by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Floating about aimlessly in the world of writer and author is not an effective way to build a career. One cannot simply say, “Whatever happens will happen,” because then nothing will, in fact, happen.

I know. I used to be that writer.

I thought making goals and holding myself to them meant that I absolutely had to do them, that there was no room for steering in a different direction if I so decided I needed a different focus. I thought that marking down “eight rough draft manuscripts” on a year’s calendar meant I absolutely had to do them or I was a failure. Goals felt like a cage rather than a wide open door.

And then I realized that goals are not set-in-stone things but more guideposts-along-the-road things. Which meant that if I didn’t make goals at all, I was not going anywhere. I existed like that for a while, blogging on a book that I’ve released recently, but I wasn’t really going anywhere. I didn’t have any direction. I didn’t have clear-cut goals. I didn’t have much vision beyond this one small thing.

So now, every year, I spend the last week of the old year and the first week of the new year making a plan, listing out all my goals, piecing together my time, because as a parent writer there is a limited amount of it. I estimate how long it will take me to do certain projects, and I map out the year. I have a direction, and that doesn’t mean my direction can’t change somewhere along the way, but it means that I have a framework for what my year will look like. How I move around within that framework is entirely up to me.

I make word count goals. I make novel goals. I make goals for everything I need to learn (and there are so many things), and I make goals for how many books I’ll read and what types of books I’ll read and what each month will hopefully teach me. I make goals for how I’d like to see my business grow and what sorts of things I’d like to streamline and how I can possibly reach all of my goals. I set goals for goals. I have direction. I have a plan. I have the velocity that will move my career forward.

Sometimes it can feel like making these goals will only set us up for disappointment if we can’t, for some reason or another, meet them by the year’s end. I like to shoot high in my goals (I overshot my last book release by about 20 copies—it didn’t do as well as I had hoped it would), but that doesn’t mean I’ve failed if I don’t actually meet them. Any progress toward goals is a win. If we are constantly working toward our goals, we can’t help but move forward in our career.

If we want to move forward in our writing career, we’re going to have to lay out some goals. Because goals give us direction, which gives us focus.

A writer without focus will be lost in the great, fathomless sea of What Should I Write.

What goals do for us as writers is they help us analyze where it is we want to go in our writing career. When we say we want to deliver eight rough draft manuscripts at the end of a year, we know that we’re going to have to schedule out the time it will take to get them done. If we only say that we’ll write however many rough drafts we may get around to, we’re probably not going to write any of them.

Making goals concrete can help us plan out our year and schedule deadlines so that we have the best chance of achieving all it is we want to achieve. Each goal can then have tangible steps, and we can break them down as far as we want to (this might be harder for the not-planners among us), with action steps for each month and each week and each day.

If goals change halfway through the year because another opportunity plops in our lap, that’s okay. There’s nothing written in stone that says we have to do what we originally said we’d do. We can massage our goals at any point, if we find it takes us longer to write those rough drafts than we originally planned, or if another book comes knocking, insisting that this is the right time for it to be written. Those things happen. What goals do is provide a framework of intention around our year. We are less likely to drift off-shore if we have a framework for our year.

In addition to goals every year, I choose a word for my business. This has its roots in my family’s practice of choosing a word that provides the framework for our year (this year’s family word is Play. Such a great one. We are even going to explore how to play in our work.).

My business word for this year is actually two words: Forward motion.

This phrase means a lot to me. For a while I’ve been feeling like I’m standing still, like there is nothing much happening, like I’ve done all I can and I can do nothing more, and now I have to wait for people to come and get me. But that’s not really true. There are thousands of little tweaks I can make to my content and my web pages and my blog that would make all of them more effective, and this year that’s what I’m going to be working on in between my writing times. I’ve also got a manuscript out with an agent that’s been out with her for months now, and I’m going to get it back out there in the next few weeks. I have more manuscripts to pitch, and I’m ready to move forward in the traditional publishing game. Not only that, but I’ll be self-publishing some fiction I’ve been working on for a year now.

Regardless of all that, everything I do this year that is geared toward my business will be analyzed through those words: Forward motion. If I don’t think a particular activity is going to result in forward motion, then it’s not going to make my list of things to do.

There are so many things we can do out there as writers. There are social media platforms we need to make appearances on, and there are responsibilities we have for blogging, and we can get caught up in it all. And then we find that we’ve gotten so far from the time we had to write that we have absolutely nothing left. I don’t want to be there. I want to be moving forward, not standing still.

My top three learning goals are:

1. Photography—so I can offer better pictures of my own on all of my blog platforms and social media pages.

2. Using social media well—this has been a goal for a while. I’ve slowly been making progress.

3. Graphic design basics—I rely a whole lot on my husband for graphic design, and he’s a busy man. So I’d like to learn more about the basics so I can do social media posts that are graphically pleasing. I will NOT, however, be attempting book cover design. Ever.

