by Rachel Toalson | Books

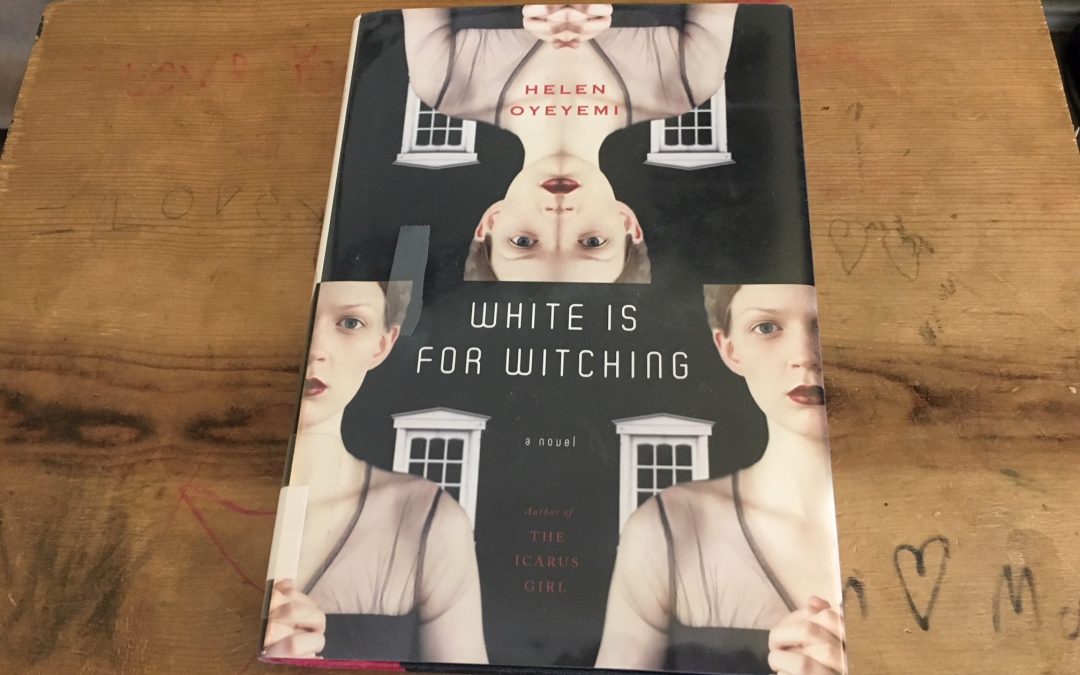

I’ve been doing some exhaustive research on mental health issues, depression, suicide, and mental institutions, and White is for Witching, by Helen Oyeyemi came up on my search for best books to read.

And it was fantastic.

The story is strange, creative, unusual, and interesting—yet another book I have no idea how to characterize. I’d call it an adult literary novel that examines madness and has a fantasy/horror feel to it.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about it:

The opposing viewpoints. Oyeyemi used different points of view to distinguish between the characters telling the story (first person, third person). All the characters were unique and interestingly strange in their own ways, all descending into their own forms of madness in very individual ways. It was fascinating. There were even some sections of the story told from the house’s viewpoint, which lent the novel a creepy sort of feel.

The unusual classification. The focus on characters would classify this book as a literary novel, but it was also unlike other adult literary novels—was it horror, or was it fantasy? I love books that break the rules, and this one certainly did.

The art. This was truly a book that I would qualify as art. At certain sections in the book, one point of view would finish with the same line that would begin another point of view, like a long narrative poem was unfolding before the reader’s eyes. I found it delightful.

Here are the brilliant opening lines:

Ore:

Miranda Silver is in Dover, in the ground beneath her mother’s house.

Her throat is blocked with a slice of apple

(To stop her speaking words that may betray her)

Her ears are filled with earth

(To keep her from hearing sounds that will confuse her)

Her eyes are closed, but

Her heart thrums hard like hummingbird wings.

