by Rachel Toalson | On My Shelf

On my shelf this week:

How to Make a Living as a Writer, by James Scott Bell

Isaac Assimov collection (fantasy)

Blogging for Writers: How Authors and Writers Build Successful Blogs, by Robin Houghton

Best quotes so far:

“Someone who knows how to think strategically, can calculate odds, and takes risks at the right time will win more often than the average player who depends mostly on the rolling bones.”

James Scott Bell

“Writing what you are passionate about is a good thing. But if you want to make a living at it you have to sell enough to bring in a profit. And that means objectively analyzing the marketplace.”

James Scott Bell

Read any of these? Tell us what you thought.

by Rachel Toalson | Stuff Crash Test Kids say

I like to show my muscles

(See picture above)

Asa (6): “I’m just wearing my vest, because you can see my muscles.”

Me: “…”

The ultimate laziness

Jadon (8): “They should make a bed with a toilet in it. Then I could go to sleep with no underwear on, and if I needed to pee in the middle of the night, I could just do it.”

Me: “…”

(He’s on the top bunk with a ceiling fan that could karate chop his head if he forgets about it. I’ll cut him some slack.)

No, I don’t want to ride a bike

Husband: “Okay! Who wants to ride their bikes out front?”

All the kids: “Not me!”

Me: “Oh, come on, guys. Don’t you want to practice riding your bikes?”

Asa (6): “NO! WE’RE SCOOTER RIDERS.”

Me: “…”

(He was genuinely upset, because scooter riders don’t mix with bike riders, apparently.)

A great simile or a weird one?

Boaz (3): “My throat feels like salad.”

Me: “…”

I not hungry

Boaz: “Mama, I hungry.”

Me: “Nice to meet you, hungry.”

Boaz: “NO! I NOT HUNGRY, I BOAZ!”

Me: “…”

Boaz: “I hungry.”

They’re like weapon magnets

(The twins are making noise on the back deck)

Husband: “I don’t even want to see what they’re playing with right now.”

Me: “Just look. Make sure it’s nothing bad.” (I’m feeding the baby. So it’s his responsibility.)

Husband: “Oh, dang. The recycling bin is on its side. They have old milk cartons. They’re using them to sword fight.”

Me: “That’s not too bad.”

Husband: “Wait. Those milk cartons were rinsed out, right? Because now they’re drinking whatever’s inside.”

Me: “…”

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life, This Writer Life Featured

I have a full manuscript out with a couple of agents. I’ve been waiting two months to hear from them, whether or not they want the manuscript or will pass so I can try submitting to someone else. I’m getting impatient. Every day I check some of the agents I follow on Twitter to see what kind of books they’re tweeting that they want to see, and every day I see something that sounds perfect for this book I’ve written. That’s out with agents. Sitting in limbo.

So then one of them tweeted about a literary middle grade novel written in verse—which is exactly what mine is—and I thought, this is too good a chance to pass up, because most agents don’t want to see novels in verse, and here was one calling for that exact submission. So I put all my submission materials together and sent it all flying across the Internet, mentioning that I’d seen his tweet and I hoped my manuscript was what he was looking for.

Not even 24 hours later, he emailed his rejection.

It knocked the breath out of me. It really did. Because he had tweeted what he wanted, and I thought I was giving him exactly that, because this novel is GREAT, and it’s interesting and it’s got the potential to change some lives in the literary sense.

And because my book was exactly the genre, exactly the format, exactly the description of what he wanted I let myself believe that his rejection meant that something was wrong with the writing mechanics. Maybe I hadn’t done as good a job as I thought communicating and crafting my story. Maybe the writing fell flat. Maybe it was really terrible, and here I was thinking it had a chance.

Except I know that none of that is true. I know it, because in seven query letters sent out, I’ve had four full manuscript requests, which has NEVER happened with any of my other stories. I know the writing is good. I know the story is great. I know the main character is lovable and quirky and mysterious and everything a lead character should be. So why did this guy pass on it so quickly?

Well, there are a lot of answers to that.