My biggest goal this year is to grow my business without sacrificing my family.

Other goals include:

Turning all rough draft manuscripts into final drafts (there are eight roughs right now)

Sending at least 10 manuscripts out to agents this year

Doing slight revisions on final manuscripts (there are three finals right now that need slight work)

Writing rough drafts for nine manuscripts

Turning three blog collections into books

Releasing the first season of Fairendale (kid-lit fantasy)

Releasing a free brainstorming course for This Writer Life

Starting a weekly humor show for Crash Test Parents

Writing a 365 days of poetry book

I don’t know if I’ll get around to every single one of these goals, but everything I do will be done with these goals in mind.

If you’re struggling with making your own business goals for your writing career, here are some suggestions to get you started.

1. Decide what it is you want to do most in your career this year.

Do you want to write books? Learn more about something? Publish a book? In order to start making tangible goals, you first have to know what it is you want to do in the first place. List all the things you want to do, and know that you probably won’t be able to get to them all. Rank them in order of importance and then build a plan around them.

2. Pick between one and three things you’d like to learn.

One of the best things we can do for our writing career is to learn something new. It can be about the craft of writing. It can be about writing headlines or effective blogs. It can be about the business of writing or the psychology of influencing people or how to brand yourself. It can be learning more about social media and how to have an effective presence on your handles. There is always an abundance of new things we can learn if we’re intentional about them.

3. Adjust your schedule according to what your top goals are.

I would suggest only having between three and four overarching goals. I have several more than that because I’m an overachiever, but that’s not really ideal. (You can also increase the number of goals as you get to know yourself. I’ve been writing full-time now for a year, so I know what my weekly production is like. That helps me make even more specific goals.) On the other hand, sometimes having a goal that seems way out there in the realm of impossibility is just enough motivation to help us almost make it. Don’t be afraid of large, seemingly impossible goals. If we write it down, we’re more likely to reach it.

4. Share your goals with someone else.

One of the most helpful things we can do for ourselves when we are setting goals is to share them with someone else. It creates accountability, and some of us need a whole lot of accountability. My husband and I always talk about our business goals, not only because we work really closely together but also because it helps having a spouse on the other end of it. We can ask each other daily or weekly about our goals, and we can see how far we have to get there or how close we actually are. Not to mention, it boosts our confidence to have a person we love who is interested and invested in what we’re doing.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

That internal editor can be a big problem.

In November, I participated in NaNoWriMo for the first time, and I was so excited about the possibility of writing a novel in one sitting. Or maybe a few sittings.

I write pretty fast already, and I’m fortunate to have much more time to write than I used to have, but I still have to sandwich my writing around different points of time during the day, and I knew that I would have to use my time wisely in order to finish the book. I had a Sabbath week scheduled in the month of November, so my goal was to finish the story by Nov. 15 and be done with it, and then maybe even work on another novel the week after so I could finish the crime thriller I’m working on, too.

And then I started the NaNoWriMo book, and I already had everything completely brainstormed and mapped out, because that’s just the way I work best, and suddenly, after I was well into the flow and entering the world with my characters, my internal editor came waltzing in and yelling, “THIS IS BAD. OH MY GOSH, THIS IS SO BAD. IT’S A TRAIN WRECK. NO ONE IS GOING TO READ THIS. NO ONE IS GOING TO WANT TO READ THIS. YOU SHOULD JUST GIVE UP. YOU ARE NO WRITER.”

And then that little voice morphed into the voice of my creative writing teacher from college, a pompous man who didn’t like me because he thought I was too “melodramatic” (the same thing my father had called me once upon a time). “THESE CHARACTERS ARE TERRIBLE,” he said. “NO ONE IS EVER GOING TO WANT TO READ THIS. YOU SHOULD JUST GIVE UP. YOU ARE NO WRITER. YOU WILL NEVER BE A WRITER.”

It’s crazy how quickly it can happen, and a whole writing session is hijacked by an imaginary person.

It wasn’t really hijacked for me, because I’m used to these voices coming around. And I’ve trained myself in something that is guaranteed to help you write faster and smarter, and when you’re a parent writer who’s trying to write in the margins, like I did for years, this will make all he difference in the world:

You have to silence the inner critic.

The way to do it is through practice, ignoring the inner critic when it doesn’t matter and listening to it when it does.

Wait. Listening to it?

Here’s the thing: The inner critic has NOTHING valuable to say to you in the first draft of a story. That first draft is just for getting the story out. The second draft is for making it all pretty and neat. (Or maybe a third or fourth draft, if it takes you a few.)

