by Rachel Toalson | Books

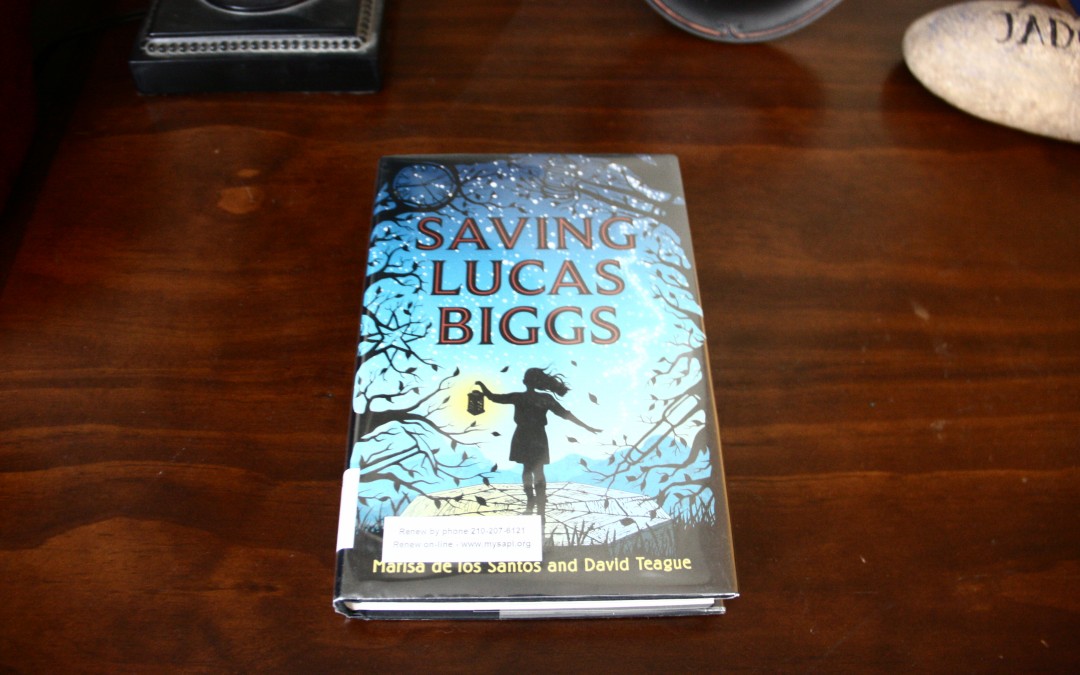

Saving Lucas Biggs (MG sci-fi), by Marisa de los Santos and David Teague, has been on my reading list for a while. I listened to half of this one on audio book and then read the rest of it, because I found it hard to jot down notes and locate quotes when I was only listening to the audio. And because there were so many passages I wanted to highlight, I had to switch to the hard copy version.

The story begins in a compelling way: with a trial and a guilty verdict. We learn early on that the trial is for 13-year-old Margaret’s father, and, also, that he didn’t commit the crime. This immediately sets up a reason for readers to continue reading. What’s going to happen to her father? Will Margaret be able to save him?

Not only that, but the judge who proclaims the guilty verdict and the impending death sentence is named Judge Biggs. Because he shares the same name as the title, the title becomes another reason readers keep reading—is he Lucas Biggs? Why does he need to be saved?

The story flips back and forth from the perspective of Margaret, who lives in present day, to Josh, who lives in 1938, when Judge Biggs was a young boy. Margaret, who can time travel, tries to prevent her father’s sentence by preventing the chain of events that caused Judge Biggs to become who he is today.

The only problem is, history is trying to work against her.

What I loved most about this book is that it told a story of innocence and good that was corrupted by power and disappointment. It told the story of a boy who was enticed to act outside of who he was because of circumstances that felt too painful for him to bear. It told the story of good and evil in a way that showed evil is not born evil but sometimes comes about due to circumstances or ignorance or desperation.

The authors crafted their two different voices beautifully. Here is Josh, talking about a miner’s strike and a subsequent massacre:

“After the massacre, our job was to keep Canvasburg alive, because if we left, or starved, or froze in the fall wind that’d started cascading down Mount Hosta, everything that’d happened to us would disappear into thin air, and everybody who’d died would’ve died for nothing.”

He’s a valiant child, one who believes in what the miners are doing, because they’re not treated justly. They must demand justice. He doesn’t think their town will be served by giving up. It’s a very heroic standpoint, after so many died because of what they believed. In spite of fear, he believes the miners are right to keep fighting for what they believe.

Here’s a descriptive passage from Josh:

“Fall kept falling, and the desert nights grew cold. I got to thinking that if we stacked rocks around the edges of our tents to stop the mountain wind from whistling straight through them, then maybe our blankets wouldn’t blow off in the middle of the night while we tried to sleep, leaving us dreaming of glaciers and hugging our knees. What I didn’t foresee was how hard it would actually be to find a rock to pick up. Even one. I mean, the desert around there, the whole shimmering thing, was like a work of art. It should’ve had a guard in a uniform with a sign: Do Not Touch.

“It was perfect. It was beautiful. Red! Green! Yellow!

“Brighter than you ever imagined! Every rock fit into every other rock like the pieces of a mosaic.”

This description endeared me to Josh, because it contains so much hope. That time of year, the desert was a perfect work of art. It was beautiful. Beauty can always be found in even the most dire of circumstances. Josh and his family is camping outside their town, and they don’t have much to eat, and they’ve just lost a bunch of their friends and neighbors, and still he’s able to find beauty in the landscape.

In Josh’s description of his brother’s chronic cough, you hear how much he knows and loves his brother:

“The shadow that fed on Preston’s cough grew like a storm loud over us. ‘I’m not complaining,’ he said one night before bed. And that was true. Preston had a nonstop mouth, but he never used it for complaining. ‘I’m just hungry.’

Josh gives us great characterization of his brother. It’s clear that he cares about his brother and that he is worried about the cough that has come back around, even though it was supposed to get better in the desert.

Here Josh is speaking about the day’s beginning:

“I watched the first sunlight of the day boiling over the desert like a tide of red falling up to drown me. I held my breath, as if that would save me, but I couldn’t go without air forever, and as I breathed again, a ruby crescent peeked over the rim of the world. In seconds, it had grown into a scarlet crown; then it was half an orange globe, and then a yellow ball, huge, glued to the horizon, and thwack, the ball pulled itself loose and floated up into the blue sky, burning whiter as it rose.”

