by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

It happens unexpectedly, like everything else this boy does.

The oldest, the one who first stole my heart, sits on the side of my bed during our snuggle time. He is drawing some cartoons for the book we’re brainstorming, one we plan to write together.

He says it almost like an afterthought, like it isn’t a big deal, because he has no way of knowing just how big it is.

“I want to marry a woman like you when I grow up,” he says.

I laugh and touch his cheek, and he smiles wide into my eyes. “Really,” he says. “I’m not joking.”

I know he’s not, so I tell him so. And then, when the timer clangs and the baby starts fussing to be fed and he walks out, back to his room, I breathe deep and long, trying to keep the tears from dropping.

They do anyway.

Maybe it’s because the last few days he’s been walking around the house reminding us he only has eight more years before he’s driving and 10 more years before he graduates.

I’m just not ready for any of it.

I’m not ready for them to be grown. I’m not ready for them to be married. I’m not ready for them to be gone.

Sure, he’s only 8, but the day is speeding upon us, if the last eight years have anything at all to teach us.

One day he will be gone. One day they will all be gone. They will all be someone else’s.

This is all right and true and noble and sweet and beautiful. But there is a bittersweet piece to it.

They are all boys.

So I will lose them all.

///

When I was a senior in college, I came down with a severe case of the flu.

I had never before had the flu, in all my 21 years. My throat felt scaly and fire-filled, my cheeks turned red and I could not sleep my body hurt so badly.

My husband, who was just a fiancé at the time, stuck by my side, even at the risk of getting sick himself. He put a cold washcloth on my head to keep the fever down. He made me hot soup and fed me the two bites I could swallow. He took me to the emergency room when my fever got so high I almost passed out.

And then, when it just got too awful to bear, I finally croaked out, “Call my mom.”

Because there is just something about your mom knowing you’re sick that makes you feel just the littlest bit better. She doesn’t even have to drive the 123 miles to your college apartment or sit on the side of your bed or wait outside the room while you sleep.

She just has to know.

A few weeks later, my husband (fiancé) came down with a stomach virus and puked for days.

The only person he called was me.

His mother didn’t even know.

///

I ask my friends with grown boys all the time.

Does he call?

Does he visit?

Does he invite you to visit?

Do you know when he’s sick?

Do you know when he’s hurt?

Do you see him at all?

Most of their answers are the same.

Not often, they say.

I don’t know if it will be the same with my boys.

But I do know that the bond between a mother and a daughter in those growing up years grows right up with them. The daughters have children, and we begin to understand what our mothers sacrificed and how deeply she loved and just how hard it all was.

My boys will never know what it’s like to be a mother, only what it’s like to be a father.

They will never feel what I felt, that incredible awe at having grown this perfect little human being and how lovely it was to watch them nurse in the lamplight of my room and the way they whittled me into a better version of myself.

I used to think I was missing something, that this piece of mother had been withheld because I was not a good enough woman to raise a girl.

Now I know better.

Every child is a great gift, and whether or not we receive him as such doesn’t change the truth of that gift. They were all given so they could scrape us into the best versions of ourselves, and maybe they are boys and maybe they are girls, but they all scrape our hearts the same.

If my boys want to marry a woman like me someday, then I have to let them shape who I become.

///

When that first pregnancy test showed positive, and my husband and I could finally move again, my mother was the first person we called.

He was the first grandchild, so of course she was excited. She went to the second appointment with me and listened to his heartbeat. We recorded the first sonogram and gave her a copy. She called me every week, and I called her in between just to let her know how I was doing.

She was the one I wanted to stay with me after the baby came home so we could find our feet with this new little person. She was the one who comforted me when my milk never came in. She was the only one I trusted to keep him for the first overnight road trip his daddy and I took.

Having a baby just made our bond even stronger, and I ached to have a baby girl so I could one day share that with her, too. So I could tell her about the incredibly strong women whose line she shared.

Only it didn’t happen.

We welcomed boy after boy after boy, and the one girl who came slipped right through our hearts before we could meet her. And then came more boys.

Mother of a daughter is a title I would not carry.

///

This is our last baby.

