by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

“I’ve looked and looked and looked. Where could it be?”

It’s been three mornings of the same thing—he climbs out of bed late and almost misses breakfast, because there are LEGO pieces all over the floor and he can’t walk past them without building a miniature version of San Antonio’s Alamo. He’ll turn on an audio book, stretch out on the floor, and listen and build.

The problem is that there’s a deadline on mornings. This isn’t the case when school’s out, but it’s only the one-hundredth day of school, and so we still have another two hundred or so to go—which would make one think, if one were as gullible as I am—that maybe we would have gotten the hang of this by now.

Nope.

So there he is, playing with LEGO figures when there’s still a backpack to be packed, a lunch to be put together, shoes to be located. And the best part about it is he’s not very good at looking.

Yesterday morning he couldn’t find his shoes that were sitting under his desk, where he slipped them off while he was writing a thesis the other day (not really a thesis. But this particular boy will be well practiced at writing theses by the time he gets to college). He says one of his brothers probably shoved them under his desk as a joke, because he specifically remembers putting them where shoes go (“Where do shoes go?” I said. He just looked at me blankly, so, yeah, I think he’s telling the truth.).

Yesterday afternoon he couldn’t find the digital camera he got for Christmas to use in his filmmaking endeavors, and he ranted all over the house about how someone had taken it or stolen it or misplaced it (but that person was most definitely not him), and then when we found it on the table beside the couch, he, of course, had not put it there.

Last night he couldn’t find the soap container that was sitting on the edge of the bath tub, where it always is.

Today he can’t find his jacket. It’s right in the middle of the floor.

Once a week he can’t find a library book that someone—one of his brothers, probably—surely must have hidden on purpose. He can’t find this one specific LEGO piece, because they’ve all exploded on the floor and one looks so like another, but, actually, someone probably lost it (not him). He can’t find the CD player that’s still spinning because no one ever wants to press stop, only pause (“Can’t you hear the clicking, son?” “What clicking?”), which is hidden beneath the clothes he stripped off yesterday and left on the floor, because that’s where they belong. He can’t find his favorite Star Wars shirt because putting his clothes away after laundry day means stuffing them all into his drawers, instead of hanging them in his closet (one of these days, when he actually cares about the way he looks, he’ll realize that the “homeless” look isn’t all that compelling in the eyes of a young lady).

And it’s not just him. The rest of them got this not-great-at-looking gene, too.

“Where’s my scarf?” the 4-year-old says.

“It’s hanging around your neck,” I say.

“Where’s my backpack?” the 5-year-old says.

“It’s on the chair right behind you, where you laid it,” I say.

“Where’s Daddy?” one of the 2-year-olds says.

“You’re looking right at him,” I say. “How is it that you can’t see him?”

Kids just aren’t all that great at looking.

Husband would say they get this from me. “Have you seen my water?” I’ll say, and he’ll point to the banister in front of me, the most unlikely of places, which suddenly reminds me that I put it there a few minutes ago.

“Do you have the other keys?” he’ll say when we’re walking out the door. I’ll check my purse. “No,” I’ll say. He’ll look at me. And then he’ll pull my purse away from me, because clearly I’m incompetent at looking, and I’ll roll my eyes and mutter under my breath, “You’re not going to find anything. I’d be able to hear them,” and then out he’ll pull them. I have no idea how they got there.

“I can’t find his red folder,” I’ll say about the one boy missing a school folder.

“Did you look?” Husband will say, his voice muffled against the pillow because it’s still 6 a.m. and he likes getting up early.

“Yes,” I’ll say. “And he needs it today. There are important papers that need to go back to school.”

Husband will rouse himself from the bed and rifle through the billions of papers on our counter and miraculously find it at the bottom of the stack, where I swear it must have reappeared in the time between walking upstairs and now.

My Pride and Prejudice bag? I’ll say.

Probably in the closet, where it should be, Husband will say.

The sour cream? I’ll say.

Right in front of your face, he’ll say, grabbing it from the shelf that’s not actually right in front of my face but is more level with my forehead and above my line of sight.

My running shoes?

Downstairs in the basket, where they’re supposed to be.

Every now and then Husband will lose his wallet, and I’ll do a quick glance around the room, not see it anywhere, and already be on the phone with the credit card companies to cancel the two we carry, and he’ll walk back in the room with the wallet he found on the windowsill behind our blinds, where I wouldn’t even think to look (and why would I? What’s it doing there?).

I’m not entirely sure where this aversion to looking comes from. I blame it on the kids. I think I’m so overwhelmed with looking for things all the time that I just suffer from a condition called Looking Burnout, so when there’s something right in front of my face I don’t actually see it. One of the many hazards of having kids.

But something needs to be done about these kids and their sadly lagging looking skills. I’m not a find-this-for-me service. I’m not even a find-this-for-myself service, as you can see from the stories I’ve shared. So, eventually, someone is going to have to teach my kids how to properly look for something, and it’s most likely not going to be me. Which means it will probably fall to Husband.

Hey, you know what? We all have our own strengths. That’s part of what makes community important.

Now where did I put my computer?

This is an excerpt from This Life With Boys, the third book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Teddy Kelley on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I heard it first in a call from the school psychologist, summoned to get to the bottom of an eight-year-old’s acting-out behavior in the classroom two months ago (he was only seven years old when this journey began). But I heard it again in a face-to-face debrief meeting with his current teacher and the school principal and the psychologist, and it’s the weight of those ugly words, “I’m not as happy as I used to be” and “Nobody ever listens to me” and “I never seem to do the right thing,” collected during an interview between my son and the psychologist, that burn my eyes and the back of my nose.