Does she remember me at all I miss her I miss the way her eyes are the same shade of grey no matter the strength or weakness of the light I miss the taste of her I see her in my sleep, a star planted seed-deep, her arms outstretched, her fists clenched, her black dress clinging to her like mud.

She chose this as the only way to fight the soucouyant.

Eliot:

Miri is gone.

White is for Witching was probably one of the best, most interesting adult novels I’ve read in a long time.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

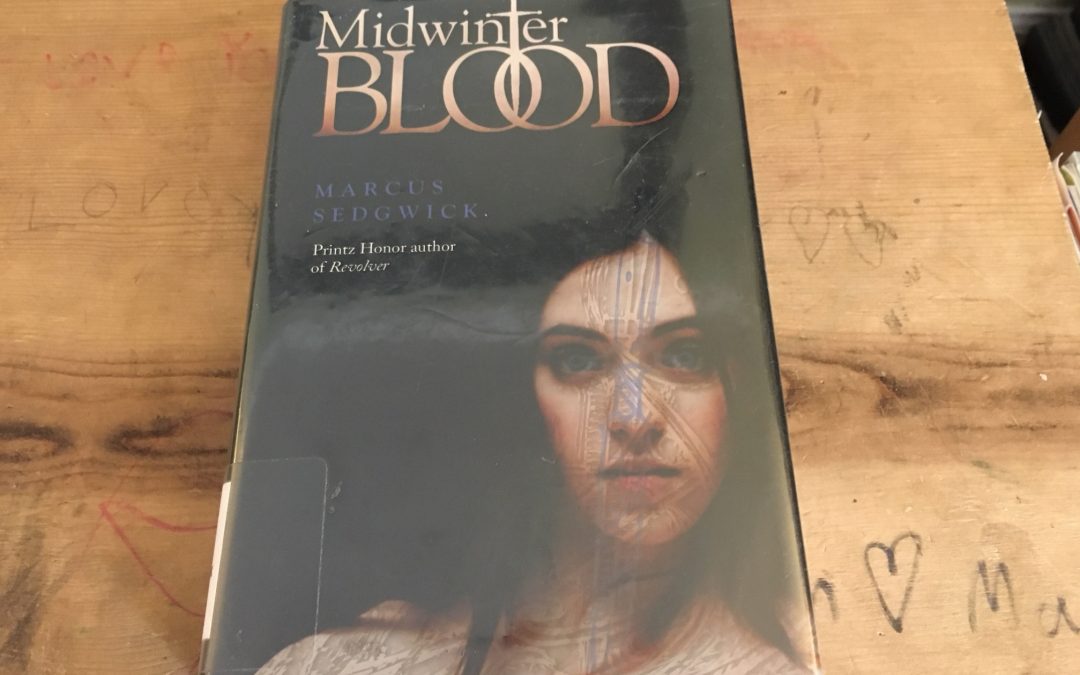

I’ve become a big fan of Marcus Sedgwick and his creative young adult novels. Midwinterblood is the second one of his books I’ve read, and it was just as good as the first one (The Ghosts of Heaven).

What I love about Sedgwick is that he’s very experimental with his narrative. This one was incredibly creative and beautifully written—tragic and yet hope-filled. I don’t even know how to categorize it: a young adult sci-fi paranormal about the enduring nature of love. It had all those elements.

Here are 3 things I enjoyed most about it:

- The seven stories. They were all tied together by characters with the same or similar names, and this drove the narrative—a mystery that needed solving. Where will we see them next? How will they know about each other?

- The artistic catchphrases. These weren’t cliche catchphrases; they were specific to the characters. One particular character used vocal tags like “well” and “So it is,” so even though the characters had different names in the different narratives, this helped readers identity who was who. It was a great technique for threading the stories together. There were also narrative elements like the dragon flower and hares, which connected the different stories to each other.

- The mystery and surprise. It was basically the same two characters living seven different lives, and part of the pleasure of reading this book was trying to predict whether or not they would find one another again.

Probably the best part of the book were the first lines:

“The sun does not go down.

