by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Another of my boys starts school next week, taking that first step on a 13-year journey, and there are three of them now, away from my influence seven hours of every weekday, and I can feel the fear of it catching in the back of my throat.

It happens every year, just like this, and every year I have to fight off that failure-feeling that sneaks in—because I cannot be a homeschool mom.

I could protect them from so much. I could drill those values so deep in their hearts they’d never get them back out. I could speak life into their lives all the time, instead of relying on a behavior chart to teach them who they should be.

I could control their friends and their food and their learning and their choices and their decisions and their opportunities and their playground interactions and their exercise routines and their literature reading and their library visits and the soap they wash their hands with and the way people around them talk.

My heart has begun its jagged beating, once more.

I wish. I wish. I wish.

///

My first day of kindergarten I walked into a classroom not much bigger than a dorm room, lit by lamps and a back wall of windows. Mrs. Spinks hung all those alphabet balloons, an apple with an A, a penguin with a P, a zebra with a Z, in every corner of the room, and she pointed, three times a day, to the checkered carpet sitting in the center of the room, where we’d learn our letters and their sounds, even those of us who already knew how to read because our mama was a librarian and our 10-months-older brother had come home every day from his kindergarten year and taught us everything he knew.

My brother had refused to sit in that neat circle on a checkered carpet the year before, but I did everything I was told, eager to please in any way I could.

Just after lunch, the room transformed into a blue-carpeted mat, because we all stretched out our nap pads, and Mrs. Spinks would turn on that big noisy fan and all my classmates would sleep around me while I stared, wide awake, at those bubble letters, creating elaborate stories in my mind that linked them all, the zebras and the penguins and the apples and everything in between.

In that room we colored and slept and sat at desks facing a chalkboard with no computer anywhere in sight, and we were such a small town everybody’s parents knew everybody else’s parents, and we, the students, had already known each other for years.

It was safe. Comfortable. Warm.

///

Four years ago, when the oldest started school, the whole family walked him into a room with desks facing each other in pods and math sums arranged on posters and stacks and stacks of handwriting pages he and his classmates would work through by the end of the year, because all those 5-year-olds, or most of them, already knew their letters and just needed some extra practice writing.

My boy didn’t seem to notice that day the proximity of those desks, how they never gave a student one minute to be alone, but he would, in unexplainable ways, notice them later, when he’d yell at his brothers to leave him alone and when he’d cry about things he never cried about and when he’d fall asleep on our bed, even though he hadn’t napped since he turned 4.

I wondered, a hundred times, a thousand, if we had made the right choice.

But I worked a job, and that made homeschool a can’t-do option, and all those kids still at home, four of them, made it an even greater impossibility.

In those first days, I did what most first-time-public-school mothers do—I wrote a note to his teacher to explain my boy’s little quirks, the way he preferred to take off his shoes after playing outside because he wanted his toes to breathe, how he enjoyed teaching himself and read animal encyclopedias and Harry Potter and environmental guides, how he loves hard and strong and wild like a tornado that’s often overwhelming for those who are the recipient of that love.

I wanted her to know him the way I did, and I wanted her to accept all those quirks, all those strong-willed bones that hold a hard line in his body, and love him anyway.

And then we walked our beloved one to school and left him there, sitting in a seat that bore his name. I hoped all the way home that he would feel as safe as I did when I was just a 5-year-old girl in a world I had never known.

But you can’t make a teacher love a child, and sometimes the only safe place you can give him is his home-place.

I would learn that later, and it would drive another spear in my heart.

///

The kindergarteners in my small-town school shared a playground with everyone in school, just like we shared a cafeteria with one lunch period and one tiny hallway of classrooms.

Our playground didn’t look at all like the playgrounds of today. A merry-go-round and a metal slide and three seesaws edged it, and, in its middle, a bank of swings and above-ground culverts and cut-in-half tractor tires painted sky blue and electric orange and pale yellow, set upright for the climbing onto and under. A cement slab waited across the street for P.E. class, but we weren’t allowed to cross the street during recess.

That first day I stayed far away from the seesaws and the merry-go-round and the tires. I stuck to the swings, because it was what I knew, and I could kick my feet high and feel like I was flying for that half-hour of free time twice a day.

It was safe.

But as the weeks wore on, I watched friends climb through the above-ground culverts, where spiders hung from cement tops and snakes might be hiding in the grass patches between them—and if they could do it, I could, too.

A friend and I hid in one of those culverts during one recess, and there was a boy, years older, who stood just to the side of it. I knew who he was—a big boy who rode the bus home with my brother and me—by his scratchy voice.

Hey, Fatton, he yelled so everyone on the playground could hear. I peered out of the culvert, because the name sounded awfully close to my last name: Patton. He was pointing at my brother, just across the way, climbing onto a seesaw with a friend small and thin. You’re too fat for that, Fatton.

He wasn’t fat, my brother, just solid, built like a football player, but the name would stick all through elementary school, and that boy would be the torturer, and he would drag along with him other boys, boys who went to church with us and boys whose moms knew our mom and boys who came from good homes with a mom and dad who loved them and tried to raise them right. They would all tease and poke and tear apart.

It was that day I learned that school could be a not-so-safe place, one that could take a last name, Patton, and turn it into Fatton because someone thought it was funny and didn’t think through how it might brand a heart forever.

///

It’s not so different, this world where my sons will walk to school and sit in a classroom and play on a playground. And yet it’s so very different. Bullies existed back when I was a girl, of course they did, but we knew each other’s parents and we knew each other and we didn’t hide behind technology and computer screens and entertainment that existed outside of real relationships with real people.

We knew how to look our tormentors in the eye. We knew how to see that their mom was dying of some disease doctors didn’t know how to cure and how his dad worked too much and never spent time with him and how they were afraid of our brains and our dreams because they somehow believed ours stole something from their own.

My boys, though, are coming of age in a world that values performance over empathy, that holds up competitions as the only way to achieve, that mandates boys walk angry and wounded and shut down, because to show emotion is to be a lesser man, and they don’t know how to express their deepest hurts outside of the violence they see everywhere—in games, in movies, in their homes.

They will live in a school world where men can walk in and shoot 5- and 6-year-olds, where boys carry knives in the front pocket of their backpacks, where bullies on playgrounds can rip holes in a heart faster than a mama can mend.

How does a mama keep her sweet boys safe in a dangerous place like this? How does a mama make sure her boys keep holding tight to who they are in a culture that holds up who they aren’t as the “way to be a man”? How does a mama breathe on a day like today?

These are questions I cannot answer.

///

All the kids braved the monkey bars back when I was a girl, even though they were so high off the ground even an adult had to swing across instead of walking themselves across.

There was a day when I watched a boy, my brother’s best friend, get halfway across and then drop, his body twisting all the way to the ground, his hand trapped beneath him so it cracked in three jagged pieces. I watched him turn pale as the teacher on duty led him away, and I watched him return five days later with his hand and wrist wrapped in a white cast, ready to sign.