I try to blink the tears away before all those other calm-and-composed women notice, but I can’t do it, because it’s my boy, eight years old, and this was not supposed to happen.

Depression was not supposed to happen.

One of the women runs off to get tissues, and I wonder if it’s bad enough to make my eco-friendly makeup run, because it’s easier to worry about the way a face looks than about the way depression looks.

These hormones, I say, with a little laugh.

And even though I’m eight months pregnant, it’s not the hormones, not really. It’s a little boy’s words. No mama expects depression in the boy she has loved and adored and cared for and watched and played games with and read to and hugged and kissed, every chance she gets, for eight years and counting.

And yet, it is here.

///

Once upon a time in this mama’s child life, there was a boy who exploded with anger, who never wanted anyone to see him cry, even though he was a sensitive boy. This boy worked hard, from a young age, to break free from the grip of darkness.

But there were reasons: there was a dad missing from those most formative years; how does a boy learn to be a man when there is no father to show him? There was a missed-one who called sporadically, making promises that he hardly ever kept; the boy believed them all, because he loved the one who had left, and every time a promise stood broken, the boy crawled deeper into himself, and darkness gained another foothold. There was a mom forced to work multiple jobs just to make ends meet. There were three moves in three years, three starting-overs, three make-new-friends challenges, three learn-how-to-survive-now changes.

One day, when the boy was eleven, he complained of burning pain in his stomach, and his mama took him to the hospital, and doctors found ulcers eating up the belly of a child. His mama called in the troops, a counselor and his teachers at school and the family he loved.

She did her part.

But depression is a tough disease to beat.

///

I know this. I am terrified of it.

I saw the way depression could twist a temper and send it flying out of control. I saw the way it could whisper irrational solutions into the heart of another child. I saw the way it could send a body to bed for days on end. Sometimes forever.

And now, here is my boy, facing this monster.

He comes from a different background than the boy of my youth, but there are still so many pieces in the puzzle of anger turned inward. There is his intelligence, high above his grade level so he feels unchallenged and different and, much of the time, alone. There is his introversion in a house of four, going on five, brothers, where he is hard-pressed to get a word in edgewise, where he can hardly ever find a place of his own. There is his intuition and his sensitivity and his boredom in a traditional classroom and his dreams and his expectations and his behavior and his big emotions and his inability to do anything acceptable, at least from his own perspective. It’s no wonder we are here.

It’s no wonder he has fallen into this pit.

I am scared to death that he will not be able to find his way back out.

///

One day, that once-upon-a-time boy was riding in the backseat on the way to a counselor’s appointment. He was eleven years old, and he already felt crazy, misunderstood, damaged, and this trip proved what he had known all along. There was something wrong with him, something no one could fix.

What if no one could fix it?

He knew the reason he was here: he’d let it slip that he was going to jump off a bridge, and a friend had told. He didn’t know if he’d ever feel like not jumping off a bridge.

And maybe he wouldn’t have really done it when it came down to it and he peered from the top of a bridge and thought about how much it would hurt to fly, but it didn’t matter, at least not that day. Because a mama had seen the look in his eyes, and she recognized it, and she made sure to help him in all the ways she could. Counseling. Time. Love.

///

It was hard to see it, what my son’s psychologist found. My boy didn’t stay in bed for days on end, and he didn’t lose any of his boy-energy. He didn’t cry endlessly or isolate himself or lose all interest in life. He just had a short fuse, and he exploded in anger and acted impulsively when anger got the best of him.

There were days when he would open wide and let a mama and daddy see straight to his soul, where he wrestled with thoughts like No one really likes me and I don’t belong in this family and I should never have been born. There were days when he sat happily with his brothers playing a game of chess or Battleship or Jenga, and he would crack jokes and smile widely and laugh until his stomach hurt. And then there were other days when he clamped tight, and he sat listening to an audio book for hours on end and immersed himself in creating detailed Twister Man comics and bent over his desk putting together and taking apart and putting together again all those LEGO creations.

It didn’t seem all that unusual, but we weren’t looking for depression.

This is the kind of thing that can smack a parent in the face and heart and deep, deep down in the gut—because there was another boy who fell into the pit of depression, pushed from behind by a broken family. And we’re not a broken family, but we’re all broken parents, and what if we caused it? What if our boy never quite recovers because we are still here? What if healing is too far for our love and support and acceptance to reach?

How do I keep him from doing what those others of my past have done?

I don’t know. Maybe I never will.

///

No one else was up that night I was reading in the living room and the boy from once upon a time slid past me into the bathroom that could never be locked because the door didn’t close all the way.

He was eighteen, I was seventeen. It was another year when a dad had disappeared, just after a call had come telling us he’d been in a work accident, trapped under a tractor that had very nearly crushed him, and then there was nothing, for months on end. We did not know whether he was alive or dead. It was a year when a boy would graduate and life waited and he did not know if he was up to the challenge, even though he was brilliant and talented and could have grabbed any job he wanted. It was a year when a boy would be leaving, growing up, becoming a man, and he wasn’t quite sure he knew how.

He was holed up in the bathroom for forty-five minutes or more, and then he walked back out with wraps around his wrists that he tried to hide. I didn’t make a sound, but I couldn’t breathe from where I sat on the blue-flowered couch. I tried to forget what I had seen, tried to concentrate on the open book in my lap, tried to settle what I knew but didn’t want to know.