The way he describes the sunrise is captivating; it’s as if I’m watching it with him.

And here Josh is speaking of Margaret, when he sees her for the first time after she’s done her time-traveling thing:

“Suddenly, I spied a girl. I’d never seen this girl before. I’d never seen a girl like this girl before, flitting from tent shadow to tent shadow. She had hair as red as the sunlight that’d just singed my retinas. She had eyes so green, I could see them fifty yards away, and her feet were really large.”

What he chooses to highlight in his description—the green hair that tells him who she’s related to in that small town, the red hair that also gives a hint of this ancestry, the large feet, which is a humorous observation for a boy to make—shows a lot about his personality. He’s curious, trying to figure her out. And of course he had never seen a girl like her before; she was from 70 years in the future.

It’s clear that I felt more drawn to Josh’s voice than Margaret’s, since I didn’t jot down any notes from Margaret’s point of view, but all in all the book was an entertaining read full of adventure and all the themes I love most—family, perseverance and good triumphing over the evil that may not be as evil as we had, at first, thought. Saving Lucas Biggs is a treat for adults and kids alike.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

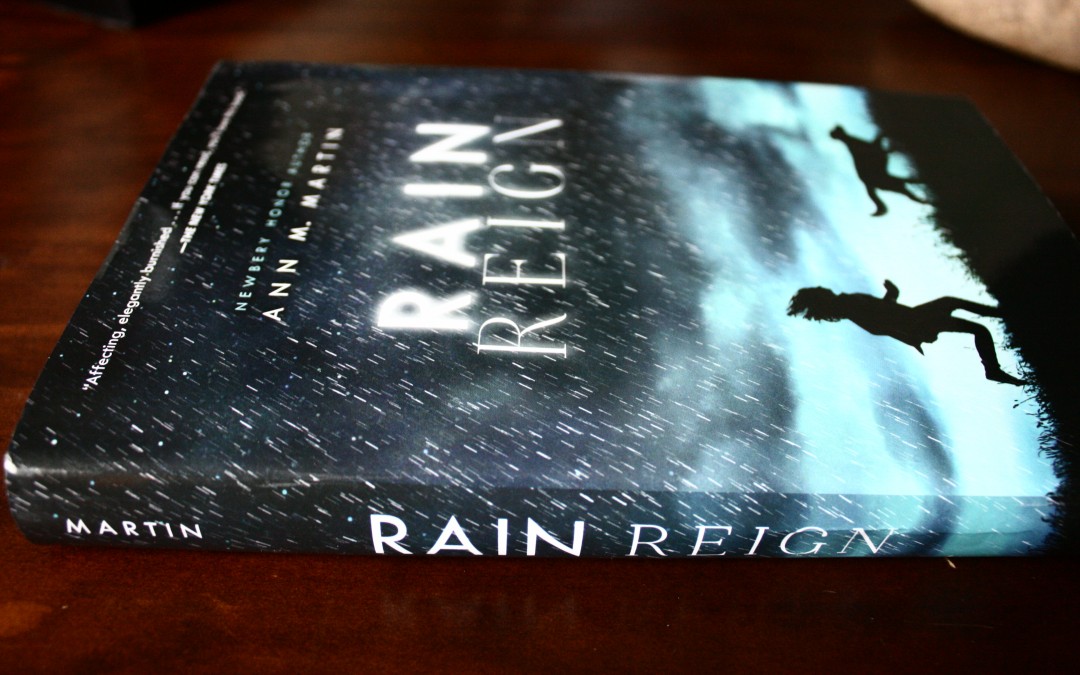

I’ve mentioned before that I run a book club where some women and I get together every month to talk about some books we’re reading. We take turns picking a book each other, and then we discuss any other books we’ve read that we’d recommend to each other, which means our book lists are miles long. A couple of months ago it was my turn to pick the monthly read, and I chose Rain Reign, by Ann M. Martin.

If you don’t recognize her name, Ann M. Martin is the author of The Babysitters Club series. I didn’t actually know this when I chose Rain Reign, because I hadn’t read The Babysitters Club books since I was about eight, but I like to google authors to see what I can find out about their inspiration for writing particular books, and that’s when I made the connection. This made me even more excited to read her book.

Let me just tell you, Rain Reign was one of the best middle grade books I’ve read in a long time, and I read a whole lot of them. The emotions, the situations, the innocence, the lessons, the voice, every part of this book was so beautiful. The story follows Rose Howard, who is a little girl with Asperger’s. Her teachers and her father don’t always understand her, but she has an uncle who loves her for who she is. She also has a dog named Rain. But then a major storm hits her town, and Rain goes missing, and the rest of the story is about her quest to find her dog that is really a quest to find herself and the truth about her mother and what it means to be a family. I still get chills talking about this book. It was so well written, so lovable, so charming—one of those books that grabs hold of you and won’t let go. Readers will not forget Rose or her story.

What I loved most about Rain Reign was that it was told from the perspective of Rose. Martin captured so eloquently the voice of a kid with Asperger’s, and I believe this book will not only help other kids understand that the kids with Asperger’s are not weirdos but ordinary people who see the world differently, but it will also help Asperger’s kids feel like they have a voice, that they are understood, that they are not expected to be someone different. What a great contribution to the world of children’s literature.

But lest you think this is just a story about a girl with Asperger’s, I must make it clear: this is a story about a girl and her dog. The story about a girl with Asperger’s takes a backseat to the story of Rain and Rose.

Martin skillfully characterized Rose within the first few pages, as Rose got straight to the point:

“I like homonyms a lot. And I like words. Rules and numbers too. Here is the order in which I like these things;

“1. Words (especially homonyms)

“2. Rules

“3. Numbers (especially prime numbers)

This is a perfect way to show how a kid with Asperger’s would have listed something out, because they are very precise and matter-of-fact.

Here’s another great passage:

“I’m going to tell you a story. It’s a true story, which makes it a piece of nonfiction.

“This is how you tell a story: First you introduce the main character. I’m writing this story about me, so I am the main character.”

So much voice contained in this short passage. It’s as if Rose is just reciting facts, which is what Asperger’s kids love to do.

Martin also deftly showed how Rose was obsessed with details, another characteristic of Asperger’s kids. Talking about her teacher’s helper, Rose says this:

“She sits in an adult-size chair next to my fifth-grade see chair and rests her hand on my arm when I blurt something out int he middle of math. Or, if I whap myself in the head and start to cry, she’ll say, ‘Rose, do you need to step into the hall for a moment?’”