I watched a friend brave the big metal slide that burned our behinds raw when the sun was out, and she slid all the way down, her legs squealing for her, and then her bare-skinned thighs stuck to the bottom so she had to throw herself off, and the throwing knocked out two front teeth before they’d even had a chance to loosen. I watched her cry herself bloody as she ran off to find help.

And then there was another day, when we all sat in a cafeteria where the smell of chicken noodle soup shifted and turned and stretched, and I sat down with my friends and dipped my two cheese rolls in broth and ate them first, and then I heard the yelling, and there was my brother, turning blue, and Mr. Tegler, the district speech therapist, behind him, lifting and squeezing until that bone flew out of his throat and my brother sucked air like it was all he’d ever wanted to do. I watched his face whiten in the relief of breathing again when he thought he never would.

My brother could have died. He could have died. He could have died. That’s what I remember thinking all those days later, a childish sort of thank-you prayer. A help-me prayer too.

Because in a place this unsafe, anything could happen to anyone.

///

My sons could die. My sons could die. My sons could die. Every step closer to the school, I feel those weights closing in.

How do I protect their dreams from death? How do I protect their hearts from death? How do I protect their lives from death?

I could drive myself crazy with all these questions I cannot answer. I can twist and turn under that not-really-a-decision public school decision, all those fears it drags along beside it, and I can let its guilt nip my heels all the way through the halls to those classrooms, and I can feel its burden hanging my neck and dragging my feet and choke-holding my heart.

Or.

Or I can let them go, let them take this first step out of my arms, because there will be so many more that must be made after this. I can loosen my hold to their own capable selves, to a God who knows them better than I know them myself.

We are parents, and we will always hold them tight, in arms or in ragged raw, letting-go hearts, but there is Another who holds them, too, and as hard as this letting go is, we must remember they will be caught. They will be held. They will be loved.

I can keep them hidden and safe, or I can let them go to shine like noon in a world of midnight.

I can keep them within the bounds of my home and my carefully controlled community and my list of approved friends, or I can let them go to stand on legs of their own and live out values and missions and love in their own individual way.

I can teach them to crawl in my safe-zone perimeter, or I can let them go fly.

I want to be brave enough to let them fly.

So next week I will take the first step. I will swallow hard, and I will kiss them goodbye, and I will whisper those words into their ears, Remember who you are. Strong. Kind. Courageous. And mostly Son, and then I will walk the sidewalk back home, with three more who wait for this flying.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Is it better to self-publish or traditionally publish? Well, the answer is both. But it depends on the project.

Here’s a guide for the pros and cons of publishing, as far as what I know today.

1. The book release.

In traditional publishing, someone else takes care of the book release. With self-publishing, it’s all up to us.

This is a big one, for me. Right now I’ve released 16 books, and each of them probably took a total of about 30 additional hours to complete, beyond the writing part. Those hours were spent on things like fine-editing, writing book descriptions, getting them uploaded in all markets, writing marketing material, compiling them for print. If we don’t enjoy the technical side of the equation (I’m don’t!), self-publishing can seem daunting.

It’s not easy learning all that needs to be learned in order to self-publish. It’s also not quick. It’s an investment of our time, in our business. Our first few releases will take much longer than the ones that come later, because the learning curve is pretty high. But once we learn it, publishing will get much easier.

Of course, with traditional publishing, we don’t have to worry about learning any aspects of publishing, because someone else does it all for us (except for marketing. But I’m getting ahead of myself).

2. Book elements.

With self-publishing, we have more control over all the elements of our book. This would be anything from the revision process to the way the cover looks. In traditional publishing, we don’t get to pick things like who we want to design the front cover of our book. I can’t go to an agent or an editor and say, “Hey, my husband designs book covers, and I’d really like him to design this one.” Nope. They have their own people in mind.

But I can do that when I’m in charge of all aspects of book publishing.

Now, the downside to this is that if something is off—if the cover isn’t perfect but we think it looks great (because we don’t really have much expertise in design), we won’t know except by sales that just aren’t there. If there’s a typo in our book, it’s up to us. It’s not up to an editor at a publishing house.

That can feel like a lot of pressure.

When I was about to publish my books, I had a really hard time releasing them. I sat on them for weeks, because it was just so scary to release something on my own, without the benefit of having lots of eyes (agents, editors, book designers) who may have found a glaring mistake that I missed after looking it over a hundred times. Unfortunately, readers are not as forgiving when it comes to book errors if you’re a self-published author. They’re much more forgiving if you’re a traditionally published author, because they know it’s probably not your fault.

So if you’re going to self publish, the manuscript should be as close to perfect as it’s ever going to get.

3. The revision process.

In self-publishing, we have full control over the revision process. This can be a good thing. Who wants to spend years and years on a book, only to hear that someone thinks it would sell better if we took it out of first-person point of view even though we disagree? On the other hand, what if that information is correct, and we don’t have someone telling us?

As self-publishers, we have much more control over the revision process of our manuscript, but we also lose that contact with other people who really do know what they’re talking about. A middle grade novel I wrote is currently in the revision process with an agent, because she noticed something that could have added depth to the book. And she was right. I’m so glad she pointed it out. If I were just self-publishing the book, I might have missed adding that layer of significant meaning to my book.

And every time I get a revision request for a manuscript, I learn something new that I can apply to my self-published titles as well (which is why I enjoy being a hybrid author).

4. Marketing.

Unfortunately, there’s not much difference here between self-publishing and traditional publishing. Publishers no longer take care of advertising and marketing for their published authors, so you’re on the hook for building your own platform, either way you decide to publish.

5. Distribution.

National book sellers (the non-virtual kind) will not acquire your book unless you’re published through a traditional publisher (or unless you become a best-selling self-published author, which is possible, but not statistically likely). If you’re self-published, you can get those titles online as ebooks (and also pay to have them sent to people who might want to have a hard copy—but your margin of profit is much smaller on those), but you will never see them on the shelves of book stores and libraries across the nation without a significant amount of marketing dollars and work on your part. And usually not even then.

Some people think that bookstores will be gone in the future, and we’ll just be buying books online, so maybe this doesn’t even matter. I like to think bookstores will be sticking around, and I want to have at least a few of my books on their shelves. So I’ll keep trying for traditional publishing.

6. The representation process.

The representation process tied to traditional publishing can take a really long time. Years for some projects. Sometimes this is enough of a negative in itself. To research a handful of agents who might like my book, produce a query letter, ready the manuscript for submission and write a synopsis probably took about 30 hours start to finish. I’m not guaranteed a return for those hours like I am if I just self-publish and spend those hours writing marketing copy. And then it’s a waiting game from there. I’ve been sitting on my middle grade novel since January, still waiting to hear if two different agents want it.