Still, the tears came hot and thick. I knew what he’d done, what he’d attempted, and hadn’t I tried it myself a thousand times, in more subtle ways—starving myself, going whole days and weeks without eating not just because I wanted to be thin but because I wanted them to watch me wasting away? It was the easiest way for me to die.

This was the easiest way for him to die, too.

Something about depression wraps around an ankle and grows like the silence of an evening. It never lets you go.

///

This is not what I want for my son.

Two months ago, at the height of his behavioral issues at school, his daddy and I found a counselor for him. Every week he sits in a room full of toys and he plays and talks and maybe, just a little, heals. And yet today, when I am sitting in that school room, with all those women who don’t know him like I do, I listen to them talk about helping him through transitions with a timer and providing him a cool-down place for his big emotions, but all I can hear are those words on repeat in my mind.

My son is depressed. My son is depressed. My son is depressed.

What if?

What if he doesn’t beat it?

What if there are darker days ahead?

What if there is suicide?

All these questions can tie a mama in great big, tight knots, but they are the wrong questions for this day, for today. The question today is: What can I do to help my son?

It’s a question without a simple answer. Spend more one-on-one time with him. Pursue a hobby together. Understand and accept and fully embrace him, without changing him.

Sometimes part of beating depression away, for a time, is teaching an eight-year-old boy what to do with his anger, how to rise above it, how to feel it and not be afraid of it, how to crawl all the way through it and stand back up on the other side. If all we’re told is that our anger is unjustified or wrong or unacceptable, we will do the only thing left. We will turn it inward, and the darkness will get another grip on our heels.

He is a boy with anger huddled somewhere deep inside him, and we must do the work of digging it out, letting it out, dragging out that darkness to the light of day. Every day. Every moment. Every encounter.

We cannot just hope it will change. We cannot pretend it doesn’t exist. We cannot hide it. These hearts of our children are worth more than saving face.

And so we sign him up for that extra help at school, and we show up every week to those counseling sessions, and we do everything we can at home to help heal a heart whole.

And there is Another who speaks life into the places where darkness has swallowed the light. There is Another who carries truth into the hearts of men and women and little boys and whole generations. There is Another who lifts their heads and breaks those chains of depression every time they clamp tight. My son knows and loves this Another.

And there will come a day—I know there will—when my boy will beat this disease. It will not beat him—because he has a future and a hope, and it is good and bright and beautiful.

This is enough for today.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Evan Dennis on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

How You Get Lost

listen to them talk

look at their art

read words

find stories

they’re all so good

so put together

so desired

and creative

and sharp

and even though

they’re meant

to be inspiring

what you do

is compare

one life to another

theirs so far

above this one

you have

and somehow you feel

diminished

overlooked

unworthy

like the world

could not hold space

for the both of you

like you will

never be known

for great

let their successes

stop you

this is how

you get lost

How You Get Found

know who you are

know what you love

know the world

needs it

then do it

this is how

you get found

This is an excerpt from This is How You Know: a book of poetry. For more poetry, visit my starter library, where you can get some for free.