It’s such an innocent observation—Rose doesn’t realize there’s anything unusual about having a helper in the classroom. I just love this innocence.

In other places, Rose used precise numbers to communicate details:

“Down the road, 0.7 miles from my house is the J&R Garage, where my father sometimes works as a mechanic, and 0.1 miles farther along is a bar called The Luck of the Irish, where my father goes after work. There is nothing between my house and the J&R Garage except trees and the road. (Tell me some things about your neighborhood.)”

“Uncle Weldon lives 3.4 miles away on the other side of Hatford.”

She’s practicing normal conversation, which is hard for her, but it’s easy to see that her conversation is anything but normal, because how many kids would know precisely how far something is from their house?

Rose doesn’t show much emotion but only communicates information (later in the book, we know of her emotion by the way she recites prime numbers during the overwhelming scenes. I thought that was a fantastic way to show readers that Rose is overwhelmed, because she falls back to her safe place. I didn’t want to share examples here, because there would be spoilers.). I also love that in the simple sentence about Uncle Weldon we not only get information about how far Uncle Weldon lives from her and her father, but we also get an idea of how large the town is.

Martin also utilized humor in some of Rose’s observations, like this one:

“Now he’s supposed to go to Hatford Elementary on the third Friday of every month at 3:45 p.m. To discuss me. This is what he said when he read that: ‘I don’t have time for meetings. This is way too much trouble, Rose. Why do you do these things?’ He said that at 3:48 p.m. on a Friday when there was no work for him at the J & R Garage.”

Rose has just gotten some notes sent home, saying that the principal and Rose’s teacher would like to have some regular meetings with her father to discuss her progress. She delivers her observation with such innocence and shows us many things: her father’s refusal to understand the way she is, her teachers’ concern over her, and how well she knows and observes her father’s activities.

Rose knows her dog just as precisely, too:

“Rain’s back is 18 inches long. From the tip of her nose to the tip of her tail she’s 34 inches long.”

This will help her later, when Rain is lost in the middle of a storm and Rose must call all the nearby shelters to see if they’ve found her.

Rose lets her reader understand the trouble with her father, with small mentions of hard eyes and annoyance, even though she can’t really tell what they mean. Here she is talking about how to know when she and Rain should stay away from her father:

“Rain is smart. She never goes near my father right away. She stands in the doorway to my bedroom while we wait to see whether my father will say, ‘What’s for supper?’ If he says, ‘What’s for supper’ then it’s safe for me to serve him and for Rain to sit by the table while we eat. She can stare at us and put her paws in our laps wanting food until I see my father’s eyes get black and hard and that’s the signal that Rain should go back to my bedroom.”

It’s clear that Rose is a very observant child, even though she can’t interpret the looks on people’s faces or, necessarily, the tone of their voices. But she gathers all the information and keeps it for herself, analyzing it in a very non-emotional manner.

Here she tells us a little about her diagnosis:

“I hear lots of things I’m not supposed to hear, and lots of things nobody else is able to hear, because my hearing is very acute, which is a part of my diagnosis of high-functioning autism. The clicks our refrigerator makes bother me, and so does the humming sound that comes form Mrs. Kushel’s laptop computer.”

“I hear clicks and humming and whispers. And conversations in the psychologist’s offie when the door is almost closed.”

Throughout the book, we are peeling back the layers of Rose. She doesn’t give us all the information up front, but they come out eventually. It’s one of the best things about the book.

After Rain is lost, Rose repeats the story as much as she can:

“This is because my father let Rain outside without her collar during a superstorm.”

Her repeating is a sign that she is upset, that she is still trying to come to terms with the loss of her dog. It was endearing.

Here’s the closest we get to her emotions, which she says after Rain gets lost:

“The afternoons are long. They seem to be full of empty space—space between looking through the box and starting my homework, space between finishing my homework and starting dinner. I don’t know what to do with the space. Rain used to fill it.

“How do you fill empty space?”

It was so sad, such great commentary on how it feels like when something goes missing from your life, delivered in such an innocent way. She feels very sad, but she just feels it as empty space.

This was one of the most beautiful passages in the book, showing, once more, the sorrow Rain feels at losing her dog:

“When I am at home alone I study my list of homonyms. I look through my mother’s box.

“That is all.

“There is an ache inside of me, a pain.

“Is this what bravery feels like? Or loneliness?

“Maybe this is an ache of sadness.”

As soon as I finished this book, I had to pick it back up and read it again to my 6-year-old, who is a dog lover. He can’t get enough of it, and even after the second time through, neither can I. Rain Reign is a book that will remain in the hearts of its readers forever.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

Every time I got on Amazon, there was this book that kept coming up as a recommended item: Kenneth Oppel’s The Nest.

I’d been hearing good things about this book, because I read a lot of book reviews and try to stay up-to-date on the newest releases, particularly in middle grade literature, so I finally found some room in my schedule and decided to pick it up.

It’s a really short read, but it’s packed with quite a bit of stuff. The main character is a kid whose baby brother was born with some metabolic issues. The boy, whose name is Steve, suffers from mental illness—anxiety most notably—and the book raises some great questions about what’s normal and what’s not, which was probably my favorite facet of it.

The Nest is considered a psychological thriller, which is unusual in the middle grade genre, but I found it to be tastefully written, scary but not too scary, weird but not too weird, fantastical but not too fantastical. Oppel writes very darkly, which I tend to love.

The main conflict in the story is centered around Steve’s baby brother and all his problems since birth. Steve feels a little forgotten by his parents, and he feels conflict within himself, because he loves his baby brother but he also wishes his baby brother were different so that he would have his parents and his “before” life back.

Early on, it becomes clear that Steve deals with some kind of mental illness, demonstrated in this passage, where Steve is telling his parents about a dream where he conversed with a giant wasp:

“I didn’t want to talk anymore, because I saw the fear in their eyes, and that made me afraid. Someone told me once that if you worried you were crazy, it meant you couldn’t be crazy. Because crazy people apparently had no idea they were crazy; they thought it was normal, walking around naked and yodeling. As I’d told my dreams aloud, I knew how insane they sounded—but I also remembered everything from those dreams, and they seemed real.

“Dad took a breath and tried to sound casual. ‘Maybe you should talk about this with Dr. Brown.’

“‘You think I”m crazy again,’ I said, and this time I was crying.