Rejection is hard. So many times we can take it so personally. Agents say “it’s just not right for my list right now,” and what we hear is, “You’re just not a good enough writer for my list.” Agents say “I don’t believe this is a good fit,” and we hear, “I don’t believe you’re a good fit.” Agents say “I’m going to have to pass,” and we hear, “It’s not any good.”

But what I’ve learned more surely from this experience is that some people will love what we write and some just won’t. There’s nothing we can do about that. If we try to please them all, we’d never have a book.

All rejection really means is that our project is not right for that one person. It doesn’t mean (necessarily) that it will never be right for anyone, ever. It doesn’t mean that we will never get traction with the project we poured ourselves into for an entire year. It doesn’t mean we have written for nothing.

Many factors influence whether or not an agent accepts a project or passes on it. Sometimes they have a similar project already in the queue, and they know it would be hard to sell two of them back-to-back. Sometimes they don’t connect well with the story, for personal reasons. Sometimes they’re looking for a very specific kind of book and yours just happens to be off by one tiny little detail.

Sometimes they don’t have the contacts that would sell your novel in the most efficient way, and even though they recognize it’s good, they’ll pass because they want you to get the best sale. Agents understand that at the heart of a publishing career is a good connection between an agent, a writer and a publishing house. If they think they can’t sell the project in a way that’s most beneficial to the writer (which will most benefit them, too), they’ll pass.

These are all the things you don’t see in a rejection letter, because agents are busy and inundated with submissions every hour of every day. There’s no way to know who would be a perfect fit and who wouldn’t without trying.

We at least have to try. That’s what I did, and even though I got an almost immediate rejection and sat in a tailspin for a couple of hours, unable to even write, eventually I lifted my head and got back to work.

Rejection will not stop me. It shouldn’t stop any of us. We are writers, first and foremost. Of course we will keep writing.

So let’s pick ourselves back up. Let’s brush off the dirt that got on our knees. Let’s keep writing.

Here’s how to see rejection for what it’s worth:

1. Remember that you are not your work.

We can become so tied to our work that it begins to feel like it’s a vital part of us. We will never have an objective viewpoint if our work is part of us. So we have to separate ourselves from it and send it out into the world without any expectation for how it will be received. Easier said than done, I know.

It’s a precarious balance when we’re writers, because the writing that holds more of us will always be better, and yet we still have to fight for this separation so we don’t take rejection too personally and close up shop forever. We should always try again.

2. Listen to the rejections.

If all the agents who send you a rejection include a note about something similar in your story that made them stop reading or showed them the project wasn’t right for them, listen. Chances are, even if you choose to self-publish that particular book, your readers will probably feel the same (because agents are, at their simplest, just readers).

That doesn’t mean we should listen to all the words in a rejection letter. Most of the rejections for my adult literary novel had to do with it being a novel in verse. If I took it out of verse, they could sell it better, they said. They didn’t have the right contacts for it, but it was beautiful writing. The story was fantastic, but they would need prose, not verse.

I decided to self-publish, because I don’t like the idea of someone telling me no one wants to read an adult novel in verse. I like proving people wrong. But mostly because taking the novel out of verse would change it in ways that wouldn’t suit it, in my opinion. (This project hasn’t published yet, by the way. I’m sitting on it for a while.)

3. Keep all your rejections, but don’t dwell on them.

Sometimes agents might include a little caveat like, “If you ever have anything else to submit, let me know and I’d love to take a look at it.” Phrases like these are golden, because they mean the agent really liked your writing, but the project simply wasn’t right for them. So keep all those rejections for the next time you have a project you’d like to submit, and you already have a much more targeted list.

4. Go have a glass of wine.

Celebrate that you were brave enough to try.

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test featured, Crash Test Parents, General Blog

A few weeks ago I got a text from my sister, who had her third baby in February. The text said, “Tell me you have days when you just can’t handle it. When walking out of the house is all you can do to survive. I just need to hear it from another human.”

I laughed out loud, even though I knew she was dead serious. And in my head were responses like “every damn day” and “just this morning” and “on a minute-by-minute basis.”

Parenting is hard. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I used to run six miles every morning in 10,000-pound humidity before commuting an hour to downtown’s Houston Chronicle office. I used to marathon-train on 10 miles of hills pushing a double baby stroller that carried a 4-year-old and a 3-year-old. I used to work for a narcissist.

