by Rachel Toalson | Books

I discovered poet Mary Oliver last year around the time that her newest poetry book, Felicity, came out. I read poetry continuously, because I believe that poetry is the cornerstone for good writing; if you have a good grasp of poetry, you have a good grasp on language and diction and all the pacing needed for good writing. So I was delighted to discover Oliver and, quite immediately, fall in love with her poetry.

Oliver has been writing poetry since 1963, when she published her first poetry book at 28 years old. Her American Primitive collection won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984. Other books have garnered countless awards for their beauty and simplicity.

It’s plain to see why Oliver’s poetry is so celebrated. She has a singular style that provides a window into the natural world that is not only a lovely experience but also a transformative one. In many of Oliver’s poems, one could imagine her sitting beside a pond, enjoying nature, or walking her dog through a park or resting on a bench, watching the sky. She takes the most ordinary circumstances and makes them come alive. Her images are spectacular. Take this passage, from her poem, “Spring:”

“Even before the sun itself

hangs, dissattached, in the blue air,

I am touched everywhere

by its ocean of yellow waves.”

The picture she gives us is beautiful in its clarity, the rising of the sun like a yellow ocean.

Here’s a passage from her poem, “Wings:”

“But my bones knew something wonderful

about the darkness—

and they thrashed in their cords,

They fought, they wanted

to lie down in that silky mash

of the swamp, the sooner

to fly.”

What fantastic imagery. Oliver is telling us that there is something good in the dark—flying, being able to soar above the earth without any attachments—something we cannot find in the light. This is something only a body would know, not a brain, because the brain is afraid of the dark.

This passage from “The Kingfisher” tells us, again, the good (beauty) found in the bad (dying):

“I think this is

the prettiest world—so long as you don’t mind

a little dying, how could there be a day in your whole life

that doesn’t have its splash of happiness?”

It’s the daring challenge of nature: find a “splash of happiness” in every day of our lives. Oliver uses the natural world to remind us that even though the flowers pass away, we can still find the happiness of having watched them bloom.

In “The Deer,” Oliver theorizes about what happens to the body after death:

“When we die the body breaks open

like a river;

the old body goes on, climbing the hill.”

I found this image lovely, that we would break apart, back into the natural world, and our essence travels on, climbing a hill, still entombed in nature.

In “The Loon on Oak Head Pond,” Oliver showcases her ability to craft a beautiful turn of phrase:

“You come every afternoon, and wait to hear it.

You sit a long time, quiet, under the thick pines,

in the silence that follows.

As though it were your own twilight.

As though it were your own vanishing song.”

She is writing of someone she has observed, it seems, someone old, and the someone watches and waits in the silence of the afternoon, as if awaiting his own death.

Oliver explores more the question of death in “What Is it?”

“Of the transforming water,

and how could anyone believe

that anything in this world

is only what it appears to be—

that anything is ever final—

that anything, in spite of its absence,

ever dies

a perfect death?”

It’s clear that Oliver can hear the communication of the natural world; she hears the words it speaks about death and life and hope. She captures that perfectly in her words.

I loved her commentary on sorrow from “The Lilies Break Open Over the Dark Water:”

“But the lilies

are slippery and wild—they are

devoid of meaning, they are

simply doing,

from the deepest

spurs of their being,

what they are impelled to do

every summer.

And so, dear sorrow, are you.”

In “Snake,” Oliver echoes another great natural poet, Emily Dickinson, in writing about hope:

“There are so many stories,

more beautiful than answers.

I follow the snake down to the pond,

thick and musty he is

as circular as hope.”

Hope is circular. It never ends. I love that she took something–hope being forever–and put it in her own words, by watching a snake.

I enjoyed her musings in “Roses, Late Summer:”

“If I had another life

I would want to spend it all on some

unstinting happiness.

I would be a fox, or a tree

full of waving branches.

I wouldn’t mind being a rose

in a field full of roses.

Fear has not yet occurred to them, nor ambition.

Reason they have not yet thought of.

Neither do they ask how long they must be roses, and then what.

or any other foolish question.”

She is essentially saying that the ordinary human worries and wonderings do not occur to the natural world—and that gives them a peace and a beauty that we cannot achieve ourselves.

Here’s one more passage, from the poem “White Owl Flies Into and Out of the Field,” in which Oliver writes of death. I found it beautifully phrased:

“And then it rose, gracefully,

and flew back to the frozen marshes,

to lurk there,

like a little lighthouse,

in the blue shadows—

so I thought:

maybe death

isn’t darkness, after all,

but so much light

wrapping itself around us—

as soft as feathers—

that we are instantly weary

of looking, and looking, and shut our eyes,

not without amazement,

and let ourselves be carried,

as through the translucence of mica,

to the river

that is without the least dapple or shadow—

that is nothing but light—scalding, aortal light—

in which we are washed and washed

out of our bones.”

Mary Oliver’s poetry is transcendent and spiritual and beautiful, and I’ve since picked up many of her other books, to study a true master at work.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

I love it when I find phenomenal nonfiction picture books that tell the story of some amazing person who overcame obstacles and still achieved their dreams. We own a few of these, but recently I discovered more to add to the mix.