This is the first thing that Eric Seven notices about Blessed Island. There will be many other strange things that he will notice, before the forgetting takes hold of him, but that will come later.”

Midwinterblood is a fantastic novel full of intrigue, mystery, and philosophical wonderings.

The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

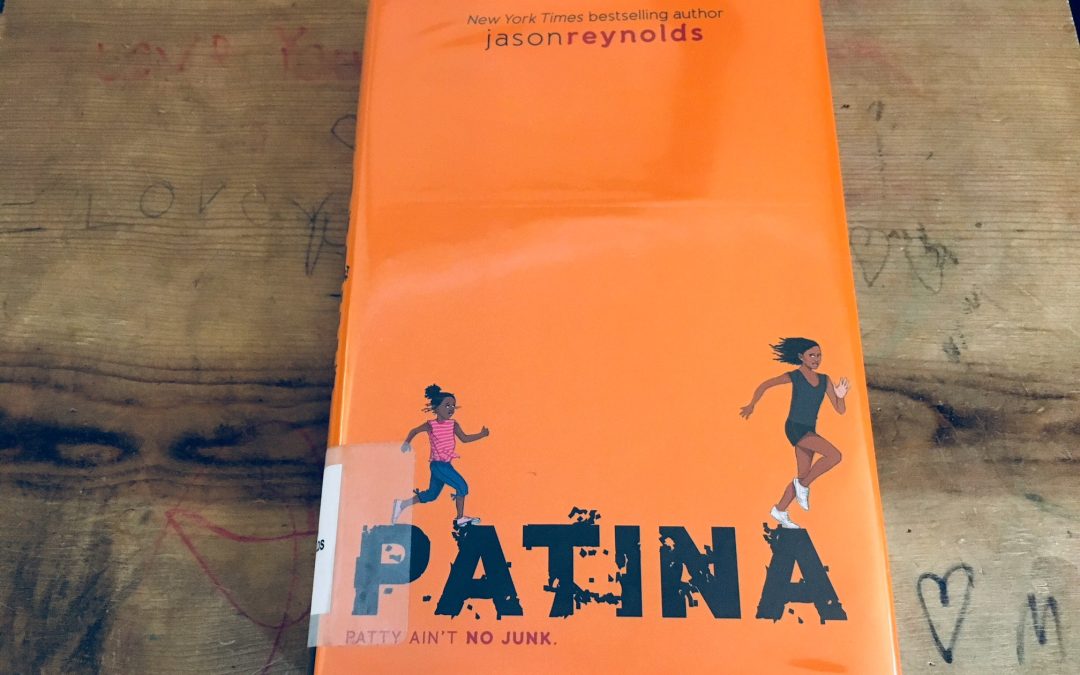

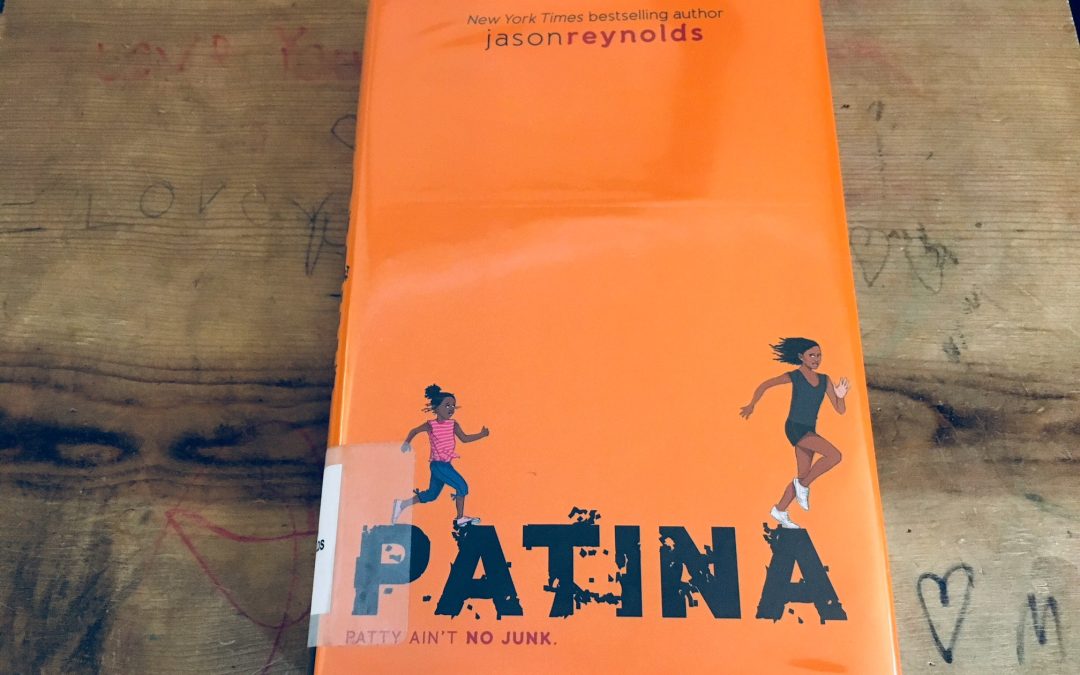

I am a super-fan of Jason Reynolds and read pretty much every book he comes out with—whether it’s middle grade or young adult. So it was with great anticipation that I picked up his newest book, Patina, the second in a semi-series about kids who run on a special community track team.

This book was just like any of Reynolds’s other books: sweet, engaging, thought-provoking, and necessary.

Patina (Patty) is a girl who feels she has to take on the responsibility of caring for her family, since her mother lost her legs to diabetes (she doesn’t like that diabetes has the word “die” in it, either), and she runs to get away from all those responsibilities.

Here are three things I enjoyed most about this book:

The character. Patty was an engaging character who reminded me of myself when I was 11, because she took on a lot of responsibility and stepped into the holes with her little sister. She was also a fighter and I loved that about her; she had opinions and grew into herself and those opinions as the book progressed.

2. The track element. I loved reading about track and Patty’s experience on a relay team and especially loved that she had to simultaneously learn how to be part of a team on the track and in her home. She had to learn how to trust that other people would take care of things, and she had to rely on them, too, to do what she needed to do.

3. The frame. Every chapter was framed by a to-do list; this depeened Patty’s personality and also was further evidence of how she changed as she began to grow into herself.

One of my favorite to-do lists was the very first one, which showcases Patty’s view of life at the beginning of the book:

“To do: Everything (forgetting about the race and braiding my sister’s hair.)”