7. The feeling of accomplishment.

I’d say this is the same for both. While it’s really encouraging to have someone interested in your book, to let you know that it’s not just you who thinks it’s pretty awesome, it’s also very satisfying to see your book in print and know that you did it ALL. So, either way, it’s a win.

8. Let’s not forget money.

As a self-published author, I get to keep much more of my profit (when I’m not giving books away for free). I can also give books away for free, if I choose to. In traditional publishing, you’ll get an advance (a sum of money that will “pay” for the writing of your book—usually not much if you’re a first-time author). After that advance, you won’t get any money until the publishing house recoups the publishing and distribution costs. So it could be a long time before you see any money from that. And even if you start making sales money again, the publishing house takes a cut, and so does your agent.

Of course you don’t get to keep all the money from self-publishing either—about 70 percent or less of the price of your book, because places like Amazon and Barnes & Noble have to pay to have your books displayed and included in search engines. But what you make, percentage-wise, is much more than you’d make publishing traditionally (only about 3-5 percent).

Now it’s up to you to decide: self-publish or traditionally publish?

Week’s prompt

Write as much as you can, in whatever form you want, on the following word:

Radio

by Rachel Toalson | General Blog

Left kid: I’m going to write a story. It’s going to be about [talks for the next 10 minutes.]

Right kid: I wish I could color your mouth shut.

Right twin: I was gonna feed my sunflower seeds to the ducks, but Mama said no. I have to eat them.

Left twin: Oooooh! You said but!

Left kid: This game is so cool.

Right kid: SCREEN!

Front: I wonder what we’re having for dinner.

Middle: Pssst! I figured out how to pick the lock on our door with a plug prong.

Back: Better not tell Mama!

Right: You’re an interesting creature. What do they call you?

Left: Someone please get me out of here.

Him: I just love the smell of my own fart.

Him: My brother just took away a red LEGO and now I can’t build what I need to build b/c there are only five billion more red LEGOs and also the world is ending.

Left kid: You have a really nice booger in your nose.

Middle kid: If you only knew what I just did.

Right kid: I REALLY NEED TO PEE!

Thing 1: Is she still behind us?

Thing 2: Yes.

Thing 1: Think we could slip away without her noticing?

Thing 2: Probably.

Left twin: We ate a whole bottle of kid vitamins.

Right twin: If you only knew what I’m going to do to the toilet later today.

Him: Don’t worry. I just fell asleep while I was talking, too.

And, a special bonus:

by Rachel Toalson | Books

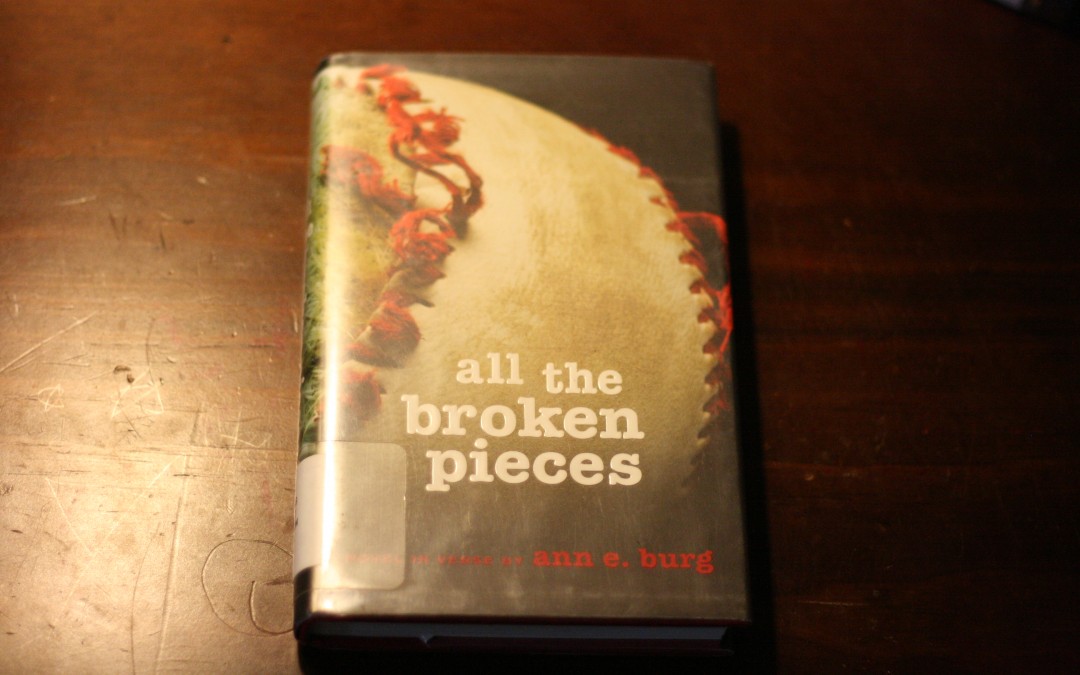

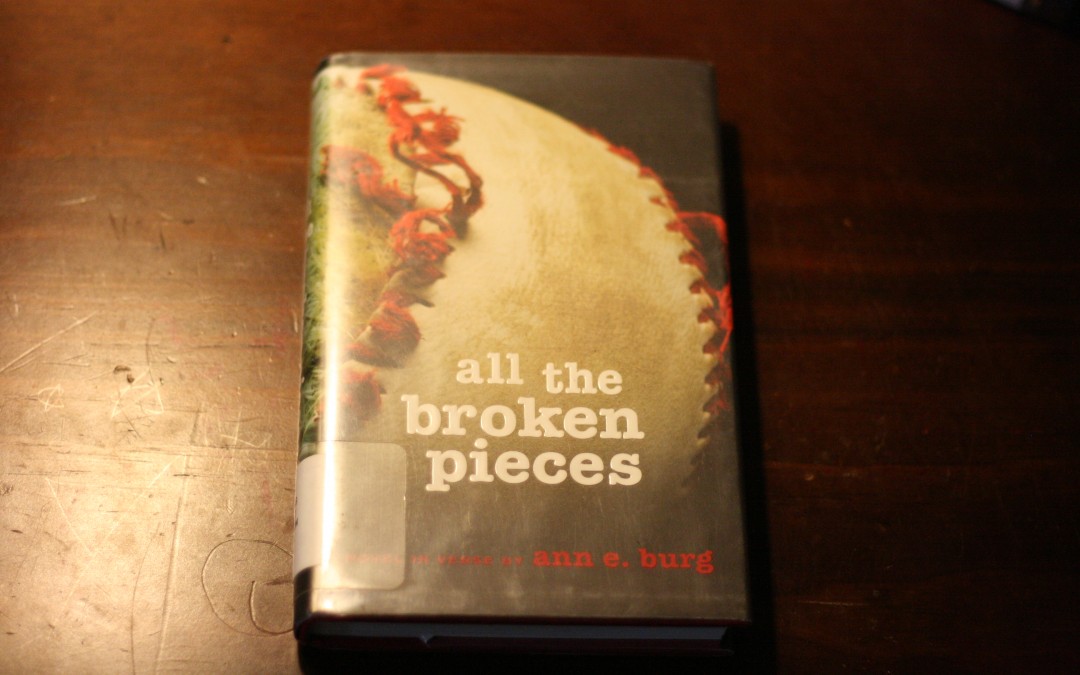

If you’re looking for a great young adult read, look no further than All the Broken Pieces, by Ann E. Burg—an award-winning young adult novel written in poetry that was just beautiful.