I knew it was coming, and even though I felt disappointed at first that the baby I carried was a boy, I am so very glad that he is another boy.

But.

There is still a deep longing for the daughter I lost, for the bond I missed, for a lifelong friendship like the one I share with my mother.

People ask all the time, when they see or hear that we are the parents of six boys: “Did you want a girl?”

The answer is of course.

Of course I wanted a daughter. Of course I wanted to raise a girl to know where she stands in a world that was made for men. Of course I wanted to raise a girl to know she didn’t have to do anything at all to be proved worthy. Of course I wanted to raise a girl so she would know she was beautiful even in all the imperfect places.

It’s not the reason we had six children, but I did want to be the mother of a daughter.

A daughter shares something so very special with her mother, and I wanted this.

She shares the experience of watching her mother put food on the table, day after day, week after week, year after year, and knowing a little something about this overwhelming need to provide them with everything they need.

She shares the experience of seeing her mother sitting in the stands at all her basketball games, even the one where she sat the bench for too many aggressive fouls.

She shares the experience of accepting a “secret” engagement and understanding, later, that her mother knew all along, because a mother always knows.

I will never have a daughter to experience a first heartbreak with, and I will never have a daughter whose engagement I know about first, and I will never have a daughter bounce career ideas off me.

I will not be the one they call when they are sick. I will not be the one they open up to about the girl they think they might love. I will not be the first one to know they are getting married or having a baby or what gender the baby will be or what they’re doing for Christmas or how long he’s had the flu.

It’s okay to grieve this, because it is a hard knowing.

And it’s only in admitting what we want and how we didn’t quite get it exactly that we can clear our eyes enough to see that what we want and what we need are two very different things.

So I am a mother of only boys.

This is something wonderful, too.

///

One day my boys may marry a woman like me.

And I will be right there, cheering from the sidelines, next to their daddy, waiting for them to call me or visit me or share with me—or not.

Whatever that future holds doesn’t change the truth of now: I have been given a great gift, because I am a mother.

I don’t have to live in those future days now. I don’t have to pretend I know how they will end up. I don’t have to look at my boys now and see them all grown up, pulling away, because the truth is, I have no idea what grown up will look like.

I just know that right now they are my boys.

They are my boys right now.

One day they will be gone, but that isn’t today.

So today I will enjoy being the mama of these boys I love so much my heart is near exploding.

I will enjoy being the first one they run to when they’re hurt and the first one they tell when they have some exciting news and the only one they want to hold them when they’re sick.

Yes. This is something wonderful, too.

by Rachel Toalson | On My Shelf

On my shelf this week:

You Are a Writer, by Jeff Goins

Allegiant, by Veronica Roth

Family—The Ties that Bind and Gag! by Erma Bombeck

This week I’ve got a writing book, the last in a dystopian series by Veronica Roth and another from Erma Bombeck (I just can’t stop reading her…she’s hilarious.

Best quotes so far:

“Writing is mostly a mind game. It’s about tricking yourself into becoming who you are. If you do this long enough, you begin to believe it. And pretty soon, you start acting like it.”

Jeff Goins

“You show me a boy who brings a snake home to his mother and I’ll show you an orphan.”

Erma Bombeck

Read any of these? Tell us what you thought.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

It took me way too long to call myself by what I am: Writer.

Because I worked another job, and I had a title there—journalist—and what I did in the margins—writing—wasn’t really who I was.

Or at least that’s the lie I believed for years.

I tried to do without writing, for a time, because there were babies, one after another, and the margins felt cramped and tight, but the need to write always blazed from within.

Creating something from nothing, arranging and rearranging words into art felt good and right and true, but when people asked me what I did, I gave them my job description—“I produce a newspaper.”

Because producing a newspaper seemed like a more viable job than “writer.”

And then I lost my job.

I stumbled along for a while, worried that I would not have anything to say to people when they asked, “What do you do?” because I had no “real” job.

I had the writing I did in the hours I could manage it, but I knew that wouldn’t satisfy them. I was not published, at least not beyond magazines and newspapers. I was not legitimate.

I didn’t create rain or shine, eight hours every day, because there were always babies crying and dinner to prepare for perpetually-hungry children and fun days to plan on the weekends, when we were all finally together without work pressing in on us.