This was followed by the first line, which further showcased Patty’s personality:

“Ain’t no such thing as a false start. Because false means fake, and ain’t no fake starts in track. Either you start or you don’t. Either you run or you don’t. No in-between. Now, there can be a wrong start. That makes more sense to me. Means you just start at the wrong time. Just jump early and break out running with no one there running with you. No competition except for your own brain that swears there’s other people on your heels. But ain’t nobody there. Not for real. Ain’t no chaser. That’s what they really mean when they say false start. A real start at the wrong time.”

Patina was another solid book from Reynolds. I can’t wait for my boys to read it.

*The above is an affiliate link. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them. But if you’re ever curious whether I’ve read a book and whether I liked or disliked it, don’t hesitate to ask.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

I read a whole lot of books over many different genres. This year I’ve read 155 old books and new releases so far. This is my list of the best among the best. We’ll do this countdown style.

Number 10

The War that Saved My Life, by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley. The story follows Jamie and Ada Smith, who run away from their cruel mother in the middle of World War II, when cities were getting bombed by the Germans. They find a new home but don’t know if they’ll be able to stay. They are damaged and wounded and scared, and the story is their coming to grips with what being a family means. It was superbly written, with aching emotion and beautiful language.

Number 9

The Argonauts, by Maggie Nelson. This narrative nonfiction book is a love story. It’s a meditation on what it means to be a family, what it means to be male and female. It’s a candid look at gender biases, motherhood, parenthood, the daily moments of life and what it means to be human. Nelson has a very poetic, beautiful style, and though it’s a shortish read, it’s in no way light material. I enjoyed every bit of it.