But sometimes the inner critic can be helpful. Oftentimes it’s not, but sometimes, in the revision process, it can have some good things to say if we’re willing to listen. Sometimes what it says about a character feeling two-dimensional means we need to do some revision work there. Sometimes when it says our plot is a little thin we can take another look and add some higher stakes.

But we shouldn’t ever listen to the critic when we’re in the first draft stage. We have to say, instead, “Leave me be.”

The best way to do that is to keep practicing, to keep writing, to keep setting a story down just as fast as we possibly can, because what also happens to this inner critic is that the faster we’re writing, the more chance we’ll have of outrunning it. (This means my first draft is usually full of grammar and punctuation mistakes, because I’m just trying to write as fast as I can.)

The inner critic usually comes to see me in the very beginning when I’m unsure, or when I’m trying to do something quickly, when I’m fully focused and he tries to steal that focus. I don’t like to play his game, because it’s just not helpful at this point.

Sometimes that inner critic can sound like old teachers or people who didn’t believe in us—or don’t believe in us still—and sometimes they sound a whole lot like ourselves.

The abuse mine was hurling sounded a little like this:

You are not equipped to write this story. It’s too big for you.

You really think you can get into the mindset of a boy? These characters will be completely hollow.

What do you know about autism?

What do you know of little boys? (Yeah, sometimes that voice can say some pretty ridiculous things.)

Who do you think you are?

That last one. It’s a killer. Because who do we think we are? Did we really think we were writers? Did we really think we could craft a story as big as this one? Did we really think people would care?

Well, yes we are. Yes, we can. Yes, they will.

Our first draft is what Anne Lamott calls a “shitty first draft.” We’ll use subsequent drafts to shape it into something good and beautiful, and WE HAVE NO PRESSURE FOR THE FIRST DRAFT.

No pressure. Just write. Write it all down without considering any of it.

And after the writing is done, listen.

Here are some ways to silence the internal editor:

1. Set a timer for 15 minutes. Do a writing sprint.

When we’re writing fast, we don’t have to worry about the internal editor, because the thing about writing fast is that it’s just a partnership between our fingers, our brains and the story. Our internal editors can’t possibly keep up with us once we get rolling, because the faster we write, the more imperfect our story will be, and the more we’re okay with that, the softer that voice will grow. Because what the internal editor really wants is perfection. And we’re never going to get that in the first draft. I was just telling someone the other day that I’ll find all kinds of silly mistakes in my first drafts. Things like the wrong use of their or there (I made a near-perfect score on my college GSP, a grammar, spelling and punctuation test required for a degree in journalism.).

2. Try, try and try again.

We have to keep trying, no matter how loud that voice gets. We have to keep practicing. Nothing gets easier without practice, and the same is true for silencing the internal editor. If we’re not going to practice defying his words, then we’re never going to get any better. If we’re not going to try to write anyway, then this editor will plague us always.

3. Have a plan.

Sometimes it helps to have a plan for the story, even if you know some things will change in the actual writing of it. Sometimes I sit down to write essays and it just pours out of me, and I don’t really need a plan. Sometimes I have to go by my plan or I feel like I have nothing valuable to say. Don’t be afraid to make a plan. Just because we make a plan doesn’t mean we are bound by it. We can deviate as much as we want. But sometimes the plan can silence an internal editor, because even if this one scene isn’t all that great, we just have to remember the end to know that it’s all going to turn out okay.

4. Remember that the internal editor will always try to come around.

It’s not that practice makes the internal editor go away. It’s just that the more we ignore his voice, the softer that voice gets. And that’s what helps us in the end. Because the less effective he will be, the less he will try to be effective. We will get better at ignoring him and outrunning him, but every now and then, perhaps when we’re tackling something we’ve never tackled before, we can be sure that he’ll come back around to plague us, and then we’ll have to figure it all out again. But it does get easier every time.

5. Let go of the need to produce perfect art on the first try.

On any try, really. Because we will always find something we could improve about our manuscript, and if we’re just waiting for ourselves to come out with that perfect product, then we are going to be waiting forever. You should see some of my first drafts. I keep all of my journals, but someone someday is going to find them, when I’m long gone, and they’re going to be like, Wow. This is really bad. But I still keep them around, because they’re helpful for assessing how far I’ve come in my career.

There is value in imperfection. The internal editor likes to tell us there isn’t, but he’s lying. Free yourself from perfection, and you free yourself to write.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

A few days last week I felt really invisible. My stuff wasn’t really getting shared, and people weren’t all that excited about visiting my site and reading the words I shaped into stories every week, and sometimes, when we feel invisible, we can forget all the value that lives in our writing. Because it’s not necessary, not like business tools or parenting techniques or “7 meals to cook in 15 minutes.” It’s art.

