by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

This whole afternoon, since getting home from school, he’s been quiet and withdrawn, and I know him well enough to know that there is something weighing heavily on his 8-year-old heart.

So even though I should be working and he’s caught me in the middle of a story, I set my laptop on the coffee table and turn my full attention to him.

“What’s bothering you, baby?” I say.

Sometimes he talks and sometimes he doesn’t, so I’m not entirely prepared for when he says, “Some kids were mean to me at school today.”

And the first thing I want to know is who, because being mean to my boy is not tolerated in my mama heart.

It takes great effort to ask the question that won’t answer this one.

“Oh, yeah?” I say. “What happened?”

He was playing on the playground today, he says, and he asked his friends if they might want to play a Power Buddies game he’d made up.

Power Buddies are characters my boy has been developing for a year now, superheroes with elemental super powers. He has created a whole new world where they exist and loves to share that imaginary world with his friends. Often, they play along willingly.

“They said Power Buddies were stupid,” he says, and his voice breaks clear down the middle. “They said I would never write their stories and publish them in a book. And even if I did, no one would read them.”

He’s crying hard now because of this hurt. Blood starts roaring in my ears.

Because I have been here before, too.

But I don’t try to fix it. I don’t try to make him feel better. I just fold my boy in my arms and let him cry at this hurt from friends he thought loved him the way he loves them.

There will be time for what comes next.

///

My second year of college I signed up for an introductory creative writing class.

The first day of class I knew I wouldn’t like my professor. He was arrogant and opinionated and rigid in his beliefs about the way things should be done.

The first poem I turned in was a religious one about how dark and light can coexist. It wasn’t very good, but it wasn’t bad enough to merit the big red C he marked on it. He’d scrawled a piece of explanation across the back page. “Leave religion out of class,” it said.

So I did. And yet every poem I turned in after that he marked “melodramatic” or “flowery” or “fluff,” no matter how happy or dark or serious I got.

He used my short stories as material to rip apart in class, in front of the 25 others students.

He was a bully through and through, set on discounting me at every turn. But I didn’t drop the class, because I was not a quitter.

I stuck around and kept trying, kept getting better, but he never could bring himself to acknowledge that I was the hardest worker in the class.

When he handed back my last short story of the semester, it was with the words, “You will never be published. Look for something else to do. Your writing is not good enough.”

The words dropped down deep and sat there like permanent stones.

///

If we’re not careful, the words that others speak so carelessly can become more than just words. They can become lies that we believe.

I let those words of my first creative writing professor derail me for a while. I let them tell me what I could and could not do. I let them still my pen, because, of course, he was right.

What was the point?

For six years, every time I tried to pick up a pen, his voice came whispering from that dark wound in my heart.

No one cares about this story, he said.

These characters are boring, he said.

You will never, he said.

And then, one day, I decided to test that lie. I decided to open my notebook. I decided to write.

The thing about those critical voices is that when we test them and find them as untrue as they actually are, they then have the potential to launch us into greater determination and effort.

I let the words wreck me for a time. I gave up, but my giving up didn’t make me feel any better. I knew what I was made to do, and letting someone else determine whether or not I did it left me hollow and shaky on the inside.

So I chose to write—not to prove him wrong but to prove to myself that I could do it when someone said I couldn’t.

Sometimes those voices aren’t curses at all. Sometimes they are the greatest blessings of all.

Because in overcoming them, we learn just how resilient we are.

///

Two years ago I sat in the lobby of a hospital with my husband for a meeting with the pastor of a large church where my husband was spending a few months as the interim worship pastor.

The pastor had called a meeting to tell us that if we were to move forward, if my husband was to get the worship pastor job, I would have to stop leading worship with him.

My voice just wasn’t good enough for the size church he led, he said.

I was playing in the big leagues now, and I didn’t have what it takes, he said.

There would be no husband-and-wife music ministry at his church, he said.

I sat and listened to his words, and I would not let the crumbling inside make me cry. I didn’t say a single word about his thoughts, just thanked him for his time and walked back to the car with my husband when the torturous time had finished.