And yet I still wrote consistently. Every day. Some days it would look like opening a journal and jotting 200 words down before a kid started screaming, but I was still doing the work. I was still showing up.

I was a writer.

I wrestled with that question, “What do you do,” for a couple of months before I finally found myself able to answer, simply, “I write. I am a writer.”

We can feel like phonies tossing those words around. Writer. Dancer. Singer. Painter. Sculptor. Artist.

Because doesn’t everybody do it now?

Aren’t all the arts incredibly accessible to all people now?

Of course they are, but that does not make me any less of one.

I am a writer because I do the work. We are artists because we do the work. So we should start calling ourselves by our true names.

It can feel uncomfortable, because we don’t think we’re legitimate, maybe, or because we don’t have a publishing contract or ten million followers or unlimited hours to pursue our craft.

But the truth is, all we have to do is show up. Every day. For ten minutes or ten hours.

Maybe it takes us a few months to settle into that name, but when we are brave enough to try it on for size, we will see that it really does fit.

We will see that we become what we speak over ourselves. When we call ourselves an artist, we will become an artist.

There is something about calling out our true nature that helps us live into it.

So we must let go of the fear. We must dismiss the fear of what “they” might think. We must dismiss the fear of what it might mean, the commitment it might demand (and it will commitment. But if we love it, commitment will come naturally). We must dismiss the fear that we are not good enough to call ourselves by our true names.

We are good enough.

Becoming an artist is more about what we do than anything else.

Do we create on a daily basis?

Yes.

We are artists.

Do we show up for the work even when we don’t feel like it?

Yes.

We are artists.

Do we burn to pursue the art that lives inside us?

Yes.

We are artists.

It really is simple. But we must first climb over that mental mountain that says we may not be who we say we are. And this takes everyday work, every day pulling out a notebook and writing, pulling out an art book and sketching, pulling out a guitar and tinkering with that new song.

Artists become artists in the practice.

So let’s get practicing.

Challenge: Wear your artist hat for a week. When someone new asks you what you do, tell them you’re a writer or a painter or an actor or whatever you are, at your deepest place. Sometimes saying it aloud to someone else helps us believe it more easily.

by Rachel Toalson | General Blog

They say sleep deprivation is a lot like walking around drunk.

That must be why I keep running into doors and passing out on the couch and forgetting where in the world I put the baby’s clean diaper when it’s literally right in front of my face, and I’m looking at it and it’s looking at me.

After the first baby, all those people who have walked in our shoes give us that helpful advice: “Sleep when the baby sleeps.” And if you’re like me, you don’t realize they’re serious until you’ve spent 60 hours awake.

People also give this advice after baby number two and baby number three, which always makes me wonder if they ever really had more than one.

It’s just not helpful advice once you’ve passed the first baby.

Kids, you see, at least a tribe like mine, need constant supervision. The only time I sleep is when they’re ALL sleeping. Which is never.

(Actually that’s not true. My kids sleep like champs. In their beds by 8:30, the first one usually falls asleep by 8:45, and the last one by 10, and then that first one will wake up by 6. Which leaves me a whole four hours for sleep, after I finally wind down from the thirteen times I almost dropped into dreamland only to hear a knock on my door from the one who needs to tell me about that new character he’s developing for the story he’s writing or another one who needs to tattle on a brother for kicking him in the face or another who just wants his third kiss goodnight.)

Sleep while the baby sleeps.

Oh, I wish it were that easy.

Once, when I slept while the baby was sleeping, my 8-year-old, 5-year-old and 4-year-old boys climbed to the top of our minivan parked out front and decided to see what it would be like to pee off the top, in clear view of every house on the block (sorry neighbors).

Another time I passed out involuntarily, I woke with a start, five minutes later, because I heard something clinking in the background. Turns out it was my 2-year-old twins, racing out the back door with knives they wanted to use for sword fighting.

And who could forget the time I took a twelve-second nap and my 5-year-old ate two pounds of grapes.

Sleep while the baby sleeps.

It’s just not helpful anymore.

Another piece of used-to-be-helpful advice that is no longer relevant after the first child: Take care of yourself.