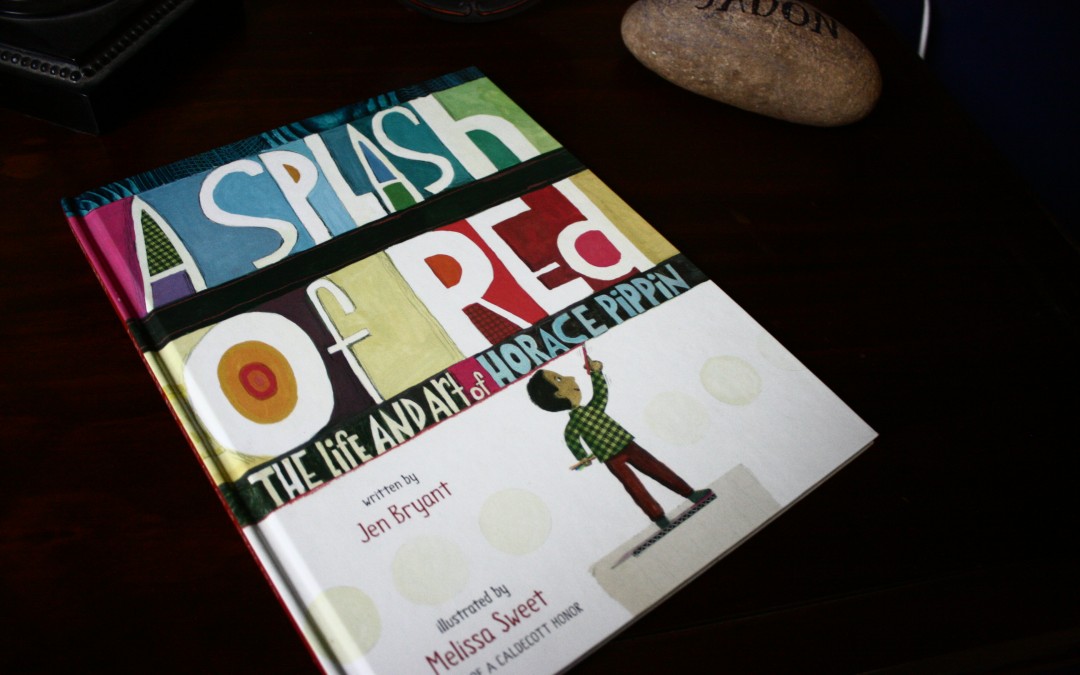

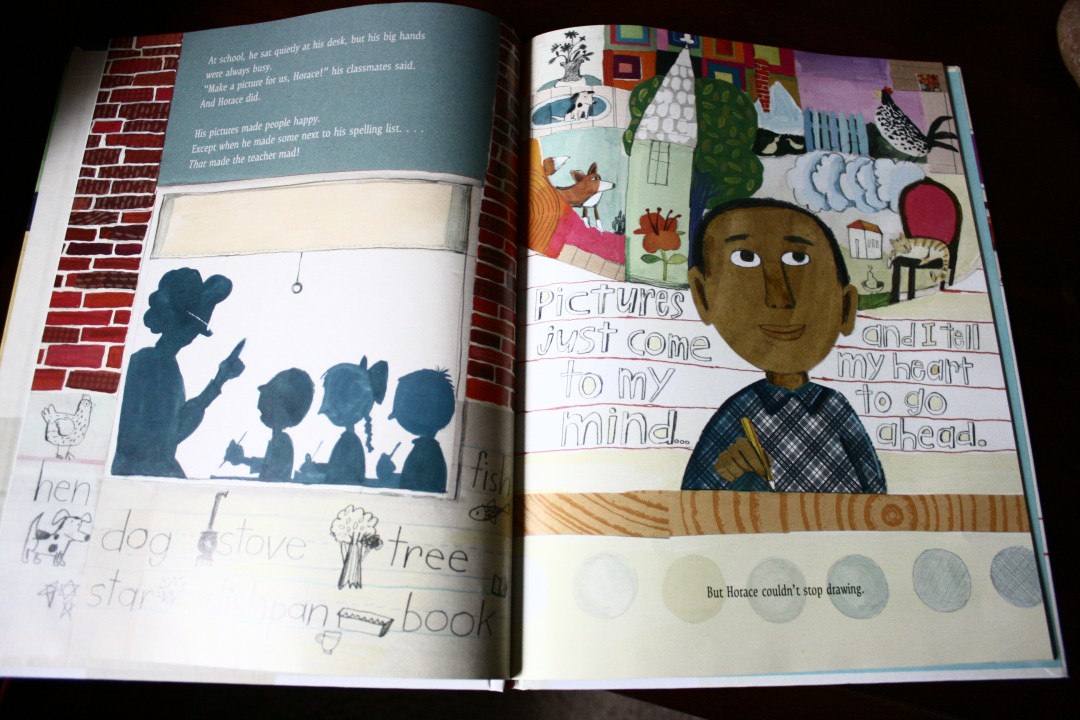

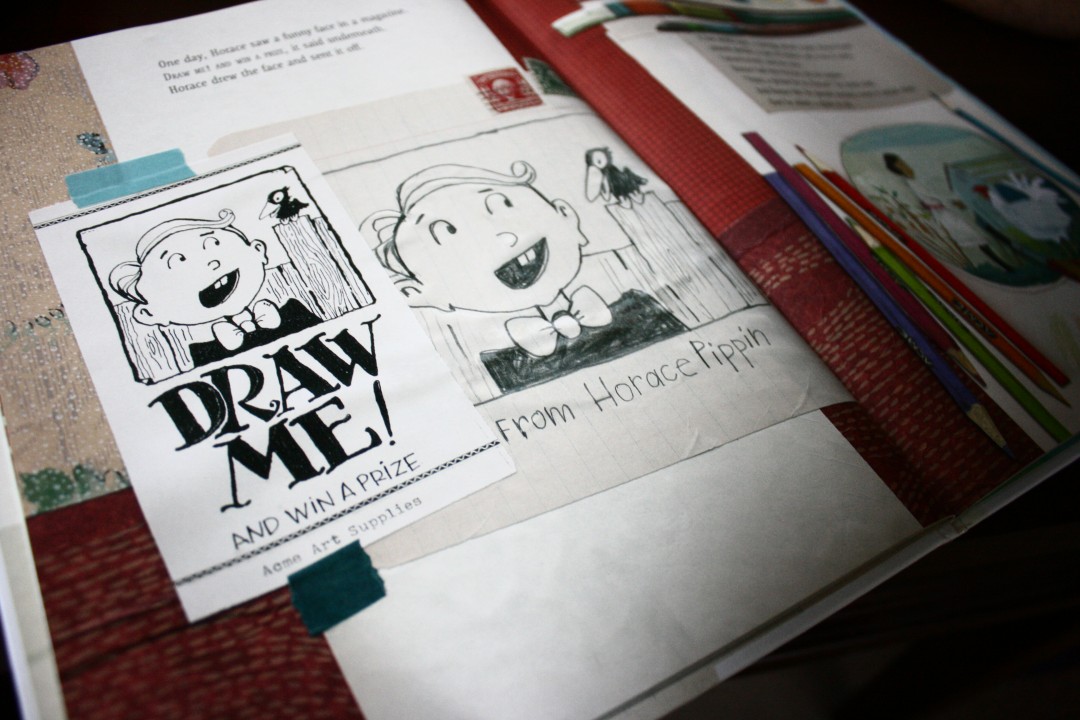

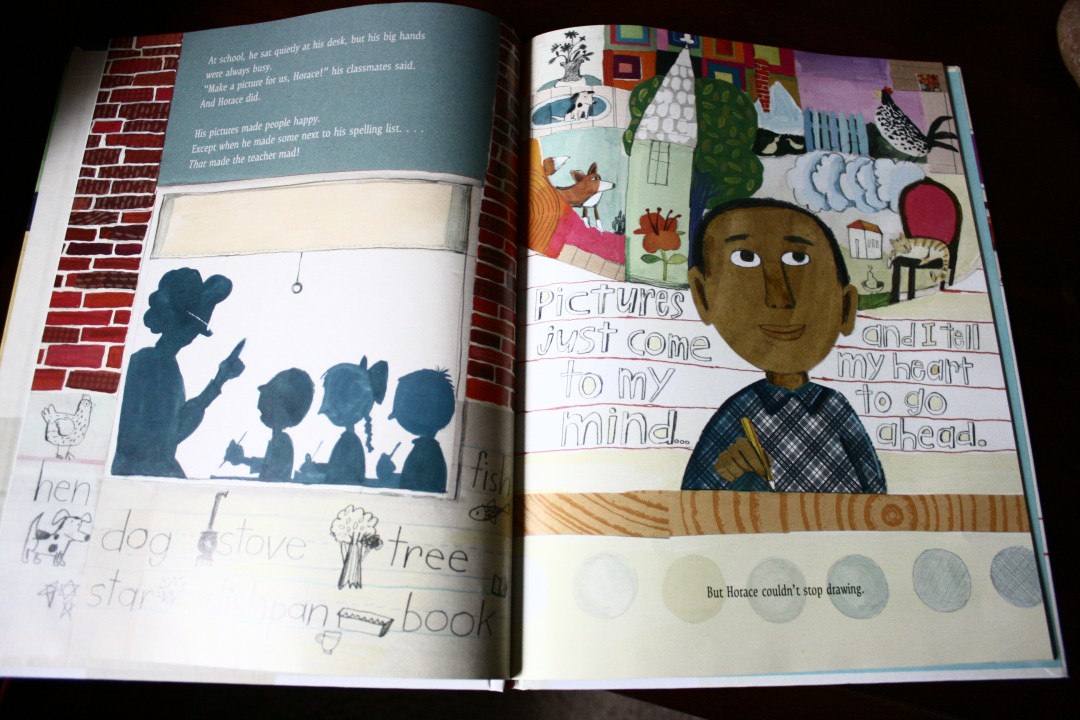

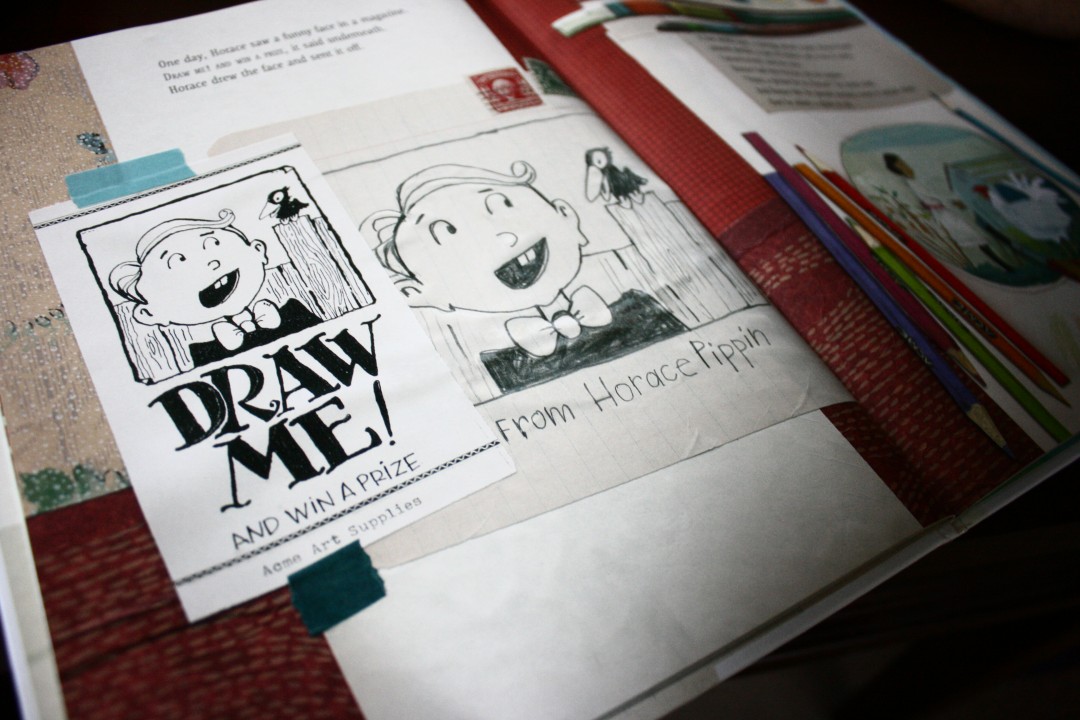

1. A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin, written by Jen Bryant and illustrated by Melissa Sweet.

This one was one of my favorites. Horace Pippin is a black American painter. He grew up painting, but he grew up poor and had limited resources he could use to pursue his passion. This book tells the story of how he got his first paint set: sending off to an old mail-order contest. It tells of Horace’s growing up and going off to war, and then it tells about how he was shot in his right arm and lost the ability to paint.

For a while, Horace did hard labor, after marrying a woman he met upon his return to the states. But the art would not leave him, and, eventually, he taught himself how to hold a brush with his right hand but use his left hand to guide his right hand’s painting.

It’s an incredible story of wonder and imagination and hope and overcoming all the odds. It’s inspiring for kids to not only read about people who overcame odds like a man who lost the use of a painting arm and still produced some of the greatest art we have in history today, but it’s also valuable for them to learn about people who overcome poverty to become who they dreamed they’d be. Horace Pippin was a great man whose story will surely live on in the hearts of the children who read about him.