“Mom squeezed me hard. ‘You were never crazy. You were anxious, like a lot of people, like a lot of kids, and you’re also imaginative and sensitive. And wonderful.’ She kissed the top of my head. ‘So wonderful.’

‘I felt tired suddenly, in her arms. ‘I’ll go talk to Dr. Brown,’ I sighed. ‘But I want you guys to get rid of the nest.’

So he has been to this doctor before, but he clearly doesn’t really want to go back—mostly because what he wants, at the heart of him, is to be “normal.” This is such a sad reality for children with anxiety. They worry that they’re crazy. They worry that something is terribly wrong with them.

Steve also washes his hands compulsively and has other quirks that speak of anxiety and other neuroses:

“On the drive in to school, I used to silently name the same landmarks so I wouldn’t have a bad day. I had a relaxation tape I liked to listen to in the car. At school I drank only from a certain water fountain, and I washed my hands between every class. I also had hand sanitizer with me, just in case. Pretty much every day I worried I might feel sick and throw up in the middle of the hallway in front of everyone, and then no one would be my friend anymore.”

What I found so endearing about Steve’s neuroses is that we don’t meet a whole lot of characters like him in middle grade literature, yet there are many children who suffer from anxiety and depression and other psychological issues. So Oppel’s bravery in writing a character like Steve helps all those kids with the same kind of quirks at least feel a little more normal (if normal is what they’d like to feel). At most, it helps them feel less alone in their everyday struggles.

In another passage, Steve lets the reader see his feelings about his parents’ preoccupation with his baby brother. He’s talking with his therapist, who just asked whether he missed his imaginary friend:

“‘Not really,’ I lied. It wasn’t so much Henry I missed; it was having someone like him, only real, to talk to. The perfect listener, the person who could help me sort things out.”

I found this so sad—his parents are practically consumed with making sure his baby brother has everything he needs that they sort of forget that Steve is dealing with some issues of his own. And because he doesn’t want to cause them more worry, he just doesn’t say anything about what’s going on inside his mind—or the reality that feels like it might be fragmenting.

One of my favorite passages was this one:

“Sometimes we really aren’t supposed to be the way we are. It’s not good for us. And people don’t like it. You’ve got to change. You’ve got to try harder and do deep breathing and maybe one day take pills and learn tricks so you can pretend to be more like other people. Normal people. But maybe Vanessa was right, and all those other people were broken too in their own ways. Maybe we all spent too much time pretending we weren’t.”

It was a profound thought from a kid. Steve begins his thought by saying that those who are different must try to change to fit in and make people happy, and then he twists it with a truth about humanity: that we are all broken in different ways and that we shouldn’t pretend we aren’t.

This passage alone makes the book worth reading for a kid who struggles with something like anxiety or depression or mental illnesses. I have a son who has been flagged for depression and anxiety. You can bet I’ll be sharing this story with him, because the truth that is laid out from the mind of another kid who shares some of his tendencies is life-changing. Sometimes we learn best from the people who are most like us, and Oppel has given us a character in Steve that can help teach kids that there is nothing wrong with them; they’re just a little different.

I’m so glad that people like Kenneth Oppel challenge the traditional world of middle grade books and write a story that empowers children who are different to embrace who they are.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