Well, see, I tried it one time. I tried putting up my feet for 10 minutes of quiet in my bedroom. Just 10 minutes. When I came back out there were 100 paper airplanes scattered all over our living room floor.

Another time I went to the bathroom for no more than two minutes, begging my pee to flow faster, and my third son located a black permanent marker and turned his yellow shirt into a black-and-yellow striped shirt.

And then there was that time I felt brave enough to rinse off in a fifty-two-second shower, and my 5-year-old used the time to cut a chunk out of his hair, draw whiskers on his face and glue his hand to his shirt.

“Hold him all you can,” they say.

I tried holding him every minute I could. And then a 2-year-old figured out how to open the under-sink cabinets, even though they’re baby proofed, and sprayed vinegar cleaner all over the floor so his twin brother would slip in it and bust his head on the tile floor.

There was that time at the children’s museum I tried to hold him and stare in his eyes for five seconds or so, and the 2-year-olds snuck into an elevator and we searched for them for twenty whole minutes, nearly giving them up for lost before the elevator door dinged and out they came running with grins on their faces and not enough vocabulary to tell us what exactly they were doing in there.

Once, when I thought I’d feed the baby in the privacy of my room so we could share some one-on-one time, because the 2-year-olds were sleeping, one woke up, unbeknownst to me, and colored his entire door red. (It’s still a mystery where he found the crayon, since they have NOTHING but beds and clothes in their rooms. I think he was hiding it under his tongue.)

OK, kids. You win.

I just can’t use all that well-meaning advice anymore.

When I was talking it over with my husband, trying to figure out a new plan, some way we might be able to sleep while the baby was sleeping and hold him all we could and take care of ourselves, he looked at me for a minute and said, “Maybe we should just invest in some kennels.”

I think he might be on to something.