And then I started going back through some of the blogs I wrote last year, which I’m turning into a book, and I texted my husband. “This stuff is really good,” I wrote. “Even better than I remember” (writers don’t say that about everything).

We have a hard time seeing what value lies in our writing, because it’s artistic and it’s entertaining and it’s a fun story, not an I’ll-die-if-I-don’t-get-this kind of thing. But let’s just think about this for a minute. What kind of life is a life without art? What kind of world is a world without the beauty of words turned stories? What kind of society would this be without poetry?

It’s not an easy seeing. I know. I’ve been launching pieces of myself out into the literary world, and it’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever done (besides raising children), because it means I have to toot my own horn a little. I have to tell people there’s value in my work. I have to be its champion, and you know what? I would MUCH RATHER have someone else do that. I’d much rather have someone else tell the world that my products have value. I’d rather have someone else claim that lives will be better for my words.

But something I’ve had to come to understand is that there is value in what I do. There is value in the words I spend twenty-five hours on every single week. There is value in the books I write and compile and then release. There is value in my offerings, in my talent, in my entertainment. My art fills a hole in the world, and it may not be a hole we can see surely and point to without question, but it’s a hole that is there all the same, and people are changed when art fills in their holes.

It doesn’t matter if we don’t have a five-step takeaway for every product we launch into the world. It just matters that we are looking for holes and we are filling them.

There isn’t a whole lot out there about selling entertainment and how to do it, because most of what’s written from the business perspective is about selling value, and when we’re in the entertainment realm with our parenting humor blog or our thriller novels or our kid-lit poems, the line between value and non value is a little blurred to those in the business world. They don’t often see the value in a person, bent nearly to breaking, reading the words of another who has been broken and finding strength and courage enough to say, “Me too. Let’s carry on together.” They don’t often see the value in words that grant hope and peace. They don’t often see the value in abstract things like poetry and music and stories.

But that doesn’t mean that we can’t take business principles and mold them to fit our entertainment offerings so that we can become even better at what we do. The first way I did that was by finding my “value propositions” for my different platforms.

A value proposition is a short phrase that states what value you bring to the world. It can be easier to craft a value proposition when we’re doing things like teaching writing or selling courses or meeting a real, tangible need in the writer world. We’re going to have to work a little harder when we’re not.

One of the holes I most like to fill with my nonfiction is the hole that says “I am alone.” I write honestly about life with six boys, and I turn it into a humorous, lighthearted offering on my parenting humor blog. I write about serious issues like anxiety and body image and depression and loss, and I help people feel less alone in their struggles. People find solidarity, and they are encouraged, and this is a valuable thing.

So, in crafting our value proposition, we have to think about what our art will do for the world. Will it encourage? Will it entertain? Will it offer humor to a dark world? Will it tell the whole truth?

Without a value proposition, we can get lost in weeks of invisibility. No one seems to care what we’re doing, and we start to wonder why we’re doing it. But value propositions can remind us that there really is a reason.

4 Steps to Creating Your Own Value Proposition

1. Define who you are.

Are you a storyteller? Are you a truth teller? Are you a fellow traveler? A sage? A muse? What makes you unique? Come up with who you are to your “tribe,” and you’re well on your way.

2. Determine who your audience is.

You’ll hear it all over the place, and it’s true: The wider your audience, the less influence you have. If we can narrow things down a little, we’ll be able to reach a wider audience, which doesn’t really make sense in the math of it, but it does, a little, in the marketing sense of it. Lots of people say they’re for everyone. Not a lot of people are saying they’re writing a humor parenting column for moms who only have boys. Niching down is scary. I know. It was for me. But sometimes it’s the best thing we can do. I felt much more focused when I niched down This Writer Life to be parents who are time starved and still trying to pursue a writing career.

Who is going to listen to you? Who do you most want to help. If you say, “Everyone,” you will help no one.

3. Figure out what you will help people do.

This could be anything as abstract as providing a new insight to readers or invoking a laugh to something more tangible, like learning how to use WordPress or self publish a blog post or write effective copy. Sometimes it’s hard to see what we will help people do when we’re on the entertainment, novel-writing side of it, but if we look closely enough, it’s possible. There is something unique that we bring to this world, and no one else can do it like we can. People can buy transformation they hope will happen in their life just as surely as they can buy a course on writing faster.

What unique thing do you have to offer in the world of entertainment?

4. Put it all together.

My value propositions for my platforms look like this:

Fiction writing/Wing Chair Musings blog:

I am a storyteller. I help readers who are curious, open-minded and seeking authenticity grasp new insights on life, love and family so they can remember and embrace the truth that already lives inside them.