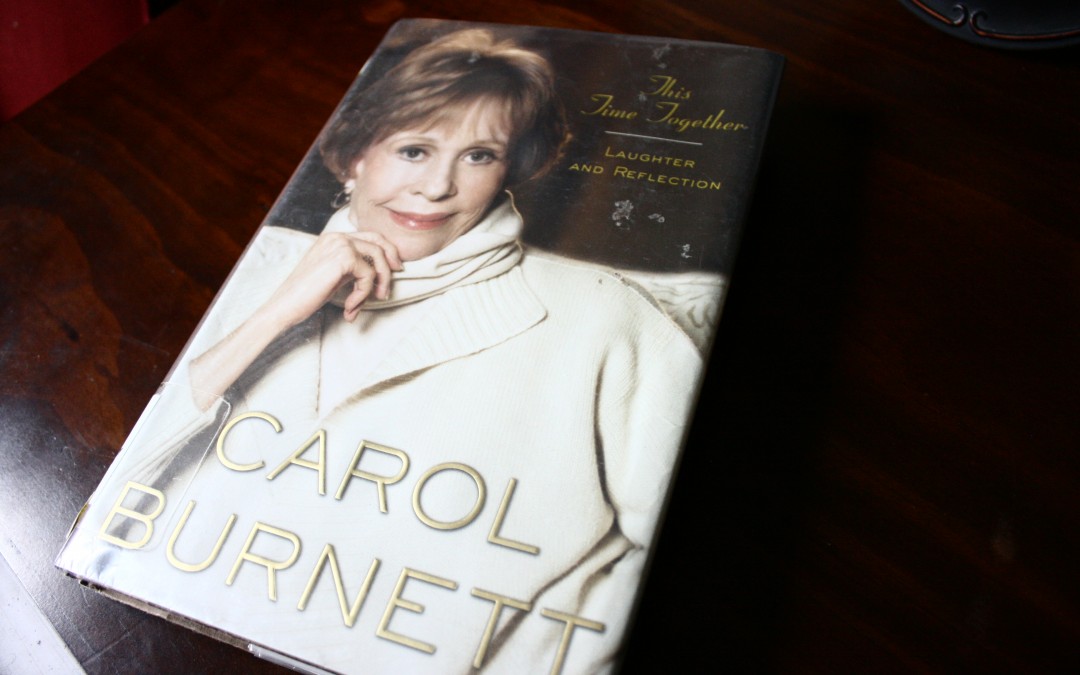

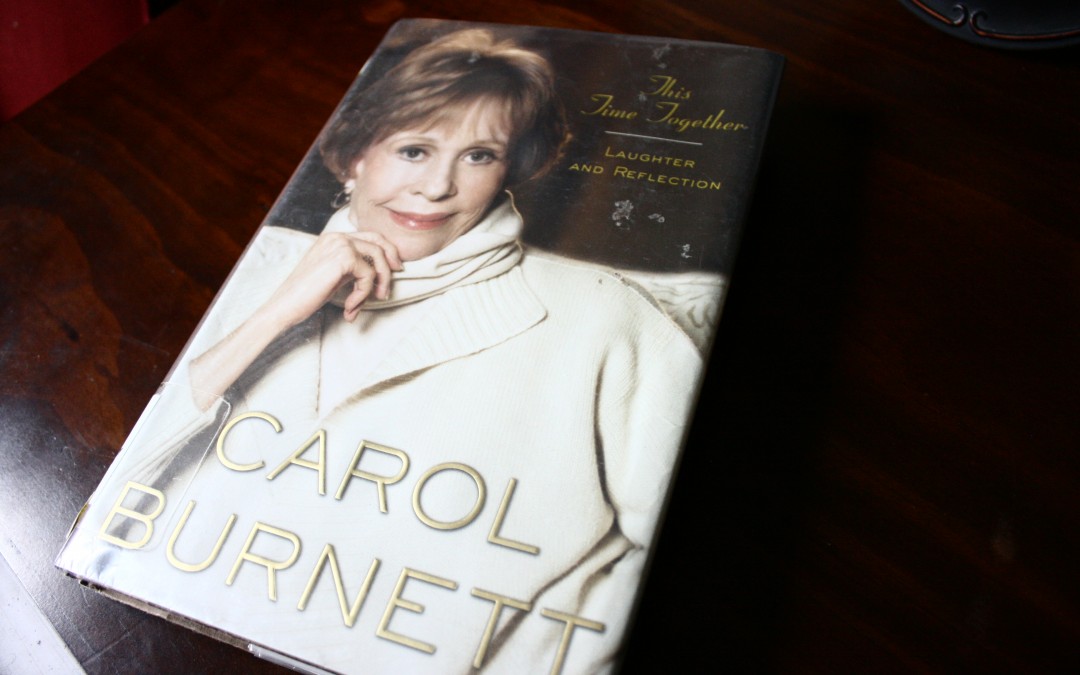

I’ve mentioned before that I really enjoy reading humor books. Some of my favorite humor writers include Erma Bombeck, Jim Gaffigan and Dave Barry. I recently read Carol Burnett’s memoir This Time Together, which wasn’t a straight-up humor book but was more a record of her rise to fame.

Burnett was part of a comedy troupe back before I was born, and she had a fascinating life. Sometimes, when comedians write their memoirs, they drop a lot of names or talk about things that lose readers if they’re not familiar with the shows they’re talking about, but even though Burnett was before my time, I found that This Time Together was not hard to follow.

This Time Together was the story of how Burnett got started in comedy and what it was like once she did. She and her kid sister grew up with their grandmother, and she launched out on her own when a wealthy friend gave her some money with the stipulation that when she made it famous, she would have to pay him back.

Burnett was a self-made woman, which I admire about her. It was fascinating to read the words of such a remarkable woman who made a name for herself during a time when women weren’t considered all that funny. She had some great stories about people she met along the way, her family, and other comedy legends who existed around that time.

One of the things I loved most about the book was that Burnett never made fun of another colleague but only told stories that they would have approved of, whether they were living or dead. I really respected that about her (not a lot of comedians or comediennes can stop themselves from the temptation of Making Fun of Other Colleagues). It couldn’t have been easy fighting for a place in a man’s world, and Burnett did it on her own merit—not only with integrity but also with class.

One of the lines I liked best in the book was this one:

“I have always believed there is something more to this world than just us. I remember being four years old and lying on the grass in the backyard in San Antonio looking up at that clouds. I don’t know how much time passed before I felt my body merging with the sky and the ground. I was everything, and everything was me.”

It shares a depth of Burnett that isn’t often seen when one is writing and performing humor; so I liked seeing another side of her personality—that wondering imagination of a child that resonates with the truth of humanity.

Burnett shares all sorts of funny stories, from something her daughter did at a restaurant, to her and Julie Andrews embarrassing themselves in front of Lady Bird Johnson—and what I loved about her humor was that it was humor from real life. There’s so much humor around us if we have on the right kind of eyes. Burnett draws that out. It was clear that Burnett finds humor in her everyday experiences—not by making fun of other people but by seeing the irony and the satire in her own life—which helps readers do the same in their own lives.

Interspersed with the humorous stories, Burnett sprinkled in serious parts that made me cry. It was by turns funny and emotional. She ended the book on a serious note, with a story about her daughter, Carrie, who had introduced the plan to turn Burnett’s first memoir into a play. The memoir was written about Burnett’s mother and father and her grandmother. Burnett and her daughter worked on it together, but in the middle of the project, Carrie was diagnosed with lung cancer and died before the play, which ended up winning a Tony Award, even debuted. The last section, written in such a raw way, made me cry, of course (big feelings). Carol, faced with finishing the project without her daughter, did not even want to get out of bed, she said, but then her husband told her she owed it to her daughter to finish the play and make sure it got produced. And so she did.

All in all, This Time Together was a great read, and I’ll probably go back and read all of Burnett’s other memoirs, because I enjoyed her style of writing. Her chapters were short, which makes a reader feel like they’re making significant progress even though they’ve only really read three pages. “Well, I finished a chapter,” I’d say, before the kids would come knocking on my door, trying to find me. “Now I feel accomplished.”

So you’ll laugh, you’ll feel inspired, and, if you’re like me, you’ll also cry—which is exactly what a book should make you do.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