Parenting is still the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

There are so many hours of my day that I just feel like giving up and hitch-hiking to downtown San Antonio’s Riverwalk, where Husband and I had a life before children—a life that didn’t include a panic attack every time a kid steps too close to the edge of the path and I imagine having to jump into that dirty black water to save him.

Like the morning last week, when the 3-year-old twins went outside into our very safe (normally) backyard while I transferred a load of laundry from the washing machine to the dryer. Two minutes, tops. That’s all it took. By the time I finished, one of the twins had come back inside, and the whole house smelled like gasoline.

“Why does the house smell like gasoline?” I said, to no one in particular. The twin looked at me. I looked at him. He had his guilty eyes on.

“What were you doing out there?” I said.

“Nuffing,” he said.

I knew it was definitely something, because of those guilty eyes. A mom always knows, after all.

His twin brother came in smelling like a gas pump, so I looked out on the deck, where they didn’t even have the foresight to hide what they’d been doing. There, on a deck chair, was their daddy’s gas can used to fill up the lawn mower the three times a year he mows. That gas can is stored behind a locked door. A locked and sealed door that somehow, SOMEHOW, these Dennis the Menaces had cracked open in less than two minutes.

They poured gasoline (less than half a gallon, for those who are concerned) all over the back deck, the grass and themselves. It’s a good thing no one in my house smokes, because we all would have been blown to high heaven.

I put them both in the bath (which was not on the schedule for the morning) while the baby stayed downstairs in his jumper seat wailing because he doesn’t like to be alone, and washed them, rinsed them, scrubbed them, rinsed them and washed them again. Husband sprayed off the deck (which also wasn’t on the schedule for the morning) and saturated all the grass, because a Texas summer hits 4,000 degrees, and we were afraid the sun might make the gasoline-drenched grass spontaneously combust and blow us all to high heaven anyway.

That morning was one of those give-up days, because there’s no way to be one step ahead in my house. There’s no way I can fully toddler-proof every room. There’s no way I can keep them out of every single thing they find to amuse themselves. It would take 23 of me.

That morning I wanted to walk out and let them fend for themselves in gasoline scented clothes that spread their stench all over the house in less than two seconds.

I used to feel guilty when feelings like this crept up. I used to beat myself up for sometimes wishing that they just weren’t twins, that there weren’t two of them ALL THE DANG TIME, that they weren’t so insatiably curious and 3 years old and nearly impossible to parent right now.

But there is something important I’ve learned in my years of parenting: Just because there are moments when we want to run away, when we want to flat-out give up, when we want to trade our kids for easier kids for just this little moment in time so we can catch up and learn to appreciate them again, it doesn’t mean that we don’t still love them with a love that is never-ending.

These little, irrational humans can be the best and worst people we know on any given day at any given moment.

There are days when I want to sit down and color next to my 3-year-olds, because they’ve just been playing so well together and the morning’s disasters have been minimal, and, gosh, I just love them so much, and then there are mornings when I want to put them on Craig’s list’s free page (I’d have to lie to really sell the idea, though. Something like “Two well behaved twins, of undetermined age.” Because what kind of crazy person would want two 3-year-olds voluntarily?)

There are hours when I love to comb through those old picture albums that show these two hooked up to machines because they were premature and remember how I fretted and cried and tried my best to help them learn how to eat, and there are days when those first moments feel like entire lifetimes apart from this moment, when they stuck their whole arm in the just-used toilet to see what poop floating in pee feels like (They already know. We’ve done this drill before.).

There are minutes when I pull them into my lap and kiss all over their faces until they’re giggling uncontrollably, because they’re getting so big and so fun, and then there are minutes when I’m half-heartedly holding their big brother away from them so he doesn’t clobber them for marking all over his journal with a giant red permanent marker they found lying around somewhere (who keeps giving us permanent markers? Please stop.).

Parenting is not for the weak. This is the hardest responsibility we will ever have in our lives. Raising another human being to be a decent person is not easy, and there are many times along our journeys when we will feel like giving up and giving in and giving out.

It just comes with the territory.

So I fire off my response to my sweet sister. “Yes,” I say. “Just about every day. Doesn’t mean you’re a bad mother.”