by Rachel Toalson | Messy Mondays

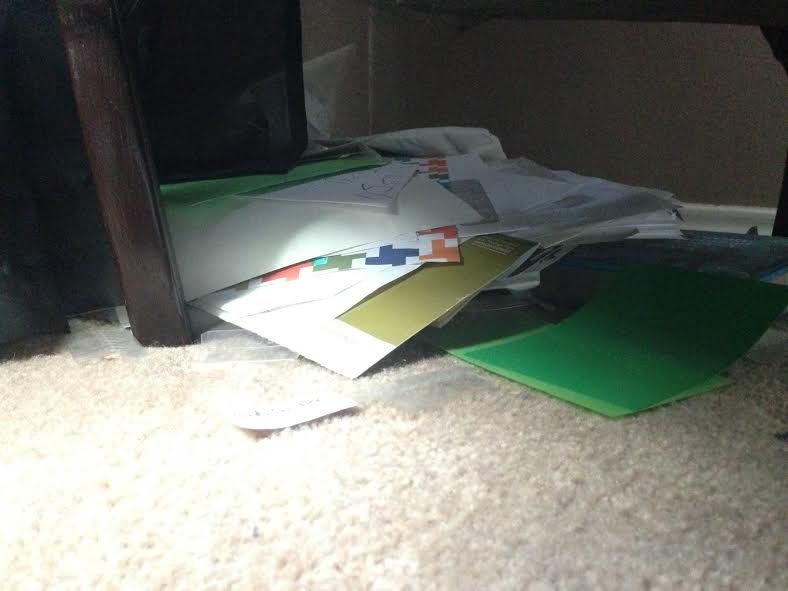

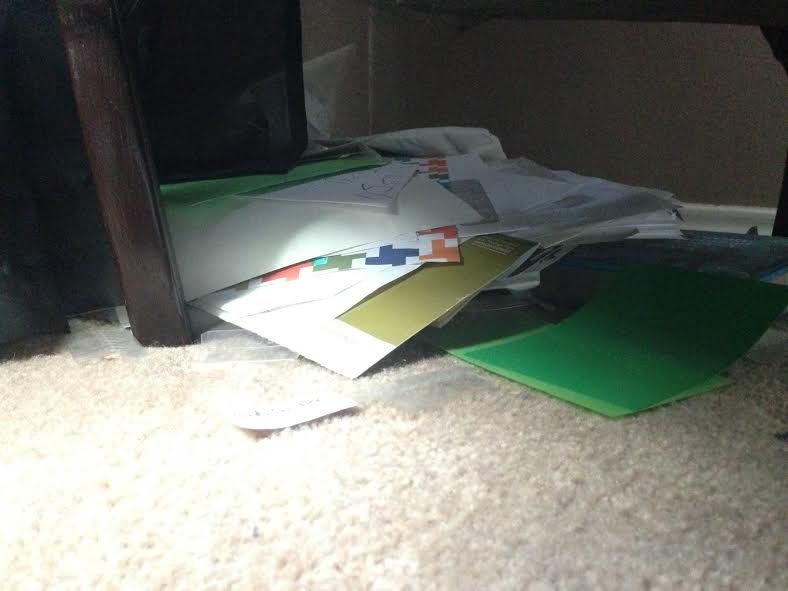

Do you have this one place in your bedroom where you once put a stack of something you didn’t know what to do with (papers that should probably be filed away, but it’s just so much effort) and told yourself you’d clean it up another day and now it’s been two years?

Yeah. Me neither.

No, that’s not my second-grade son’s kindergarten report card under my wing chair. No, that’s absolutely not an old water bill we forgot to pay. No that’s not a library book we’ve had missing for years.

Just pretend you didn’t see this dirty little secret.

After all, that’s what we do.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Photo by Helen Montoya Henrichs.

We’re sitting in my living room, all our bellies full, and the twins are down for their naps while the oldest boys and the newest one are still up, hanging out with their Nonny and Poppy.

My mom holds the littlest one. My stepdad plays with the others.

And somewhere in the middle of our conversation my mom says, “I sure never expected you to have six boys.”

I laugh. “Yeah. Me neither,” I say.

“If your high school friends could see you now,” my mom says.

If they could, I thought. They would not recognize this me I have become.

I am not who I once was. Not even close.

And I am so very glad.

///

When I was 12 years old, I had just lost my dad to divorce. My mom was close to depressed. I lost my center.

I was never exactly popular, but I did have a handful of friends.

And there was a best friend. We were inseparable. We stayed over at each other’s houses—mostly hers, because I was ashamed of my poor. I knew her sister and mother and father, and she knew my brother and sister and mother.

And then there came a day when jealousy flashed its ugly grin and I fell in its web. I don’t know why, exactly. I just know that I was a fatherless child who was lost and alone and sad. Maybe that explains why it happened. Maybe it doesn’t at all.

There isn’t really a good excuse for being a mean girl.

It’s just that I hurt so badly inside that the only way I felt like I could deal with my hurt was to hurt someone else. So she could feel what I was feeling. Except I was too young to understand that when you hurt someone else, you don’t feel any less alone. You don’t feel any better.

We were watching the eighth graders play a volleyball game. Our seventh grade team had just finished. For some reason I was sitting up high in the bleachers, and she was down at the bottom. Probably I had already said something mean, because she was never one who did that.

More mean was on its way.

A mutual friend moved between us. “Why don’t you want to be her friend anymore?” she said when she reached the top of the stands.

“Because,” I said, with my poker face on. “I just don’t like her anymore.”

Our friend walked back down the bleachers and relayed my message, because we were immature little girls using a mediator, and I watched my best friend’s face crumble, her heart breaking that I could just decide one day I didn’t like her anymore.

And why not? A daddy could decide he didn’t like a little girl anymore and up and leave.

I spent five more years in the same school as my former best friend. Our friendship was never the same.

I could not ever quite bear to look her in the eyes.

///

It’s hard to say what changes us.

Love. Children. Years.

Life.

All of those, rubbing at our edges and softening up the rough parts and uncovering the diamond of who we really are.

We are born into the world pure and whole and beautiful, and then we start counting birthdays, and between those first days of life and now, the diamond of our identity starts disappearing little by little, covered by ego and pain and anxiety and fit in and popular and ridicule and normal, whatever that means.

Someone tells us we need to lose a little weight, and we forget that skinny does not equal beautiful. Someone tells us we need a thicker skin and we forget how big emotions can be a great gift. Someone tells us we aren’t any good at something and we forget that opinions are just opinions and we don’t have to be bound by them.