Crash Test Parents (humor blog):

I am a mom of six boys. I help boy moms understand that the best way to survive life with boys is with a sense of humor, so that they can fully embrace the wildlings they’ve been given.

This Writer Life:

I am a parent writer. I provide productivity, publishing and writing advice to time-starved parents so that they can pursue a writing career in the margins of their parent life.

By far, the easiest one of those to write was This Writer Life, because it has more tangible benefits. But entertainment can have value propositions, too, and it’s worth it to do this work.

These aren’t perfect value propositions. They will probably shift and change over the years. But they’re a good start.We can do a whole lot with a good start.

Value propositions help you get clear on who you want to be and what you need to do to get there. Put yours together, and watch your focus completely change.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life, This Writer Life Featured

Some people in the writing world think it’s hardest to get started. And it’s true that it’s hard to get started. But it’s also true that it’s hard to stay started, especially if you’re a parent.

I go through these cycles where I think about how my boys are just growing up so fast. Husband and I just moved the baby, who is nine months old, to his crib, and he’s our last one, so we sat in our bed getting all teary-eyed, because he’s the last baby we will ever have in our room, forever, and that feels significant and sad. And of course then I started thinking about how I’m using so many moments when I’m with the boys to work on email lists and to edit submissions and to edit other books, and maybe I should be spending that time playing and looking into their eyes and just enjoying who they are today without tomorrow and business and expectations stealing them from me.

When we’re parents, we can start to feel some guilt for pursuing a dream in all the spaces, because shouldn’t the spaces be reserved for our children?

But what I circle back to every time these thoughts start haunting me is that life and a dream are interconnected. When we are living life from the pursuit of our dream, we are living a real, authentic life. When we are pursuing a dream in the spaces of our lives, whatever that may look like right now, we are serving our dream. They both inform each other, and they’re both tangled around each other. They cannot be separated.

If I were to quit pursuing my writing dream tomorrow, I would not be a pleasant person to live with. I write to make my world clear, to preserve my most sacred memories, to make sense of my frustrating and joyful and disheartening and victorious experiences. If I didn’t have that outlet, my family—my children—would know. In fact, they did, for several years before I made my dream-pursuit a real possibility after I grew tired of watching it wave at me as it flew on by. I’m a much different person when I’m pursuing my creative interests. I’m a better wife, a more patient mother, a more whole person because of my writing.

Our writing enriches our lives. Our lives enrich our writing.

So we can talk about balance all day long, but what it really comes down to is integration. How can we integrate our creative pursuits with our lives? How can we integrate our lives with our creative pursuits?

How can we become a more whole person?

You’re the only one who can answer those questions, because it looks so very differently for all of us. But it’s worth answering them. For our families and for us.

Here are some ways we can find integration in our art and our lives:

1. Create with our families.

Maybe this looks like sitting around a table every night and writing in journals together. Maybe it looks like incorporating storytelling into our everyday life. Maybe it looks like brainstorming with children when we’re stuck on a plot line, because other people (especially children) have really great ideas, if we’re willing to dig down to those diamonds and really listen. Maybe it looks like writing a picture book together.

This summer my boys and I wrote pictures books together. My boys are still working on the pictures, but, eventually, they will finish, and we will publish, and they will have books published at the ages of 8, 6 and 5. That’s a pretty powerful experience for children—to know that their art matters.

Our family life can become our dream-pursuit life, too, even if it’s just in a casual way for now and someday becomes something more serious.

2. Find the spaces and give some of them (not all of them) to dream pursuit.

Our lives are better lived when we are pursuing a dream in some of the spaces. Children need some of our space, of course, because they are growing and we are their parents, and we will want to give them time and attention, since we know that our writing is richer for the life experiences we collect on a daily basis. But we cannot give every space to our regular life (especially things like laundry and dishes and cleaning bathrooms, since procrastination often lives in those things), just like we cannot give every space to our dreams. When I worked full-time and decided to write a book, my house didn’t get cleaned for a whole year. I gave myself permission to exist in a dirty (but not unsanitary) house, because the dream was waiting to be pursued.

3. Talk about our dreams with the people who share our lives.

Kids are great dreamers, and it’s worthwhile to talk to them about our dreams. Sometimes they are incredibly generous and will come up with things like, “I’ll take care of my brothers while we’re watching a movie if you want to work on a project,” like my 8-year-old did the other day. It was generous of him to offer his time to watch his brothers (even if I didn’t take him up on it—because he’s only 8), but as they get older, they get to enter into this dream with us and try to figure out ways they can help us shape it into the spaces.

If our kids never know what we’re trying to do, they will never know how they can help. And if they never know we’re dreaming in the first place, they will never know it’s okay to have their own dreams. We talk about our dreams regularly with our children, because it’s so important to our family life. We do Dream Sessions once a quarter to make sure our children know what dreams are and how important they are to a life.