(Photo by Amanda Sandlin on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

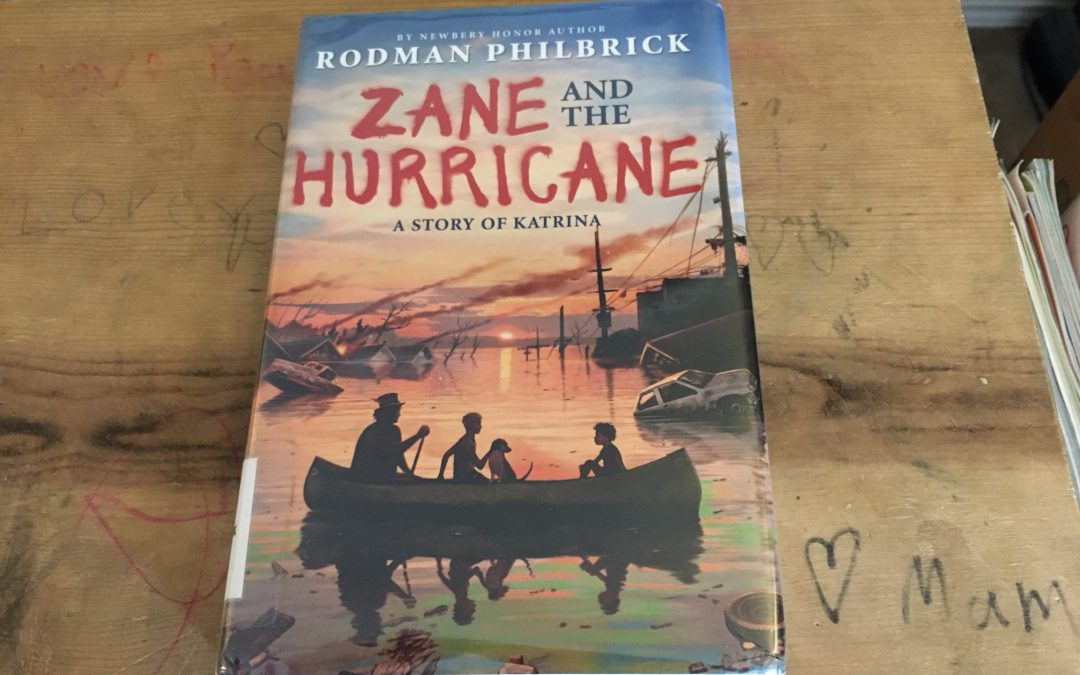

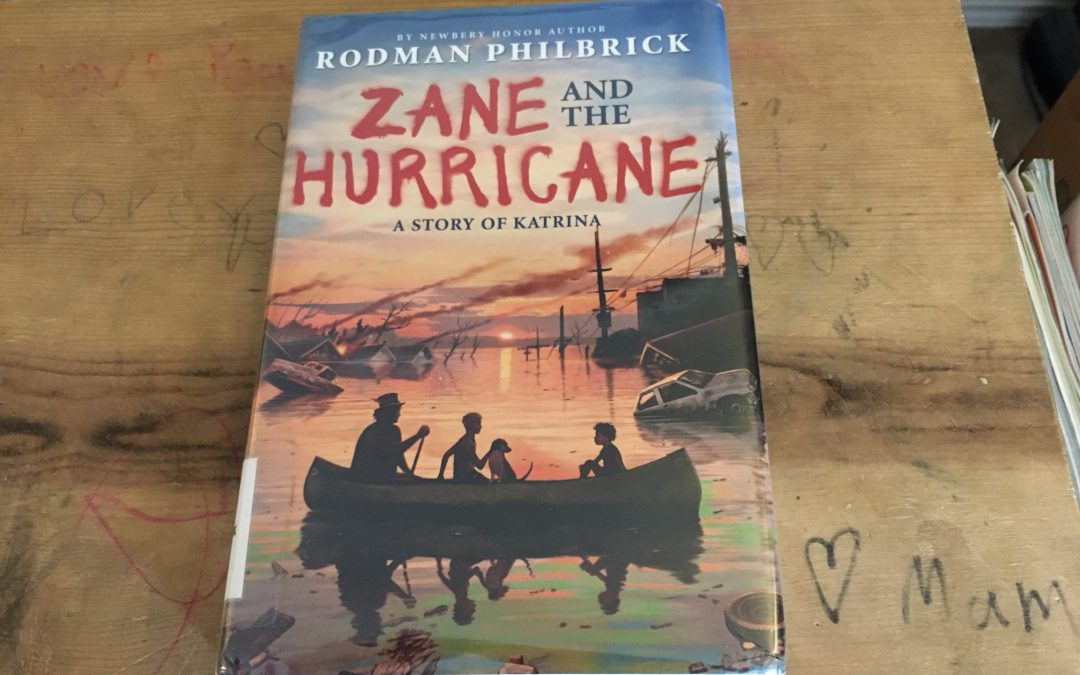

One of my boys picked up Zane and the Hurricane, by Rodman Philbrick, because it was on the 2015-2016 Bluebonnet award list (an award given annually by the Texas Library Association). It looked so interesting that I stole it from him (he was taking too long to read it).

Zane and the Hurricane was a sweet middle grade novel about hope in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. A boy, Zane Dupree, was visiting New Orleans when the hurricane hit, and he experiences the terror of the winds, the loss of electricity, and the massive flooding.

I loved it, like I knew I would.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The characters. Zane was a wonderfully drawn character who had a unique way of thinking and speaking. The other characters were just as well-developed as he was.

The true-to-life events. In the author’s note, Philbrick says that everything Zane experienced happened to at least one of the survivors of Hurricane Katrina. I loved that he used real-life events to weave a story that was so engaging. It was entertaining, but it was also educational, teaching children about the power and horror of natural disasters—and an important part of our history.

The similes, metaphors, and descriptions. Zane had a unique way of seeing the world, as I mentioned above, and that really came through in the book. Take this description of Zane’s great-grandmother, whom he’s visiting in New Orleans:

“The truth is, when me and Bandy first get off the plane and this old lady is waiting there with her two canes, one in each fist, I’m kind of scared of her. She’s so wicked old and the canes look like weapons. Like hitting sticks. This really ancient lady, small and hunched with her hitting sticks. Her skin like the skin on milky hot chocolate when you blow across the top, all wrinkled and folded back on itself. Even her perfume smells like old flowers or something.”

And here is one of my favorite similes:

“One of the cops makes the mistake of saying, ‘It’s only a dog, lady.’ And this woman glares at him like she’s the sun and he’s an ice cube about to melt. “

My son got the book back and is now reading it, too. I think he loves it at least as much as I did.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

There is something frightening that happens when kids start exercising their independence. They start doing things for themselves. Like washing hands. And getting their own drinks. And making their own food.

I say frightening, because what this inevitably does is it makes it ever more impossible to keep a tidy home. Because they will try to get water from the water filter, and they will accidentally miss the cup and make a puddle on the floor, and they won’t clean it up and will forget to tell anyone, and the only way you know about it is when you’re coming in to put the laundry in the dryer, and you slip and nearly die, or at least it feels like you almost died, if your heart has anything to say about it. And then you start laughing, because YOU ALMOST DIED and yet you still have to put the load of laundry in the dryer.

And there’s the bread they’ll try to use for making an after-dinner snack, except they don’t pay the least bit of attention to the crumbs they’re spreading all over the counter and the butter that was smeared into granite so effectively it was rendered completely invisible, and the only way you’ll know about it is when you put the oldest’s reading log on the counter, and the grease starts eating all the way through it and you realize it was only a matter of time before you started looking like THAT family.