I picked up All the Broken Pieces because a book I was reading mentioned it. I’m a sucker for books written in verse, and when I saw what this one was about, I knew I had to add it to my list. Usually, when something gets added to my list, it takes me a while to get to it, but novels in verse have a little bit more priority.

All the Broken Pieces is about a boy named Matt Pin who comes to live in the states after suffering some of the horrors of the Vietnam War. He carries around scars that he tries to keep hidden, because they’re shameful and frightening and too horrible to speak aloud. Throughout the book, Matt is faced with discrimination, the flare of his memories, fear of abandonment and loneliness created by the secrets he tries to keep inside. But he is forced to confront his nightmarish past and choose between blame or forgiveness and fear or freedom.

This story was only about 22,000 words, which is short for a young adult novel, but it was full of hope and heart and history—proving that you don’t need a whole lot of words to write a beautiful book. That’s probably what I loved most about it.

Burg employed a sort of mystery around Matt’s past that kept a reader engaged and interested in what was going to happen to Matt. There was also some tension on his baseball team when a boy told Matt that his brother died in the war because of Matt. The words, “My brother died because of you” are never easy words to hear, and Matt believed his teammate for a time.

Matt is an endearing character—readers feel sorry for him and yet we also root hard for him, because we love him and his innocence and his sadness. All the Broken Pieces was Burg’s debut novel and was beautiful, harrowing and an important contribution to the young adult genre.

Here’s a passage that demonstrates the mystery Burg wove around Matt’s past and also the lovely cadence of her language:

“I have a new brother.

He doesn’t look like me.

I’m too much fall—

wet brown leaves

under a darkening sky.

Tommy is summer—

sunlight, peaches,

wide, grinning sky.

Even Tommy’s hair is summer.

Curls cling to his scalp like

the yellow-and-white sweet corn

at McGreevy’s Market.

Only one straight tuft sticks up,

like a clump of sun-scorched hay.”

Matt feels tension in his surroundings—the difference between America and his home, as you can see from this passage:

“There re no mines here,

no flames, no screams,

no sounds of helicopters

or shouting guns.

I am safe.

How can I

be home?”

And, lastly, here’s a passage the demonstrates the complex character we have in Matt, as he tries to describe what Vietnam is to him now.

“My Vietnam is

only

a pocketful

of broken pieces

I carry

inside me.”

I hope you enjoyed these book recommendations. Be sure to pick up a free book from my starter library and visit my recommends page to see some of my favorite books. If you have any books you recently read that you think I’d enjoy, contact me. I always enjoy adding to my list. Even if I never get through it all.

by Rachel Toalson | Messy Mondays

It’s a celebratory day when kids are able to buckle their own seat belts and pour their own glasses of milk and bathe themselves and cook their own food (wait, when does this happen again? I’M READY ANYTIME, KIDS).

When they’re little, we spend so much of our days doing every single thing for them that every tiny little mastery feels like a major victory.

But in order for them to learn how to do things for themselves, in order for them to achieve autonomy, there is this frightening limbo between beginning and mastering when we must let them practice.

I say it’s frightening, because I know. Here’s what working toward autonomy looks like in our home:

Pouring milk

The 8-year-old: Check the level on the milk. If it’s less than half-filled, overcorrect, because you got this. If it’s too full, try anyway, and spill a whole ocean where you can let your Lego man swim before you try to clean it up. And by cleaning it up, you mean wiping it toward the floor so it soaks not only the counter but inside the drawers and cabinets, too. Conveniently forget to clean up the spills you can’t see so your mom will find it—not with her eyes, but with her nose—three days later.

The 5-year-old: Only pour from a gallon that is less than half-filled, because you’re careful like that.

The 4-year-old: Pour anytime you feel like it, but do it from the floor. Wipe up the mess you’ve made with a paper towel but no cleaner so the stickiness will steal someone’s socks tomorrow. Laugh hysterically when it does.

Tying shoes

The 8-year-old: Tie one, and then get really frustrated when the other one doesn’t tie as easily because everyone is talking. Tell everyone to be quiet so you can concentrate and then try again. Tell them to quit looking at you. Make three good attempts, and then take off your shoe that just won’t tie today and throw it across the room. Say you’ll go to school with only one shoe on. You don’t care. Change your mind five minutes before you’re supposed to leave, after you’ve forgotten where the offending shoe landed when you threw it. Your dad will find it and help you put it on. Unless you call him a git (British term, mildly derogatory, made popular by Harry Potter. Means “a foolish or contemptible person).

The 5-year-old: Don’t even try. Your mom will do it.

Packing up

8-year-old: Look in your room for your agenda. Complain that you can’t find it, even though it’s sitting just beside your desk, right by the four thousand Lego pieces you dumped out last night and “forgot” to clean up. Say it’s gone forever. Say someone must have stolen it. Say you’ll never be able to write down your school assignments again. Ever. Say “You must have moved it,” when your mom comes downstairs with it.

5-year-old: Let your mom know you can’t find your red folder, then laugh when she pulls it out from under your lunch box, the same place it always is in the mornings, because it’s waiting for you to pack it up.

Sweeping the floor

8-, 5- and 4-year-olds: Only sweep a square area of four tiles across and four tiles down. Don’t even try to get under the table, where all the food is. It’s too hard, and your knee is hurting. You think you might have broken it.

Wiping the table

8-, 5- and 4-year-olds: Push all the extra food to the floor by the sponge. Be sure to leave streaks all over the table, because you didn’t want to use the cleaner, OR leave a lake because you had a little too much fun spraying the cleaner and the sponge is too soaked to absorb anymore.

Doing dishes

8-, 5- and 4-year-olds: All the silverware must fit into as few slots as possible, even though there are six slots and three that are still empty. There is no rhyme or reason to putting dishes in; just throw them randomly in whatever space is available. After all, the dishwasher is like a car wash for plates and bowls. Don’t worry, Mama. It’ll all get clean.

Putting laundry away

8-year-old: Hanging clothes don’t have to be hung up, exactly. They can be stuffed into the underwear drawer, because it’s not full, and all the other random empty drawers in the room.

5-year-old: Don’t pay attention to the labels your mom put up in the closet. Just put your clothes wherever you feel like putting them, even though you share your closet with two other brothers. That way, when you dress for school, you’ll have a legitimate reason for dressing in a shirt two sizes too large. “It was on my side,” you’ll say.

4-year-old: Get mad trying to hang up shirts, and throw your hangers across the floor so some of them break and your parents will help you hang up the rest.

