometimes wishing that they just weren’t twins, that there weren’t two of them ALL THE DANG TIME, that they weren’t so insatiably curious and 3 years old and nearly impossible to parent right now.

But there is something important I’ve learned in my years of parenting: Just because there are moments when we want to run away, when we want to flat-out give up, when we want to trade our challenging kids for easier kids for just this little moment in time so we can catch up and learn to appreciate them again, it doesn’t mean that we don’t still love them with a love that is never-ending.

These little, irrational humans can be the best and worst people we know on any given day at any given moment.

There are days when I want to sit down and color next to my 3-year-olds, because they’ve been playing so well together and the morning’s disasters have been minimal, and, gosh, I just love them so much, and then there are mornings when I want to put them on Craig’s list’s free page (I’d have to lie to really sell the idea, though. Something like “Two well behaved twins, of undetermined age.” Because what kind of crazy person would want two 3-year-olds voluntarily?)

There are hours when I love to comb through those old picture albums that show these two hooked up to machines because they were premature and remember how I fretted and cried and tried my best to help them learn how to eat, and there are days when those first moments feel like entire lifetimes away from this moment, when they stuck their whole arm in the just-used toilet to see what poop floating in pee feels like (They already know. We’ve done this drill before.).

There are minutes when I pull them into my lap and kiss all over their faces until they’re giggling uncontrollably, because they’re getting so big and so fun, and then there are minutes when I’m half-heartedly holding their big brother away from them so he doesn’t clobber them for marking all over his journal with a giant red permanent marker they found lying around somewhere (who keeps giving us permanent markers? Please stop.).

Parenting is not for the weak. This is the hardest responsibility we will ever have in our lives. Raising another human being to be a decent person is not easy, and there are many times along our journeys when we will feel like giving up and giving in and giving out.

It just comes with the territory.

So I fire off my response to my sweet sister. “Yes,” I say. “Just about every day. Doesn’t mean you’re a bad mother.”

Because it doesn’t.

These moments when we feel the tension between wanting to give up and knowing we can’t make us stronger parents. They make us better people. They drag us into a deeper understanding of love.

Good thing, too. Because my toddler just figured out how to open a can of paint Husband left unguarded and now the pantry wall has a Thermal Spring scribble-masterpiece drying on it.

I’m going to be one amazing person by the time this is all over.

This is an excerpt from Parenthood: Has Anyone Seen My Sanity?, the first book in the Crash Test Parents humor series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I walk into his bedroom, checking on him for the seventh time, interrupting my writing to do it, which means I’m already annoyed. Put out. A touch angry.

Maybe I waited too long to come in here, but there he is, sitting in the middle of a pile of clothes and their hangers. I feel the rage in my shoulders; haven’t I told him a thousand times to stay out of closets and drawers and his brothers’ beds?

My heart sinks to my toes, and I shake my head. His eyes stare wide, because he knows, he knows he’s in trouble for this, and then I see the worst of it: a wet spot on the pillow that no longer has a case because he stripped it off before he did his deed.

Did you pee on your pillow? I say.

Yeah, he says, and he doesn’t even look the least bit remorseful, just grins up at me like this is something to be proud of, this peeing on a pillow he’ll sleep on soon. It’s all I can do to pick him up and take him to the potty instead of throwing all those books across the room in a rage, because it’s every single day, every single day that I’m battling twins. It’s relentless and exhausting and, sometimes, way too much.

The tears run hot and wild on the way back from the potty. I put him in his playpen without a word and close the door, because I don’t even want to know what happens next. All the way back to my room I can feel the dam breaking, the one that’s been piling for too long, the one that ends in I don’t want to be the mother of twins anymore.

I never asked for twins, and yet, there they are, in the next room, tearing everything apart.

Especially me.

///

It was three months after losing a baby that we got pregnant again.

The baby-losing had left a hole so wide and deep it felt like it could only be filled with a new baby. So when I took that pregnancy test and it said yes, my heart healed the tiniest little bit.