4. Understand that there are seasons.

Sometimes there are season where life takes all the spaces. And sometimes there are seasons when writing demands all the spaces. Right now I’m working on deadline to finish a memoir by the end of the year, which means that I am working diligently during Family Movie Night to finish it. But there’s also an end date to that arrangement. The arrangement only stands until the memoir is finished. After that, I will be able to sit beside my boys and watch a movie with them.

There was a season, about a year ago, when our oldest was struggling with some anxiety issues, and I found myself unable and unwilling to write until we could sort through things with him and get to the very bottom of it, because my boy needed me. And then I had to write to sort out all my own feelings about what had happened. And then I had to spend more time with him. And then I had to write again.

So the seasons come and go. As long as we keep in mind that they are not forever, that this time we have or don’t have to create is not forever, we will be able to move and flow with the seasons of life.

5. Let go of the guilt.

Easier said than done, I know. Especially in the beginning, we will feel a lot of guilt about how we’re trying to pursue writing when our children are still waiting to be raised. Is it selfish? Is it ridiculous? Is it irresponsible?

No. We are writing to become whole, and this ALWAYS serves our children. We are doing what is best for all of us. And that’s worthy. It’s enough.

Guilt has no place here.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Alright. So we’ve gotten through the resistance of selling ourselves, I’ve taught you what I learned about product launches from doing my own launch, and last week I shared how to get better at each progressive book launch. Today I’m going to give you a handy list of everything we need for an effective book launch. You’ll just have to fill in the pieces.

But a quick word first: Some of us think, when we have that “one, big book idea” that that’s it. We’re done. We launched out book and that’s all we’ll ever need to do.

False. If we’re interested in making writing a business, we will have to immediately pick up a pen and go at it again. And again. And again.

You know the best way to make it as a parent writer? Keep writing. Book after book after book. Because one will probably never be enough. I’m just telling the truth.

But this is good news, too. Because chances are, not only do we have more book ideas, but with each book we put together we’ll also be able to experiment with our launches until we get it exactly right for us and our audience.

Now that I got that out of the way, I wanted to share with you a nifty list for what I’ve included with my second launch, using what I learned from the first launch. This list will continue to evolve and change, but, for now, here’s what I believe is needed for an effective launch.

There are many different aspects of launching a product. There’s the initial getting-information-out, which is essentially creating a buzz about the product. The prelaunch time. The earlier this can start, the better. Months in advance would be great. I usually don’t plan well enough for that. This second launch had a landing page about six weeks before the project was scheduled to release.

Even if our projects won’t be done for a couple of months or a year, the sooner we can get a landing page up and start generating interest in it, the better our launch will end up going. What I’ve learned most from my process is that even when I’m in the rough draft writing stage, I need to be thinking about how I’ll be marketing my book. With so much out on the market, it’s harder and harder to stand apart, so it’s important to have that plan already in place.

So, in case you missed it, the first step to an effective book launch is a landing page.

Elements of a good landing page:

- A section with the book cover on display, along with a great product description. I hate writing product descriptions, mostly because it’s like “selling” the book that I wrote, but this is hugely important for drawing people in. Product descriptions are some of the most important tools for selling a book.

- A video that details, in a general way, what the project is and why you decided to write it. For my particular project, I decided to include little snippets of my family, because the project was one about living from family values. For fiction projects, you can document the writing process (or if it’s too late and you already have it written, you can stage it).

- Good copy that tells a story about the project. My landing page included some of the story behind what drove me to write the project (which was a nonfiction book—but I’ll be trying this out with a fiction project in December), what’s included it in and, the most important part, when it will release.

- A section where those interested can sign up for an email notification for when the project releases. This is important. These are the people who will be your primary customers. They’re already interested in the project—enough to sign up for a list where they’ll be emailed once the project is on the market. I chose to incentivize my email notification list with a companion guide about the project. People love having an inside look (for fiction) or some kind of practical application (for nonfiction). My fiction project, which will have a landing page sometime in December, will include a short story “prequel” that will introduce people to some of the characters.

It doesn’t end at the landing pages. Husband, who is a content marketing consultant, detailed out a three-week social media marketing campaign, where I would:

Share a book excerpt on my blog once a week

Post on Facebook and Twitter about the project three times every week.

Week one: The process and behind-the-scenes

Day one: Text

Day two: Picture

Day three: Video

Week Two: Origin story/inspiration behind the project

Day one: Text

Day two: Picture

Day three: Video

Week Three: Who the book is for and how the world will be different because of it.