Number 8

I’m Thinking of Ending Things, by Iain Reid, which is one of the best literary thrillers I’ve ever read. It was a short read, but it was fantastic. I don’t want to give too much away in my summary, so I’ll just say that the book is about a woman taking a trip with her boyfriend, considering the entire drive whether or not she should end things with him. The significance of all her conversations and ruminations will come crashing in once you reach the end of the story. And you won’t be able to reach it fast enough.

Number 7

Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club. This is a memoir about Karr’s tyrannical grandmother, her mothers’ Nervous condition, the split-up of her parents, their getting back together and on to her father’s death when she was a young woman. It is written honestly and poetically, and one of the things I enjoyed most was Karr’s willingness to admit that her memory might not be entirely perfect, which is true for all of us. She tells the story as she remembers it.

Number 6

Salman Rushdie’s Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights. It’s hard to describe Rushdie’s style. He’s a masterful storyteller. Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights tells the story of the djinn, which were like genies in Arabian and Islamic mythology. But the way that Rushdie told this story was like a history of sorts. You had the feeling that you were reading a true account of how djinnis tried once to overtake the world and failed. It was strange and fantastic.

Number 5

All the Broken Pieces, a young adult novel by Ann E. Burg. This book is about a boy named Matt Pin who comes to live in the states after suffering some of the horrors of the Vietnam War. He carries around scars that he keeps hidden, because they’re shameful and frightening and too horrible to speak aloud. It’s a story full of emotion, beauty and redemption, written in verse.

Number 4

Doll Bones, by Holly Black—one of the creepiest middle grade books I’ve read. Doll Bones follows the story of Zach, Poppy and Alice, who are the kind of friends who play pretend and build elaborate worlds together. When Poppy comes to school claiming that the bone china doll in her mother’s cabinet is made from the bones of an actual little girl who needs to be buried, Zach and Alice grudgingly go on a quest with her. This is an engaging entertaining story with a creepy doll. Enough said.

And here I have to let you know that these next three are pretty much tied in my mind. But for the sake of continuity, I’ve separated them out and assigned them numbers. Just know that they are equally fantastic.

Number 3

Sophie Quire and the Last Storyguard, by Jonathan Auxier, which is the second Peter Nimble adventure from Auxier, is a wonderfully entertaining middle grade book. Sophie Quire is a bookbinder in the city of Bustleburgh, working at her father’s shop, Quire and Quire. She comes upon a mysterious book and sets out on a quest to find the others like it, joined by Peter Nimble, the greatest thief in the history of time, and his sidekick, Sir Tode. It’s written with great description, humor, wisdom and imagination.

Number 2

Kill ‘Em and Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul, by James McBride, a narrative nonfiction book that examines James Brown’s often-fabled life. McBride digs down to the truth of the funk legend and the book is by turns humorous, truthful, smart and probing. McBride nails the prejudice of the south, the life of musicians, and the realities of poverty, and conducts interview with people who best knew Brown and can shed the most light on his vices and victories. It was fascinating and lovely.

Number 1

Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows and I’ll give you a bonus—the sequel, Crooked Kingdom. Both of these young adult books follow six renegades in the city of Ketterdam who attempt heists unlike anything the world has ever seen. Everything about these two books was fantastic. They had the feel of a teenage Oceans 11, set in a fictional world. They were smart, complex and highly entertaining.

I hope you enjoyed these book recommendations. Be sure to pick up a free book from my starter library and visit my recommends page to see some of my favorite books. If you have any books you recently read that you think I’d enjoy, contact me. I always enjoy adding to my list. Even if I never get through it all.