2-year-olds: Rearrange (and by rearrange, you mean empty) the pajama drawer eight times a day because your parents let you put clothes in it once.

Putting on shoes

2-year-olds: It doesn’t matter if shoes don’t match or if they’re different sizes. Just put them on. Shoes are shoes are shoes. Stop trying to match them and put them on the right feet, parents.

Cleaning your room

8-year-old: Make sure all the books that are supposed to go on the bookshelves in your room end up on your bed instead. That way your mom won’t be able to find the library books when they’re due. Push everything else in the closet and shut the door. You don’t need the closet anyway, now that all your clothes are stuffed in drawers.

Bathing

8-, 5- and 4-year-olds: You really only need to wash your hair, your belly and your feet. Everything else is already magically clean.

Dressing

8-year-old: Who cares if the sweatpants you’re wearing aren’t yours but belong to your 2-years-younger brother and look more like capris than pants? They were in your room, stuffed in a drawer, so they’re obviously YOURS. Make sure you leave your pajamas on the floor so they won’t make it into the laundry and you can complain two days after laundry day that you don’t have any more pajamas. Also, make sure you forget to put your shoes on before getting in the car, because you just know there’s a pair in the car (there isn’t). And don’t check to be sure until you arrive at your destination.

I know that eventually they will get good at all this, because practice makes perfect.

Right?

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Today I had a song stuck in my head, one from Plumb’s CD Need You Now. The line from the song goes like this:

“But I’ve never felt this tied up and helpless/and all that I know is you’re gone, how do I let go?” and when I’ve finished singing it, I have this from my 4-year-old: “The singer wasn’t really tied up, was she?”

This began a discussion about how “tied up” isn’t always used in a literal sense, like the singer had ropes wrapped around her or something, but is sometimes an expression for feeling constrained by something, like how when Mama had the twins and they had to stay in the neonatal intensive care unit for a while and couldn’t come straight home with us, Mama and Daddy decided not to go anywhere far away, because we would be leaving half our children behind. Mama and Daddy were “tied up” by the twins’ need to stay in the hospital.

And then this, from my 6-year-old: “We tie you up, don’t we, Mama?”

It took me a while to answer this question because, in a way, yes they do. Becoming a parent changes everything. It changes even the most seemingly simple things, like how late you can stay out playing a gig with your band because kids have to be in bed by 8 p.m. so they can concentrate well in school tomorrow, and how writing that has to be perfected in a quiet space can only be attempted during sleep time in a house filled with five wild boys, and how date night frequency is proportionate to how many people are willing to watch five boys alone (not many, I can tell you).

But these constraints don’t make us feel “tied up” unless we expect something different.

This has been a gradual knowing for me. When we had one child, maintaining our lives and all the extras and that relentless pursuit of dreams was still relatively easy. Even two children didn’t change a whole lot for us. And then we had three, and suddenly we couldn’t find shoes when it was time to go and clothes mountains (clean, just not put away) piled up on our banister and bedtime became a two-hour power struggle. And then, in the middle of that drowning, add two more to the count.

I like my control. I like my routine. I like to know that I will be able to write between these set hours and no one will disturb me because they’ll all be quietly sleeping in their rooms like little angels, but reality sends one child knocking on the door because he needs to go to the potty and he can’t reach the light switch and it’s too dark to move the stool to where the light switch is, and then another knocking because he feels a little bit scared all by himself, and another knocking because I forgot one book that he needs for his quiet time.

But even in this, my hands don’t become tied until I let them become tied by my sour attitude and my too-high expectations and my ridiculous dreams of an alternate reality.

These words from Laura Markham give me pause: “Our children learn values by observing what we do and drawing conclusions about what we think is important in life. Regardless of what we consciously teach our child, he’ll understand and shape his values based on what he sees us do.”[1]

I hope my children learn by my actions that my values tangle tight around family and relationships and nurture. I hope they know inherently that they do not tie me up so much as they set me free from irrational expectation and perceived disappointment and most of all myself.

Here is where peace settles for today: Understanding that parenting changes everything. Accepting what it requires and how much it takes.

And then giving without restraint so we are living without constraint.

This is an excerpt from Book 8 of the Family on Purpose series: We Live Peacefully. Hopefully. Courageously.

[1] Markham, Laura. Peaceful Parents, Happy Kids: How to Stop Yelling and Start Connecting. New York: Perigee Book, 2012.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

We live in a new day and age when it comes to publishing. We can publish at the click of a button now (well, as long as we do all the work beforehand). It’s really never been easier.

We no longer have to go through agents or editors at publishing houses or wait to hear whether our book idea has market potential, because we get to define that market in the first place.

In some ways, this is good. In others, it’s a little scary.

I recently shopped out a middle grade novel to six agents I specifically hand-picked, because I read that they were interested in a novel like mine. Four of them asked for the full manuscript. Two turned down representation because they didn’t have the right contacts for it but said they’d be surprised if I didn’t find representation.

I sent a full edited version to an agent at the beginning of June 2015, and I’m still waiting to hear her verdict: will she represent, or will she pass?

It’s been more than a year since the first query letter I sent. In that time I’ve almost finished six more middle grade novels (two for two different series and four for stand-alones), put together twelve books I decided to sell on my own and started work on two additional projects.

I say all this to say that the traditional publishing world is a world that takes time. Even after gaining representation for a project (which could take years), an agent then has to sell the manuscript to an interested editor at a publishing house. This could take a year. Then an editor may or may not (most likely yes) have suggestions for revisions, which could take another year or more.

After that, once it’s on a publishing schedule, it might take another year to go to print, because there are many other factors that go into print publishing, like book art, layout, and fine editing.

While all that is happening, the author is hoping that no other publishing houses come out with a similar novel that might make sales tank.

One might think this is all the more reason just to bypass traditional publishing and focus on self-publishing. And we certainly have more freedom in self-publishing. I’ve got an adult novel I’ve written in poetry that I’ve been pitching to different agents for eighteen months. No one will take it, even though they call the writing “beautiful”—because it’s a novel written in poetry. It’s different. It’s not standard best-seller material. Publishing is, after all, a business. I’m giving it another year before that one will be self-published.

But, still, it has always been my dream to publish something the traditional way.

Why? some might say.

Well, the answer isn’t really simple for me. I’ve always dreamed of my book on shelves. And the only way you’re going to get a book on the shelves of big-name bookstores like Barnes & Noble or the libraries across the nation is by going through a traditional publisher (or working way harder on marketing than I want to work).

I want my book in as many hands as can get it, because I believe in the story.

For me, this debate—to publish traditionally or to self-publish—is not really a debate at all. Mostly because I want to be a hybrid author. I want to publish some works in the traditional world and others in the self-publishing world. I want to grow my audience with authentic people who actually look forward to a new release from me, whether it’s a self-published release or a traditionally published release.