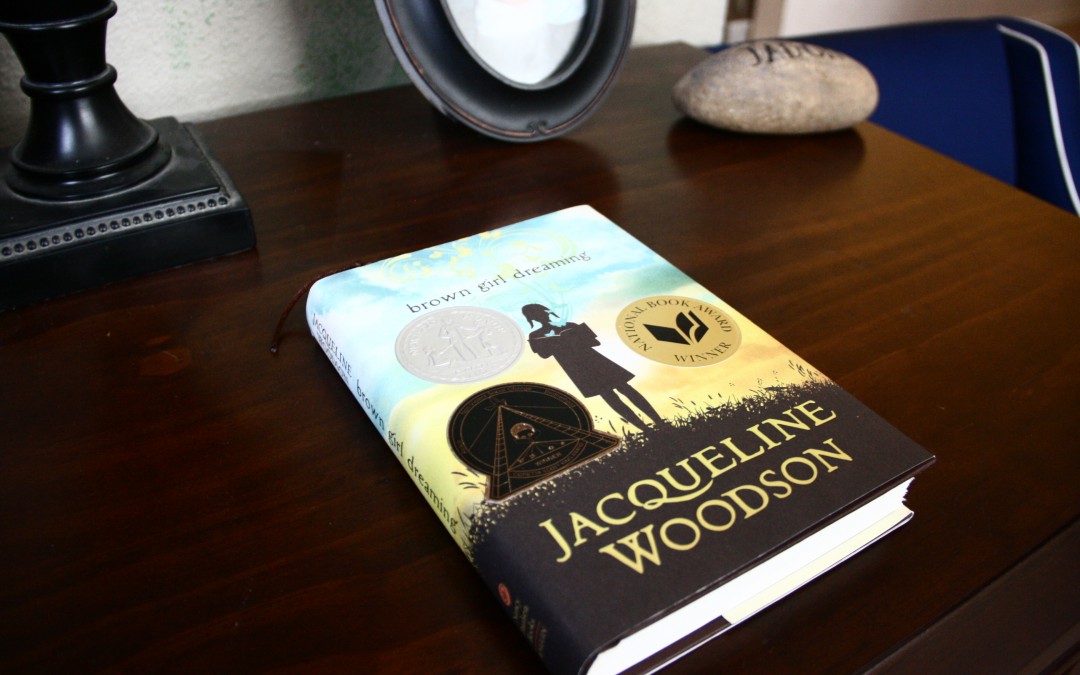

A memoir that recently captivated my heart was one written for the middle grade age. Brown Girl Dreaming, by Jacqueline Woodson, is a nonfiction memoir written in poetry, which I think is the best of both worlds. Woodson takes her readers through her birth and her growing-up years during the civil rights movement. She shares about her family background, all the setbacks she experienced as a little girl and when writing began to call to her.

I’m always fascinated by the lives of other people, especially when they’re writers, so I found myself completely lost in this story. I’d usually read it during our family’s Silent Reading Time, just before bed, and, every single night, I was surprised by the timer that says Silent Reading is over, which I call the mark of a great book.

Brown Girl Dreaming was a lovely read, and when I was trying to figure out why it was so lovely, I could only point to the language of it. Because the book is written in poetry, it is written in a beautiful language. Woodson took care with her words, and she fashioned them into just the right sort of combination so that they would not move through a mind but would rest in a heart.

Take her explanation of where she was born:

“I am born in Ohio but

the stories of South Carolina already run

like rivers

through my veins.”

The passage has great imagery, indicating that we are born into a family, but our history flows with many different places.

Woodson visited family themes frequently in Brown Girl Dreaming. Here she is speaking about some pictures she sorted through when she was just a girl.

“Look closely. There I am

in the furrow of Jack’s brow,

in the slyness of Alicia’s smile,

in the bend of Grace’s hand…

“There I am…

beginning.”

This resonated so deeply with me, because I enjoy looking at photos and trying to see the pieces in my family that I find in myself or in my boys. The passage speaks of heritage and existence.

Woodson was born in an important time, when black people were fighting for their rights. In one passage she says:

“I do not know if these hands will become

Malcolm’s—raised and fisted

or Martin’s—open and asking

or James’s—curled around a pen

I do not know if these hands will be

Rosa’s

or Ruby’s

gentle gloved

and fiercely folded

calmly in a lap,

on a desk,

around a book,

ready

to change the world…”

I find this a passage full of wonder and hope. She does not know what kind of life it will be for her. The image of the hands is a beautiful one—whose will she carry? It is the wondering of any child—will they be able to make a difference like all those who have come before?

Woodson showed off her grasp of beautiful language in several passages (too many to cite them all!):

Here, she is speaking of the death of an uncle:

“But the few words in my mother’s mouth

become the missing

after Odell dies—a different silence

than either of them has ever known.”

Here, she is documenting the difference between her grandmother and grandfather:

“And when we are called by our names

my grandmother

makes them all one

HopeDellJackie

but my grandfather

takes his sweet time, saying each

as if he has all day long

or a whole lifetime.”

Here, she is speaking of her mother and father trying to decide on her name:

“Name a girl Jack, my father said

and she can’t help but

grow up strong.

Raise her right, my father said,

and she’ll make that name her own.

Name a girl Jack

and people will look at her twice, my father said.

They compromised, of course, and named her Jacqueline.

And this passage, on what she finds when visiting her grandmother and grandfather:

“In downtown Greenville,

they painted over the WHITE ONLY signs,

except on the bathroom doors,

they didn’t use a lot of paint

so you can still see the words, right there

like a ghost standing in front

still keeping you out.”

When Woodson wrote about her father, who was not in her life for much of it, her words resonated deep within:

“So many years have passed since we last saw

our father, his absence

like a bubble in my older brother’s life,

that pops again and again

into a whole lot of tiny bubbles

of memory.”

Yes. I have known that bubble. The bubble never disappears, just forms into smaller bubbles that pop and make even more. So you’re still filled with the missing of him, but maybe it’s gotten a little easier. Or maybe just harder to ignore.

In another passage, Woodson shared what she used to do to bargain with the powers that be when she was a child:

“Each evening we wait for the first light

of the last fireflies, catch them in jars

then let them go again. As though we understand

their need for freedom.

as though our silent prayers to stay in Greenville

will be answered if

we do what we know is right.”

When you’re a child, you feel like everything you do is sort of a bargain. Do what you’re told, so you can get this one wish. Do the right thing, so your dad will come home. It was beautifully sad.

In this passage, Woodson’s grandmother has just admonished her grandchildren for not liking the neighbor girls because they get to play on a swings longer than Woodson and her siblings do. Her grandmother tells them their “hearts are bigger than that.”

“But our hearts aren’t bigger than that.

Our hearts are tiny and mad.

If our hearts were hands, they’d hit.

If our hearts were feet, they’d surely kick somebody!”

I laughed a little at this, because it’s such an accurate representation for what a kid feels in a fit of jealousy.

Again, her language in description showed a great mastery of metaphor and mechanics:

“Deep winter and the night air is cold. So still,

it feels like the world goes on forever in the darkness

until you look up and the earth stops

in a ceiling of stars.”

“You don’t need words

on a night like this. Just the warmth

of your grandfather’s arm. Just the silent promise

that the world as we know it

will always be here.”

“The page looks like the day—wrinkled and empty

no longer promising anyone

anything.”

“Darkness like a cape that we wear for hours, curled into it

and back to sleep.”

Woodson also shared about her struggles with reading and writing. She found it easier to tell stories than write them down. She also preferred reading books everyone considered beneath her level to the ones with a whole lot of pages and not many pictures. But a book with pictures was the first time she saw a black child depicted in the pages—and that made her believe that she could do what she felt was in her heart to do—write.

She tells of it in this passage:

“If someone had taken

that book out of my hand

said, You’re too old for this

maybe

I’d never have believed

that someone who looked like me

could be in the pages of the book

that someone who looked like me

had a story.”