We waited weeks to even go to the doctor, because the last baby had died at nine weeks and we didn’t know it until the twelfth week, and I wanted to make sure this one lived before I got my hopes up. Except my hopes flew high the minute I saw a positive test. Tentative and yet solid.

My husband came with me for the first appointment, because I could barely lift my head I was so sick—but mostly because the last appointment, when the screen showed a baby had died, I sat on an examination table alone, and he did not want me to do it again, if this one was not alive. My doctor’s nurse practitioner brought that familiar, bulky machine into the bright-white room, and it only took a second to see the two where there had ever been only one. We were shocked and excited and terrified, all sorts of emotions fighting their way to the middle of our hearts.

We had no idea what we were in for.

///

No one does, really, when they’re having a baby. Babies are unpredictable beings. But this was different, because there were two. We really had no idea.

No one told us how hard it would be. No one told us there would be days we wished we could give one away, and we knew which one it would be. No one told us there would be whole months where we questioned our ability to keep on keeping on, where someone’s You’re such great parents. I don’t know how you do it, would make us burst into tears, because we knew we weren’t “doing it.” No one told us we’d live with those daily thoughts that sounded a lot like They’re so cute, I’m so lucky I get to have twins, What’s cooler than this? and also like I give up and someone please take one of them and I wish I hadn’t had them.

We kept telling ourselves it would get easier. We believed it, too. After that foggy first year we hardly remember anymore, we told ourselves it would be easier because they would be older and could feed themselves. Except then they were mobile and there were two babies to keep safe and out of things and entertained so they didn’t tear the whole house down around us.

There were two drinks to pour and two drinks to keep on trays so they weren’t knocked to the floor where they’d make two big puddles of milk we’d have to clean up. There were four hands throwing food on the floor. There were two babies to change and two babies breaking into bathrooms to unravel whole rolls of expensive eco-friendly toilet paper into a now-stopped-up toilet and two babies turning on water faucets so they run for an hour before we even noticed. There were two babies tearing out the pages of books and two babies climbing out of cribs and two babies taking off diapers to play with poop. There were two babies getting into closets and drawers and pulling the stuffing out of stuffed animals and making holes in walls bigger and locking themselves in bathrooms.

Now there’s potty training and twice the accidents and twice the frustration and twice the I-just-peed-on-the-floor-because-I-felt-like-it-even-though-I-know-betters, and some days I honestly don’t want to do it anymore.

It doesn’t get easier the older they get. I know this now. There will always be two of them going through the same developmental stage, and, my God, I did not ask for this.

///

That first night home from the hospital, where they’d spent twenty days in neonatal intensive care for being born six weeks early, we tried assigning a twin to each of us, my husband and me. But then they both woke up at the same time for a feeding, and neither of us got sleep enough to take care of the three other boys who needed us, too.

The next night we parceled out shifts, with one parent taking the 11:30 p.m. and midnight feedings and the other taking the 2:30 and 3 a.m. feedings, and the first parent taking the 5:30 and 6 a.m. feedings. Except we’d start feeding one, and the other would wake up and scream to be fed. They were slow eaters, and the first one would take forty-five minutes to finish three ounces, and the second one would scream for forty-five minutes until he got his food, and neither of us slept, again. Every time I listened to those babies crying, my heart started crying, too, because it was already too too much.

We had tried to avoid it, because I wanted to hold my babies, but we finally, for the sake of sanity, caved to feeding them both at the same time in a swing and spent the rest of that year sticking bottles into mouths and counting down to when feeding time would be over, because we were overwhelmed and exhausted.

And then hard never left.

It didn’t take us long to know and understand that nothing about twins would ever, ever be easy.

///

Almost every time we take our twins out in public, at least one person will ask if they’re twins, even though they look exactly alike. Yes, we’ll say, they’re twins, and it never fails what they’ll say next:

So cute, they say. I always wanted twins.

My husband and I will look at each other.

No. You didn’t, our eyes say to each other. You want the idea of twins, but you don’t want twins. Trust us. But we smile politely and say, yeah, twins are really fun, because they are really fun sometimes, and then other times they’re maddening and crazy and way too much to manage.