We forget that we are in charge of who we are and who we become, not “them.” Not our circumstances. Not all the hell that has happened to us.

We can spend a whole lifetime trying to uncover that diamond again.

I look back at the girl I used to be, the girl who could hurt a best friend with such irreverent, ugly words, and I am so glad I am no longer her but have become someone much more careful with words and the glass hearts of those I love.

I look at the teenager who lashed out and tore down and felt diminished by another’s success, and I am so glad I am no longer her.

I look at the young woman who never wanted kids because she didn’t want the changed body that came with them, and I am so glad I am no longer her.

I am not who I once was.

///

I would do more over the years. I would hurt other friends. I would say things I didn’t mean. I would try to make them feel what it felt like to live in my skin—rejected, ugly, unworthy.

And then I would find myself on my knees in the middle of a concert hall, moved so deeply by the music that I could not even hold my heaped-with-guilt head up anymore. I could not look into the eyes of the ones there with me. I could only sob.

And I would go back to my dorm and scratch out all my letters and dig through an address list of my old high school classmates, searching for the ones I needed. I would mail those letters off.

I would wait.

And the responses would come, one after another, telling of how touched they were that I had written and apologized, as if I could do anything else, and I would feel some small piece of healing bloom in my heart.

And then, not long after that healing set in, the same thing would happen to me.

A best friend would lash out. She would accuse and hurt and rip me clean apart.

And, God, it would hurt. But those places of forgiveness that others had extended to me would turn into places where I could forgive her, years later.

Because, even then, I was not who I once was.

///

There is a wisdom that comes with love and children and years and life, but we can miss it.

We can miss it because we are bent beneath the weight of guilt for all those things we did before. We can miss it because we are listening to who “they” say we should be. We can miss it because we are walking broken and we are walking breaking, like wrecking balls crumbling anything they touch.

The years twist some of us into smaller versions of ourselves, because they march on hard and violent and unfair.

But the good news is, we get to stamp The End to that victim story. We get to choose to become someone better.

We can heap more dirt on top of that diamond or we can uncover more of its brilliance.

It’s entirely up to us.

It’s not ever easy leaning into our transformation, and it’s not ever comfortable getting scraped and rounding off our edges and cutting out the pieces that no longer belong, but where we end up will be worth all that pain.

Because we will be someone greater, someone truer to ourselves, someone who knows what it’s like to be on the wounded side and the wounding side and has lived to tell about it.

The world can’t help but be changed by our changing.

We are not who we once were. We will never be again.

Thank God for that.

by Rachel Toalson | Stuff Crash Test Kids say

Identity crisis

Zadok (2): “Daddy a boy and Jadon a boy. I not a boy, I a twin.”

My poop scared me

Jadon (8): “Mama, I sat down to poop today, and it sounded like a gunshot when it came out.”

Mama: “Wow. That’s quite interesting…information.”

Jadon: “Yeah. It scared me. I don’t want to ever do that again.”

April Fool’s Fun

Asa (5): “Mama, I got on red today.”

Mama: “Really?” He looked really crestfallen, this boy who hardly ever gets in trouble.

Asa: “April Fool’s! Actually, I got on purple. That means awesome.”

Mama: “How exciting for you!”

Asa: “April Fool’s!”

Jadon (8): “I walked home from school by myself.”

Mama: “No you didn’t.”

Jadon: “April Fool’s!”

Hosea (4): “Mama, I lost my shoe on the way to pick up Jadon and Asa.”

Mama: “Then why is it on your foot?”

Hosea: “April Fool’s!”

These “jokes” went on for ten minutes, before I had to close them down.

An orphanage is better than home

Jadon: “I want you to drop me off at an orphanage.”

Mama: “You think an orphanage is better than living with Mama and Daddy?”

Jadon: “Yes! You’re that bad to me.”

(Because we told him it was time to clean up his LEGOs and come participate in story time.)

That’s some motivation

Daddy: “So I’m going to work out four times a week, and every time I do a workout, I want you guys to celebrate with me. What are you going to do to celebrate?”