*The above are affiliate links. I only recommend books that I personally enjoy. I actually don’t even talk about the books I don’t enjoy, because I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them.

by Rachel Toalson | Books

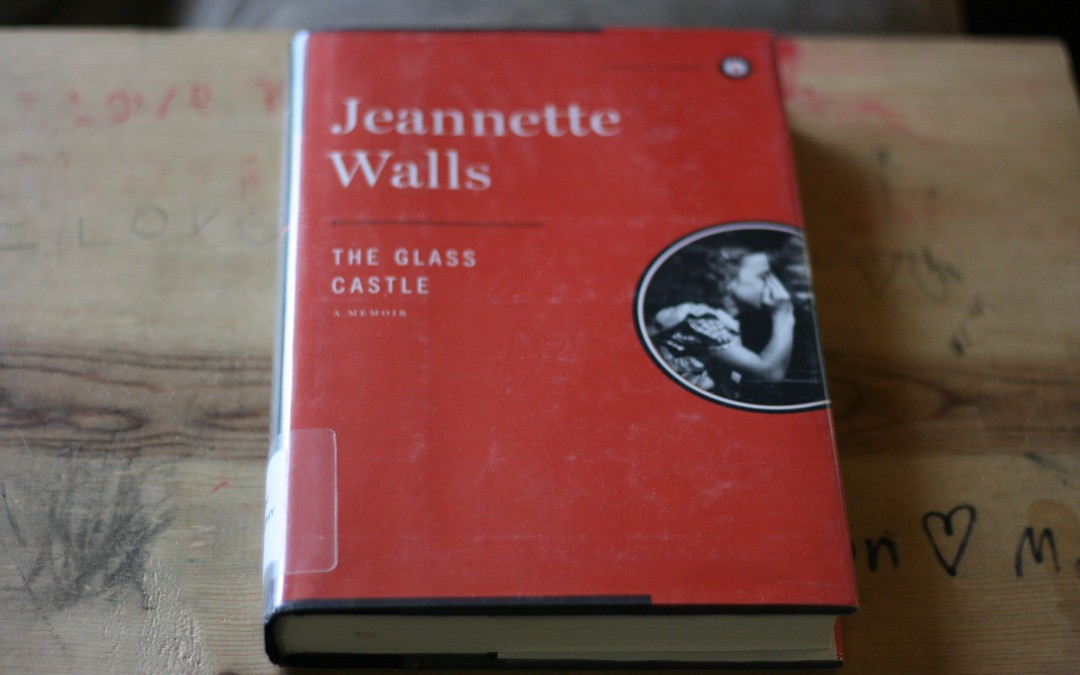

Today I’d like to share with you two heartfelt memoirs that will make you feel every emotion humanly possible.

The Glass Castle, by Jeannette Walls is sort of a classic in the memoir genre. It’s highly regarded on every list of best memoirs to read. I had never read it myself, but once I did, I understood completely why it’s there.

This story was incredibly heartbreaking. Walls and her brother and sisters grew up devastatingly poor and were the children of neglectful parents. They didn’t really know any of that at the time, of course, not until they were older, but they had hints of it in their childhood. What stood out most about this fact and about the book in general was that Walls told the whole, brutal truth about her parents’ inability to care for her and her siblings, but she did it all in love. No matter how awful the situation was, she approached it with grace. This is the power of writing a memoir years removed from the experience.

Rex and Rose Mary Walls moved their children around, always chasing the next unlikely dream Rex had in his heart. Rose Mary often left the kids to themselves while she painted, chasing her own unlikely dream. Sometimes the family didn’t have anything to eat but butter, because neither parent worked. Rex was a brilliant man with a brilliant imagination, and he mostly made life fun, when he wasn’t drunk. Rose Mary could not bear the responsibility of providing for her family, and because Rex was always chasing his next big dream, the family didn’t often have money for anything. But Rex and Rose Mary were also too proud to get government help. It was a very tragic situation for the children.

At times this book was so very sad—because while you felt angry at the parents for not really taking responsibility the way they should have, it was also obvious how much they loved their children—especially Rex.

Walls has a poetic style of writing that made the story that much more enjoyable. I was never once bored, because she has such a gift for capturing a moment and creating three-dimensional characters that you could not help but love, even while you hated. It was excruciating to read about the poverty they lived through with such parents. I was poor as a child, but I was not that poor.