A whole lot of the time they are crazy-makers.

Twins are the hardest challenge I have ever faced in parenting, and I would never wish them upon anyone. It sounds terrible all packaged like that, but it’s true.

People also like to tell me all the time that they had kids who were really close together—almost like twins. I have done that, too, with Boy 2 only fourteen months older than Boy 3, but it is not the same as twins. Not the same at all.

My twins beat me and break me and bust me all up inside, and sometimes I don’t even know how to handle all the hard they bring to a life. Sometimes I don’t even want to.

///

Last spring my brother and sister-in-law announced that they were pregnant with twins. I felt excited for them, of course, because they’d waited so long to have a baby, just one. But I also felt afraid, because I know how tough twins are, how tempers can fly and anger can follow one in and out of rooms for days on end, without explanation.

I knew that there are days when you feel strung so tight you know you can’t take one more thing because of the ringer your twins wrapped you around this morning, and then you’ll open a door to walls and a floor and two babies, who were supposed to be sleeping all this time, covered in poop. And there are days when you think it might be getting easier, and then a twin climbs over the gate barring the upstairs and pulls half the books in the library down before you can get to him, and you’re so busy picking up all those books you forget there’s another unsupervised one downstairs, and before you can make it back down, he’s pulled out the entire economy package of four hundred Band Aids and stuck them all to the bathroom floor. And there are days when one will run out the back door without shoes and you’re trying to chase him to get those shoes on and the other one will see his chance and run out the front door someone forgot to barricade-lock, and he’s halfway down the street before you even notice he’s gone.

There are days when, for a split second, you wonder if you should just let him go.

I couldn’t very well tell them all this, though, so I voiced my congratulations and then encouraged them to find help. I took pictures of poop walls and emptied-onto-the-floor closets so we could laugh about all those twinanigans that happen every other minute of a day and race a parent toward breakdown.

The day before Father’s Day, my sister-in-law went into labor twenty weeks early, and doctors couldn’t stop it, and she delivered them, two boys, and held them and watched them claw for breath they could not find because they had only the tiniest beginnings of lungs. And then she watched them die.

That night, I hugged my two babies a little tighter.

///

I know what a blessing every child is. I do.

I know what it’s like to lose a baby. I have.

I know how it feels to watch a child fall so sick he might die. He almost did.

I know what it’s like. I know.

I know the incredible gift of five healthy boys, the gift of another on the way, the gift of a home filled with wild, untamable boys. And I remember it all when they’re finally asleep and I can breathe again.

It’s just that during those waking moments, when a twin is pulling everything in sight off a counter because I haven’t had time to put away what his brothers stacked there, and another twin has found the pencil his older brother used for homework and is now marking all over the pages of a library book, I forget. There is not enough of me, and I forget.

I forget that one twin’s name means “swift and honorable,” how one day he will be strong and solid and mighty, how he is all of that now, bundled in a sometimes-unmanageable 2-year-old boy. I forget that the other twin’s name means “God remembers,” because he was a gift in the losing, two blessings that took away the one curse, how he shows love’s nature in his very being. He is all of this now, bundled in a sometimes-difficult 2-year-old boy. And even though mothering twins may be the hardest parenting challenge I’ve ever been given to date, I know, too, that they are tearing me apart every single minute of every single day.

They are the ones who pull those words from my lips: I just can’t do this life anymore.

This is a good place to be, I think—because it’s only when we can’t do this life anymore that we give an inch more to Another who can do it much better for us. I can’t do it is another door into surrender.

I can choose to raise these twins all on my own power and patience, and I will fail every time. Or I can choose to raise them on the power and patience of Another. I can drink from the well that will never run dry, and I will see victory every time.

I know what happens when I choose my own, limited power and patience. I think about how nice it would be to give one away, or I wish I hadn’t had them, or I see in a clouded way that covers all the sunshine they’ve brought into a mama life. Double laughter. Double joy. Double love, not just double trouble.

Clear eyes can see it better than clouded ones. So this day, I choose to see.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)