And then there’s the washing hands, which usually results in water staying on too long and somehow not keeping to the boundaries of the sink, because they put their hands right up into the faucet instead of leaving enough space beneath it so water won’t splatter everywhere, and there are drops all over the mirror and their shirt. Then, of course, they miss putting the soap on their hands, because they’re not very good at aiming (just look at their toilet) and so every time the faucet is turned on for the next five days, it creates a bubble bath right there in the sink, and you’ll wonder, briefly, how you might be able to save all that soap and to use in their baths or something, except it’s hand soap and good mothers don’t use hand soap to wash their kid, except for that one time you were out of body wash and you thought, what the heck, it’s all made of the same stuff, and you did and the sensitive 6-year-old’s skin broke out and you felt terrible about it. Hypothetically.

Kids come into the world begging for independence. I see it in my infant, who has just started letting go when he’s standing anywhere, so eager to stand on his own and start walking that he doesn’t care that in the next three seconds he’s probably going to fall hard, right on his rump.

And after years of pouring their milk and wiping their noses and dressing them, we start begging for that independence, too (except when our work is gone and then we’ll miss it).

The problem is that independence comes with inconvenient spills that will drip all the way down into a cabinet of storage containers, and you’ll have to go ahead and wash all eight hundred of them. And it comes with snotty tissues lying around the living room, because he thought that when he used them to wipe his nose, you would throw them all away, not him. And it comes with a pile of clothes heaped in front of the closet, because all these shirts were the ones that “didn’t work out” or the ones that were holding on to the shirt he really wanted, and he doesn’t have enough time to hang them back up before school starts.

Independence means pencil shavings spread all over the entryway floor, because the 8-year-old was sharpening a pencil and then the 5-year-old tried and accidentally knocked over the entire sharpener and made the shavings go everywhere, and now the infant is happy that there are more things to put in his mouth. Independence means soap all over the bath rug because he’s just started taking showers on his own, and sometimes the soap squirt doesn’t quite make it in his hand, because he pushes too hard or too soft, but, hey, at least he’s using soap, which is more than I can say for the other third graders, judging by the way their classroom smells. Independence means way too many toys taken out, because he couldn’t decide what to play with, and he can reach all the toys and unlock the door by himself, and so he just chose, in a moment when you weren’t paying attention, to get them all out and save you the trouble. Except he didn’t really save you the trouble.

There are some things that will get worse before they get better, and they can usually be linked to independence.

Food messes are the worst.

When they decided they wanted to have oats with milk for a snack, because they enjoy eating raw oats drowned in 2 percent milk (gross), they thought surely they could do this themselves. I was putting the 3-year-old twins down for a nap and was not aware of their plans. They probably could have done it themselves, except they accidentally opened the bulk bag before taking it off the pantry shelf, and the oats spilled everywhere.

Those are the times you’ll want to take their independence back. Not really. Because I don’t want to be Cinder-Mama. But still. Maybe take it easy on the food, guys.

While it’s easier just to do things ourselves, it’s good for them to feel efficient in their own worlds. It’s also good for them to know that it’s okay for them to make those mistakes, and then learn how to clean them up.

As long as it’s not oats with milk. Or popcorn (no you cannot eat the seeds). Or water from the Brita filter in the fridge. I’ve nearly broken my neck three times, and that was just in a day.

There are some things I’d rather do.

This is an excerpt from The Life-Changing Madness of Tidying Up After Children, the second book in the Crash Test Parents series. To get access to some all-new, never-before-published humor essays in two hilarious Crash Test Parents guides, visit the Crash Test Parents Reader Library page.

(Photo by Jonathan Pielmayer on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Time has been holding my hand these last few weeks.

Not in the way of an intimate friend, but in the way of an impatient parent trying to drag a slow-to-get-ready-child out the door so they won’t be late.

It’s not the last stage of pregnancy that makes me feel so brittle and bruised. Not really. It’s the birthday coming up that I don’t want to mark, because I don’t like marking my climbing age anymore.

I know I can’t possibly always have seen birthdays like this, because I was a really young child once, and every really young child dreams of growing up someday. But for as long as I can remember, I have hated growig older.

It’s not the birthdays, exactly. It’s their number, the way they creep around every year, the way they whisper things like time is running out and you haven’t done enough with the years you’ve been given and you should be further along the writer path than you are today.

Birthdays, for a long time now, have looked down on me in disappointment, tallying up those years and stretching their hand across all my past, as if to say, This is all there is?

Yes. This is all there is. I wanted it to be more, but time was never exactly kind, and days rushed toward dark, and weeks ran toward months, and whole years, when I didn’t really know what I was doing or where I was going or who I even was, slipped right through my fingers.

///

I don’t know exactly when those birthdays began breathing down my neck. Maybe it was the ninth one, when I blew out candles on a ballerina cake my mother had ordered before an instructor told me I was too “chunky” to continue lessons with her; a day when my friends and family all surrounded me except for the one who had missed so many other days like this one; a day when “chunky” got all tangled up around “gone;” a day when I used my wish to say, Let him come home. Or maybe it was the twelfth one, when I stood on our front porch waiting for my whole invited class to show up and only a few did; a day when there was no call or note or card from the missing one; a day when there were no candles to wish upon, because I was too old or maybe she was too strapped; a day when I still made my wish on the first star in the sky: I wish I could be pretty so he would come home.

Or maybe it was the twenty-fifth one, when I had just quit a dream-come-true newspaper job to follow my husband on a church-planting adventure, a day when I decided I would spend my time writing, a day when I peed on a stick and it said yes, a day when I still made my wish on the candles my husband lined up on a cake he’d made himself: I wish I could publish a book.