What I liked most about this book is that Walls also showed how she and her siblings escaped the toxic situation with her parents. They broke free of their parents’ grip, which raised the question: would they have been so persistent and determined if they hadn’t lived through these circumstances? It’s impossible to tell.

Here’s one of my favorite quotes from The Glass Castle, which showcases the kind of poverty Walls lived in:

“We called the kitchen the loose-juice room, because on the rare occasions that we had paid the electricity bill and had power, we’d get a wicked electric shock if we touched any damp or metallic surface in the room. The first time I got zapped, it knocked my breath out and left me twitching on the floor. We quickly learned that whenever we ventured into the kitchen, we needed to wrap our hands in the driest socks or rags we could find. If we got a shock, we’d announce it to everyone else, sort of like giving a weather report. “Big jolt from touching the stove today,” we’d say. “Wear extra rags.”

The second memoir I recently finished was A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy, by Sue Klebold. If you don’t recognize this name, Klebod is the mother of Columbine shooter Dylan Klebold. The Columbine shooting was the most violent school shooting in the history of the United States and happened on April 20, 1999 in Littleton, Colorado.

This book was only recently published, and it’s been on my list for a while. This is the first time Klebold has broken her silence about her son, at least in written form, and this book was a beautiful offering to the public.

I truly cannot say enough about it. In A Mother’s Reckoning, Klebold takes readers by the hand and walks them through what life was like with Dylan. It might surprise you to know that he was mostly a regular kid. He didn’t get in much trouble, didn’t cause much trouble, didn’t require much in the ways of discipline and redirection. In the days after the Columbine shooting, there was a lot reported about Klebold and her husband—how they’d been terrible parents, how Dylan must have been abused because that’s the only reason someone would want to go on a killing spree, how this could never happen to good parents. But Klebold’s book proves that this could happen to any of us.

The Klebolds were a family that sat around a dinner table and talked about their days. I do this every day with my family. They supported each other in their school and work functions. My family does this, too. They loved each other. Of course every family does.

Klebold had no idea, until after the tragedy, that her son was severely depressed. So her book is mostly an entreaty for parents—to look hard for the signs of depression. To pay attention. To find the places where our children are hurting and try to heal them with professional help, if need be.

A Mother’s Reckoning was a love poem, a memoir, a valuable offering to a public that has wondered about what went wrong in the homes of Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris. Klebold shares candidly and honestly, and nothing she writes is without grace and honor and love. She does not make excuses for her son, but she writes so that she can raise awareness about brain health disorders and equip parents to recognize it, accept it and do something about it. This is a book I think every parent should read, without exception.

I hope you’ve enjoyed these book recommendations. Be sure to visit my recommendation page if you’re interested in seeing some of my best book recommendations. If you have any books you recently read that you think I’d enjoy, don’t hesitate to get in touch. And, if you’re looking for some new books to read, stop by my starter library, where you can get a handful of my books for free.

*The books mentioned above have affiliate links attached to them, which means I’ll get a small kick-back if you click on them and purchase. But I only recommend books I enjoy reading myself. Actually, I don’t even talk about books I didn’t enjoy. I’d rather forget I ever wasted time reading them.