The point is that I’ll keep trying to gain representation for some and I’ll go straight to self-publishing for others. The traditional market is exactly that—traditional. It doesn’t often accept cutting-edge fiction or nonfiction, so when we’re writing work that falls into that category, it’s probably just better to save our efforts and time for publishing and marketing ourselves.

Writing and publishing is a business not just for agents and editors and publishing houses, but also for us, the writers, and the only way we can build a writing business is by constantly writing and constantly releasing. It’s hard to constantly release when the only method of release is a system that takes years to get through.

As writers who do the work, it’s smart to diversify.

Here are some questions I ask myself before considering traditional publishing or self-publishing.

1. Do I want this story to stay as-is, or would I be okay with some revision requests (sometimes very major ones)?

This is the question I asked when I received about 20 personal rejection letters (not the form ones) for my adult novel written in verse. Many said they’d take another look at it if I decided to take it out of poetry and add another 10,000 or so words. I thought about this for a while. Months. But I had another novel on deck, so, instead, I tried sending that one out.

When it was time to revisit the adult novel, I didn’t feel like changing it at all. So I added it to my list of potential self-published titles, sent it out to a few other people and now I wait for a while longer.

2. Is this a story that I feel could withstand the long waiting period of traditional publishing?

This is sometimes a more important question for nonfiction than it is for fiction. I considered sending out a project where I did a whole year of examining family values and wrote in a diary-like fashion. Really, what it amounts to is nearly 300 essays about the family values we examined for a year. But I didn’t think that story would be able to withstand the publication schedule, because who knows how long this “trend” of intentional parenting will last? So I’m in the process of releasing that one (nine books have been released, three more to go) on my own.

Some nonfiction will withstand the publication schedule because the projects are a little ahead of their time. This question helps sort out the waiting time for me. Most projects will keep, by the way. So then it comes down to: Do I want it to keep? That’s a question we’ll have to ask for ourselves.

3. Is this book a stand-alone, or could it be a series?

Some stories (like series) are much easier to sell as self-published authors. With series, there’s a natural lead-in to the other stories. But sometimes I don’t want to write series. Sometimes I just want to write a stand-alone novel (the middle grade one out with agents right now is a stand-alone).

Self-published authors have a much harder time selling their stand-alone novels, because they don’t exist in what’s called a funnel—a marketing term applied to creating a natural lead-in for more book sales (one book naturally leads to another). We can create funnels for them by thinking outside the box—giving away character profiles or deleted scenes—but I didn’t want to do that with this one. Because of that, I most likely wouldn’t be able generate great sales as a self-published author.

So I continue to wait.

For writers, this debate can get pretty complicated. Some say self-publishing is the only way. Some say traditional publishing is the only way. But I don’t think it has to be one or the other. There are definite advantages and disadvantages to both processes.

It’s worth it to ask ourselves which would be better—not for all our projects, but for one project at a time.

**Note: Before signing with an agent, be sure to have a conversation about the hybrid author plans. Make sure terms are laid out extensively and simply so there’s no confusion over which titles you’re creating for traditional publishing and which ones you’ll be producing yourself.

Week’s prompt

Write what comes to mind when you read the following quote:

“Imagination was given to man to compensate him for what he is not, and a sense of humor was provided to console him for what he is.”

—Oscar Wilde

by Rachel Toalson | General Blog

The other day I was trying to put my 3-year-old in the car, and we were in a hurry, because I wanted to get to the grocery store and back before it was time for their lunch, since you definitely DO NOT want to be caught out in public when two headstrong 3-year-olds and a 9-month-old decide they’re hungry and you’re not feeding them fast enough, because, look, we’re surrounded by food and all you have to do is BUY SOMETHING FOR THEM.

That’s a fight I didn’t want to have today. So I was doing my best to buckle the 3-year-old quickly and make sure the chest piece was positioned in the exact place it should be, because I’m all about safety, while he was more concerned with waving a book he’d found in my face.

“Look, Mama,” he kept saying over and over and over again. Wave, wave, wave.

“I’m trying to buckle you,” I said.

“But look what I found,” he said, still waving it in my face. I took the book and threw it down on the floor of the van.

“Stop putting the book in my face,” I said. “I don’t like it when you shove things in my face.”

He ignored me, of course, because he’s a 3-year-old and that’s what 3-year-olds do, and he replaced a book with his finger, which I know I just saw up his nose. It took a few impressive Matrix moves that I’m still feeling today to get out of that sticky spot, and then he was buckled and we were on our merry way, my annoyance dissipating with every mile we logged, replaced by anxiety and dread, because who in their right mind takes two 3-year-olds and a 9-month-old to a grocery store? I was totally setting myself up for failure, and I knew it.

But I distracted myself by thinking about how kids probably don’t even understand the whole concept of “I don’t like having things shoved in my face,” because they don’t realize they’re shoving a book in a face. They’re just trying to get our attention. It’s how they communicate.

I know, because I watched them after we got home from the store (which I don’t want to talk about, so don’t even ask). The two 3-year-olds were talking to each other, and one would hold a train right up into the face of the other one and say, “I want this one. Do you want this one?” Twin 1 was trying to pick a fight, but Twin 2 wasn’t taking the bait, mostly because he couldn’t see the train that was right up in his face. It was too close. So he just ignored it and said, “No,” and went right on playing.

There are so many things that kids don’t understand. Take, for instance, the “please don’t put your stinky feet on me.”

First of all, kids don’t even know what stinky smells like. They sort of know stinky when it comes to things like farts and skunk smell and food they don’t like, but when it comes to anything connected to their body, stinky is not a word in their vocabulary. They will come in from playing outside in the middle of a Texas summer and smell like a whole pasture full of cows and dung and the dog that was dispatched to round up all the strays that need milking, even though we don’t live anywhere near cows. They will fight to the death about taking a bath, no matter how many times we tell them that the smell they keep looking around trying to find is actually them.

Every night at dinner, the 9-year-old, without even thinking, will put his stinky feet that have been trapped inside his tennis shoes all day, on my legs. All over them, actually. He moves them up and down and side to side, because he has trouble sitting still after all that over-stimulation at school. I can practically see the fumes swirling up from his black socks with the neon green toes, and those fumes get to be rubbed all over my legs. Just what I wanted.

He does it because he’s not thinking and because he loves me, but THIS IS NOT LOVE. Trust me. It’s dinnertime, and all I can smell is Fritos mixed with pinto beans and really aged cheese, even though what we’re having is salmon with salad.

Kids also don’t understand things like “Please give me some personal space,” because what is personal space to kids? They will touch me and prod me and lean into me and not think twice about it. They will stand so close to me I’ll trip over them on my way to get some requested milk. They will fall all over each other and think it’s hilarious instead of annoying. They will cling to my legs on the walk to school, and then, when they’ve disappeared from my view because there’s a baby strapped to my frontside, they will stop, and my Matrix move skills will be tested once more as I try to stop myself from falling, and I’ll be sore for another month.