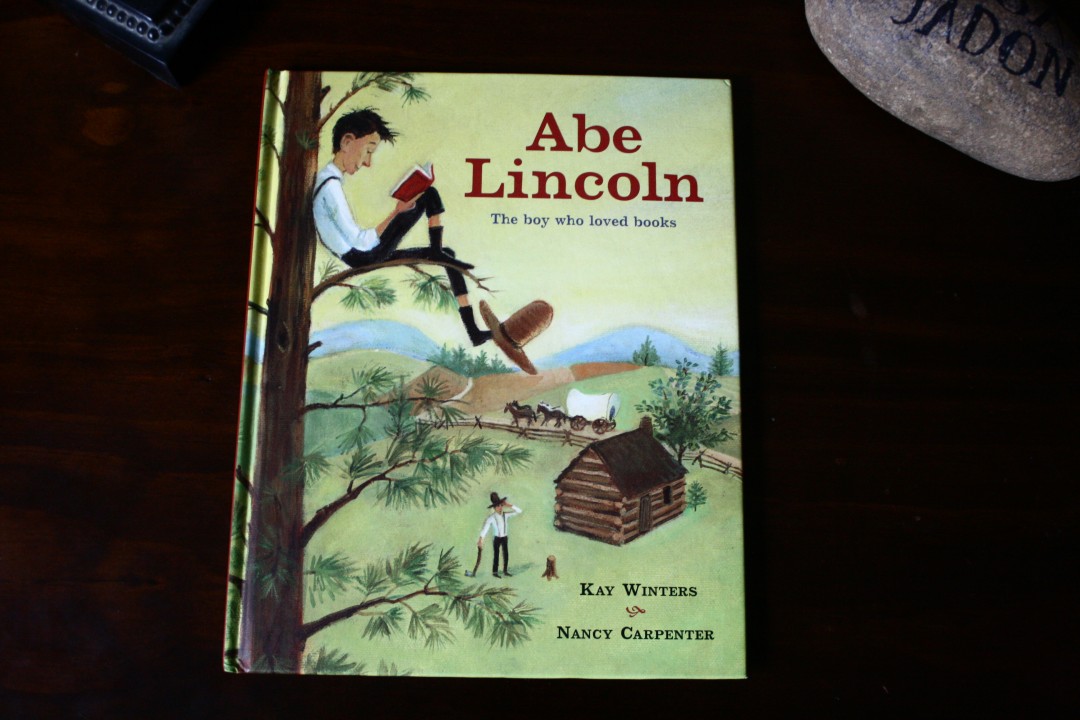

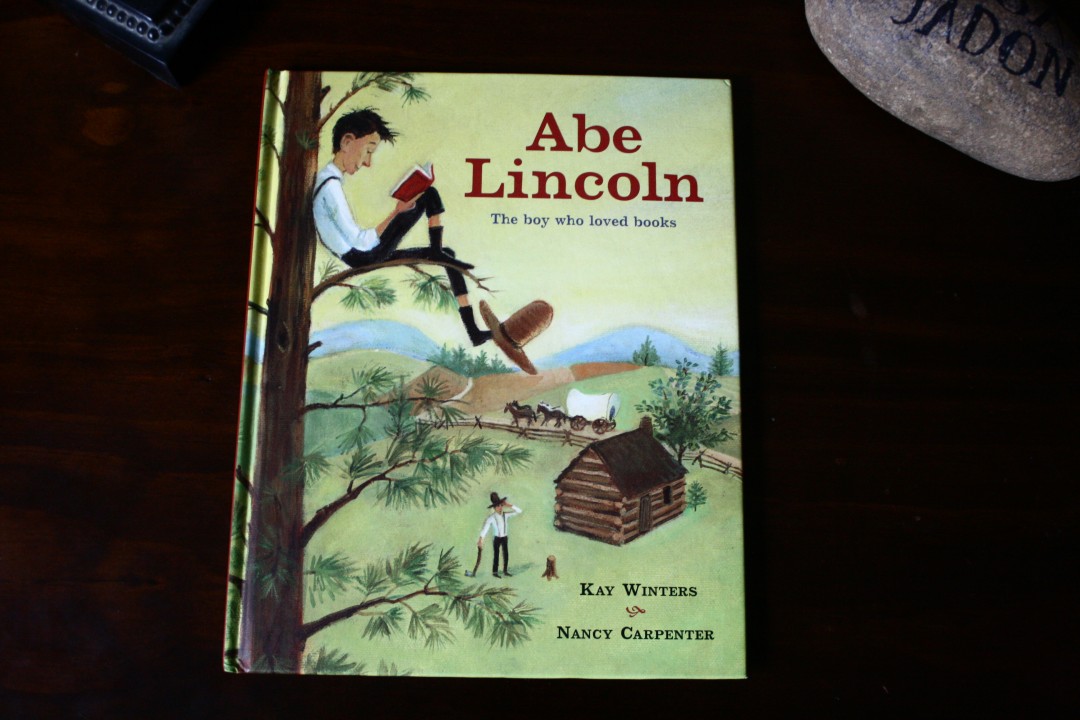

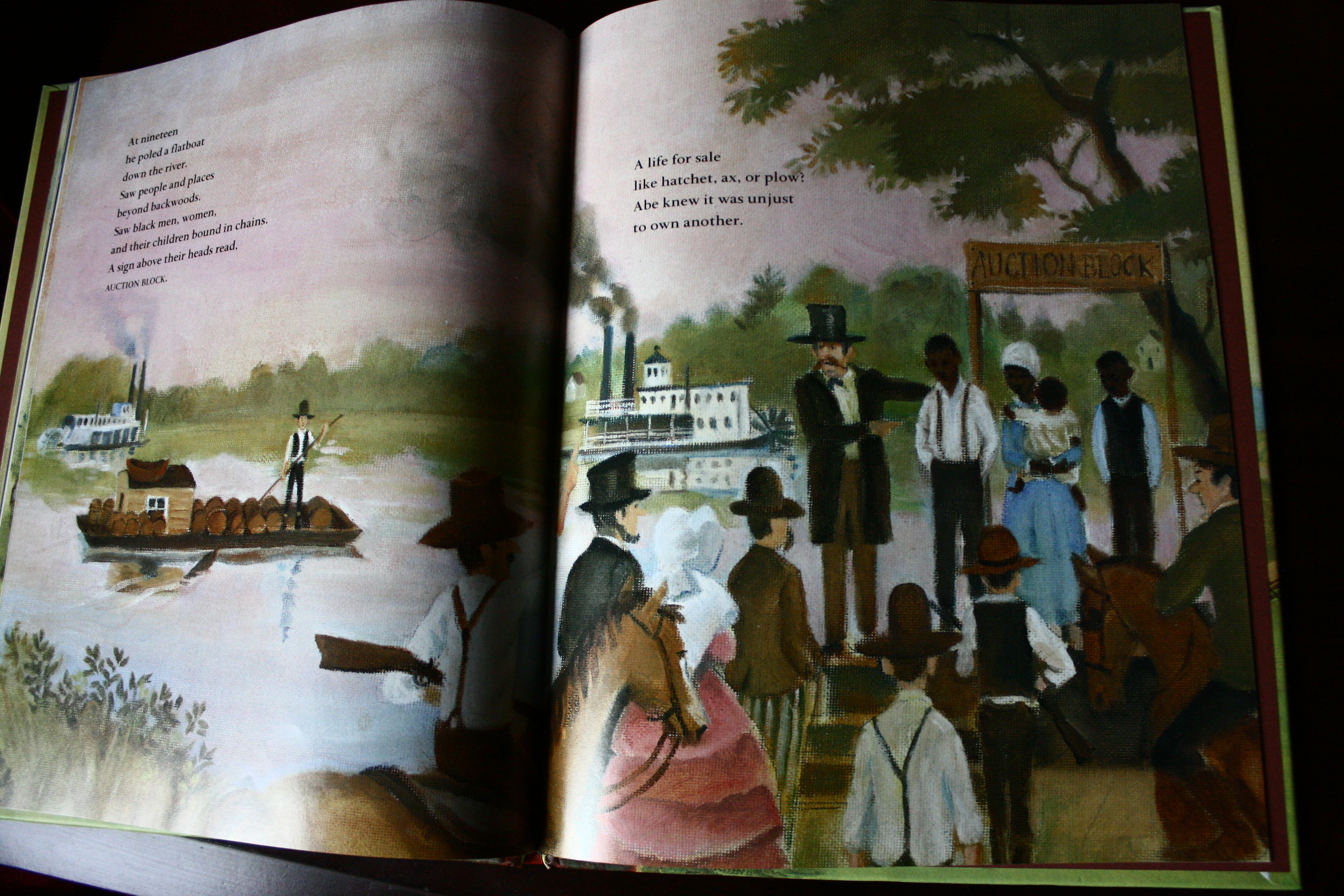

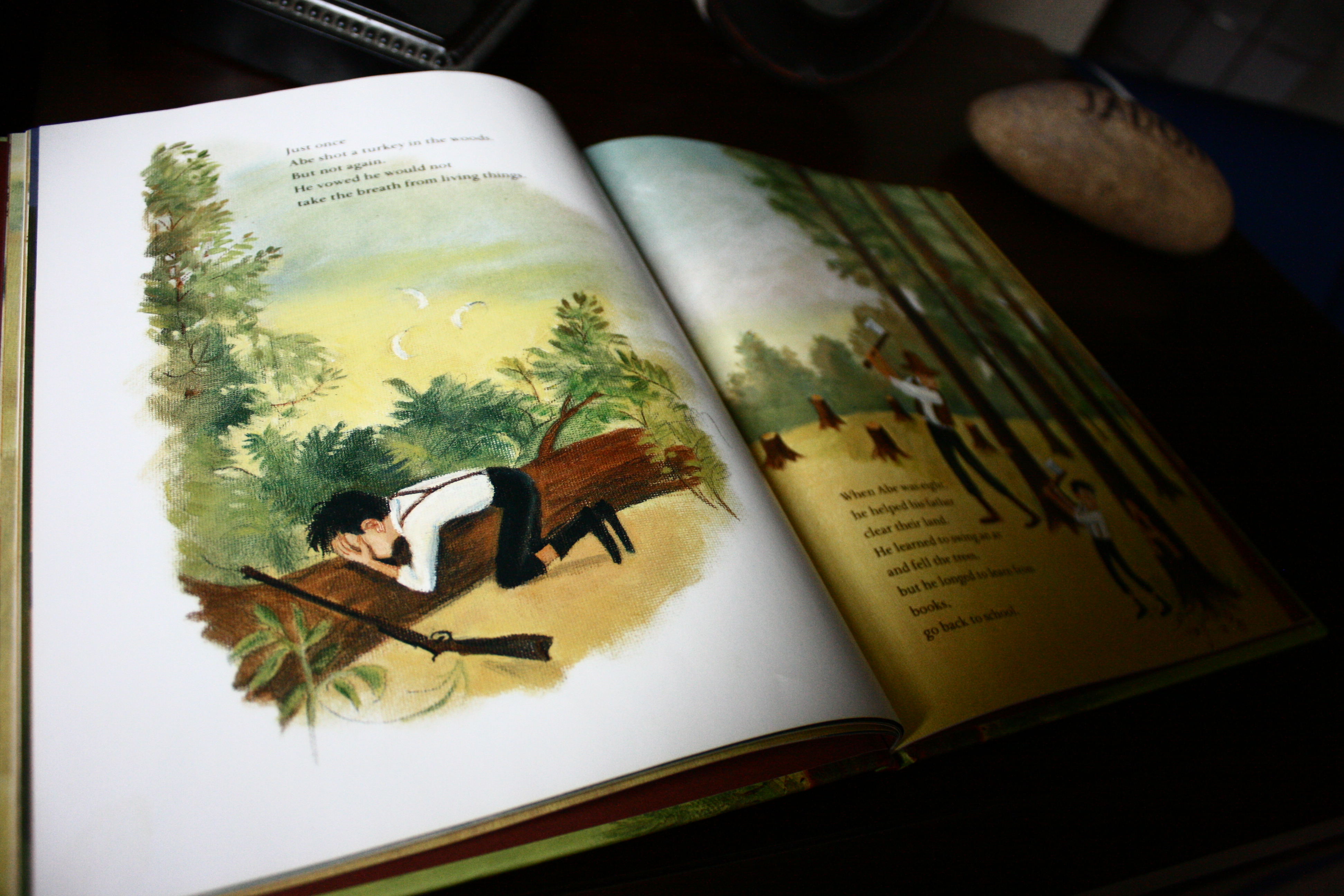

2. Abe Lincoln: The boy who loved books, by Kay Winters and Nancy Carpenter.

This is a book I got for my 9-year-old, who always has his nose stuck in a book, one Christmas. It tells the story of Abraham Lincoln, who started as a poor boy and became one of the most beloved presidents in American history. The story is told lyrically and beautifully, with references to books and the knowledge that books can give you threaded throughout. Lincoln’s peaceful and honest nature was also emphasized through a story about a fight with another man and another story about Lincoln chasing down a customer to give them the change they forgot to take at the end of a transaction.

My boys ask to hear this story all the time. It’s another inspiring read for children who wonder what they have to offer the world.

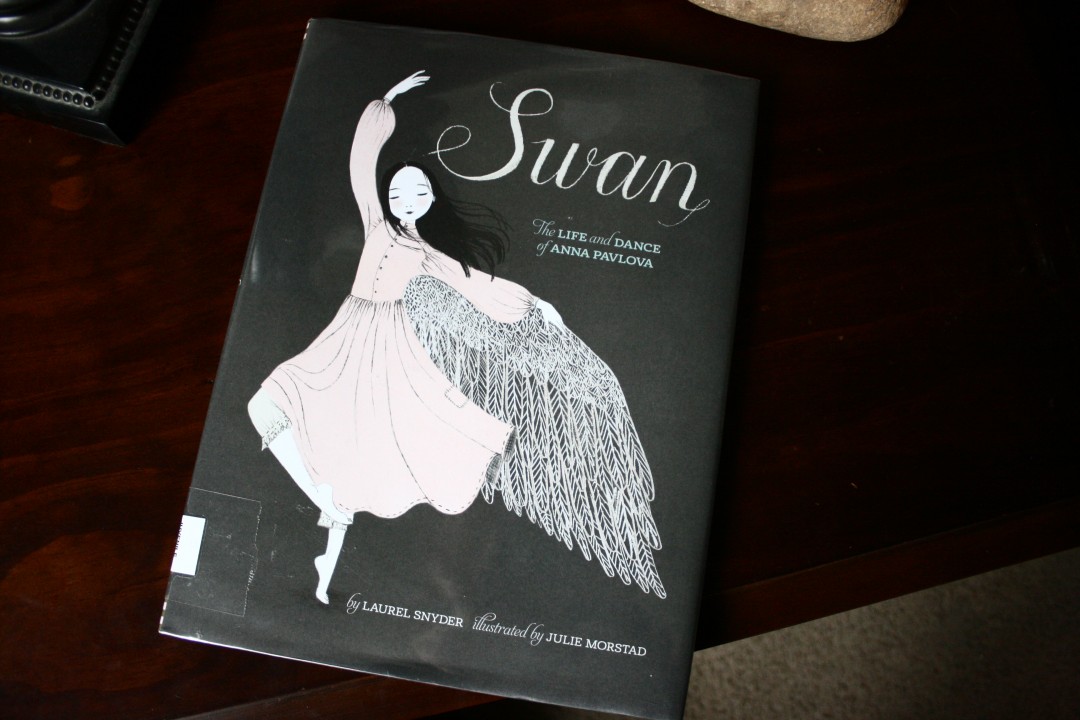

3. Swan: The Life and Dance of Anna Pavlova, written by Laurel Snyder and illustrated by Julie Morstad.

This is another nonfiction book that was written lyrically and with beautiful pictures. It captivated my boys, though it was a story about ballet. But Pavlova is another story of poverty-to-brilliance and overcoming overwhelming obstacles. The book tells of how Pavlova was, at first, not quite accepted as a true ballerina because she was too thin and she could not dance on her toes as she should. But Pavlova overcame those objections to become one of the most celebrated dancers in our history.

The book follows Pavlova from the time she was a little girl, hanging clothes on the laundry line for her mother, to when she danced her last dance and died. Kids will love this book not only for the gorgeous illustrations but also for the theme threaded throughout: that people may doubt you, but you have the last call on who you become.