Day one: Text

Day two: Text

Day three: Video or picture (in our case it was an infographic)

Three days before the book launched, we released three pre-launch videos with the following content (we will probably change this order next time):

Video 1: The story behind why I wrote the series

Video 2: What I hope people will get out of the series

Video 3: A real look inside (in the case of this particular book launch, it was how hard it was to live from our values every single day)

This might look like a lot of work. But here’s the thing: I did all this work once, for a series that will be spanning an entire year. When I do it again in December for my fiction series releasing in March, I will only have to do it once for a project that will span about five years. When we’re writing series, we can get the most out of a thing like a landing page, and when subsequent books release, we can still just point people to the landing page. It might be a lot of work for single books, but the truth is, single books probably need it even more (and also a greater lead time).

If you want to know more about the details of how to do this, visit my latest project landing page or connect with me on Facebook or Twitter. I don’t claim to have it all figured out, but I am actively learning and tweaking my process so that I can launch my books into the marketplace with the greatest momentum possible.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

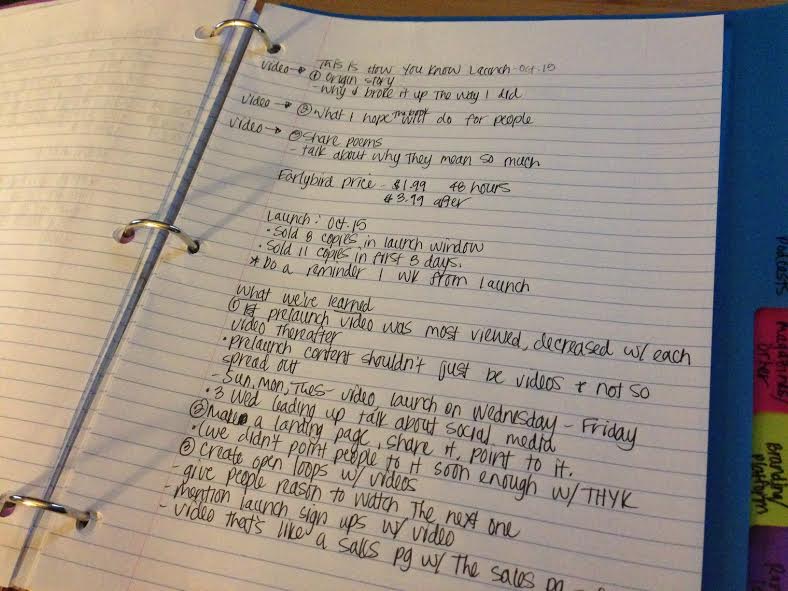

Before I launched my first self-published book, This is How I Know: a book of poetry, I spent hours poring over launch strategy and trying to figure out the best way to go about launching a book of entertainment, because even though writing comes naturally to me, marketing does not. Not even a little bit.

Much of the information out there has to do with launching a product like a course or a book that has a specific takeaway with it, and it isn’t really geared toward entertainment things like fiction or songwriting or something that is more a “want” than a “need” for people (even though, arguably, people need entertainment in their lives or they’re not really lives worth living). So, in a way, I felt like I was crossing into uncharted territory.

That’s what made me want to write down every single strategy we came up with for our book launch—because I knew that I’d be doing it again, and I needed to learn from my mistakes and tweak my process so that every subsequent book release would do better than the last. No one else would do that for me. No one else could tell me exactly what would work, because I was selling entertainment, which has a completely different value proposition than something like a self-help book. People aren’t learning something from my project. They are feeling something. That means I had to invoke emotion.

So I wrote the copy for a landing page and three videos that we used to promote the project, and I made sure that emotion was in every bit of it. And I think it was a pretty good effort—but as I shared in the last post, there were certain things we could have done better.

It’s important that every time we’re doing a product launch, we are analyzing and assessing our efforts and keeping track of what works and what doesn’t, because if we want to build a business out of this writing, we’re going to have to come out with more products. Which means we’re going to have to launch them. Which means we’re going to have to have a solid strategy.

I came into that first launch knowing that it would not be done perfectly. Maybe none of the launches will ever be done perfectly, but the one thing I can guarantee is that every one of them will be better than the last. Because I have come up with an evaluation plan.

It’s funny how we implement things like evaluations into other parts of life. What’s working in this parenting? What’s not working in the way our family eats dinner together? What can we do better.

And yet, when it comes to writing and running a business, we excuse ourselves from it, because it’s “just not for us.” We just want to be writing. We just want to be creating. We just want to use our time wisely.