Because it doesn’t.

These moments when we feel the tension between wanting to give up and knowing we can’t make us stronger parents. They make us better people. They drag us into a deeper understanding of love.

Good thing, too. Because my toddler just figured out how to open a can of paint Husband left unguarded and now the pantry wall has a Thermal Spring scribble-masterpiece drying on it.

I’m going to be one amazing person by the time this is all over.

by Rachel Toalson | Messy Mondays

Want to know how I can surely tell that school has started?

Well, of course there’s the amazingly quieter house. That’s a given. But that could just be older boys who are playing on their scooters out front and twins who are locked out back and a baby who’s just as sweet as can be.

There’s also the refrigerator that actually stays closed for an hour at a time, but that could just be kids away for the weekend (any takers?).

No, the biggest clue that school has started in my house is the stack of papers sitting on my bed.

Those are the look-at-later papers.

All three of the boys in school came home with 400 pieces of paper in their red and blue folders (It wasn’t really that bad. It was only 398 papers.) on the first day of school. I had to wade through all of them, because some required further action, like a signature or some kind of permission or even more school supplies. Some of them just went into this pile, to be looked at later (or never, which is much more likely).

We started the school year sprinting. We were so organized I was impressed with us. Everybody picked out their clothes the night before, the backpacks were all hung ready to go, and even the school lunches were packed in the fridge. And then the first day happened and all.these.papers. Is it really necessary to send 5,000 school lunch menus when our kids don’t ever eat school lunches? Is it necessary to send three copies of the same exact information sheet? Is there a place where I can opt out of papers?

Because I know exactly what’s going to happen. It happens every year. We will start off great. I will come down to dinner every evening and sort through those papers in five minutes or less, placing some in a recycling pile, some in a look-at-later pile, some back in the folders because they need returning.

And then I will forget I ever had a look-at-later pile, and by Christmas there will be so many papers we could have saved sixteen trees.

I mean, if this is the price I have to pay to have a little peace from an 8-year-old whose daily grand ideas include starting a vegetable garden in our front yard (cucumbers and carrots are starting to grow in the rose garden) and selling water art paintings out by the mailbox where I can’t even see him, a 6-year-old who’s always hungry and will eat a 2-pound bag of apples if I’m not paying attention, and a 5-year-old who likes to snack on Tom’s toothpaste, then I guess I’ll take it.

Just don’t ask me if I saw the list of school supplies they need for GT. It’s buried somewhere in my look-at-later pile, so. Cut me some slack.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I see you all the time. You probably think I don’t notice you, because no one else in the world does. But I do. I see you on the fringes of the schoolyard, just after school’s let out and you’re hoping no one will notice you don’t have any friends waving at you for the see-you-tomorrow. I see you walking alone down the neighborhood sidewalk while those others are laughing ahead of you, the way you turn to look behind you and drop your head when you meet a person’s eyes because those ones who should be friends aren’t waiting up or inviting you to share the sidewalk with them. I see you standing at the bus stop, fidgeting on your feet while the teens in front of you snap their gum and talk about what they did last night.

But mostly I see you online. Mostly I see you commenting on threads, adding little or no value but only finger filth, lining up your figurative shotgun and pulling the trigger because it makes you feel better to get it all out there like that. They wouldn’t like you, anyway, if you tried to be someone other than this.

Mostly I feel the wound your words turn red.

And for a while I felt angry about you and your shots. I felt angry that a girl could put herself out there on the Internet, this place with so much potential to build community between different cultures and age groups and genders, only to be ripped down to the floor and gifted a black eye or a swollen mouth or just a bruise on the gut no one can see. At first I wanted to lash right back out and hurt where you had hurt and punch where you’d pouched and knock asunder like you’d knocked asunder.

And then I remembered something I’ve learned in my life so far, mostly because I’m a wife and a mother and a friend and a sister and a daughter.

We hurt when we are most hurting. We need love when we are most unlovable. We need kind people when we are most unlike a kind person.