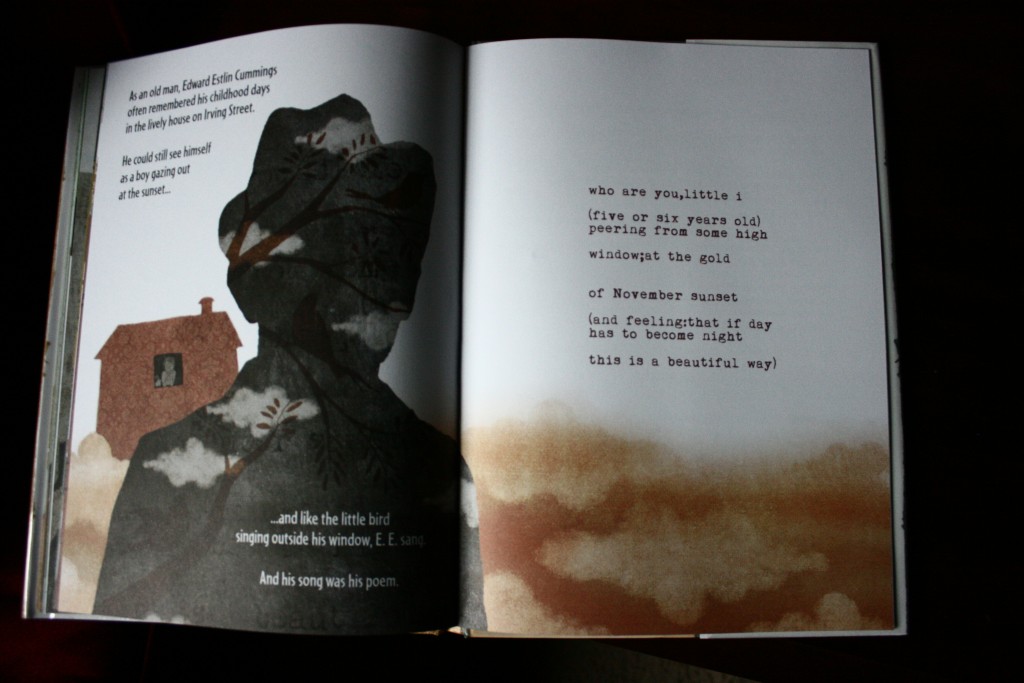

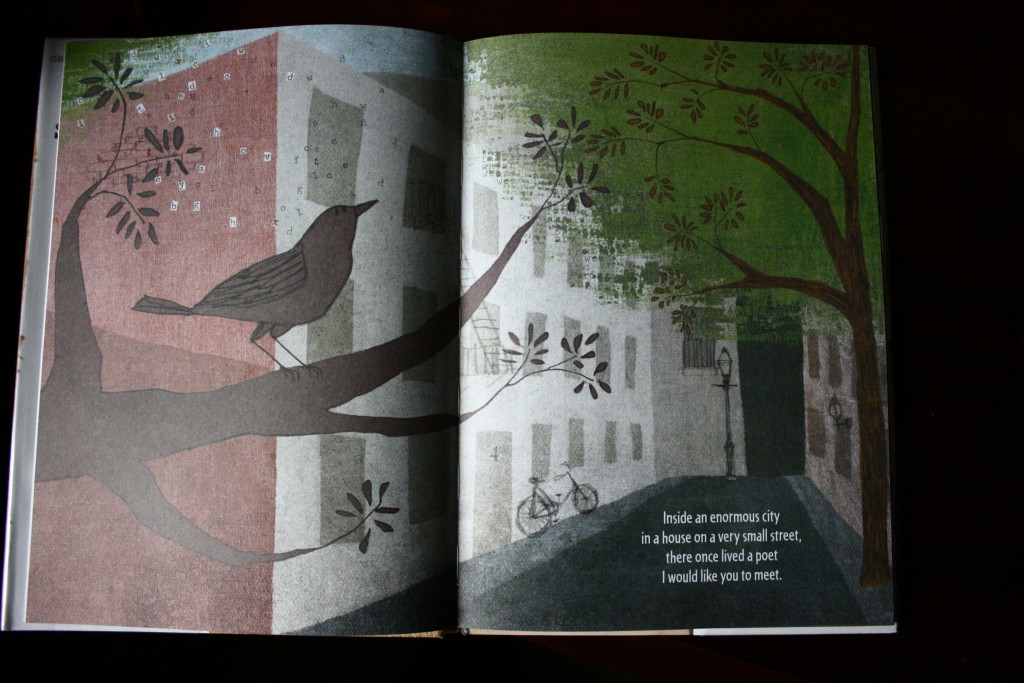

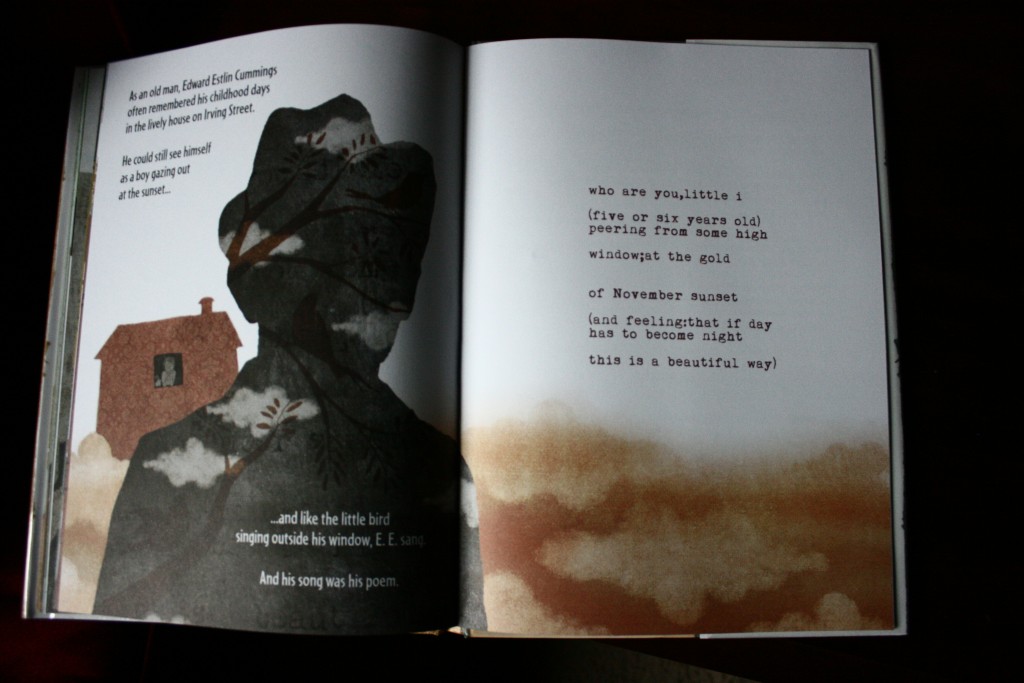

4. Enormous Smallness: A story of E.E. Cummings, written by Matthew Burgess and illustrated by Kris Li Giacomo.

Enormous Smallness is a nonfiction picture book that is very dear to my heart—mostly because e.e. cummings is one of my favorite poets.

Cummings, unlike the characters in the other stories, grew up in a well-to-do family, but he, too, was often overlooked as simply a “dreamer,” a boy who could not focus. No one knew the greatness that lived in him, though his parents understood it. There were stories of his mother writing down his early poems and his father letting Cummings ride his back to bed, asking Cummings to elaborate on the world they were traversing through.

The book included several of Cummings’s most popular poems, which I thought was fantastic. I’m always in favor of introducing my boys to the beauty of poetry, and this was a great way to do it.