I spent a whole year reeling. My husband and I found somewhere else to serve, where people made it their mission to seek us out after the service ended and tell us how much they enjoyed our voices together. They couldn’t see it from where they sat, but every single time I got up to the microphone to sing—every single time—I heard that pastor’s voice.

Just not good enough, he said.

I believed him. I believed him even though my husband and I had been in a band for a decade and had three full-length albums under an independent record label.

What if all of it was bad, just because of me? I couldn’t bear the thought.

So I stopped writing music. I stopped singing. I stopped offering our worship leading services to the people with whom I came in contact, because they wouldn’t want us anyway.

And then, months later, I stood up, and there was a big, gaping hole where the music had been.

So I started crawling back to it, writing a song here and there. I started singing in the hallways of our home so my kids would smile at my silly lyrics that they hadn’t heard in too long.

I started to call that voice a lie.

///

Sometimes those words can hit us so hard we don’t think we’ll ever get back up. Sometimes it takes us a really long time to get back up. Six months. A year.

Six years.

It’s hard to say what makes people use their voices this way. Sometimes they’re jealous. Sometimes they’re just set on their own way and don’t care if getting that way is cruel. Sometimes they just don’t understand the responsibility that comes with their speech-freedom.

It doesn’t matter why, really. What matters more is what we do with their words.

Will we let them define a new, broken us? Or will we let them propel us into a new, better us?

Even though those voices shout loud and hit hard at all our weakest places, we don’t have to bend. We don’t have to break. We don’t have to let the stones inside.

We can let them drive us deeper into the journey of discovering who we are and what we can do, because we know, deep down, why we are here and who we are becoming and what we must do.

We know whether or not those voices and their words are true, and it doesn’t matter if they feel true in this moment right here, right now. It only matters that we call them FALSE.

Who would I be without writing? Who would I be without music? Fulfilled? Satisfied? Happy?

No.

Then I must keep on. No matter how many voices gather against me, no matter what those voices say, no matter how loud they get.

My boy has finished his grieving. I pull back only when several minutes pass without a sniff.

“Do you think your friends are right?” I say.

He shrugs. “I don’t know.”

“Do you think you would be happy if you didn’t write your Power Buddy stories?” I say.

“No,” he says. We look in each other’s eyes. “I want to tell their stories.”

“Then what are you going to do?” I say.

He’s quiet for a minute, and then he says, “I’m going to write their stories. Will you help me, Mama?”

Of course I will. Of course I will help my son prove to himself that he can do something others say he can’t.

Because I want him to know that “they” can’t tell us who we are or what we can or cannot do. “They” are not us. “They” have no idea why we have been put here.

But we do.

So every Wednesday night, during our snuggle time, we have been brainstorming my boy’s Power Buddy series.

We are telling those stories together, he and I.

Even though people said he couldn’t.

Even though people said it was stupid.

Even though people said no one would read them.

We do it anyway. Because we know.

We are doing what we were made to do, and this is wholehearted living.

by Rachel Toalson | On My Shelf

On my shelf this week:

Rump: The True Story of Rumpelstiltskin, by Liesl Shurtliff

Fairy Tales, by Hans Christian Anderson

Story Structure Architect: A Writer’s Guide to Building Dramatic Situations & Compelling Characters, by Victoria Lynn Schmidt

This week I’m reading an alternative story about Rumpelstiltskin (it’s cute), and, since I’m working on a series of fairy tale retellings, I’m starting with reading Hans Christian Anderson. Schmidt’s book will be one I take my time with. So much good information here that I’ll need to ingest slowly.

Best quotes so far:

“When you over-plot your story, you may lose spontaneity and feel like a slave to your overly detailed outline. When you build your story as you go, you tend to end up with a ton of subplots and loose ends that can’t be tied up and a character arc that flatlines. You need to have some direction as to where you are going, but you also need to feel free to write what your heart tells you to write.”

Victoria Lynn Schmidt

Read any of these? Tell us what you thought.

by Rachel Toalson | Fiction in Forty

The storm out the train windows was nothing to what he felt inside.

They had sent him away. Why would two people who were supposed to love him forever and ever give him up so easily?

Why didn’t they cry?