There is something mysteriously powerful that happens when kindness meets cruelty, you see. I’ve seen it in my marriage. Those moments when I most want to strangle a dream in a man’s heart or throw out those words we sorted through last time or become the ugly person I feel balled up inside, those moments when I’m just so angry the heat of my head might burn the whole house down, and I would gladly watch the purge, those moments when hate meets love, are some of the most life-changing moments I’ve ever experienced. If I’ve failed and become that ugly person I really don’t, at the heart of me, want to be, and my husband meets that person with open arms and an understanding heart and overwhelming love, all those walls come crashing down.

So I started looking at your profiles. Not in a stalkerish way, but in an I’m-really-interested-in-knowing-you way. And do you know what I found? You are different, but you are all the same.

Not despicable, just passed over. Not overtly cruel, just doing what you know best to do. Not trying to be hated. Wanting to be loved.

Some of you didn’t grow up in homes with a mom like I try to be to my boys, and so you come out in droves when I’ve written something celebrating mothers, because you want to make sure I know there are a whole lot of sh*tty mothers out there. And I know this. There are. I didn’t have one, thank God, but I’ve walked with friends and family through the healing of their own traumatic childhoods with their mothers. And fathers.

Some of you don’t understand the beauty of true relationships, and so when I write about my big family, you come out to tell me that maybe I should have had an abortion or two or six, rather than populate this planet with more awful humans, and I’m so sorry that you’ve had such a hard time finding what we are all meant to find in community and friendship and love.

Some of you just don’t know what else to say or how else to say it, because you never had a model of good communication in your life and, in fact, only had someone berating you and criticizing you and making you feel like less than a person at every turn, and do I possibly know what that feels like? Could I possibly know how hard it is to recover from trauma like that? Could I excuse you for trying?

You come from different places, but you are all the same. So I want you to know the freedom I have uncovered in my life so far: There is somewhere you belong.

But the thing about belonging is you have to accept it. You have to believe it. You have to know it’s yours. And if you don’t, there are no words in the world a person can repeat often enough in just the right tone that will make any difference at all. You will never feel like you belong completely until you accept that gift.

It’s not easy to accept our belonging. I know. It’s scary to get involved in relationships, to open up enough to let people see the real us, all the way down to the deep parts we would rather hide away because maybe they won’t like us anymore if we open that door, the one where child abuse hides or where an unplanned pregnancy hides or where alcohol addiction hides or where homosexuality hides.

Belonging is a fundamental need. We need it as children, and some of us, tragically, don’t find it then. We need it as teens, and sometimes that’s the season when it’s most elusive. We still need it when we’re all the way grown.

I know how lonely it gets on the fringes. I used to keep myself there, because I was hurt badly by some important people in my life, and I just didn’t know if I could trust any of the other important people in my life. Because of the shield I wrapped around myself, I never really felt like I belonged anywhere. And because I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere, I didn’t let love penetrate my heart the way it’s supposed to. I didn’t let it beat my heart tender. I didn’t let it soften the hard.

I hurt people in that strong, stoic, unaffected place. I hurt them with words and looks and ill-aimed shots of my own. So we are not so very different, you see.

Every shot we take is just a cry for help. Help me become better. Help me know love. Help me belong.

When I see you now, bleeding on the Internet, hiding behind your anonymous comments, more often than not, I stop and I think and I observe. Most of all I see. I see you. I see your value. I see what you could be, if you let belonging crush that metal shield you’ve put on.

So please. Open wide. Let us see you. We won’t laugh or point or run away. We will show you that you belong.

We don’t have to be like anyone else to belong. We just have to be ourselves.

Just be you. And let us show you just what love can do.