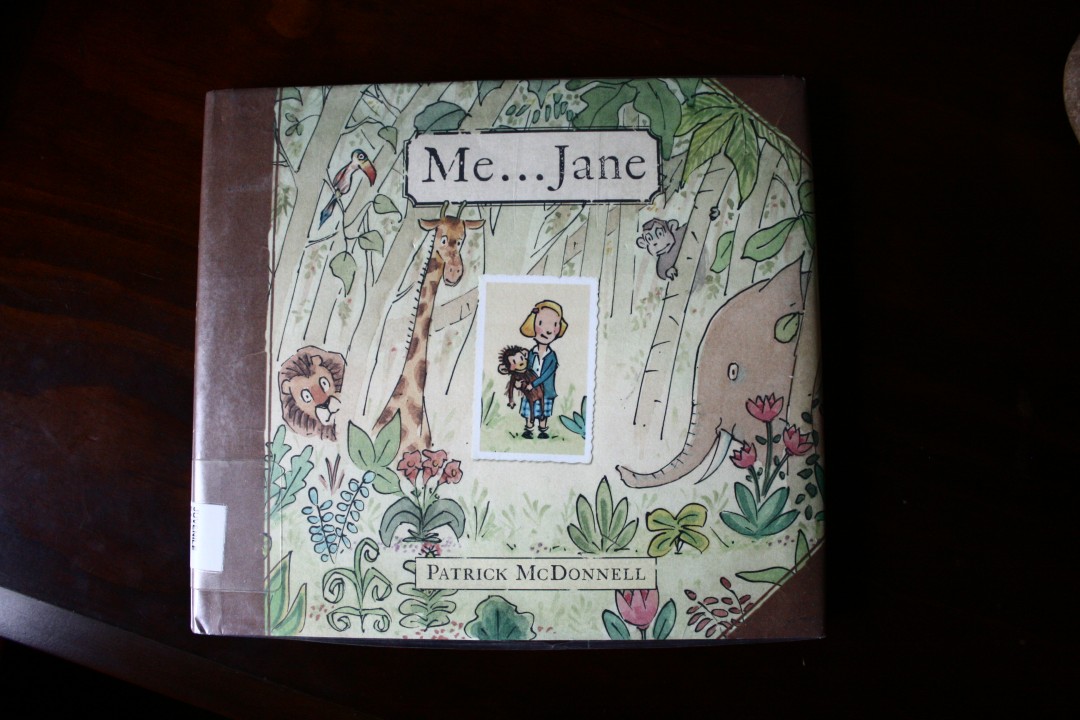

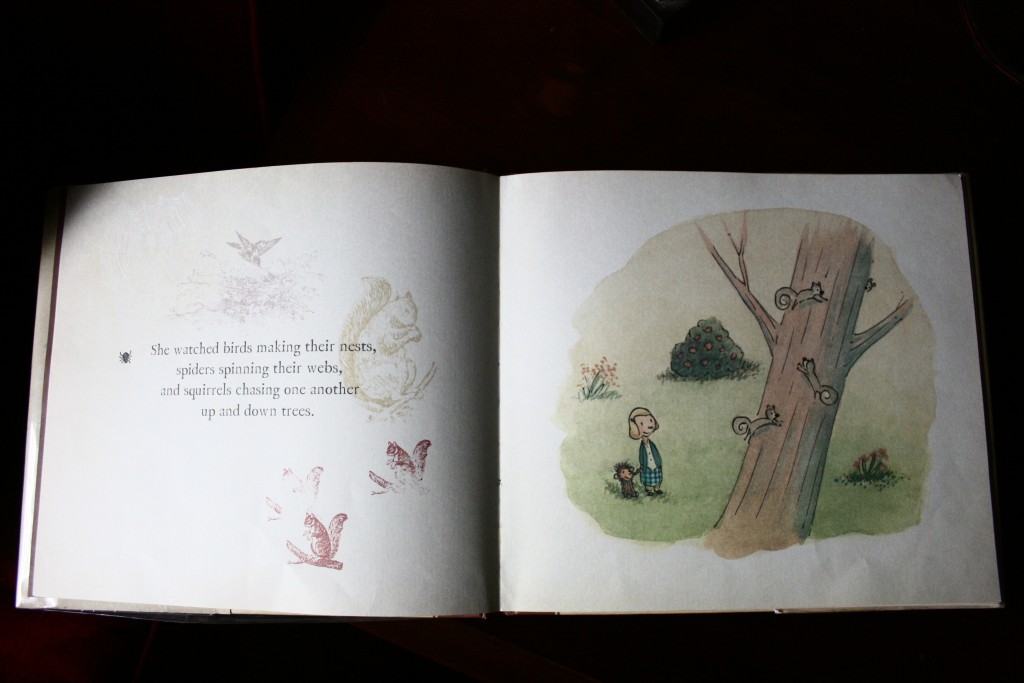

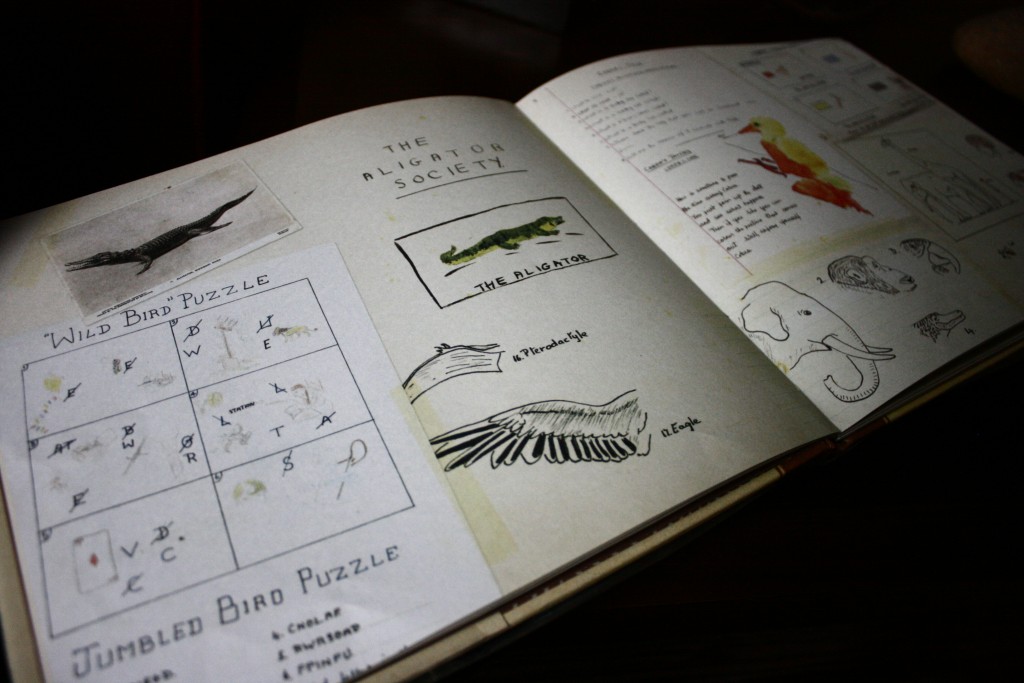

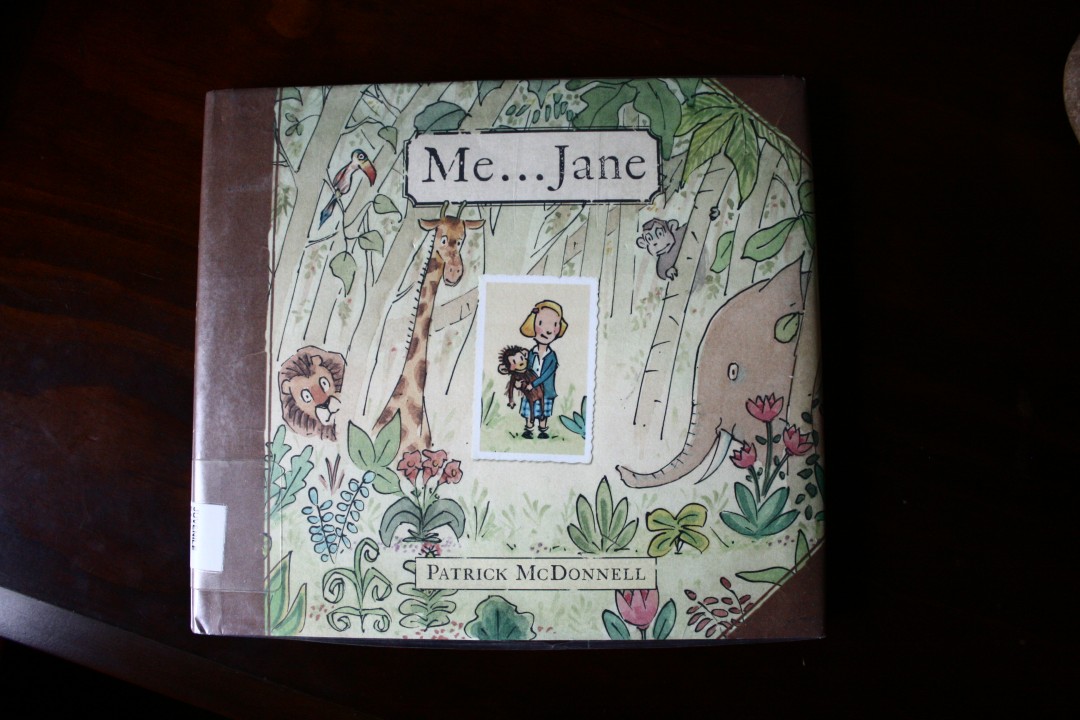

5. Me…Jane, by Patrick McDonnell.

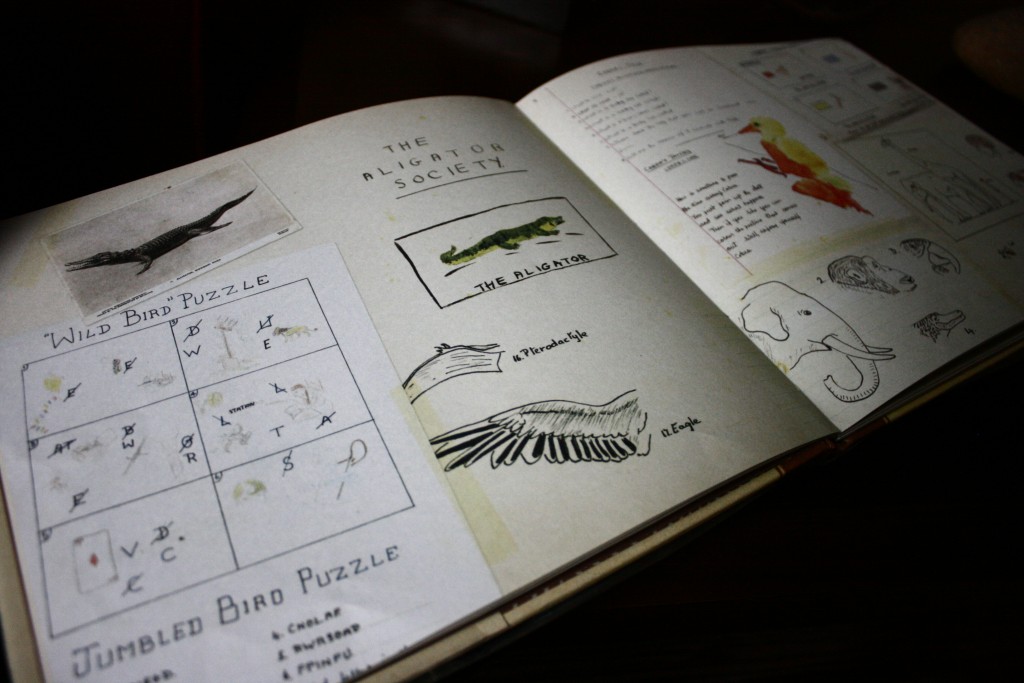

This book was a fantastic read about the life of Jane Goodall. It spanned her childhood, when even then she was highly interested in animals and the natural world. The illustrations were quirky and delightful, some of them containing animals, some of them containing field notes that Jane would pen when she was out in the natural world.

What I liked most about this one was that there was a personal note from Jane Goodall in the back of the book. Goodall urged her readers to become advocates for the natural world and the preservation of wildlife and natural resources. I found it incredibly inspiring, and as I read her message to my boys, I could already see their wheels turning. They loved to think that they could possibly make a differences in preserving the animals they already love.

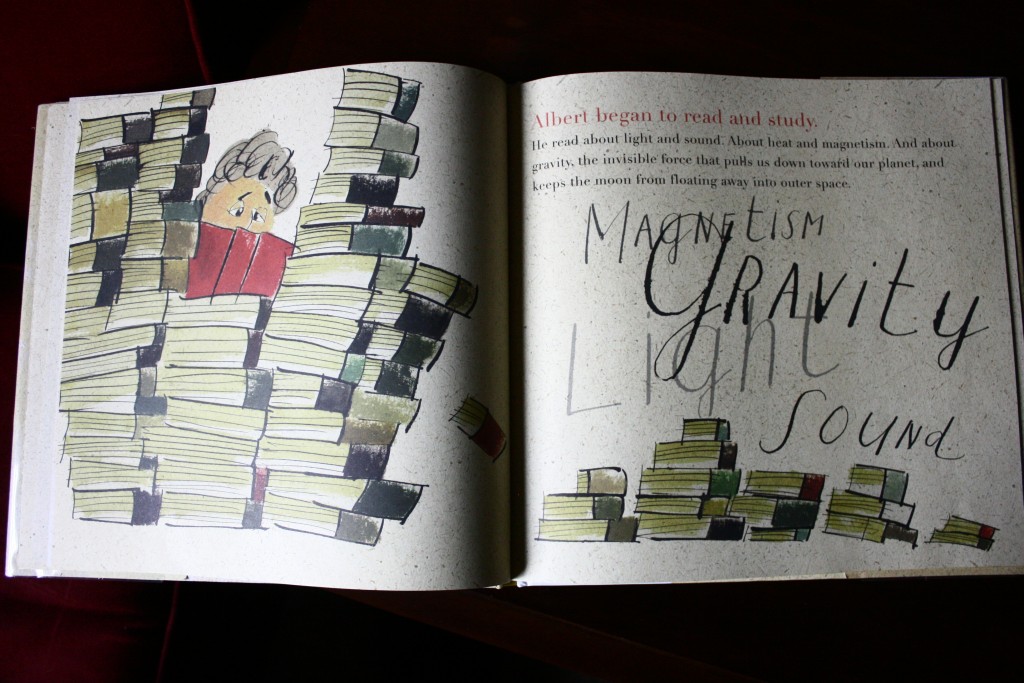

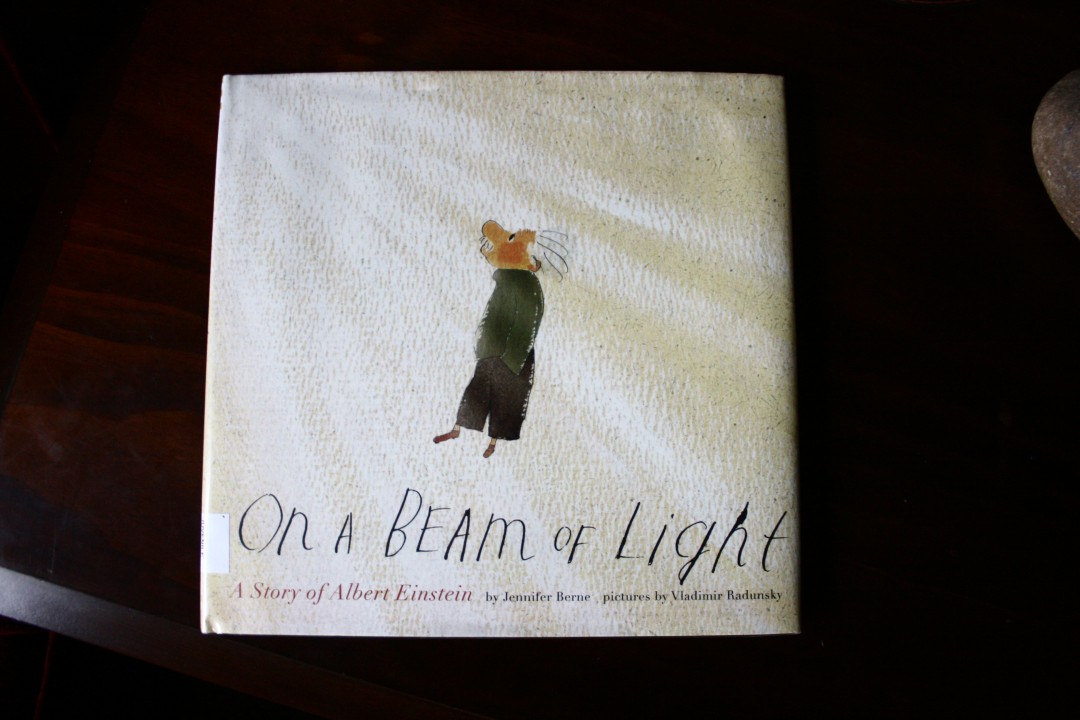

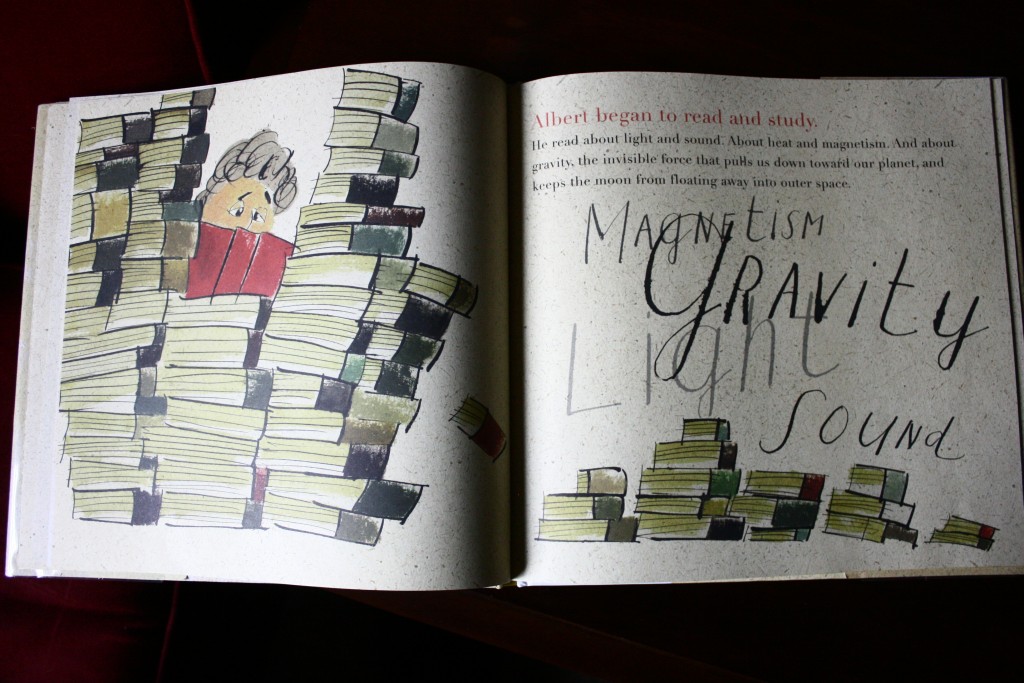

6. On a Beam of Light: A Story of Albert Einstein, written by Jennifer Berne and illustrated by Vladimir Radunsky.

This was a book that told of Albert Einstein from the time he was born to the time he was an old man. In a charming and endearing way, it highlighted the eccentricities of one of the greatest American minds to ever live. Any kid who has ever felt different or weird or discouraged by their seeming limitations will find this book a great relief. Einstein did not speak when he passed his second birthday. He lived in his head, where great questions swirled. His parents loved him unconditionally, and Einstein was able to overcome himself and achieve what no man had ever achieved at that time.