Ongoing challenge: Find (or take) a picture. Write exactly 40 words about it. Post.

(Great practice for brevity.)

by Rachel Toalson | Crash Test featured, General Blog

Sometimes I feel like I’m doing a pretty good job as a parent. Relationships are good, all those consequences we’ve put into our Family Playbook—a list of infractions and their expected consequences—are well understood, the house is in almost perfect order.

And then my children wake up.

It only takes seconds to realize that they are completely different people today.

Not only have they forgotten all the new infractions and consequences we brainstormed yesterday, but they also no longer care about getting to school on time or wearing clean clothes or keeping their room even the slightest bit tidy.

Yesterday my two older boys came down for breakfast fifty minutes before we had to leave for school. Today they were still not eating breakfast 10 minutes before we had to walk out the door, and I had to shout my last you’re-not-going-to-get-breakfast warning above the volume of an audio book, because I’m too lazy to walk up the stairs for the sixteenth time (I blame my laziness on my broken foot. And Post Traumatic Stress, which I feel every time I approach stairs).

Yesterday they liked the grilled broccoli and cauliflower and carrots we brushed with olive oil and sprinkled with sea salt and roasted in the oven. Today they gagged just looking at them.

Yesterday they all sat perfectly still in their separate spaces while their daddy read two picture books and I read a Narnia chapter book and again while we engaged in our ten minutes of Sustained Silent Reading time and then again while we did our meditation breathing and prayer time. We didn’t have to remind them once to get back in their spots or stop talking or that, no, an art journal is not a book you read and, no, the pen in your hand is not necessary during reading time (unless you’re taking notes—which he was clearly not).

Today they think reading time means chase-your-brother-around-the-library time.

It’s enough to drive a parent insane.

I’ve often joked that parenting is like living in an insane asylum. But the joke is usually true.

Insanity is defined by Albert Einstein as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

THIS IS WHAT KIDS DO, EVERY SINGLE DAY.

They try to write during story time, even though we’ve told them a billion times it’s not allowed. They try to sneak that LEGO toy into the bath tub, thinking this time will surely be different and we won’t object. They seem surprised that 8 p.m. is lights out, even though nothing has changed in their thousands of nights.

The problem is, our kids are the least consistent people on the planet. Every single day they wake up completely different people.

The bigger problem, though, is that they give us that one little taste of expectation realization, and we think they CAN sit still for two stories and a chapter book.

And we keep expecting it every other day.

For as long as we’ve had twins, I have fantasized about two boys napping in the same bedroom for more than an hour and a half.

We were spoiled, because our older boys took three-hour naps and could be trusted to sleep in their rooms with their doors closed.

The first time we left the twins for three hours with the door closed, they pulled down the forty-four shirts in their closet, painted with poop and ate the cardboard pages of Goodnight Moon.

So the next time I set a timer for two hours (because surely they’d just woken up early) and I sat outside their door to work on some deadline material. I could hear them shrieking, but we’d baby proofed everything, and there were only two mattresses on their floor (not even beds, because the twins could destroy furniture in 3.4 seconds). Nothing they could get into. Nothing that would hurt them. Nothing to occupy them for two hours.

They got really quiet, but I didn’t worry. We’re all quiet when we’re sleeping.

When the timer went off, I opened their door and found them sitting on clouds, all the stuffing ripped out of the lone Beanie Boo someone had left in their room.

The next day, I opened their door. I sat right outside. I corrected them when they so much as moved.

AND THEY FELL ASLEEP. FOR TWO WHOLE HOURS.

Oh, thank God, I said. It is possible.

So, of course, the next day, I did the exact same thing. Except as soon as they were asleep, I went to my room to do some more involved work and make a few business phone calls. Two hours later, they had knocked their closet doors off the hinges, strung all their ties from the ceiling fan and neatly lined up all their shoes under their mattresses.

Oh my word.

It’s maddening and confusing and impossible to keep up with these every-day-different children.

It’s impossible to know that today the 8-year-old only got seven hours of sleep but will wake up the happiest kid in the world, but tomorrow he’ll get 12 hours of sleep and will wake up gnawing on all the heads he bit off before breakfast.