by Rachel Toalson | On My Shelf

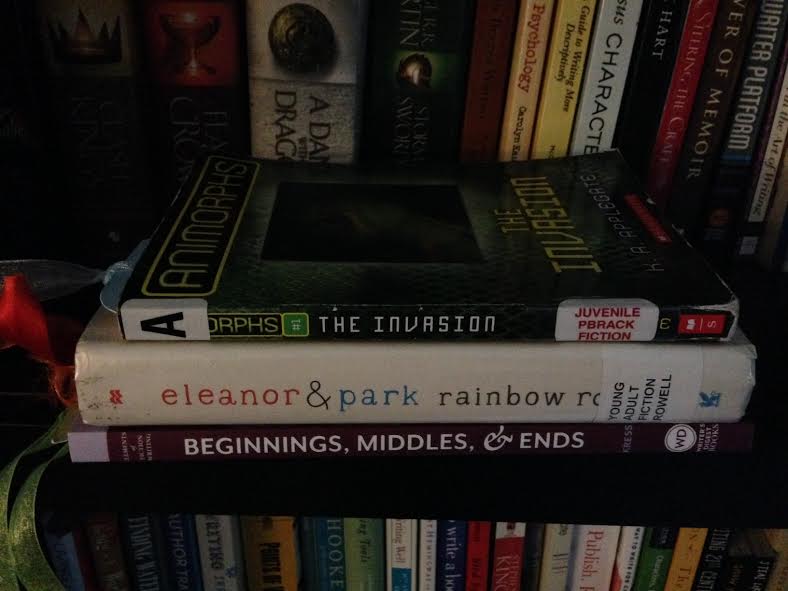

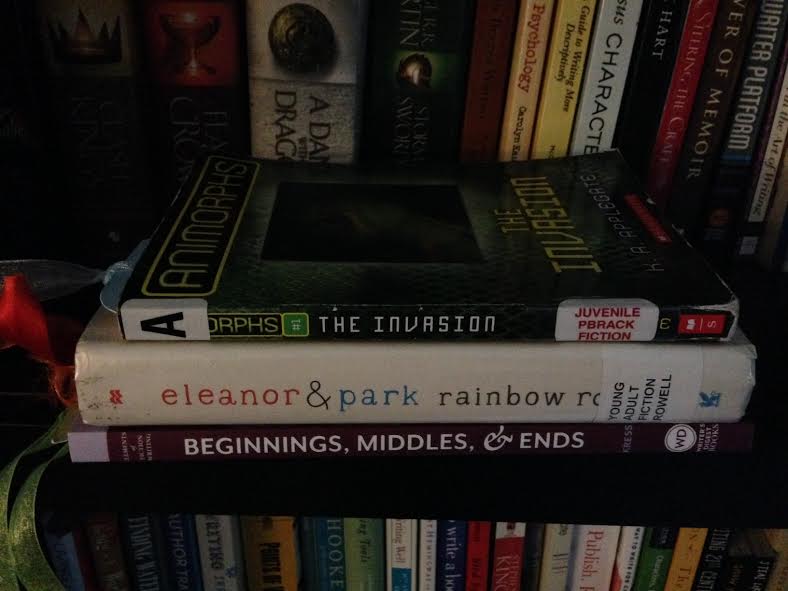

On my shelf this week:

The Invasion, by K.A. Applegate

Eleanor & Park, by Rainbow Rowell

Beginnings, Middles & Ends, by Nancy Kress

Best quotes so far:

“Eleanor was right. She never looked nice. She looked like art, and art wasn’t supposed to look nice; it was supposed to make you feel something.”

Rainbow Rowell

“He made her feel like more than the sum of her parts.”

Rainbow Rowell

“The first time he’d held her hand, it felt so good that it crowded out all the bad things. It felt better than anything had ever hurt.”

Rainbow Rowell

Read any of these? Tell us what you thought.

by Rachel Toalson | Fiction in Forty

Photo by Abigail Keenan.

What was she doing out there on the open road, riding straight down the middle? She had three kids at home, waiting on her wake-up call. A husband waiting for an early-morning chat.

Now they will keep waiting.

by Rachel Toalson | My Good Journey

It’s been a rainy summer, which means kids have been cooped up inside the house (because mud. And boys.), and everyone is touching me, and what I would give, what I would give for some cable television to distract them.

We got rid of cable years ago, back when the oldest was 3 and we decided we didn’t really want to afford the expense because it really wasn’t worth it.

Fast forward five years and four additional kids, and now here we are, nearing the end of the kids’ summer break, and my boys are fighting constantly, and so much work needed doing but didn’t get done because it’s summertime, and so many days, honestly, I just want to sit them down in front of the television and turn on a movie just to get an hour and a half of peace and quiet, bought with a single flick of the Apple remote.

A mom can only take so much, after all.