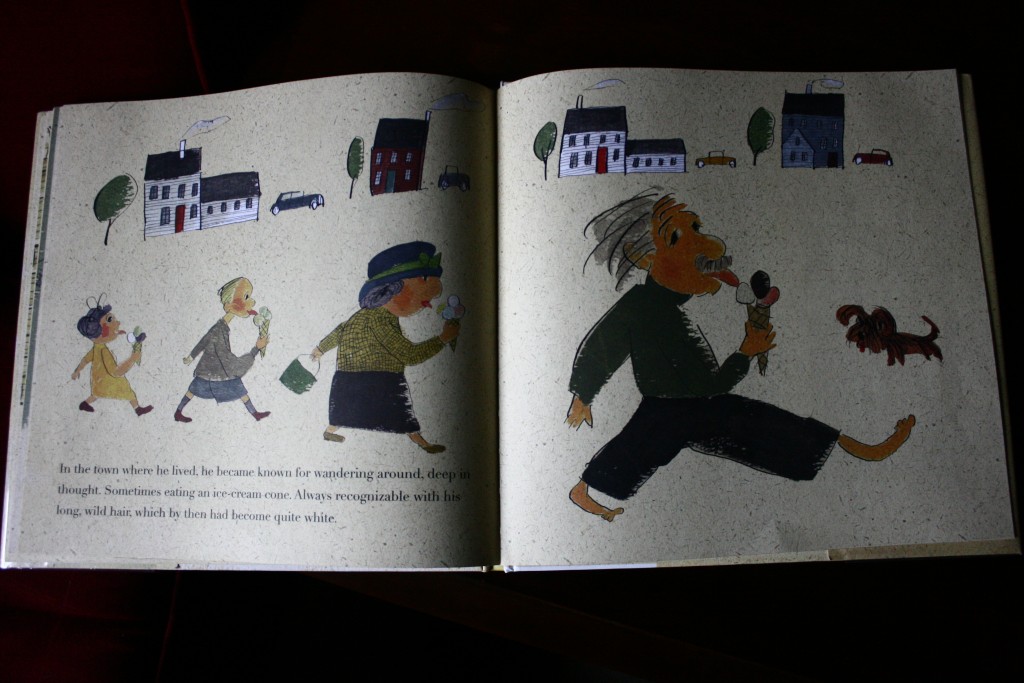

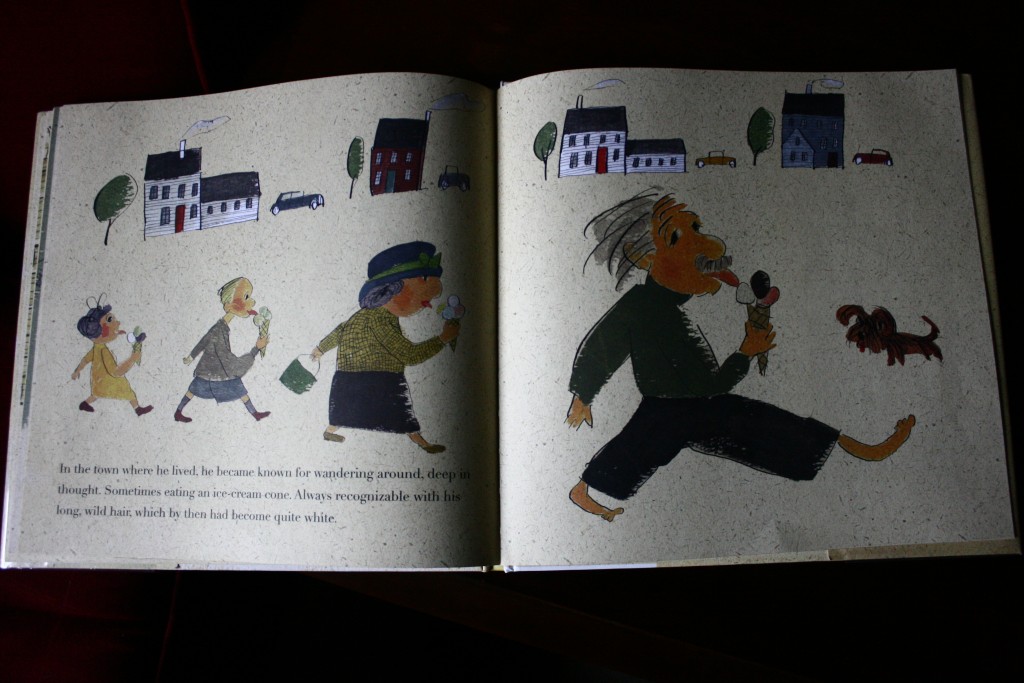

At the end of the book, there is a picture of Einstein strutting through his town where other people walk. The text says: “In the town where he lived, he became known for wandering around, deep in thought. Sometimes eating an ice cream cone. Always recognizable by his long, wild hair, which by then had become quite white.” There’s the Einstein we know, that strange and brilliant mind. My boys found this picture humorous and entertaining.

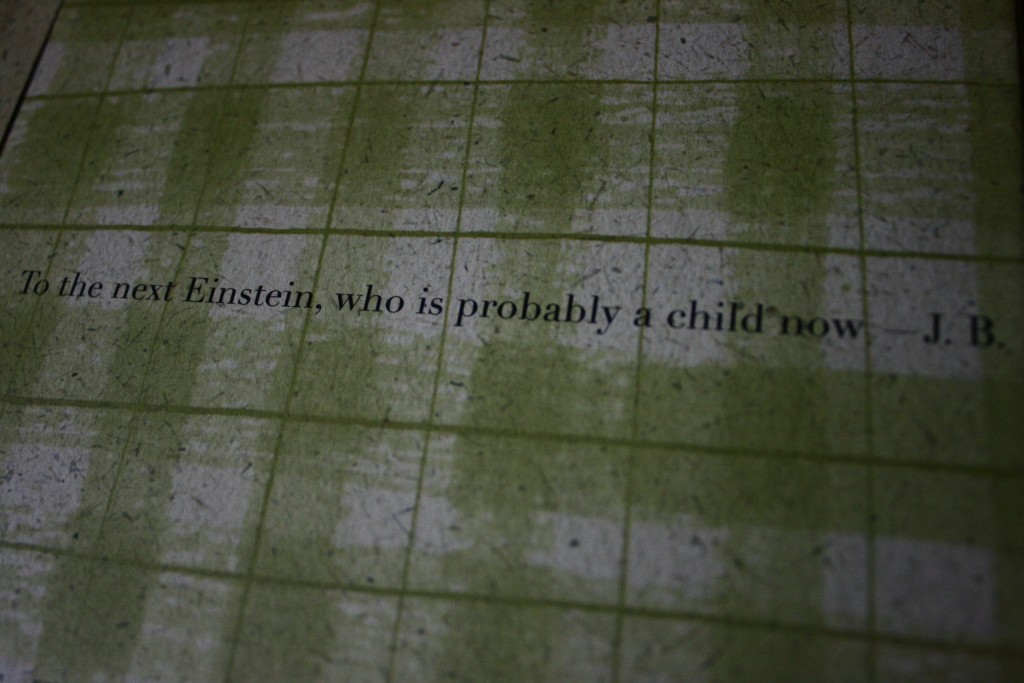

One of my favorite parts of the book was the dedication page, where the author wrote, “To the next Einstein, who is probably a child now.”

These books are all fantastic reads that introduce kids, through both lyrical and sometimes humorous text and beautiful illustrations, to some of the most inspirational stories in history. My boys are already asking to read more nonfiction picture books, because they, like most people, are inspired by the stories of real people. It’s important for kids to know the stories of hard work and grit that live in the people whose names they learn in science or writing or mathematics or history or, even, dance. Picture books telling those stories are the perfect way to nurture their interest in something real and true. I found these books to be a wonderful place to start.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

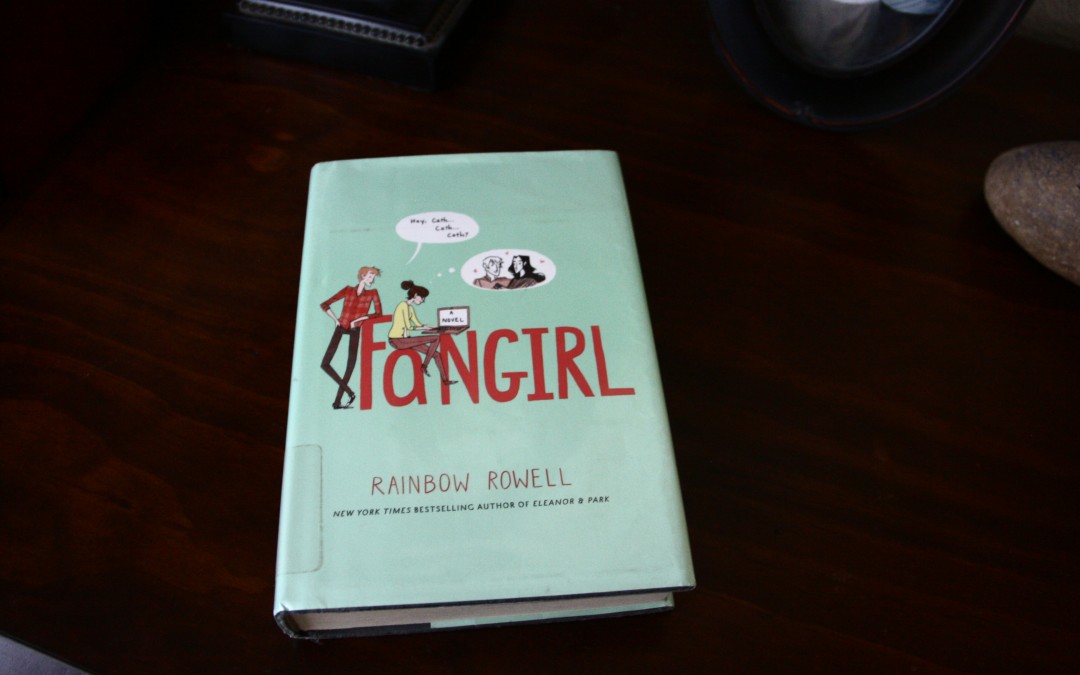

I’ve mentioned before that when I find an author I like, I will read everything in the world they have to offer. One of those authors is Rainbow Rowell.

I found Rowell through Eleanor & Park, which I read after a friend of mine told me it was one of her favorite young adult reads. I’m not a big young adult reader, but I thought I’d give it a try. It was so exceptionally written, so exceptionally true, so exceptionally part of the high school experience I remember that I had to see what else Rowell had up her sleeve. So I embarked on Fangirl.

Fangirl takes place at a different time and in a different era in a young adult’s life: college. It follows the story of twin sisters, Cath and Wren, who are learning to navigate the choppy waters of college. Wren wants to be on her own, build an identity outside of her identical twin sister, and, for the first time in their lives, Cath does not share a room with her sister. Cath is much more bothered by this than is Wren, who was always better at making friends. So Cath hides herself away in her fan fiction, which she writes for a large following. Wren, meanwhile, hides herself away with partying and alcohol.

During the story, the two sisters struggle with their relationships and their own identities. One of the best aspects of the book was all the issues it explored—alcoholism, the forgiveness of an absent mother, caring for a mentally ill father. It was an important contribution for the world of young adult literature.

One of the strengths of Rowell’s writing is her grasp on characters. In her stories, the characters fly off the page and into the reader’s life. They are real people with real problems and real struggles. They are some of the most believable characters I’ve ever read. Rowell has great insight into the human condition and also the life of a young adult, which is probably why her books are so popular.

Take this scene between Cath and her father:

“He was wearing gray dress pants and a light blue shirt, untucked. His tie, orange with white starbursts, was stuffed into and hanging out of his pocket. Presentation clothes, Cath thought.

“She checked his eyes out of habit. They were tired and shining, but clear.

“Cath felt overwhelmed then, all of a sudden, and even though this wasn’t her show, she leaned forward and hugged him, pressing her face into his stale shirt until she could hear his heart beating. His arm came up, warm, around her. ‘Okay,’ he said roughly. Cath felt Wren take her hand. ‘Okay,’ their dad said again. ‘We’re okay now.’”

It is clear that Cath’s father loves her, but it is also clear that Cath loves her father. Cath and Wren’s mother left when the girls were very young, and it’s only been the three of them for as long as they can remember, and this scene is a perfect mirror into that internal life. One gets the impression that their father has told his daughters those words all their life: “Okay. We’re okay now.” It’s a scene fraught with emotion and unspoken remembrance, one that, somehow, speaks of universal experience.

Rowell also has a practiced hand at dialogue, which is probably the result of her knowing her characters so well.

Here’s another great characterization passage, shown mostly through the description of a character:

“Reagan was looking at Nick like she was already tying him to the railroad tracks.

“Wren was looking at him like she was one of the cool girls in his stories. Oozing contempt.

“Levi was smiling. Like he’d smiled at those drunk guys at Muggsy’s. Before he’d talked Jandro into throwing a punch.”

Each unique description shows so much personality. It’s clear that Rowell knows her characters and exactly how they would react to the same situation.

Rowell also has a way of sneaking truth into her passages. Every writer will understand this passage between Cath and her creative writing professor:

“‘But Cath—most writers don’t. Most of us aren’t Gemma T. Leslie.’ She waved a hand around the office. “We write about the worlds we already know. I’ve written four books, and they all take place within a hundred and twenty miles of my hometown. Most of them are about things that happened in my real life.’

“’But you write historical novels—’

“The professor nodded. ‘I take something that happened to me in 1983, and I make it happen to somebody else in 1943. I pick my life apart that way, try to understand it better by writing straight through it.’

“‘So everything in your books is true?’

“The professor tilted her head and hummed. “Mmmm…yes. And no. Everything starts with a little truth, then I spin my webs around it—sometimes I spin completely away from it. But the point is, I don’t start with nothing.’”

Because Cath was a budding writer, Rowell inserts some passages about writing.

“This wasn’t good, but it was something. Cath could always change it later. That was the beauty in stacking up words—they got cheaper, the more you had of them. It would feel good to come back and cut this when she’d worked her way into something better.”

“Sometimes writing is running downhill, your finger jerking behind you on the keyboard the way your legs do when they can’t quite keep up with gravity.”

Rowell also utilizes great descriptions to write her deep scenes and give her readers a look into the lives of the characters. Here is a description of Cath’s room, when a boy is seeing it for the first time:

“It looked like a kid’s room now that she was imagining it through his eyes. It was big, a half story, with a slanted roof, deep-pink carpet, and two matching, cream-colored canopy beds.”

It’s almost as if Rowell walked into the room and looked around and then described it from memory. She is fantastic at setting scenes like this, pulling a reader in as if they are the ones merely observing.