Maybe it was all of them, because a tenth birthday came around, and he did not come home; and a thirteenth birthday came around, and my beauty, or lack of it, did not bring him home; and a twenty-sixth birthday came around, and I had not published a book.

Birthdays did not feel like friends at all, even to a 9-year-old girl. They felt like fingers pointing to all the ways I had disappointed time.

///

I wish I could say it’s different this time around, but it’s not. The day after my birthday this year, my job will end. It’s the first time I have never worked for someone else. All that space feels more like an expectation, not a possibility. It’s hard to explain, except by saying this: there is a birthday climbing on my back and whispering in my ear, Another year older, and what have you done?

The answer is not much, and so this birthday takes my words and cackles and throws all those other years, when wishes didn’t come true, right back in my face. So when my husband asks if I want to celebrate with friends and family, I say no. Who wants to mark another year gone when there is nothing to show for it?

No published book, still. No job. Not even a family that is “put together” and “doing it” and functioning past the overwhelm that raises tempers and flings at each other words we don’t really mean.

Only an aching back, because kids have pulled all the joints out of whack. Only anxiety that still claws at a neck, even though we’re practicing meditation and exercising and learning to change our thoughts and I’m even popping a pill every day. Only a collection of dreams and wishes that never came true.

///

When I was 8 years old I saw the movie The Goonies (still one of the best movies of all time), and I remember how, for days, I dreamt about all those skeletons. I would sit in the bathtub, and my mom would come check on me, and I would see a skeleton walking through the door. My little sister would be fast asleep in her bed when I came in, and I would see a skeleton lying between the pink sheet and the purple-striped blanket. I would imagine my dad, wherever he was in the world, slumped in a corner, in skeleton form, looking like One-Eyed-Willie, without the treasure waiting on a lost ship.

What I’d seen in a childhood movie had thrown reality at me, proven that one day we would all die, and one day we would all turn to skeletons like the ones Mikey and Bran and Mouth ran into. Death terrified me, because it looked like those brittle bones; sometimes it looked even scarier, like the wax figures lying in a casket. Neither one was what I wanted to be.

When I imagined getting older, I imagined death.

And just like that, a little girl broke off what should be a happy relationship with her birthday. She didn’t want to grow up. She didn’t want to get any older. She didn’t want to die.

///

So, you see, getting older has never been exactly easy for me. I was never the girl who couldn’t wait until she turned 10 or 16 or 21, because every one of those years felt like a step closer to death. And even this week, when another birthday has come and gone, it passed with more dread than excitement.

It’s silly, when we get down to the heart of it, that we fear getting older. We, especially women, can feel time ticking so loudly—this many years until I can no longer have a baby, this many years until my hair turns all gray, this many years until they will no longer think of me as “young.”

What does it really matter?

There is a great gift in getting older, too, a wisdom that begins to settle into our bones when we realize that life is not really about these little things—having a job or not, publishing a book or not, making a name for ourselves or not. Life is really about who we become in all these years. Who we become in our families and in our communities and in our selves.

Will we become people who believe accomplishment and accolades and just-right circumstances tell the whole story of who we are? Or will we become people who believe that our true worth is really tied to who we were created to be, who we already are when we peel away all the layers a world can wrap us in?

We are all born with a diamond down deep inside us, and the diamond is brilliant and visible for a time, and then the world covers it in a great heap of armor, and then we spend the rest of our years trying to uncover it again so we can see and know and believe the treasure we already are, without the qualifications and accomplishments tagging behind our name. And if getting older means uncovering more of that brilliance, one shovelful at a time, then I want to embrace age. Wisdom. Maturity.

So this year, on my day, I didn’t check for more gray hairs and moan about the wrinkles that have begun to gather around the corners of my eyes from smiling too much at my boys. I looked, instead, toward the gift that time holds out to me every single birthday: one more chunk of a diamond revealed.

And then I whispered my wish.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Poetry

Pants

Finding a good book

is like putting on comfy

pants. Everything fits.

Reading

The day was perfect

for traipsing around, reading

a book’s lovely truth.

Stories

My favorite time with

children is the magical

hour of stories.

These are excerpts from The Magical Hours, a book of haiku poetry. For more of Rachel’s poems, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of volumes for free.

(Photo by Jessica Ruscello on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Books