“I would like to go to bed” is probably the most misunderstood phrase in our house. To our kids, this means, “I would like you to come into our room a thousand times seeking extra hugs and kisses and to especially tell us in no less than 1,000 words what your brother just did to you.” Just when we’re falling into dreamland and it’s looking like the most beautiful place we’ve ever seen, someone will knock on our door with something important to tell us, like how he thinks that tomorrow is crazy sock day and he doesn’t have any crazy socks, so can he borrow some, and it will take us five more hours to get back to sleep.

“I would like to go to bed” is also code for “You can totally get out of your bed and take all the books down from the library shelves,” if you’re asking our 3-year-old twins, which is why we use a locking doorknob installed backwards on their room and lock them in it at night, because 3-year-olds roaming the house at night is scarier than that freaky doll Chucky coming for a visit with his eyes that never blink.

“Chew with your mouth closed” looks like a 3-year-old trying to figure out how in the world you’re supposed to chew food when you close your mouth, looking confusedly at all his brothers who have mastered the talent and then, after rolling the food around his mouth with his tongue, opting to swallow it whole so he chokes on a stump of unchewed broccoli.

“You’re not hungry; you’re just bored,” gets me tagged as the “worst mother ever.” And “That’s not in our budget right now” results in a boy fetching my wallet, pulling out a credit card and saying, “Then use this,” reminding me that I need to teach him about responsible use of credit cards, because society’s claws are thick.

So maybe things get a little lost in translation, but the truth is I’m kind of glad. Because it’s those times I feel really annoyed that a kid is waving something in my face and I’ve already asked him to stop once that I remember how these are all places where I get to consider things from their point of view and I get to remember what it was like to be a kid and I get to take a deep, long breath and hope I’m breathing in patience and not more boiling annoyance. And then I get to be a good mother who teaches and directs and walks them toward a deeper understanding of what it means to be human.

But, seriously, if you don’t get your stinky feet off me…

by Rachel Toalson | Books

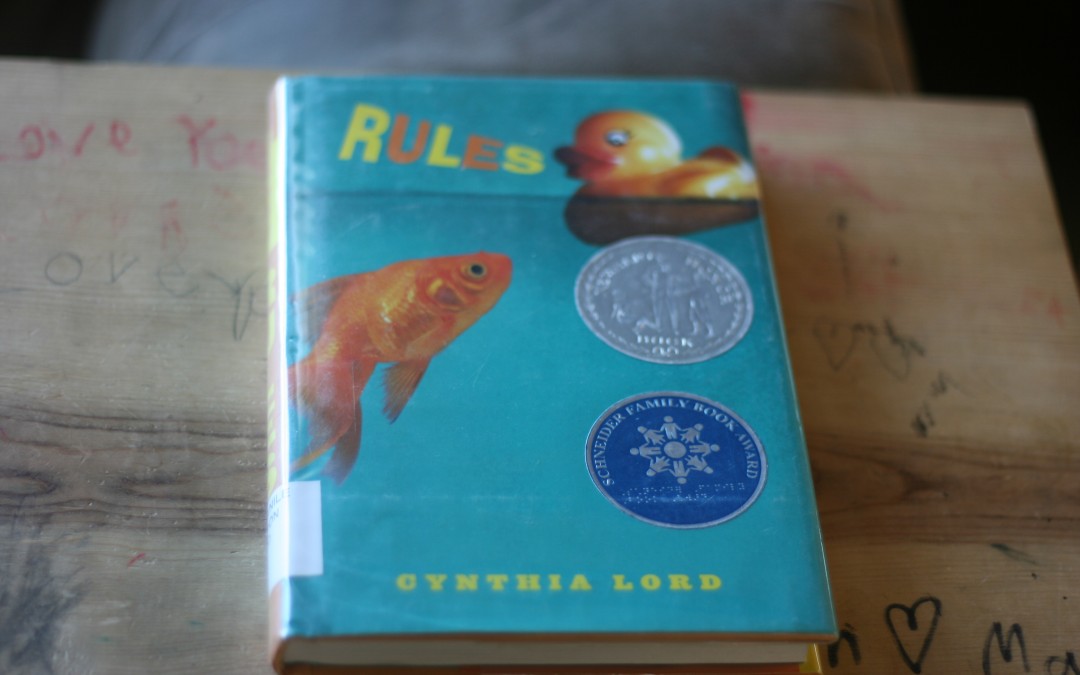

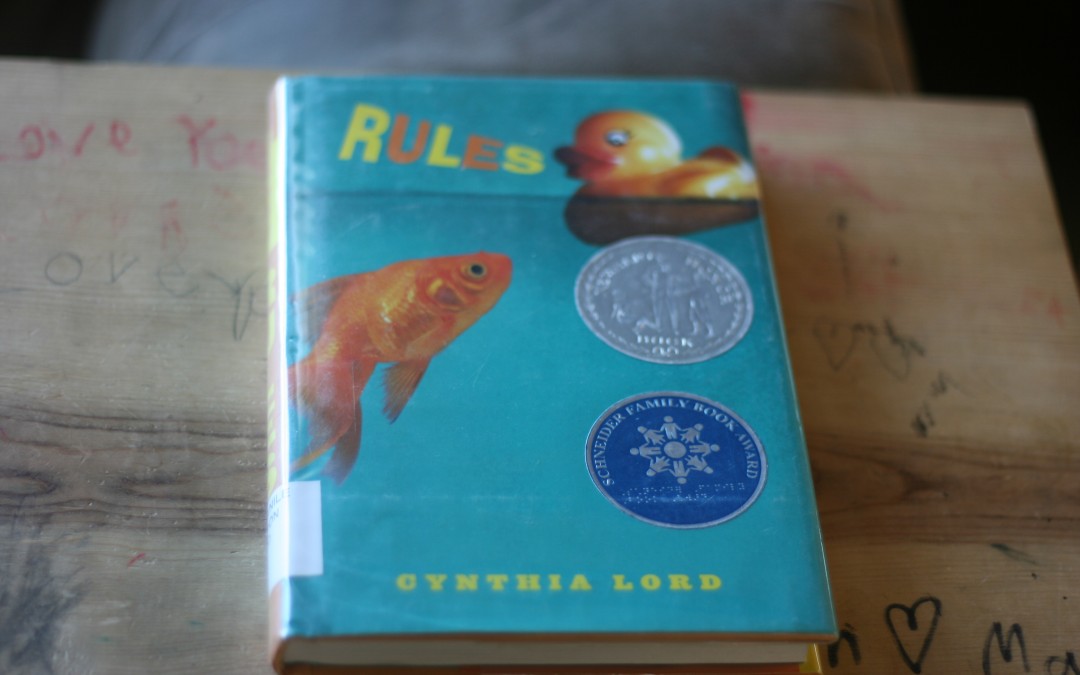

My favorite genre to read is middle grade fiction. If you’ve been around a while, that’s no surprise. My favorite middle grade fiction to read is the kind that burrows in your heart and doesn’t let go—and recently I read two books that won’t leave me be.