Her description of what happens with a story when she begins telling it was fantastic:

“It’s easier to make up stories

than it is to write them down. When I speak,

the words come pouring out of me. The story

wakes up and walks all over the room. Sits in a chair,

crosses one leg over the other, says,

Let me introduce myself. Then just starts going on and on.”

At one point, she speaks about being the younger sister of a brilliant girl. The teachers, she said, waited for her to be brilliant, too.

“Wait for me to stand

before class, easily reading words even high school

students stumble over. And they keep waiting.

and waiting

and waiting

and waiting

Until one day, they walk into the classroom,

almost call me Odel—then stop

remember that I am the other Woodson

and begin searching for brilliance

at another desk.”

At times, Woodson’s poetry showed the true nature of a child, as in this passage about how she asked her mother if she could wear her hair in an Afro, and her mother said no:

“Even though she says no to me,

my mom spends a lot of Saturday morning

in her bedroom mirror,

picking her own hair

into a huge black and beautiful dome.

which

is so completely one hundred percent unfair

but she says, This is the difference between

being a grown-up and being a child. When

she’s not looking, I stick my tongue out

at her.”

The last poem of the book sums up Woodson’s theme: that even if we feel like we’re a mistake, even if we don’t think we have much of value to offer the world, we were planned for a purpose, and we are made to make the world a different place:

“When there are many worlds

you can choose the one

you walk into each day.”

“When there are many worlds, love can wrap itself

around you, say, Don’t cry. Say, you are as good as anyone.

Say, Keep remembering me. And you know, even as the world explodes

around you—that you are loved…

“Each day a new world

Opens itself up to you. And all the worlds you are—

Ohio and Greenville

Woodson and Kirby

Gunnar’s child and Jack’s daughter

Jehovah’s Witness and nonbeliever

listener and writer

Jackie and Jacqueline—

“gather into one world

“called You

“where you decide

“what each world

and each story

and each ending

will finally be.”

What a fantastic way to end a book for kids who are wondering if they really do have worth in this adult world.

I believe this is an important piece of literature in the children’s book world, because Woodson was a woman who grew up during an important time in history that children today will only read about in their history books. But she writes about that time with such honesty and emotion that her readers will not be able to pass over it as “just something that happened in history,” but will remember it was something that happened to actual people. When considering history, it’s easy to feel that distance from the tragedies that took place. But Woodson brings those tragedies front and center, in a gentle way. We need more literature like this in the middle grade genre, and I’m so thankful that Woodson so bravely told her story.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

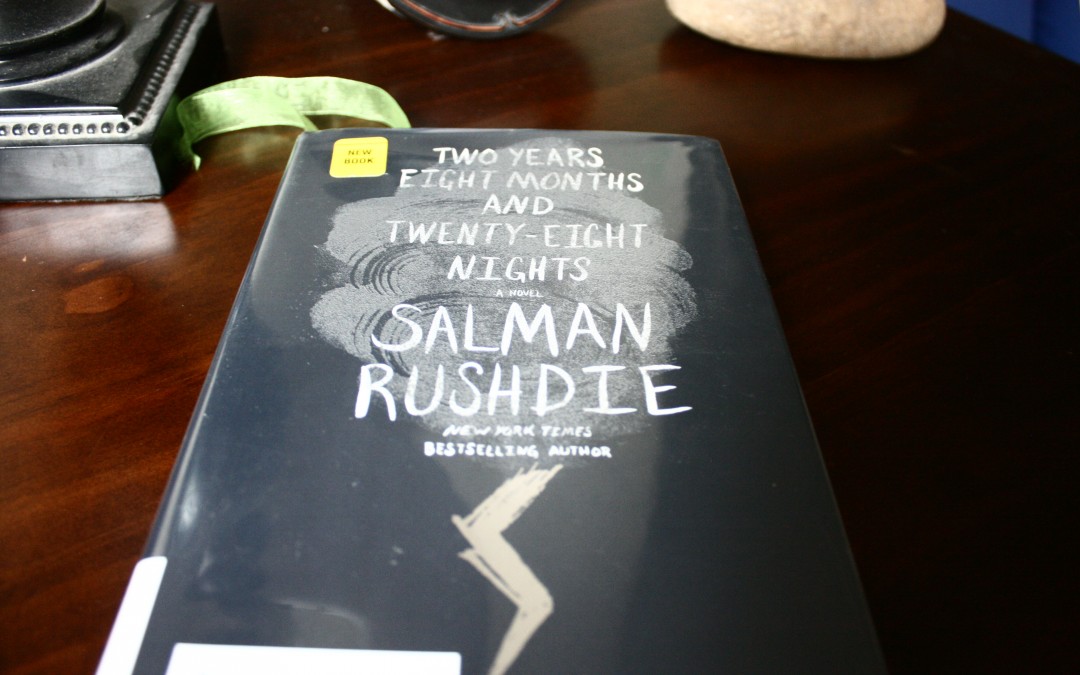

I’m really surprised that I’ve never read Salman Rushdie before, but I picked up his most recent book, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights because it was on the express shelf at my library. I actually picked it up by accident, because, for some reason, I read the author’s name as Sherman Alexie, who is the author of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, and I thought he’d come out with a new book. I know. I call it Mom Brain.

But I’m glad I accidentally picked up this book. Once I got started with it, I could hardly put it down.

It’s hard to describe Rushdie’s style. He is a masterful storyteller. Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights tells the story of the djinn, which were like genies in Arabian and Islamic mythology. But the way that Rushdie told this story was like a history of sorts. You had the feeling that you were reading a true account of how djinnis tried once to overtake the world and were defeated. Not only that, but the characters were weird and interesting and had distinct personalities of their own. It was a fantastically written book, although I will admit this one took me much longer to read than most books, probably because Rushdie has a very intellectual style, which I really enjoy but which takes longer to process and fully digest.

Throughout his pages, Rushdie had passages that contributed to the work seeming like a true story. Take this one, for example:

“How treacherous history is! Half-truths, ignorance, deceptions, false trails, errors, and lies, and buried somewhere in between all of that, the truth, in which it is easy to lose faith, of which it is consequently easy to say, it’s a chimera, there’s no such thing, everything is relative, one man’s absolute belief is another man’s fairy tale; but about which we insist, we insist most emphatically, that it is too important an idea to give up to the relativity merchants.”

One of my favorite elements to Rushdie’s book was the way he interspersed it with social commentary.

“History is unkind to those it abandons, and can be equally unkind to those who make it.”