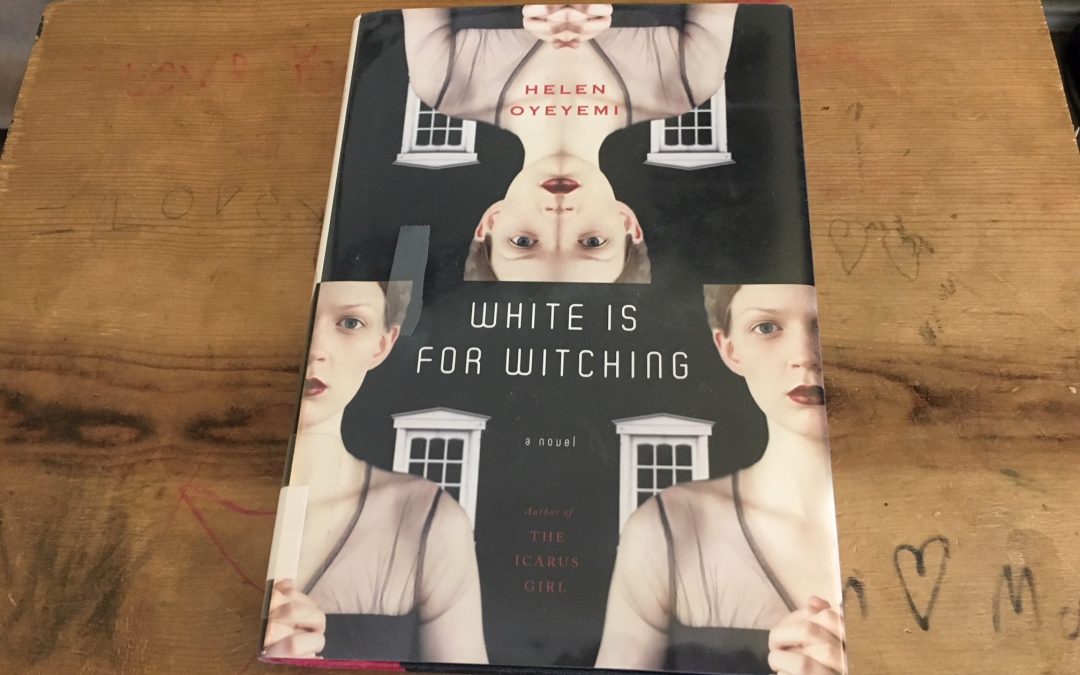

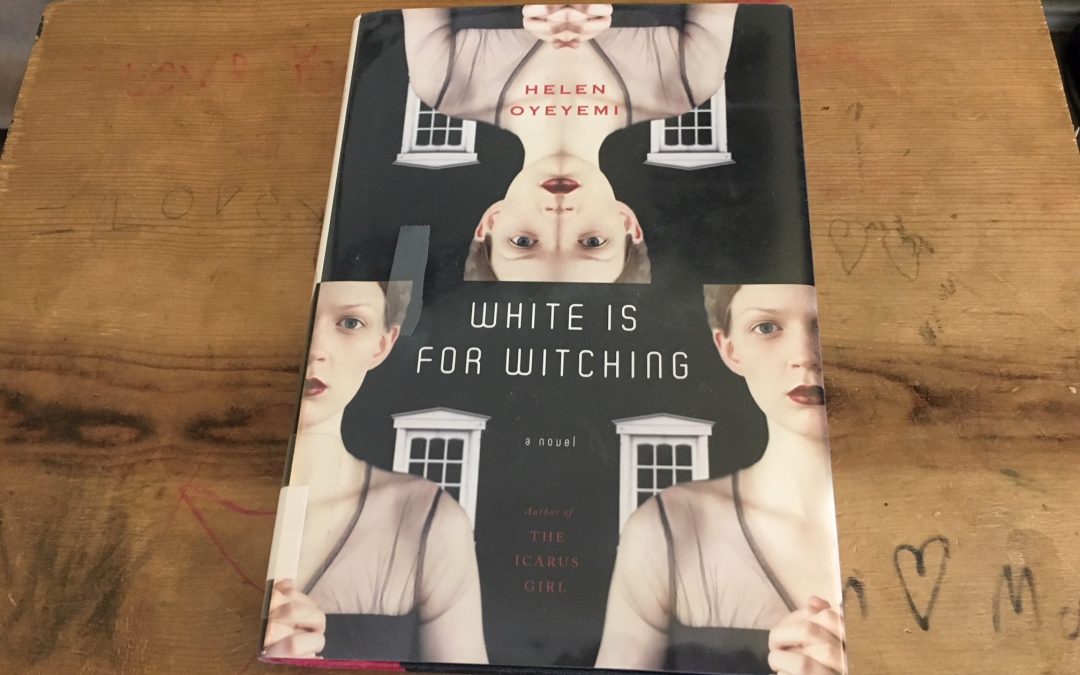

I’ve been doing some exhaustive research on mental health issues, depression, suicide, and mental institutions, and White is for Witching, by Helen Oyeyemi came up on my search for best books to read.

And it was fantastic.

The story is strange, creative, unusual, and interesting—yet another book I have no idea how to characterize. I’d call it an adult literary novel that examines madness and has a fantasy/horror feel to it.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The opposing viewpoints. Oyeyemi used different points of view to distinguish between the characters telling the story (first person, third person). All the characters were unique and interestingly strange in their own ways, all descending into their own forms of madness in very individual ways. It was fascinating. There were even some sections of the story told from the house’s viewpoint, which lent the novel a creepy sort of feel.

The unusual classification. The focus on characters would classify this book as a literary novel, but it was also unlike other adult literary novels—was it horror, or was it fantasy? I love books that break the rules, and this one certainly did.

The art. This was truly a book that I would qualify as art. At certain sections in the book, one point of view would finish with the same line that would begin another point of view, like a long narrative poem was unfolding before the reader’s eyes. I found it delightful.

Here are the brilliant opening lines:

Ore:

Miranda Silver is in Dover, in the ground beneath her mother’s house.

Her throat is blocked with a slice of apple

(To stop her speaking words that may betray her)

Her ears are filled with earth

(To keep her from hearing sounds that will confuse her)

Her eyes are closed, but

Her heart thrums hard like hummingbird wings.

Does she remember me at all I miss her I miss the way her eyes are the same shade of grey no matter the strength or weakness of the light I miss the taste of her I see her in my sleep, a star planted seed-deep, her arms outstretched, her fists clenched, her black dress clinging to her like mud.

She chose this as the only way to fight the soucouyant.