But the thing is, we’re using our time wisely in evaluation. Not only in evaluation of our stories in the rewriting and editing processes, but also in the evaluation of our strategies behind things like book launches. This is what will monetize our business—and even if we’re doing writing just because we love it (which I hope we’re all doing), if we ever want to succeed as an author, we’re going to have to monetize it. It’s what agents will tell you when you pitch a book. It’s what publishers will tell you before they’ll buy your book. It’s what you have to tell yourself if you’re self publishing.

And the only way to get better at monetizing our art and launching our products is to evaluate and learn from what we have done before and from what others have done.

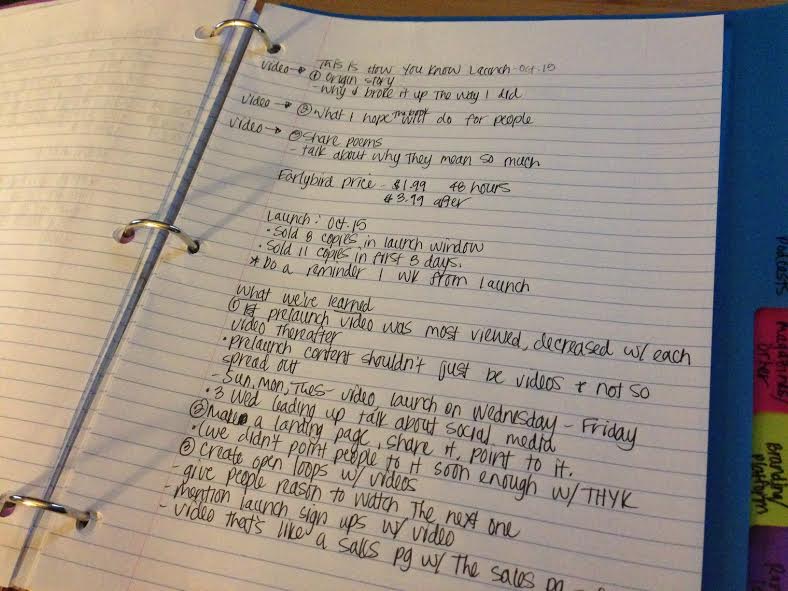

After my book launch was all over and done, Husband, who is a branding consultant and content marketer, and I sat down to analyze what we’d done and what we could do better. I shared a little about that in the last post. And as soon as we finished that, we began to plan the next release, which would happen six weeks later.

Because even though my poetry book only sold about 11 copies, because my audience is still relatively small, and an even smaller percentage of people will actually buy a book, I knew that the best way to keep growing my audience was to keep producing products. Keep writing books. Keep launching them out into the world.

But not without a plan.

Here are some ways you can be learning and refining your launch strategy.

Step 1: Research

Research is necessary for effective launches. There are always things we can improve on, and unless we have a background in marketing and product launches, we’re probably not going to be able to know everything there is to know about how to effectively launch a book into the marketplace. We can learn from people who know much more than we do.

One of the best resources on product launches, in my opinion, is Jeff Walker. He runs the Product Launch Formula, and he’s fantastically generous with his content and offers a paid course for those interested. I have not take the paid course, but as soon as there’s budget for it, I plan to.

Step 2: Assess.

Look with a critical eye on what went well and what didn’t. Unless we’re constantly assessing these things, they’re not just going to jump out at us. It wasn’t until Husband and I sat down and looked at stats and numbers of views for videos that we could figure out what might have gone wrong or exactly right in our strategy. And of course there will be some variables, because sometimes it’s just a bad time of year or a bad day of the week, and there’s not really a way to analyze why, but if we’re experimenting and keeping track of things like stats and response and sales, we can better know where to go from here.

Assess not only stats but also the quality of content you put out about your book. Sometimes there are tiny little things that could be tweaked to have a better result. It’s best to analyze these aspects with someone who isn’t quite as connected to it, because we can often be blind to our own work.

Step 3: Implement/tweak.

Once you’ve assessed what worked and what didn’t work, make a plan for the next launch that will implement and tweak the problem areas. If we’re not constantly improving, we’re either remaining in a static place or moving backward. Analyzing has not purpose if we’re not willing to tweak the places that need improvement.

Step 4: Experiment with the launch.

I try to keep in mind that every launch I do is an experiment. I’m probably never going to have this whole thing figured out. But I do expect to get better and better at it, and, eventually, I’ll develop my own solid strategy that works for me. I don’t know that there can be any formulas, per se, because each book will be individual for its own market, but I can constantly experiment with what works and then assess and tweak and continue doing research that will put me on better footing for the next time.

Step 5: Repeat.

These steps will be repeated again and again and again, as many times as we are laughing projects. And before we know it, we’ll get really, really good at them, so they’ll become more second nature. Before we even start a project, we’ll be thinking about how we might launch it.

These steps will guarantee we get better at every successive book launch.

(Next week I’ll give you my checklist for my upcoming release.)