It’s impossible to know that today the 6-year-old will follow all the rules and help with everything around the house, and tomorrow he will wake up a defiant little monster.

It’s impossible to know that today the 4-year-old will love reading those books to me but tomorrow he will wake up acting like he’d rather eat spinach than finish the last five sentences of that Little Bear story.

What’s a parent to do?

We just keep doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results from this insane asylum. Because, you know. Consistency and all.

Also because sometimes it does work, and those times it works might just be enough to power us through the times it doesn’t.

And if they’re not, well. At least there’s red wine. And chocolate.

And a lock on our bedroom door they haven’t yet learned to pick (it’s coming).

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

There are many great online blogs that use writers as contributors, but few of them with the reach of The Huffington Post. To get a spot as a blogger for Huff Post is one of the most desirable gigs a writer can get.

In December of last year I decided I wanted to start pitching blogs to some large-traffic sites. The first one I tried was Huff Post.

I had already done a ton of research, because I know it’s required before a writer can effectively pitch to a large publication like Huff Post (in fact, I recommend spending a few weeks getting familiar with the publication’s articles and the style and tone in which they’re written). I combed through the Huff Post Parents site, clicking on the features and trying to get a feel for what might do well on the blog. After a few days, I had an article in mind.

One of the great things about Huff Post is that blog editors accept previously published material, which means that what you post on your own personal blog can be used on Huff Post. My first pitch was an essay I’d written for my parenting blog, Crash Test Parents.

After digging around for a while, I found an e-mail address for the blog editors (blogteam@huffingtonpost.com), rather than the generic contact form (an actual e-mail address is always better). Then I crafted several versions of my pitch. It was my first pitch, and I wanted to get it perfect.

Here’s the one I finally settled on:

Dear Blog Team,

Thank you for taking the time to read my note. As a mother of five (going on six) boys, I hear many jokes from people who know me or don’t: “You know what causes this, right?” “Every time I see you you’re pregnant!” “Do you guys have a TV?” The most hurtful one, I think, is the “Well, my wife and I believe in family planning.”

So I wrote about this misconception in an article called “Just Because I Have a Large Family Doesn’t Mean I Didn’t Family Plan.” I have attached my piece to this message and greatly appreciate the consideration.

There are a few things I would do differently in this pitch today, now that I have so many under my belt. I would probably include a word count (Huff Post blog editors prefer blogs with 800 words or fewer). I would probably add a little information about me. I would change the word “hurtful” to “annoying.”

Five weeks went by and I heard nothing. And then, on the day I’d made a note on my to-do list to try another pitch (because if you fail, keep on trying), I heard from a blog editor, who asked me to join the Huff Post Parents team.

My first article printed at the end of January (almost two months after I pitched it), and was a feature right out of the gate. It resulted in more than 200 comments and more than 1,200 Facebook shares, 25 tweets and 17,000 likes.

I’ve been blogging for them ever since.

Huff Post doesn’t pay you for your blogs, but reusing your blogs can make that time worthwhile. They allow links to your original material, which can draw people onto your own platform (always the goal).

Traffic to my web site increased dramatically once I joined the Huff Post Parents team, because people who liked my article wanted to see what else I’d written.

Once you become a blogger for Huff Post, you get a blogger profile and can submit blogs as often as you want. I try to submit them at least once a week, although the publishing schedule varies, and I don’t always have one article posting every week. Sometimes blog editors are inundated with submissions and a blog can sit in a queue for six weeks or more.

One of the biggest drawbacks, for me, is that many of the people who comment aren’t always the nicest people. I tend to have a pretty thin skin, so sometimes it gets to me. But if you can step away and answer their unkindness with kindness, you win others to your platform.

Overall, Huff Post Parents and its other affiliates (I’ve since been published on Huff Post Education and plan to pitch a few to Huff Post Religion) is a good move for visibility and introducing others to your platform.

Important tips:

1. Make sure you have an engaging headline. If blog editors don’t know who you are, the first thing they’ll see in your pitch is the blog title. Make them want to read it.