Eliot:

Miri is gone.

White is for Witching was probably one of the best, most interesting adult novels I’ve read in a long time.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test Parents

The beginning of every year is a time in which goals, resolutions, our new ways of being—whatever you want to call it—have strong and resilient roots. Husband and I spend the last couple of weeks of every year goal-setting, because we believe it’s important to start the new year with a frame, even if that frame is dismantled within the first few days.

Which is generally what happens to our parenting goals.

This is mostly because children are so adept at taking our goals and shoving them. I’m convinced they make goals of their own, and this is what that process looks like:

We say: No more yelling.

They say: So much more yelling.

The first day of the new year is welcomed with such high hopes. We hope that we will be able to get through an entire day without yelling. This is our hope every year—mostly because we think the kids are another year older; surely they’ll be able to (a) tone down the noise and (b) stop making us so mad.

Nope. They try even harder. Not only that, but they’ve resolved to yell more themselves, which means when we’re having chicken (always a win) for dinner, but they don’t get seconds until they eat their spinach salad (never a win), they’ll yell about how unfair it is that they have to eat such disgusting stuff. When it’s time for baths, they’ll yell about how all their friends are still out playing. When their technology timer has clanged and they’re not finished with the game, they’ll yell about how we’re the worst parents ever because we put a limit on how much time they spend rotting their brains in front of a screen.

We say: This year we’ll eat fewer sweets.

They say: This year, we’ll sneak more sweets.

I’ve tried so hard to get rid of sugar in my diet. I’m not supposed to have it; it’s something that could cause heart disease for me, because I have a gene anomaly that prevents my digestive system from processing sugar anywhere but hips, thighs, belly (you can tell I have a hard time with this goal), and, more importantly, my (invisible) triglycerides.

Unlike me, my kids will find every opportunity they can to cram more sugar into their mouths. You’ll see evidence of this at holiday gatherings, when they hover around the dessert table hoping I don’t notice that a finger slid into the perfect lemon pie. You’ll see it at birthday parties, when they smuggle extra brownies while leaving a trail of crumbs on the floor that lead to their hiding place (at least they can find their way back out—if they can untangle themselves from the clothes mountain in their room). You’ll see it at school, where they’ll swipe an extra cupcake for their friend’s birthday—hey, it was free!

If we could all be so immune to sugar.

We say: More happy family moments.

They say: We’ll see about that.

So much of my life is about getting things done. Wash the dishes, fold the clothes, cram in a few hours of work. Husband and I both work from home, and it’s easy to let that work bleed into our every-day lives. So we always have this goal on our list: to soak up more happy family moments, without work-creep and rush, rush, rush.

The problem is that kids are kids. They’ll take three hours to tie their shoe, because they wanted to do it themselves. They’ll decide the tie they have, which they aren’t supposed to have, isn’t quite the right color and will spill all the ties (which, again, they aren’t supposed to have) all over the floor and think the Cleanup Fairy will take care of the mess. They’ll destroy the toilet and, by default, the bathroom walls, when we’re already half an hour late to church.

So much for New Year’s goals.

The other day, I walked into the kitchen, and one of my 5-year-olds was cramming a brownie into his mouth as fast as he could because he thought I was otherwise occupied. I almost said something, but, instead, I let him think he got away with it.

I may as well let someone in this house meet a goal this year. Because it’s certainly not going to be me.

(Photo by Jerry Kiesewetter on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Recently I talked with a group of third- and fifth-graders about how to cultivate creativity in a young life, and one of the first questions they asked me was this one: Who were your biggest influences when you were a kid?

I hadn’t pre-prepared for any of the questions they asked me, even though I should have known they would come. Kids are curious about what (and who) shapes adults to become who they are. And there were so many influences along my journey—but what they all had in common was that they were authors. This is because, even as a child, I was a reader. A writer. A girl who knew what I wanted to be before I ever had a clue what it meant to be grown up.

During a recent year of writing poetry based off the words of famous writers, artists, and influential people, I stumbled across this quote from Francois Mauriac, a French novelist, dramatist, critic, poet, and journalist: “Tell me what you read and I’ll tell you who you are is true enough, but I’d know better if you told me what you re-read.”

These words ring true in my life.

There are so many good things to read. I read mostly middle grade fiction, more young adult fiction recently. I read a poem a day from various poets. I read some adult literature, but not much. I read the classics.

What I re-read is a much smaller list, but it points to who I am. The most re-read book on my shelf is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, followed closely by Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, Rilke’s collected poetry, Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and Something Wicked This Way Comes, everything Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison have written, and Katherine Applegate’s Home of the Brave and The One and Only Ivan.

Though we rarely recognize it, books shape us into who we are. We spend hours, days, sometimes even weeks with them, and we are always changed by the end of them. And the ones we re-read change us even more.

Books offer us new ideas, tell us who we might be, open us to the lives of other people who are different than we are.

They show us a way forward. They prove that we can overcome, we can do better, we are made to be heroes of whatever story we’re living. They remind us that this—the shadow we’re wrestling with right now—is not the end of the story.

These are all the things I love most about books.

So as we begin a new year, I want to encourage you to find more time to pick up those books stacked on your shelf. Sort through the list you’ve been keeping in the back of your mind. Read one more book a month than you did last year.

And then re-read it. Let it teach you fully what it has to say.

I’ll be doing the same.

For more writings like this (and exclusive book recommendations, first looks at writing projects, and much more), sign up for Rachel’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also get a few free books while you’re at it.