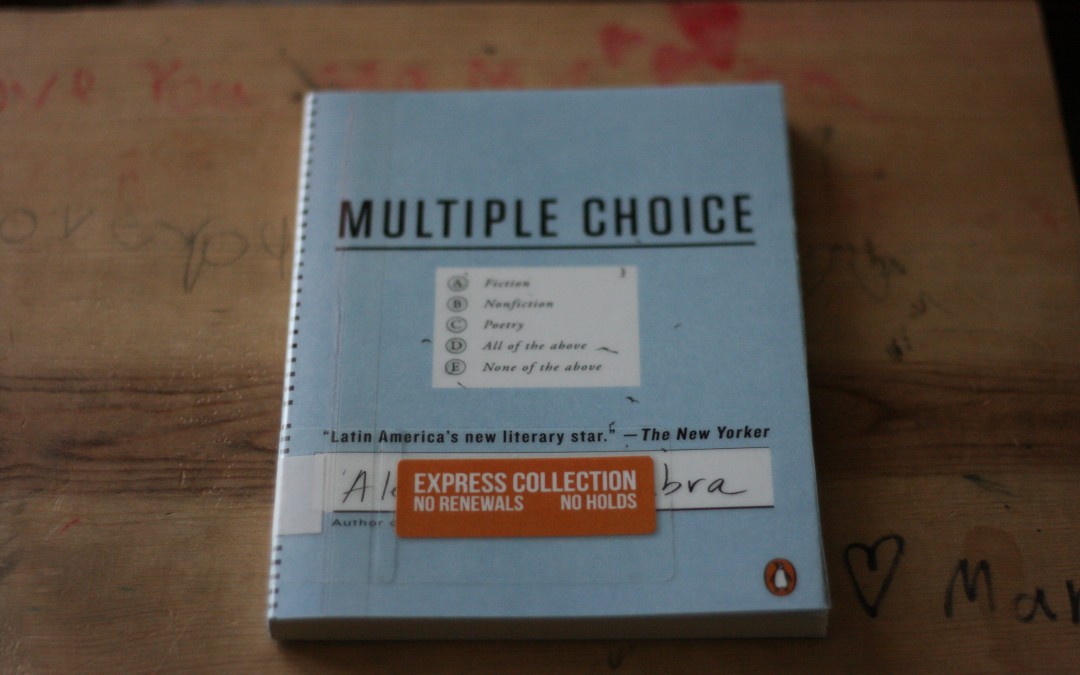

by Rachel Toalson | Books

First, I have to say, I read poetry every single day. I’m a firm believer in how poetry can help its readers increase their grasp of language and metaphor and the simplicity of life made complex. I love reading poetry, and recently I picked up Multiple Choice, by Alejandro Zambra.

Zambra is a Latin American poet who pushes the poetry form in a very interesting way. His entire book is structured like a standardized test. I know this sounds weird, but it was really, really interesting. He broke the book down into several sections, including a strictly multiple choice portion, a comparison portion, and a portion with short narrative passages and multiple choice questions about those passages. This was probably the most interesting poetry book I’ve read to date.

What his form did for readers is it gave them an opportunity to participate in the meaning of the poem. Poets usually do this anyway—they write a poem, we have the privilege of interpreting it through our life’s lens. But Zambra did this even more intentionally by asking readers questions and giving them choices for how the resulting poem would be structured. I found this fascinating.

Zambra is funny, introspective, political, mysterious and poignant. He writes about family and love and authoritarian living, and, at the heart of Multiple Choice, he explores the difference between thinking for ourselves and walking the world as trained, obedient people. I loved the creativity of his form, the flow of his narrative passages and the limitless possibilities he gave me to interpret his poems. It was a poetry book well worth reading.

Robin Coste Lewis’s poetry debut, Voyage of the Sable Venus: and Other Poems, won the National Book Award for poetry. Her book is a meditation on the black female and was riveting and beautiful in its own way.

Lewis bookended her title poem with autobiographical poems that examined what it was like living in the world as a black female. Her middle section was a log of titles of artwork from ancient times to the present time that featured or commented on the black female. She used those titles to craft a long, drawn out collection of free verse poems that included lines like “Black female holding a bowl,” “Black female kneeling by a master” and others. It was an interesting look at the way the black female has been portrayed in historical times up to the present.

Lewis explores stereotypes, the construction of our histories and our selves, and the impact of art on race and relationship. Voyage of the Sable Venus was a beautiful offering to the world of poetry.

I hope you enjoyed these book recommendations. Be sure to pick up a free book from my starter library and visit my recommends page to see some of my favorite books. If you have any books you recently read that you think I’d enjoy, contact me. I always enjoy adding to my list. Even if I never get through it all.