2. Clean your copy. Make sure your copy is free of errors. It just makes working with you much easier for these editors who deal with thousands of queries and blogs every day.

3. Try and try again. If more than six weeks goes by, try another pitch. Keep trying until you get something accepted. But don’t keep trying without looking at what might be unappealing about your pitches–whether it’s the article or your e-mail. Analyze and learn from every rejection.

by Rachel Toalson | Messy Mondays

I fill this thing up every single morning. I swear. But at any point in the day, if I come downstairs to refill my Klean Kanteen, this container will be empty. Every time. Where is all this water going?

My husband blames the kids. My kids blame Daddy. What am I to do with this?

All I know is I’m really tired of doing the heavy lifting here.

Maybe I’ll just get my own and write my name on it with a big, fat permanent marker. “This water belongs to Mama,” it will say. “If you so much as touch it, you will owe me five minutes of alone-time.”

Wait. That’s not such a bad idea.

I’ll be right back.

(All half-joking-about-first-world-problems aside, there really are kids who don’t have access to clean water. If you want to help change that, click here.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

All day long I’ve been checking comments and shaking my head and feeling distracted by this war happening online, on my space, so I didn’t get much work done.

Many of the comments are kind, but too many of them are not.

So I sit down to my computer and get ready to fire back my responses. Something about how we should take care with our words and assumptions and especially strangers’ hearts.

My husband puts his hand on my arm. “It’s not worth it,” he says. “You can’t argue with people like that. You just have to ignore them.”

I scan the tirade one more time, and every single one of them pouring poison online holds up a “freedom of speech” card, claiming their right to share their opinion.

And yes, it’s true. We do have the right to our own opinion.

But just because we have the right to free speech and the freedom of expression, does that mean we should use it to air everything we think?

This is a harder question to answer.

///

When I was 11 years old, I stood outside the little Baptist church I attended on Wednesday nights and watched a friend play basketball with some of his older buddies.

Another girl watched, too. She had a crush on my friend, but he didn’t ever pay any attention to her, mostly because he had a crush on me. I didn’t see him as anything more than a friend, so I kept trying to bring them together.

But my efforts didn’t work. And there came a day when the youth leader called us all inside and the boys went one way and the girls went another, and my friend hugged me and said he was leaving early and wouldn’t see me again until school the next morning.

The girl was watching. The boys disappeared, and she turned to me and said, “You have a really pointy nose.” Then she walked away.

Maybe it wouldn’t have affected me as much if my dad hadn’t just left my family for another one. Maybe I wouldn’t have been as bothered if I hadn’t already been uncomfortable in my skin. Maybe I could have let it go if I hadn’t already been walking my way toward eating disorders and wishing I were different.

I can’t say for sure, because that wasn’t my reality then.

I tried to pretend her words hadn’t hurt me as much as they did. I tried to keep my fingers from tracing the shape of my nose. I tried to walk past the girls’ bathroom without ducking inside.

But I did go inside, and I stood looking at my nose in the mirror for five whole minutes, turning to examine it from every angle.

Yeah, I thought. Yeah, I see what she means. It is pointy.

If she thought it was pointy, how many other people did, too?

///

Even today, in my dark days, when I find myself unhappy with my appearance, her voice joins the others in their raucous chorus.

What does it matter? you might say. What does it matter what one little girl thought? What does it matter what other people think? You shouldn’t be so weak to care. You shouldn’t be so insecure about yourself that the words of another person can hurt you.

The problem is that we are all, at the heart of us, wired for connectivity. What exercising our freedom of speech and our right to our own opinions through personal attacks on other people does is it disconnects us from the human experience of community.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. It was the first global expression of the basic human rights all people could claim.

Freedom of speech was added as Article 19 in 1949. Article 19 said that “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

This idea of free speech and expression had been developing since the advent of the printing press. Traditionally, governments had limited printing materials to only those that the government agreed with.

Because of this limitation, political ideas could not be freely debated.

Free speech and the free expression of ideas was originally a political, intellectual right, not a personal one meant to justify airing our opinion about everything.

Governments still restrict freedom of speech and expression based on the harm principle, which says that one’s freedom cannot be used to harm another. Some of those restrictions include libel, slander, hate speech, fighting words and oppression. There are many others.