Asa: “I’m going to turn into Swift and run to Ms. Hevner’s house and get some infetti eggs.”

Mama: “What kind of eggs?”

Asa: “Infinity eggs?”

Jadon: “Confetti eggs, Asa.”

Hosea: “I’m going to clean off the dining room table and wipe it with sprayer.”

Daddy (trying so hard not to laugh): “And what are you going to do to celebrate with me, Jadon?”

Jadon: “I’m going to attack you.”

And he did.

by Rachel Toalson | Fiction in Forty

Here, he says. It’s all I could find.

Where did they come from? I say.

You don’t need to know.

He’s right. I don’t need to know. I just need to feed our dying girl whatever there is to eat.

Ongoing challenge: Find (or take) a picture. Write exactly 40 words about it. Post.

(Great practice for brevity.)

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

I wear many hats.

There is the Mama hat, which includes all those others hats: Hurt-kisser, nose-wiper, diaper-changer, listener, teacher, discipliner, cook, meal planner, encourager, homework-helper and so many more.

And then there is my creative hat: Writer.

Often, these two hats seem to be in conflict with one another.

When my oldest two boys get home from school, the first thing they do is come to my room to tell me about their day. I love this, except that I’m typically deeply entrenched in some essay or a novel chapter, and the sound of my bedroom door opening pulls me right out of my creative flow.

I used to feel so annoyed about this. I talked to my husband about it, because afternoons are his shift with the boys. We came up with a plan—wear headphones, ignore the boys, lock the door, explain that this is work time, not talk time.

Still it kept happening.

The thing about kids is when they have something to tell you, they will plow right through any locked door or hasty explanation or music filtering through headphones to say what they need to say about that picture they got to paint in art today.

Balance is one of the most difficult aspects of being a parent and a creator. Sometimes we fall into the trap of believing that one cannot possibly exist with the other.

But here is something I have learned in my eight years as a parent: Children make our creating so much richer.

It doesn’t even have to be our own children. It can be a friend’s children or our sister’s children or the children who play outside our apartment. It can be a child we see in a restaurant or on the bus or running wild in a park. It doesn’t matter. Our interactions with them will always make our art richer.

You see, we used to be children with wild and crazy imaginations. We used to believe in the impossible. We used to dream big, incredible dreams.

And then we grew up and traded all that for a more realistic plan, because someone told us that’s what adults do.

Your head doesn’t belong in the clouds anymore, they said. It belongs here on earth.

That’s not a profession, they said. That’s a hobby.

You can’t write or paint or sing about that, they said. It would be silly.

But children. They’re allowed to be children. They’re allowed to believe and imagine and dream and create, without any limitations. The whole world is a giant field of possibility.

The truth is we create using the child who lives within us. So what makes us more prolific and artistic is connecting more deeply with our inner child.

Who can draw out that inner child most effectively?

Children.

My children are the ones who crank up that heard-it-a-thousand-times song on Pandora and can’t help but move their bodies to the music, pulling me into the dance party with them. They are the ones who sing those made-up songs, about how 1953 was the year of heartbreak, without a care for whether those lyrics make sense or not. They are the ones who create whole worlds in their imagination and share those imaginings with me so that my creativity feels ignited and new.

Just this morning, on his way out the door for school, my oldest, who is 8, brought down a box. A stuffed animal crouched inside.

“This is a portal,” he said. “Whenever my animals go inside, they are magically transported to another land called Hyrule.”

Yes. I want to be like the children.

So these interruptions of my children, when they need a mama and she’s working, are not really interruptions at all.

They are opportunities to enrich my work.

I don’t have to be writer for a certain number of hours a day and Mama for the rest. I can be both all the time, because one enriches the other.

I sure am glad for that.

Challenge: If you are a parent (especially one who works from home), next time your child interrupts, try to see it as an opportunity. What can you learn from this exchange? What might focusing fully on your child even in the interruption do for your creativity? Many times our attitudes about something just need gentle redirections. So redirect. Play. And watch your creativity explode.

(If you’re not a parent, spend some time with a child this week and see what you can learn from him/her about creativity. You might be pleasantly surprised…and significantly changed.)

by Rachel Toalson | General Blog

Dear Dr. Brougher,

I miss you when I’m not pregnant.