Except I know our values, and television, the passive participation in family life, isn’t one of them. Drawing or writing stories or reading books or building amazing contraptions from blocks or painting masterpieces or running wild outside—those all fit in with our values, but they’re so much harder.

So much harder on the days I’m already exhausted.

But the truth is, I want my boys to engage their minds and bodies in ways that can’t be done in front of a screen, even if we’re “sharing” the screen time together by watching a movie.

It’s not really shared time for me, because even if I sit down on the couch with them, I know what I’ll do. I’ll engage in other work. I’ll find something else to do besides staring at a screen. I’ll write or read or brainstorm or stare at the baby or think about how I should be washing the dishes.

So it’s not shared activity like building a LEGO tower or coloring a page out of a Spider-Man coloring book or painting an interpretation of The Starry Night.

I grew up with a television and the lure of a screen, but it is nothing compared to the temptation my children face every day in the way of screens.

Our generation of parents is growing up with screens everywhere–iPhones and iPads and iMacs and Apple TV and Internet and social media. So many opportunities for kids to get lost in screens.

These screens can hijack family life in relentless ways.

Especially for parents. People need to get in touch with us, so we keep our phones on and our email (on the phone) open and our social media channels (on the phone) perpetually logged in, just in case.

We are connected all the time.

Sometimes I get tired of this connectivity. Because it’s not real. Because it’s across a screen. Because I know what it can do to real connectivity.

Back when we were deciding our family values, we talked extensively about how it’s so difficult to listen earnestly to our children when we are constantly connected to our screens.

We miss the important things—the way their eyes shine when they read the last page of that chapter book—the first one they’ve read on their own. We miss the funny little dance he did on his way to the potty, the one we might have remembered to show him years later, if we’d seen it.

We miss life.

The first step to walking in greater connectivity with our children is disconnecting in the ways that will foster more authentic connection—and being an example for them.

So that’s what I choose to do, from here on out. I’ll put down my phone. I’ll log out of all those accounts that seem so important and urgent. I’ll keep the television hidden so its “easy” promise won’t start calling.

I’ll look at them and be with them and engage fully in their minutes and hours and days.

The life unfolding before my eyes is worth seeing.

Ways to connect besides screens:

1. Read an audio book together. This is such a special, shared experience for a parent and child. There are some amazing audio books at local libraries that rival theatrical productions. My boys will sit, riveted, for hours when we find a good one (and we recheck it as often as we can—because moms need a break, after all!). Some of our favorites: Peter Pan, read by Jim Dale. Hatchet, read by Peter Coyote. There’s a Boy in the Girl’s Bathroom, read by Lionel Wilson. The Harry Potter series, read by Jim Dale.

2. Write a picture book together. We are doing this with the 8-year-old, 6-year-old and 5-year-old the real way—publishing it on Amazon and everything. But, on a much smaller scale: Get 18 sheets of computer paper and fold them in half. Help your child write a story on the pages and then let him/her draw all the pictures that go inside.

3. Have a dance party. Turn the tunes up high and get down. This promises plenty of giggles and fun. Kids love to dance, and it’s good for their bodies to get moving. My boys love to dance, and there’s nothing more effective for cutting tension in two (at least not in our house) than breaking into a silly dance.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Is it better to self-publish or traditionally publish? Well, the answer is both. But it depends on the project.

Here’s a guide for the pros and cons of publishing, as far as what I know today.

1. The book release.

In traditional publishing, someone else takes care of the book release. With self-publishing, it’s all up to us.

This is a big one, for me. Right now I’ve released three books, and each of them probably took a total of about 15 additional hours to complete, beyond the writing part. Those hours were spent on things like fine-editing, laying out the books on a page (because they included pictures), getting them uploaded in all markets (which I’m still working on). If we’re not great with the technical side of the equation (I’m not!), self-publishing can seem daunting.

It’s not easy learning all that needs to be learned in order to self-publish. It’s also not quick. It’s an investment of our time, in our business. Our first few releases will take much longer than the ones that come later, because the learning curve is pretty high. But once we learn it, publishing will get much easier.

Of course, with traditional publishing, we don’t have to worry about learning any aspects of publishing, because someone else does it for us.