Article 19 also states that the freedom of speech and expression carries “special duties and responsibilities…for respect of the rights or reputation of others.”

This is the part we seem to have forgotten.

///

In college I worked as the editor-in-chief of the college newspaper.

There were a few rotating cartoonists who would publish editorial cartoons with us.

One night a cartoonist turned in his cartoon, and I immediately had a bad feeling about it.

In the cartoon, a professor stood at the front of the class. A bubble above him said, “Blah, blah, blah.” The students around him all had hostile expressions on their faces. Some were sleeping. A few were throwing things at him.

The caption below the cartoon said, “Mr. Smith puts his family to sleep, too.”

I called the cartoonist to see if he had anything else he could send me.

Why? he said.

Because this one just didn’t seem very respectful, I said.

It’s not a real teacher, he said. It’s just a joke. It’s just a humorous opinion.

He said he had nothing else to give me, and I was two hours from deadline with nothing else to fill the space.

So I let it run.

The next afternoon, when I got to my office, I had fourteen messages waiting on my phone and another seventeen in my e-mail inbox. People were outraged by the cartoon. It shouldn’t have run.

It seemed that everyone but me knew who the professor was, because even though the name had been changed, the picture, they said, was a dead giveaway.

I had to not only submit a formal apology for letting something so insensitive print in the paper for which I was responsible, but I also had to fire a really good cartoonist who’d probably just been annoyed at a teacher for some reason or another and decided to lash out in the best way he knew how.

Just because we have freedom doesn’t mean we should take it.

///

With this freedom comes great responsibility.

We are responsible for our words and whether they build up or tear down.

We are responsible for the hearts of one another.

In this day of computer communication, with our ever-increasing ability to comment anonymously all over the Internet, we have gotten really good at firing off responses, without really thinking about how, at the other end of our words, there is a person.

We can’t see their face. We don’t know much about their lives. We assume the parts that are missing.

It’s easy to forget our responsibility.

I don’t have a problem with a friendly exchange of ideas, with a person who can respectfully disagree with what I have to say, someone who makes a good effort to convince me of his or her viewpoint without feeling the need to make it personal.

But when someone starts attacking me or the members of my family, saying destructive, hurtful, dishonoring things they have no way of knowing for sure, that’s when they have lost their ability and their right to communicate with me.

What freedom of speech really means is expressing our opinions or viewpoints in a way that does not damage other people or people groups. It means carefully weighing our words and running them through a filter—is it kind? Is it true? Is it necessary?—and only speaking when our words pass the test. It means seeking harmony and peace even in disagreement.

We cannot claim our right if we do not exercise our responsibility.

Freedom of speech has the ability to broaden our minds in astounding ways, introducing us to new ideas and uncomfortable viewpoints and enriching humanity’s full experience of life.

We just have to know how to use it.