I know it sounds a little crazy. You, the doctor whom ever woman dreads that one time a year, because there are stirrups and cold metal and paper-thin sheets to cover everything and nothing at all, but I mean it. I really do.

This last time around, when I learned there would be another baby, part of my excitement was that I would be able to see you again, that you would share, once more, in the most joyous, scary, beautiful moment that can happen in the lives of a man and a woman.

I wonder if you know just what you have done.

The first time I met you, I was three months married, coming on the recommendation of a friend. You sat me down in your office and told me you’d been a former journalist, because I was one, too. It was the beginning of a friendship.

I asked you all sorts of questions about sex, the ones I’d never been able to ask my mother, and you answered them all in that direct, no-nonsense way of yours.

And then you sent me off with a “See you next year,” and you did see me the next year and also four months after that, when I took my first pregnancy test and it said yes. You may not know it, but I drove 115 miles to see you for that first prenatal appointment, because even though we’d moved to another town, I couldn’t imagine anyone else delivering my first.

And it’s a good thing, too, because there I was in the hospital, three hours pushing and no baby, and when my eyeballs felt like they might explode from the brutal strain, you told me you needed to use a vacuum to get him out.

I went crazy. I cried about how a friend who was a nurse in neonatal intensive care had seen so many cases of brain damage because of the vacuum. “Just don’t let them use a vacuum,” she’d said just two days before I lay on a bed in labor.

You did not laugh at my fear. You took it and held it gently. “That has not been my experience,” you said. “But it’s entirely up to you.”

Those contractions kept coming so I had to scream out, “Whatever you need to do, just get him out,” and you did, and he was fine, and you slipped out of that birthing room quietly, because a new mama and daddy were having the moment you’ve seen a thousand times, and the last thing you wanted to do was intrude. We didn’t even have a chance to thank you.

We would have more chances, though.

You would be my rock that this-is-the-safe-day when you ran the wand across my belly and there was no heartbeat, the same day you would deliver a baby and instead of placing her in my arms you would place her in a lab jar.

You would walk us through a twin pregnancy, a high-risk, share-the-placenta case that has more pages of what could go wrong than what could go right.

You would carry me through this last one, and maybe this is the most significant of all.

You see, I didn’t know if he would make it. There was that pregnancy condition, when I itched all over day and night. The condition that made me want to scratch my eyes out. The condition that could end in stillbirth.

And, God, I couldn’t do that again. I couldn’t lose another one.

I cried after every appointment near the end. I had anxiety attacks when he stopped moving for a minute or two. I dreamed about a baby whose face I would not kiss alive.

I sent you notes. I begged you to deliver early, since I’d read all about those stillbirth chances and how they increased the longer babies lived in a womb. I became the patient no obstetrician wants.

And then, the day before my birthday you gave me a gift. A baby, and he was ALIVE.

I love you for that.

I just had my last post-pregnancy appointment with you, because this boy was always going to be our last, and you don’t know it, but I felt all torn up inside.

Because the truth is I will miss you.

I will miss your humor. I will miss our talks. I will miss sharing in this new life experience with you.

I don’t even know that words can express how grateful I am to and for you, but I will try.

Thank you for all you have done.

You saw the fear in my eyes for that first one, and you spoke courage and peace and wisdom. You felt the sorrow of that lost one, and you spoke comfort and hope and healing. You knew the fear and worry that can consume a mama when stillbirth looms, and you spoke calm and understanding and love.

This cannot be underestimated.

Maybe it’s not what typical doctors do, this caring enough about a patient to ask about the lost job and the writing pursuit and the husband at home, whose name you remember, but you were never typical.

You were exceptional.

Not only did you deliver new life into the world, but you delivered new life into the heart of this mama, who did not know if she could really do it, any of it.

I will not be the same because of you. My family will not be the same. We are forever changed.

So thank you. Thank you for your gift of life. Thank you for sacrificing weekends so you could deliver every one of my half-dozen boys. Thank you for your love and care and constant concern.

You are a healer in every sense of the word.

Thank you for being you.