“Cath put on brown cable-knit leggings and a plaid shirtdress that she’d taken from Wren’s dorm room plus knit wristlet thingies that made her think of gauntlets, like she was some sort of knight in pink, crocheted arms. Levi’s teasing her about her sweater predilection had just made it more extreme.”

I love this passage because of the way it pulls us into the time period when Cath is experiencing her college days. Rowell uses the fashion of the day to pulls us into the scene.

Rowell is also a master at providing filler information.

“Wren lifted her head and wiped her eyes with the back of her thumbs.”

One could imagine Wren doing exactly that.

And, of course, there’s enough romance in the book to make your knees all weak and your stomach fluttery. You care about the characters so much you’re just glad that they’ve found something as elusive as love.

“He called to tell her he was back. Knowing they were in the same city again made the missing him flare up inside her. In her stomach. Why were people always going on and on about the heart? Almost everything Levi happened in Cath’s stomach.”

If one has ever felt the stirrings of desire, one knows it doesn’t happen in the heart at all. It happens much deeper, and so we can empathize with Wren and her developing love.

Other passages deftly communicated the tone of the romance between Cath and Levi, the way new love is all senses, all poetry, all exciting and beautiful and scary and, mostly, wonderful.

“His heart beat in the palm of Cath’s hand, right there, like her fingers could close around it…”

“Love was all soft motion and breath, curves and warm hollows. Levi’s chest was a living thing.”

Cath thinks in metaphor and poetry:

“Cath was pretty sure that Levi actually was the brightest thing in the room, in any room. Bright and warm and crackling—he was a human campfire.”

“She didn’t have words for what Levi was. He was a cave painting. He was The Red Balloon.”

Rowell’s stories are not just good stories—they are instructional texts, showing writers how to create believable characters, how to write deep scenes, how to talk about romance and new love in a way that will inspire love in the hearts of readers.

Much like Eleanor & Park, Fangirl is a fantastic contribution to the young adult world, examining not only tough issues but also, subtly, showing what it means to really love.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

I’ve begun studying the art of memoir writing and have a great long list of memoirs to read this year, since this is the nonfiction writing I feel the most drawn to write. Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club was one of the first on my list of memoirs to study, and I’m glad I picked it first.

Karr writes with the brilliance of a poet (which, if you’ve noticed a theme in this book blog it’s that I love poetic writing). She tells her stories with great emotion and carnality, in a way that puts you right into the scene with her. She writes truth on the page, interspersed with the stories of her childhood, which serves to widen her specific experience into the shared experience of others, details aside. She is writing about humanity as much as she is writing about her family.

Karr’s story navigates through her tyrannical grandmother, her mother’s Nervous condition, the split-up of her parents, their getting back together and on into her father’s death when she was a young woman.

One of the aspects of The Liars’ Club that I enjoyed the most is that she is unashamed to say that her memory is not always the same as others in her life. It makes me trust her more, because memoirists who claim to recall everything perfectly from their earliest memory on are usually lying. But Karr’s confessional truth about relying on memory, that being a slippery thing, makes me trust her all the more with the story she tells.

Here’s how she puts it:

“When the truth would be unbearable the mind often just blanks it out. But some ghost of an event may stay in your head. Then, like the smudge of a bad word quickly wiped off a school blackboard, this ghost can call undue attention to itself by its very vagueness. You keep studying the dim shape of it, as if the original form will magically emerge. This blank spot in my past, then, spoke most loudly to me by being (missing). It was a hole in my life that I both feared and kept going back to because I couldn’t quite fill it in.”

This is the way of memory. We know from experience that when we try to remember those places that are too painful to remember, they seem to elude our grasp. The mind has a mysterious way of protecting itself. Sometimes we have great chunks of our lives that we cannot remember because our mind has blocked it out. But those holes are like whirlpools; we’ll always circle back to them, pulled into their depths.

At other times, Karr admits to not remembering something by admitting that her sister would tell a different story (or perhaps her sister doesn’t remember it correctly). What this serves to do is show us that we all interpret our lives in different ways. What one remembers is not necessarily what another would remember.

She writes about a birthday memory going dark on her:

“I sucked up as much air as I could get and blew the whole house dark.”

She is blowing out candles, which are keeping the house lit, and when she blows them all out, not only does the house go dark, but so does her memory.

I love the lyrical nature of Karr’s writing. Her sentences are structured beautifully, and though she is telling the true story of her life, it doesn’t feel like an autobiography. It feels like a story. It feels like a commentary on life. It feel like one great long string of what it means to be human. In one place she writes about going through a hurricane when she was just a little girl, and though I’ve never actually been through the horror of a hurricane, I felt like maybe I had. I’ve been through other hurricanes, the life kind, and it seems they’re very much alike. This is what Karr’s writing does: links a very physical detail of human existence with some emotional detail of human existence.

Her description are incredible. Here, she’s writing about a loogie her sister smeared on her:

“She hawked up a huge bogey gallop from way back in her throat, passing every now and then to tell me she was fixing to suck it at me. It had bulk and geometry. It was hanging in a giant tear right over my face, swinging side to side like a pendulum, when Daddy came slamming out the screen to haul her off me.”

This passage made me laugh out loud, not just for its gross description but also from the way it showed so perfectly this relationship between her and her sister as kids.

Here’s another great commentary on the sibling relationship (her sister has been stung by a man-of-war and has the marks down her leg):

“By the next day, she was charging neighbor kids a nickel to see her blisters, a dime to touch one, and a quarter to pop one with a straight pin we’d dunked in alcohol. Sometime during those transactions, she got mad at me and eventually got out of bed to stuff me once more into the dirty clothes hamper that pulled out from the bathroom wall. I heaved my body against the hamper to open it a slot, but the heavy lid fell back closed and mushed my fingers before I could get out. I wished her dead again, Lecia. I sat in the dark among the sandy towels and damp bathing suits for nearly an hour before she finally let me out. It seems Daddy had gone back to work, and Mother had gone to bed for the foreseeable future. There was no one else around.”

Another time, her sister told her that their mother had hauled their dead grandma in the back of their car.

“For years Lecia had me convinced that Mother left us behind because she was hauling Grandma’s body in the backseat of the Impala. Lucia fed me this lie pretty soon after we got off the phone with Mother that night, and I swallowed it like a bigmouthed bass. I needed an excuse for being left behind, I guess. The truth—that we were murder on her nerves, which were already shot—must have been too much for me.”

I love this passage for so many reasons. First, the image of swallowing what her sister told her, “like a big-mouthed bass.” She’s from Texas, and she’s slipping in a fishing reference, which is what people from Texas do. I also love her truthfulness here. She knows that she was probably too much for her mother to handle while she was trying to bury her own mother, but she felt slightly abandoned because of it.

At times, she writes irreverently, saying this of her grandmother’s death:

“I sat in the back of Uncle Frank’s white convertible going home with Lecia blubbering nonstop in the front bucket seat and him putting his hammy hand on her shoulder every now and then, telling her it was okay, to just cry it out. What was running through my head, though, was that song the Munchkins sing when Dorothy’s house lands on the witch with the stripy socks: ‘Ding dong, the witch is dead.’ I knew better than to hum it out loud, of course, particularly with Lecia making such a good show, but that’s what I thought.”

But what it really comes down to is her manner of description, how much she knows and understands about the people in her life, from this grown-up place, looking back on her childhood. Here is a description of her father. The details in this passage bring her father alive on the page:

“He had the easy glide of men who labor for an hourly wage, a walk that wastes no effort and refuses to rush. His barrel chest and legs were pale. There was a wide blood-colored scar up one shin where one of Lee Gleason’s quarter horses had thrown Daddy, then dragged him around the corral till six inches of white shinbone was visible on that leg. On the same leg, just above the knee, there was a knot of iron-blue shrapnel bulging under the skin left over from the war. Still, he didn’t limp one bit coming toward us. He had an amused squint on his face.”

And another:

“Evenings he wasn’t working, he sat in bed to study his receipts and bills. He liked to spread out the old ones stamped PAID along the left side of the bedcovers. The new statements still in their envelopes ran along the right. He’d worked out a whole ritual to handle those bills. When one hit the mailbox, he slit it open, then marked down what he owed over the front address window where his name showed through. That way he nodded at the debt right off, like he was saying, I know, I know. Plus, he then didn’t have to reopen and unfold every bill in order to worry over it. With all those envelopes staggered out in front of him, he drew hard on bottle after bottle of Lone Star beer and ciphered what he owed down the long margins of The Leechfield Gazette, all the time not saying boo about one dime of it.”

She knows the characters in her story so well. Here she is, speaking about her sister:

“I knew we’d never get back there and said as much to Lecia, who claimed that was the least of our worries. I looked at her serious profile while she watched the trees tick past. She had a way of tucking her chin in. Her head dipped down like a gull’s would facing a steep wind, so her brown eyes peered up at the world from a definite slot under her blond bangs’ sharp border. She drew her chin back further into her neck’s folds. That was her way of digging back into herself, of getting down deep in the solid foundation of what she was before another change swamped over her. Seeing her profile go all chinless in the car, I felt a whole flood of dark fill me up, cold as creek water. Daddy wouldn’t even know where to come get us when he got ready.”

In other places, the verbs make scenes come alive, like when she is describing being out in the Colorado open with her dad:

“Once the fire was high, Daddy swamped each little fish carcass around in a pie tin of cornmeal, then fried it in Crisco. I was hungry as only a day on horseback can make you. A canopy of evergreens waved overhead. Stars were bobbing into view in between. The fire kept popping to send whole handfuls of sparks skittering up in the air.”

And one day, when she is riding a horse back to the stables, after a long day out:

“The horse rocking me as he picked his way over stones had a rhythm like the Gulf, which until that night I’d never once thought of. It was a fetal rhythm, I guess, the kind that sneaks under your heartbeat and makes your brainwaves go all slack and your eyelids seam themselves together.”

One of my favorite passages was this one, a commentary on what it feels like to not have a dad:

“His kids spilled out of the truck and scattered, me hating every one of them for having a daddy. I wanted my own tall daddy to come there and make me a patch of shade with his big cool shadow.”

It’s so sad and so accurate. When you don’t have your dad around, you practically hate everyone else who does. Especially when she had a relationship like this with her dad:

“Just being out of the house with Daddy like this at Fisher’s lights me up enough for somebody to read by me.”

Mary Karr has the hand of a practiced poet in all of her stories that make up The Liars’ Club. She has written several memoirs, and they have now joined my to-read list.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

I try to read between two and five middle grade novels every month, mostly because that’s the genre I like to write in, and the best way to learn a genre is to read in it. One of the best middle grade novels I’ve picked up so far this year was The War that Saved My Life, by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley.

The story follows Jamie and Ada Smith, who are the children of a cruel woman. The novel is written around the historical time period of Britain’s involvement in World War II, when cities were getting bombed by the Germans. Ada has a club foot, and because of it, her mother treats her like a monster and won’t let her out of the house. She watches the world from her front window. But when the other children in their poor part of town start leaving because of bomb threats and their mother talks of sending her brother off and keeping Ada at home, Ada hatches a plan and steals out one early morning with Jamie. They are placed with a woman named Susan in a country home, where Ada discovers a love for horses and Jamie discovers a pet cat and they both discover what it means to be loved in this unknown world, where they eat more than they’ve eaten before in their lives.

The War that Saved My Life was a superbly written story, with so much emotion and wonder and ache. Readers will ache for Ada as she learns what it means to be loved unconditionally. Readers with ache for Jamie as he begins to miss his tyrant mother. Readers will ache for Susan, who grieves the loss of her partner and the other person she feels who really understood her, at least until these strange children come along. Bradley tells the story from Ada’s perspective, which is an engaging, innocent, lovable voice.

Some of my favorite passages were ones where Ada was talking about her brother. She loves him so clearly and desperately.

“Jamie had a mop of dirt-brown hair, the eyes of an angel and the soul of an imp. Mam said he was six years old, and would have to start school in the fall. Unlike me, he had strong legs, and two sound feet at the ends of them. He used them to run away from me.

“I dreaded being alone.”

This passage digs up so much fear and so much emotion. We see what Ada will lose when her brother starts school, though he is already running away from her now, roaming the town without her. But when he starts school, she will be alone for much more of the day, and he is her only companion, because her mother refuses to let her out of the house.

Ada also uses some remarkable powers of description. Here, she is describing what it’s like in the train that is evacuating the children:

“The day got worse. It was bound to. The train stopped and started and stopped again. Hot sun poured through the windows until he air seemed to curdle. Small children cried. Bigger ones fought.”

We see not only what the situation was like from a 10-year-old’s perspective, but we also see a little of her pessimism: “The day got worse. It was bound to.” I was immediately drawn to her because of her observation.

And here she’s describing the house where they are taken after getting off the train, the home of Susan Smith:

“The house looked asleep.