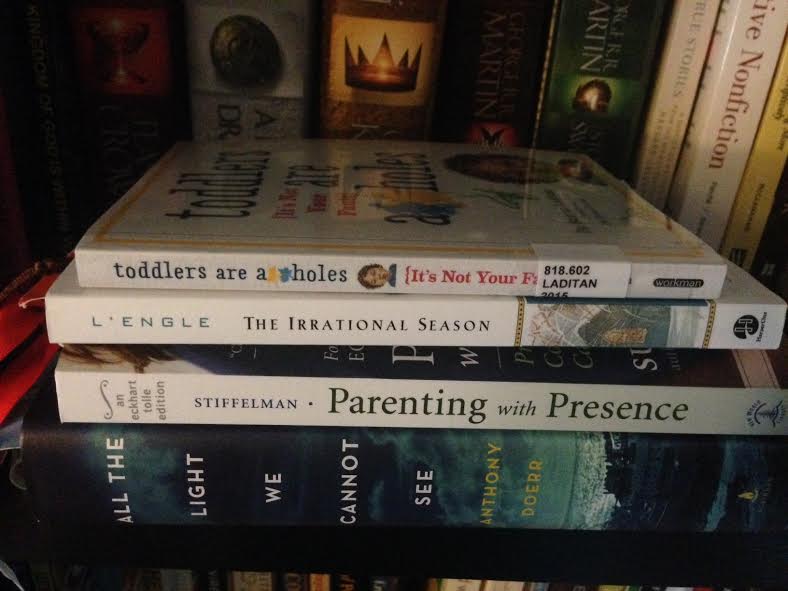

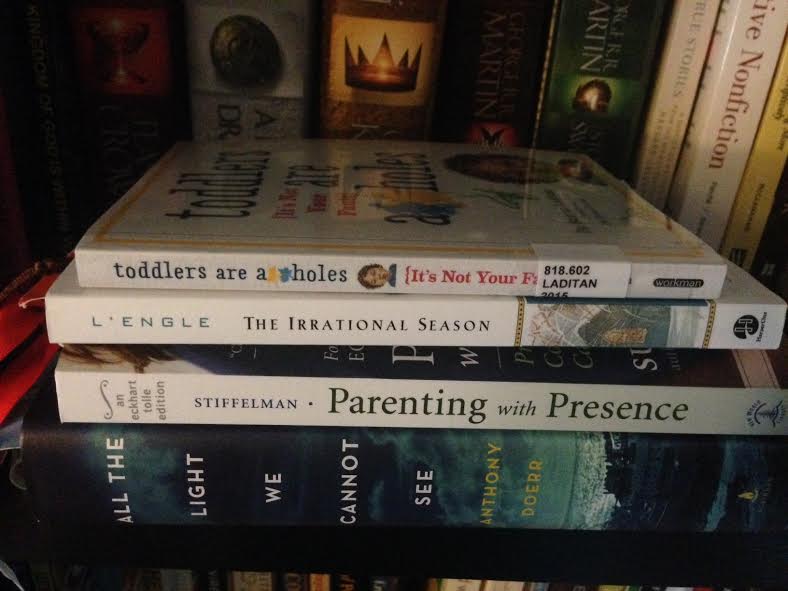

by Rachel Toalson | On My Shelf

On my shelf this week:

Toddlers are A**holes: It’s Not Your Fault, by Bunmi Laditan

The Irrational Season, by Madeleine L’Engle

Parenting With Presence: Practices for Raising Conscious, Confident, Caring Kids, by Susan Stiffelman

All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr

I’m not quite sure what to think of Bunmi Laditan’s parenting humor book…she’s very good at humor, though. I’ve been wanting to read this classic spiritual from Madeleine L’Engle for a while, so I’ve finally made time. I’m a big fan of Susan Stiffelman and her first book, Parenting Without Power Struggles, so when this newest one came out I knew I had to add it to the list. And I’m finally getting around to reading Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize winner. It’s beautifully written.

Best quotes so far:

“The Coming of the Kingdom is creation coming to be what it was meant to be, the joy and glory of all creation working together with the Creator.”

Madeleine L’Engle

“It is the nature of love to create.”

Madeleine L’Engle

“I find it a good discipline to practice believing as many as seven impossible things every morning before breakfast. How dull the world would be if we limited ourselves to the possible.”

Madeleine L’Engle

“Children who feel liked, seen, cherished—just as they are—are naturally more motivated to do what their parents ask; it is human nature to cooperate with those we feel solidly connected to.”

Susan Stiffelman

“Each of our children offers us opportunities to confront the dark and dusty corners of our minds and hearts, creating just the right conditions to call forth the kind of learning that can liberate us from old paradigms, allowing us to lead more expansive and fulfilling lives.”

Susan Stiffelman

“By looking at why your child’s behavior triggers you so deeply, you have an opportunity to heal something from long ago and grow into a more healthy and whole version of yourself.”

Susan Stiffelman

Read any of these? Tell us what you thought.

by Rachel Toalson | Fiction in Forty

We lived in the sky, on pillow clouds. No one knew, until that day a woman climbed to the top of our mountain. Grimmold didn’t warn us. We didn’t have enough time to hide.

I turned, and she was there.

Ongoing challenge: Find (or take) a picture. Write exactly 40 words about it. Post.