2. Book elements.

With self-publishing, we have more control over all the elements of our book. This would be anything from the revision process to the way the cover looks. In traditional publishing, we don’t get to pick things like who we want to design the front cover of our book. I can’t go to an agent or an editor and say, “Hey, my husband designs book covers, and I’d really like him to design this one.” Nope. They have their own people in mind.

But I can do that when I’m in charge of all aspects of book publishing.

Now, the downside to this is that if something is off—if the cover isn’t perfect but we think it looks great (because we don’t really have much expertise in design), we won’t know except by sales that just aren’t there. If there’s a typo in our book, it’s up to us. It’s not up to an editor at a publishing house.

That can feel like a lot of pressure.

When I was about to publish my books, I had a really hard time releasing them. I sat on them for weeks, because it was just so scary to release something on my own, without the benefit of having lots of eyes (agents, editors, book designers) who may have found a glaring mistake that I missed after looking it over a hundred times. Unfortunately, readers are not as forgiving when it comes to book errors if you’re a self-published author. They’re much more forgiving if you’re a traditionally published author, because they know it’s probably not your fault.

So if you’re going to self publish, the manuscript should be as close to perfect as it’s ever going to get.

3. The revision process.

In self-publishing, we have full control over the revision process. This can be a good thing. Who wants to spend years and years on a book, only to hear that someone thinks it would sell better if we took it out of first-person point of view? On the other hand, what if that information is correct, and we don’t have someone telling us?

As self-publishers, we have much more control over the revision process of our manuscript, but we also lose that contact with other people who really do know what they’re talking about. A middle grade novel I wrote is currently in the revision process with an agent, because she noticed something that could have added depth to the book. And she was right. I’m so glad she pointed it out. If I were just self-publishing the book, I might have missed adding that layer of significant meaning to my book.

And every time I get a revision request for a manuscript, I learn something new that I can apply to my self-published titles as well (which is why I enjoy being a hybrid author).

4. Marketing.

Unfortunately, there’s not much difference here between self-publishing and traditional publishing. Publishers no longer take care of advertising and marketing for their published authors, so you’re on the hook for building your own platform, either way.

5. Distribution.

Book sellers (the non-virtual kind) will not acquire your book unless you’re published through a traditional publisher. If you’re self-published, you can get those titles online as ebooks (and also pay to have them sent to people who might want to have a hard copy—but your margin of profit is much smaller on those), but you will never see them on the shelves of a book store or in a library. Even a self-published ebook that does well will not be offered in a library’s database until it’s been traditionally published.

Some people think that bookstores will be gone in the future, and we’ll just be buying books online, so maybe this doesn’t even matter. I like to think bookstores will be sticking around, and I want to have at least a few of my books on their shelves. So I’ll keep trying for traditional publishing.

6. The representation process.

This process can take a really long time. Years for some projects. Sometimes this is enough of a negative in itself. To research agents who might like my book, and produce a query letter and ready the manuscript for submission and write a synopsis probably took about 20 hours start to finish. I’m not guaranteed a return for those hours like I am if I just self-publish. And then it’s a waiting game from there. I’ve been sitting on my middle grade novel since January, still waiting to hear if two different agents want it.

7. The feeling of accomplishment.

I’d say this is the same for both. While it’s really encouraging to have someone interested in your book, to let you now that it’s not just you who thinks it’s pretty awesome, it’s also very satisfying to see your book in print and know that you did it ALL. So, either way, it’s a win.

8. Let’s not forget money.

As a self-published author, I get to keep much more of my profit (when I’m not giving books away for free). I can also give book away for free, if I choose to. In traditional publishing, you’ll get an advance (a sum of money that will “pay” for the writing of your book—usually not much if you’re a first-time author). After that advance, you won’t get any money until the publishing house recoups the publishing and distribution costs. So it could be a long time before you see any money from that. And even if you start making sales money again, the publishing house takes a cut, and so does your agent.

Of course you don’t get to keep all the money from self-publishing either—about 70 percent of the price of your book, because places like Amazon and Barnes & Noble have to pay to have your books displayed and included in search engines. But what you make, percentage-wise, is much more than you’d make publishing traditionally (only about 3-5 percent).

Now it’s up to you to decide: self-publish or traditionally publish?