“It sat at the very end of a quiet dirt lane. Trees grew along both sides of the lane, and their tops met over it so that the plane was shadowed in green. The house sat pushed back from the trees, in a small pool of sunlight, but vines snaked up the red brick chimney and bushes ran rampant around the windows. A small roof sheltered a door painted red, like the chimney, but the house itself was a flat gray, dull behind the bushes. Curtains were drawn over the windows and the door was shut tight.”

This is a great description of the place that ends up also being a great description of the woman who lives there: “Curtains drawn over the windows and the door was shut tight.” It will take children to fling open the windows.

Some of the emotion-filled passages were seen in the way Ada was trying to work out the difference between Susan Smith and her mother. Susan had called herself “not a nice person.” Ada tries to reconcile this:

“She was not a nice person, but she cleaned up the floor. She was not a nice person, but she bandaged my foot in a white piece of cloth, and gave us two of her own clean shirts to wear. They hung past our knees. She combed or cut the tangles out of our hair, which took ages, and then she made a big pan of scrambled eggs. ‘It’s all the food I have,’ she said. ‘I haven’t been shopping this week. I wasn’t expecting you.’

“All the food she had, she said, except there was butter on the slightly stale bread, and sugar in the tea.”

This passage shows such a stark contrast between the home they left and this one where they find themselves. It’s almost an awakening of sorts, but the way Ada repeat the words, “She was not a nice person,” suggests that she is trying to work out for herself whether Susan Smith is a nice person or whether she is just another Mam. She does not yet trust Susan Smith.

When living in their mother’s home, Ada and Jamie hardly ever bathed. In their new place, they are expected to bathe every day. Ada tries to come to terms with this:

“There was hot water, soap, a towel. I already felt clean, but the water was soothing. Afterward I put on new clothes called pajamas, that were supposed to be just to sleep in. Tops and bottoms, both blue. The fabric was so soft that for a moment I held it against my face. It was all soft, this place. Soft and good and frightening. At home I knew who I was.”

Ada does not know who she is in this new place, but she’s also terrified of leaving it. She doesn’t know how long they’ll be able to stay there, and she doesn’t really want to find her place, because she’d rather just expect the worst. She holds it all at arms’ length, but this is a passage that reveals the truth of her feelings, how she wants—no, longs—to pull it all close and hold it against her, if only for a moment.

Ada begins breaking during her stay with Susan Smith:

“Why would I cry? I never cried. But when I shook myself free of Miss Smith’s grasp, tears shook loose from my eyes and slid down my cheeks. Why would I cry? I wanted to hit something, or throw something, or scream. I wanted to gallop on Butter and never stop. I wanted to run, but I couldn’t run, not with my twisted, ugly, horrible foot. I buried my head in one of the fancy pillows on the sofa, and then I couldn’t help it. I did cry.

“I was so tired of being alone.”

This is such a lovely passage. It is confusion and sorrow and hope. Ada is a little girl tired of being alone, so worried that the person she is coming to love is going to leave her, or send her away, like her Mam did. This woman has been so kind and soft where her Mam was loud and hard, and she doesn’t know how to accept it, because she has never known anything else. And yet she has never wanted anything else more.

I love this metaphor that Ada stumbles upon, after reading The Swiss Family Robinson with Susan. She and Jamie have just asked what tempest-tossed means:

“Miss Smith liked at me over her mug of tea. ‘Caught a storm,’ she said. ‘Wind and rain and lightning, and if you’re in a boat, at sea, you get tossed from side to side. You’re all thrown about, because of the storm.’

“I looked at Jamie. ‘That’s us,’ I said. ‘All thrown about. We’re tempest-tossed.’ He nodded.”

When Susan touches her for the first time, Ada says this:

“It felt very odd to have her touch me. Of course it made me tense. But I didn’t go away inside my head. I sat on the sofa with Miss Smith’s arm around me, and Jamie breathing soft near my shoulder, and I watched the coal fire flicker, and I stayed right there, right there in that room, and none of us moved for half an hour. Jamie fell asleep, and Miss Smith and I just sat, neither of us saying a word, until it was time to put the blackout up, and make tea.”

She is not used to a loving touch, only one that is harsh and unkind, and it’s not only something that she has to get used to, but it’s something that she longs to have, as most children do, and is afraid she won’t get ever again.

The first passage to make me cry was this one:

“I hold perfectly still while she took off my sweater and blouse, and settled the green dress over my head. ‘Step out of your skirt,’ Susan said, and I did. She buttoned the dress and stepped back ‘There,’ she said, smiling, her eyes soft and warm. ‘It’s perfect, Ada, you’re beautiful.’

“She was lying. She was lying, and I couldn’t bear it. I heard Mam’s voice shrieking in my head. ‘You ugly piece of rubbish! Filth and trash! No one wants you, with that ugly foot! My hands started to shake. Rubbish. Filth. Trash. I could wear Maggie’s discards, or plain clothes from the shops, but not this, not this beautiful dress. I could listen to Susan say she never wanted children all day long. I couldn’t bear to hear her call me beautiful.”

It’s such a tragically beautiful passage that will grip those who have ever been hurt by one they loved and, at the same time, mend the pieces of their heart. It is difficult for a child to get the cruel voice out of their heads, so the kindness of another person makes a child feel angry and afraid. Ada is trying to figure out who it is who’s telling the truth, and it’s easier for a child like her to believe the terrible things than it is for her to believe the good ones.

In several of the passages between Susan and the children, Bradley slips in her behavior-philosophies, which I love, since these are philosophies we teach our children, too:

“‘It’s okay,’ I said, slipping my arm around his shoulders. ‘I was bad.’ I wondered if the presents were all for Jamie. Could any possibly be for me?

“‘Not bad,’ Susan said. She helped me down the last few steps. ‘Not bad, Ada. Sad. Angry. Frightened. Not bad.’

“Sad, angry, frightened were bad. It was not okay to be any of those. I couldn’t say so, though, not on that gentle morning.”

Susan is one who believes that our emotions are not who we are, and she tries to explain that to the children, though the damage of their Mam is a persistent damage to overcome.

In this passage, Ada wrestles with all her feelings:

“It was scary, how angry I felt inside. At Susan, for being temporary. At Mam, for not caring about us. At Fred, for wearing the scarf I had knit him from his wife’s wool every day, as though it was something special, when I could see myself how I’d dropped some stitches and picked up others, so that the scarf was full of holes.”

For Ada, her sadness manifests itself as anger. She feels anger because she is sad about all those things. She is caught in a place where she does not know what will happen tomorrow, and she doesn’t know how to reconcile that instability and not-knowing with anything else but anger. Anger is easier than sadness.

Ada, at times, is profound:

“I had so much. I felt so sad.”

“There was a Before Dunkirk version of me and an After Dunkirk version. The After Dunkirk version was stronger, less afraid. It had been awful, but I hadn’t quit. I had persisted. In battle I had won.”

This last passage accurately shows what happens to kids in adversity. Ada understands that even though she has endured something tough, she has come back out stronger and braver than she was before.

The War that Saved My Life was beautiful all the way through, deserving of its Newbery Honor recognition through and through.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

For the past year, I’ve been studying the art of humor writing, because I run a parenting humor blog, and I didn’t want it to be just run of the mill. There are so many humor writers who make their living from what I call roasting—making fun of people who are in the same camp they are, and I’ve found that it rubs me the wrong way.

So when I discovered the classic humor of Erma Bombeck, who was a humor writer in the 1960s (and on) published in a syndicated newspaper column, I knew I needed to channel HER. She wrote about suburban home life and described it so hilariously—without throwing her peers under the bus—that I was instantly drawn to her. I’ve now read five of her books.

The most recent one I finished had even a hilarious title: When You Look Like Your Passport Photo, It’s Time to Go Home. I took notes copiously throughout the book, trying to study what it was about her that made her so funny.

Most of the time she uses self-deprecating humor.

When she and her husband were on a cruise ship for several days, she told a story about how all they would do was eat, eat, eat. They were growing large. Here was a response from her husband when he told her they needed to do something about all this eating and she dared ask the question, “Why?”

“Let me put it this way. If someone wants to show home movies, all you have to do is wear white slacks and bend over.

“I looked in the mirror. He was right. I was beginning to dress like the Statue of Liberty. I held out my arms and fanned the skin that hung like a stage curtain. It was only a matter of time before fourteen tourists would fit in my arm. I couldn’t go home like this.”

She uses humor to make fun of herself (and her family at times) but also employs one of my favorite humor techniques—exaggeration.

When she and her husband get lost in a foreign country, on their way to the airport, she says this to her husband:

“I don’t want to panic you, but our plane leaves in four days.”

When her husband tells her he wants to go out jogging in the African bush, this is her response:

“No one is going to feel sorry for you because you’re stupid. We’re going to ship your body home and prop it up in the Boston Marathon. It will be hours before people realize you’re not moving under your own steam.”

I laughed out loud at that one, because it creates such a humorous image, and speaks just a little bit of truth, too.

“I don’t understand people who can go abroad and come back with nothing to declare but diarrhea,” she says. This sentence is so blunt and unexpected that I could not help but laugh. I’ve been abroad. And I did come back with diarrhea.

Other self-deprecating examples:

“I was being held captive on a no-frills ship of geologists, zoologists, and botanists who cared about the preservation of the world but nothing about toilet tissue. I hate to make generalizations, but there is a definite correlation between smart people and little regard for creature comforts.”

She is saying, essentially, that because she cares about these “creature comforts,” she is one of the not-smart people.

“At nights, I joined the group in the ship’s small lounge to listen to lectures, watch slides, and make notes on what we were to see the next day. No one suspected that in college, in response to the question, ‘What is a chinook?’ I wrote in, ‘The name of the guy I just broke up with.’”

At times, Bombeck takes a popular phrase and turns it around surprisingly:

“It has always been my theory that the family that plays together gets on one another’s nerves.”

And she uses surprise as an element of her humor, as in this passage:

“Standing at the south rim of the Grand Canyon, our family looked like an ad for constipation…Our daughter was ticked off because it was four in the morning and she didn’t want to be there. Her brothers were fighting because one of them was staring at the other one, and my husband didn’t know how he could possibly be on a raft on the Colorado River for six days with only a gym bag of clothes.”

Anyone who has traveled with a family will understand where she’s coming from.

Bombeck uses real-life humor often, which draws her readers to her. Anyone who has been a parent of teenage drivers understands the following (if a little exaggerated):

“I have survived three teenage drivers: one who used cruise control in downtown traffic at five p.m., one who put on full makeup and finished her homework while driving through a construction area, and another who got a ticket for driving forty-five miles per hour…in reverse. But this was unbelievable.”

I love that phrase at the end—“this was unbelievable”—which follows something that was really unbelievable—a driver getting a ticket for driving forty-five miles per hour in reverse.

Bombeck also has a hilarious passage on people trying to make their friends and family look at vacation slides (in her time—it could be translated to showing travel pictures or posting all your travel pictures on Facebook). But you’ll have to read the book to get that passage.

Bombeck is a master at turning a witty phrase:

“You don’t even know what fear is until you are out in the bush with eleven shutter-happy hunters who load film and shoot at anything that moves.”

“One (child) ran with the bulls through the narrow streets of Pamplona and told me later so I could have a heart attack at leisure.”

“We have paid as much as $300 a day to throw up in a sink shaped like a seashell.”

“From the rear, I looked like a Disney parking lot.” (She’s looking in the mirror wearing the full expedition costume.)

But lest you think When You Look Like Your Passport Photo It’s Time to Go Home is all fun and games, Bombeck also has a serious side. She pontificates on the shared hopes of humanity:

“Once you have looked into the eyes of people in a foreign country, you realize you all want the same thing: food on your table, love in your marriage, healthy children, laughter, freedom to be. The religion, the ideology, and the government may be different but the dreams are all the same.”

And, when speaking about a particular family trip that was the last her family would take as parents and children in an essay titled “Rafting Down the Grand Canyon, she says this:

“For the first time we could remember, we were a family who gave one another space to be ourselves. We had never done that before. It was as if we all knew that this was the end of a chapter in our lives and the beginning of a new one. The umbilical cord that had bound us together as a unit for nearly two decades was about to be severed.”

“From that day on, our lives would all turn in different directions. In many ways it was like the Colorado River. It would wind and twist with a promise of a new experience at each turn of the bend. There would be smooth waters for long stretches, then suddenly a patch of rough rapids that would test us and take away our control. It would demand everything we had to hang on and get back on course again.”

She finishes this essay with:

“It would be several years before we planned another family vacation. We all had a lot of thinking and growing up to do…a lot of things to prove to ourselves. But strangely, this was the trip that we all talk about and remember, the pictures we pore over in the family albums. We have never said it to one another, but it was the last summer of the child…the last summer of the parents. From that day on, all moved to become contemporaries.”

Makes me want to pack up my family right now and take them on a vacation.