(Great practice for brevity.)

by Rachel Toalson | General Blog

Not long ago I fell down our house stairs and broke my foot.

It’s not often that I am sick or injured. I’ve taken two sick days in eight years of parenting—because my appendix was about to explode and, after vomiting all night, I thought it was time to have someone take a look at it.

As the only female in this household of eight, my boys form quite a force when it comes to taking care of Mama.

They fight over who gets to take the laptop up the stairs so I have a free hand to hold onto the stair rail while carrying the baby. They throw away dirty diapers so I don’t have to walk the thirty-seven excruciating steps to the trashcan. They draw me pictures and pick me flowers and leave sweet love notes on my pillow.

I appreciate their help and care. I really do. But, three weeks in, there are some things I can just do without.

For instance: the constant Shadow following me around, asking me if he can inflate my foot cast. Him, I can do without.

I let him do it once, and now, every time I take my cast off to rest my foot on the couch, he gets this excited gleam in his eye, because he knows, eventually, the cast will have to go back on. He knows, eventually, the cast will need inflation, because I have to walk to the kitchen to fix dinner.

I’m tired of being stalked by the Inflation Predator, son. Thank you for your help. But no.

There’s another predator who lurks in the doorway when I’m struggling in and out of the bath.

See, it takes me ten minutes to remove the cast and ease myself into a bath balancing on both hands and one leg, and it takes practice.

So my triceps weren’t as strong as I thought they were. So a few times I’ve slipped. Big deal. I didn’t cry out or ask for help or shout curse words like I did when I was falling down the stairs. I mainly laughed hysterically because I didn’t die in a bathtub.

I guess this boy thought I was weeping instead of laughing, though, because he’s always lingering just outside the door, close enough to hear my every move.

“I’d like to take a bath by myself,” I say. “With no one else around.”

“I’m just making sure you don’t fall,” he says.

I appreciate your concern, son. But please. Leave me alone. Let me take a bath in peace.

Then there is the predator who walks behind me on the stairs.

To be fair, all my boys are a little freaked out that Mama, normally so athletic and graceful (HA!) fell down the stairs and broke the second bone she’s ever broken. Even my husband reminds me, every time I approach the stairs, to be careful and take my time.

But there is one boy affected more than the others, so he has taken to walking one step behind me on my way up the stairs so he can catch me if I fall (as if I don’t weigh four times as much as he does and wouldn’t flatten him on contact).

This would be all nice and sweet IF he didn’t also feel the need to make comments about my appearance as we’re walking up the stairs.

“You wore those shorts yesterday, Mama,” he says. He laughs. “Did you?” He laughs again. “I think you wore them the day before that, too. Did you, Mama?”

Truth is, I’ve worn them for four days straight, because they’re comfy enough to wear to bed, and I can just roll out and not have to wrestle into new clothes while balancing on one foot.

“What’s that blue line on the back of your knee, Mama?” he says.

It’s called a varicose vein, baby.

“Why is it there?”

Because I had a lot of children.

“You’re really slow, Mama.”

Thanks for noticing, baby.

“And your booty is bigger than my face.”

Sometimes I think about falling backwards on purpose.

The twins have excused themselves from this “help Mama get better” phase. They actually are working harder to NOT make me well. They leave blankets all over the floor so I can trip over them. They “accidentally” step on the boot. They drop water on the floor without telling anyone so I slip and almost break something else.

The constant questions are another way my boys express concern.

“Is your foot still broken, Mama?” (I hear this a billion times a day.)

No, I just like wearing this good-looking boot.

“Can I wear your boot, Mama?”

Of course, dear. I’m only wearing it because I want to. Also, even though it comes up to your thigh, I’m sure you’ll find a way to walk with a stiff leg where others have failed.

“When will you get better?”

Well, kids, that depends a lot on you.

The predators and booby traps and questions can all get pretty annoying, but mostly I’m just glad they care enough to ask about my wellbeing. I’m glad they want to do what they can to help me heal.

Or maybe they’re just worried that we’ll have tossed salads for dinner indefinitely because I haven’t cooked a decent meal since it happened.

On second thought, that’s probably what it is.