The first is one I read aloud to my boys during their lunch time read-aloud block. Rules, by Cynthia Lord, was named a Newbery Honor book in 2007. Twelve-year-old Catherine would like nothing more than to just be normal, but the problem is that she has an autistic brother who often makes that kind of life difficult. Not only do her parents have to pay much more attention to him (thus often sacrificing time with her), but sometimes he even embarrasses her in front of her friends—or potential friends. The other problem is that she really loves him.

A new girl moves in next door, and Catherine determines to be her friend, trying hard to hide her family’s abnormalities. Of course, abnormalities aren’t easily hidden. In the meantime, Catherine becomes friends with a paraplegic at her brother’s occupational therapy office by making him drawings for his communication cards, and she’s faced with her own standards of normal and abnormal. What’s so bad about being abnormal? Which would she rather be?

Rules was a beautiful story of love and acceptance and trying to work through the differences that often separate children but really don’t at all, because we’re all the same deep down. In multiple passages, as I was reading to my boys, I found myself getting choked up. Lord did a wonderful job of communicating the struggle of being the sibling or friend of a special needs kid.

What I loved most about Rules was not only that Catherine was an exceptionally compassionate big sister and friend, but she also kept a list of rules for her brother in the back of her art journal, hence the name of the book. They were social rules that are generally natural for most people, but not for kids like her brother David, who had autism. It proved her love for him.

Here’s a quote that shows you just how much Catherine loves her brother and how conflicted she feels about his autism:

“I look down between the raft boards and imagine my always-wish, my fingers reaching through the perfect top of David’s head, finding the broken places in his brain, turning knobs or flipping switches. All his autism wiped clean.

“But saying that wish brings trouble. ‘All people have a place,’ my third-grade teacher said firmly when I drew a pretend older brother in the “My Family” picture to be put out int he hallway for open house.

“I tried to tell her it was still David—but I wanted him to be able to play with me, and since I was fixing things, I made him older so he could stick up for me. But I had to draw the picture over and visit the guidance counselor instead of going to music.”

Just My Luck, by Cammie McGovern, was another book that featured an autistic brother, although the story wasn’t specifically about the relationship between the siblings. It was more of a subplot.

In Just My Luck, fourth grader Benny Barrows is not really in a great place. He’s trying to find a new best friend, he’s not really great at bike riding, even though his autistic brother is, and he also worries that his dad’s recent accident is his fault. While he’s trying to work through all the emotions and confusion of school—the girls are acting weird this year, he says—and how to handle an autistic brother and what to do about finding a true friend, his dad winds up back in the hospital, and Benny has to decide how far he’s willing to go—for both his family and himself—to carry on.

After reading Just My Luck earlier this summer, I added it to my two older boys’ reading lists. It’s a fantastic read full of humor, truth, inspiration and the art of perseverance. My 9-year-old read it in two days, because Benny, the main character, loves doing stop motion animation, and so does my son. I think he found a kindred spirit in Benny, and I love when books can provide that for my children.

What I liked most about Just My Luck was that it was a sweet story of a family. I loved the bonds between Benny and his brothers. He was the youngest of three, and while his older brother was a bit hands-off, as most boys in high school would be, he came into the picture when it really mattered. Benny’s middle other, George, was autistic, and it was heartwarming to see Benny relate to George at both school and at home.

Both of these books were lovely reads not only for middle grade readers but also for people like me, who prefer reading kid-lit over almost anything else.

I hope you enjoyed these book recommendations. Be sure to pick up your free books from my starter library and visit my recommendation page to see some of my best book recommendations. If you have any books you recently read that you think I’d enjoy, leave them in the comments and I’ll add them to my list.

*The books mentioned above have affiliate links attached to them, which means I’ll get a small kick-back if you click on them and purchase. But I only recommend books I enjoy reading myself. Actually, I don’t even talk about books I didn’t enjoy. I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them.

by Rachel Toalson | Messy Mondays

Kids are fun, aren’t they? I could think of a whole lot of other words to describe them, too. So dang cute, wonderful, charming, hilarious, imaginative, delusional, maddening, nasty, beastly, so dang annoying.

In the course of a day, there are a whole lot of things that make their way through my brain but, thankfully, remain trapped there in the crevices of a brain that has been dissected and digested by zombies children. Well, okay. They make it into my diary.

Here are some of my most private confessions. Don’t judge. I’m a stressed out mom. With a half-eaten brain.

1. When your kid says “I hate you,” and you want to say, yeah, well, I don’t really like you all that much right now, either.

(But you don’t, because kids are snowflakes, and you wouldn’t want to crush them.)

2. When your kid says he wants to run away and you want to say, “Here’s a sandwich. Make it last. Practice rationing.”

(But you don’t, because the neighbors would call CPS.)

3. When your kid says, “I don’t like that,” before he’s tasted dinner and you want to say, “Then you get a big bowl of nunya for dinner. And it’s delicious.”

(But you don’t, because you wouldn’t want to create an unhealthy relationship with food. Kids are so fragile nowadays.)

4. When your kid gets hit by his brother and you want to say, “Welp, you deserved that.”

(But you don’t, because kids need endless empathy to grow into healthy adults. Your brother hit you because you were yelling in his face, egging him on? I’m so sorry, baby.)

5. When your kid complains about doing chores and you want to say, “This is my payment for having you. Now get to work.”

(But you don’t, because child labor is not okay.)

6. When your kid says, “I threw up a little bit,” and you want to say, “Yeah, well, you’re out of sick days, kid. Suck it up.”

(But you don’t, because puke, everywhere. You don’t even have words anymore.)

7. When your 3-year-old argues with his brother for 15 minutes over whether or not the moon is a piece of the sun broken off, and you want to say, “What the hell does it matter?”

(But you don’t, because hell is a bad word. And 3-year-olds? Sponges.)

8. When your kid pushes that one button and you want to karate-kid his face.

(But you don’t, because, well, CPS.)

9. When your kid won’t stop copying you and you want to Duct tape his mouth shut.

(But you don’t, because you can’t find the tape you left in the drawer, which means someone probably already got to it and used it for sketchy purposes. You’ll find it when you try to lift the seat on your toilet. Ha ha. Very funny.)

10. When your kid asks, “Are we almost there?” before you’re even out of the neighborhood and you want to turn the car back around, park it in your driveway and say, “Yep. We are now.”

(But you don’t, because you’d rather have them all strapped in seats than running wild in the house.)

11. When your kid says you’re the worst parent ever and you want to say, “Ding, ding ding! We have a winner. Oh, wait. Nope, you’re not winning any awards for best kid in the world, either.”

(But you don’t, because self esteem. Snowflakes. Fragile. You don’t want to break them.)

(But seriously. Karate kid. And rationing. And suck it up. WORST. KID. EVER. right now.)