“What happens to our mind befalls our body also. The condition of the body is also the state of the mind.”

“It was the resilience in human beings that represented their best chance of survival, their ability to look the unimaginable, the unconscionable, the unprecedented in the eye.”

Not only did he give us social commentary that felt like a truth, but he also made it poetic, and the poetry made it ever more profound. Here he is, commenting on the religious world and on history:

“Perhaps, as a godly man, he would not have been delighted by the place history gave him, for it is a strange fate for a believer to become the inspiration of ideas that have no need for belief, and a stranger fate still for a man’s philosophy to be victorious beyond the frontiers of his own world but vanquished within those borders…”

“The garden was the outward expression of inner truth, the place where the dreams of our childhoods collided with the archetypes of our cultures, and created beauty.”

His work was abundant with beautiful imagery:

“Their childhoods slipped into the water and were lost, the piers built of memories on which they once ate candy and pizza, the boardwalks of desire under which they hid from the summer sun and kissed their first lips.”

“But when the light returned it felt different. This was a white light they had not seen before, harsh as an interrogator’s lamp, casting now shadows, merciless leaving no place to hide. Beware, the light seemed to say, for I come to burn and judge.”

“Above the gates of the estate a live wire swung dangerously, with death at its tip.”

“The tree roots standing up in the black mud like arms of drowning men.”

Rushdie’s characters in Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights, were strange yet charming, with personalities that one would not soon forget (reminiscent of the characters in Daniel Handler’s We Are Pirates). Rushdie is a master at giving his characters distinctive voices, though the book was written in third-person perspective. I had a grand time studying his methods.

Here’s one of his characters who runs an apartment complex in a bad part of town:

“Gun crazy was normal to her, shooting-kids-at-school or putting-on-a-Joker-mask-and-mowing—people-down-in-a-mall or just plain murdering-your-mom-at-breakfast crazy, Second Amendment crazy, that was just the everyday crazy that kept going down and there was nothing you could do about it if you loved freedom; and she understood knife crazy from her you’re days in the Bronx, and the knockout-game type of crazy that persuaded young black kids it was cool to punch Jews in the face. She could comprehend drug crazy and politician crazy and Westboro Baptist Church crazy and Trump crazy because those things, they were the America way, but this new crazy was different. It felt 9/11 crazy: foreign, evil. The devil was on the loose, Sister said, loudly and often. The devil was at work.”

This was another passage that not only expertly characterized but also lent to the book a historic feel—with the references to a guy putting on a Joker mask and Westboro and even Trump. These are references that don’t feel contrived and, also, don’t date the book as some might fear (sometimes that keeps writers from putting in cultural references). It’s likely that these things—Trump, Westboro Baptist Church and the Joker mask killer—will be remembered for a very long time.

Here’s Rushdie writing about another character, Blue Yasmeen, in one of the most brilliant characterization passages in the book:

“Blue Yasmeen’s hair wasn’t blue, it was orange, and her name wasn’t Yasmeen. Never mind. If she said blue was orange that was her right, and Yasmeen was her nom de guerre and yeah, she lived in the city as if it were a war zone because even though she had been born on 116th Street to a Columbia literature professor and his wife, she wanted to recognize that originally, before that, which was to say before fucking birth, she came from Beirut. She had shaved off her eyebrows and tatted new ones in their place, in jagged lightning-bolt shapes. Her body too was a tat zone. All the tattoos except the eyebrows were words, the usual ones, Love Imagine Yeezy Occupy, and she said of herself, unintentionally proving that there was more in her of Riverside Drive than Hamra Street, that she was intratextual as well as intrasexual, she lived between the words as well as the sexes. Blue Yasmeen had made a splash in the art world with her Guantanamo Bay installation, which was impressive if only for the powers of persuasion required to make it happen at all: she somehow got that impenetrable facility to allow her to set a chair in a room with a video camera facing it, and linked that to a dummy sitting in a Chelsea art gallery, so that when inmates sat in the Guantanamo chair room and told their stories their faces were projected onto the head of the Chelsea dummy and it was as if she had freed them and given them their voices, and yeah, the issue was freedom, motherfuckers, freedom, she hated terrorism as much as anyone, but she hated miscarriages of justice too, and, FYI, just in case you were wondering, just in case you had her down as a religious-fanatic terrorist in waiting, she had no time for God, plus she was a pacifist and a vegan, so fuck you.”

There is so much to say about this passage. The repetition of the word “yeah” and all the cussing and even the tiny little references to things like, “she wanted to recognize that” and “FYI, just in case you were wondering,” gives the impression that Blue Yasmeen is speaking to us, even though a narrator is actually our go-between. It was fantastic prose.

One of my other favorite characterization passages was this one (because I’m a mom of six boys and, also, juvenile):

“He was waiting for the word from the Lightning Princess. Sometimes for a change he headed south to Calvary or Mount Zion cemeteries and blew the heads off stone lions in those locations also, and performed new changes, he could turn solid objects into smells now, one minute it was a bench, the next it was a fart, it was the accumulation of all the farts farted by old farts male and female sitting on that bench thinking about other old farts, now deceased, Macfart shall fart no more.”

I laughed so hard at this passage and even had to read it to my husband so I didn’t have to laugh alone. That one could take a book as serious and horrific as this one and infuse humor into it is astounding and the mark of a skilled author.

It wasn’t the only time Rushdie used humor in his pages, which I found endearing. Here’s another short humorous thought:

“Beware of the man (or jinni) of action when he finally seeks to better himself with thought. A little thinking is a dangerous thing.”

This book was a fantastic read; and if you’re still not convinced, I’ll close with two of my favorite passages, on the nature of love:

“At the beginning of all love there is a private treaty each of the lovers makes with himself or herself, an agreement to set aside what is wrong with the other for the sake of what is right. Love is spring after winter. It comes to heal life’s wounds, inflicted by the unloving cold. When that warmth is born in the heart the imperfections of the beloved are as nothing, less than nothing, and the secret treaty with oneself is easy to sign. The voice of doubt is stilled. Later, when love fades, the secret treaty looks like folly, but if so, it’s a necessary folly, born of lovers’ belief in beauty, which is to say, in the possibility of the impossible thing, true love.”

“‘Only with God,’ Ghazali replied. ‘That was and is my only lover, and he is and was more than enough.’”

You’ll get everything with Rushdie’s book: laughter, horror, entertainment, history, memorable characters, and, mostly, lovely language and a story you won’t ever forget.