by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life, This Writer Life Featured

I’ve had some trouble getting a handle on my schedule lately.

Part of it is because my boys are al home for the summer, so the time I normally have to work while they’re in school is virtually nonexistent. I still have large chunks of writing time, because my husband and I trade off kid-watching shifts so both of us can do our creative work, but I haven’t been maximizing the time in the most efficient way.

I write a crazy amount of content for all my blogs every week. Most of the blogging takes a total of three days (or workable hours for those days—which is about four hours a day). That’s a huge amount of time.

But I’ve been breaking up those blog writings into all five days of available work time. Which didn’t seem very efficient.

When we’re parents, we’re not often given huge amounts of time to write, which means we need to do whatever it takes to maximize our time. I didn’t want to just be producing content for my weekly posts. I wanted to also be getting somewhere on a couple of the books I have in the works, and just having four hours at the end of the week was not cutting it.

So I decided to reevaluate my time.

I looked at where I was spending time and what all I was doing each week to see if I could group like things together (like a blog day and a newsletter day and a “pitching stories” day).

And then I tried an experiment.

Here’s a sample of what my schedule looked like:

12:30-1:45 p.m.: Write story roughs

1:45-2 p.m.: Post on social media (platform work)

2-2:30 p.m.: Write Messy Monday post

2:30-3 p.m.: Submit Huff Post blog

3-4 p.m.: Write/schedule This Writer Life blog

4-5 p.m.: Write/schedule Crash Test Parents blog

5-5:30 p.m.: Read.

I had the highest word count I’d ever logged in a week (nearly 25,000 words).

It was much more efficient than my old schedule.

I’m a proponent for working in whatever time you have, even the short bursts, which is what I used to do before my time opened up a little more. I believe we can train ourselves to work in those short bursts and in the margins of time we have as parents.

But when our time does open up, why wouldn’t we wan to reevaluate and see if we could streamline our time so it’s most efficient for the season we’re in?

Schedules are critically important to write, because if we don’t have writing time scheduled, chances are we aren’t going to get it done. So much can come in the way of our writing—kids who need something that’s not necessary right this minute, other people asking us to do things for them (especially if we work from home when a spouse is at home), phone calls or social media that could wait until later, when we’re not so pressed for time.

My old schedule also left little room for margin. So when something unexpected did happen—a boy interrupting and I’d get thrown off what I was saying in the final draft of an essay—I would run over the scheduled time for that particular writing. And because everything was lined back-to-back (to ensure the most efficient use of time), ending a task late meant I would start the next task late.

So I worked in some margin. (Generally it doesn’t take me a whole hour to write an essay. Maybe 50 minutes, which left an extra 10 minutes for the unexpected.)

When we find a schedule we like, reevaluation is not the first thing we think about doing. But it’s a practice we should work in, because every season of life changes. Our schedules need to be fluid to keep up with those ever-changing seasons.

When my boys go back to school, my time will feel a little more like mine, again, and the schedule will shift accordingly.

Here are some questions we can ask ourselves in the evaluating of our schedules:

1. Am I wasting any time?

Sometimes we don’t like to admit to this one. I know I don’t. But the truth is, sometimes a story feels really hard for now. Sometimes I need to take it back to the drawing board or let it sit. Evaluating those things help us assess where we might be pushing something that doesn’t want to be pushed just yet.

Other places we waste our time tends to be social media or the Internet. My husband likes to watch YouTube videos. The problem is, one video leads to another, and pretty soon you’ve wasted half an hour just watching videos.

The way I combat this tendency is to schedule “break” time and set a timer. The rest of the time, I focus only on work and close out all my Internet tabs.

My time is too precious to spend it clicking the next most interesting thing that comes along.

2. Is what I’m doing working?

This was the question I had to ask when I noticed how spread out my weekly blogs were. An hour here, an hour there, and I didn’t have any large chunks where I could just be writing my fiction stories. So I grouped all those blogs together, and now I have large chunks for fiction writing. I get to write my way into a state of flow and just stay there a while.

The thought behind my original disjointed schedule was that I didn’t want to become stale on those weekly blogs, so I needed to spread them out all on different days. But they’re all so different, written in different character and tone, that there wasn’t any danger that they would start sounding like each other.

It’s always important to reevaluate what’s working and what’s not. I do this at the end of every week, by comparing my word count and thinking back through the week to see where I could have been more efficient. If we want our writing to become more than just a hobby, it’s a good practice to have.

3. What could I do differently that might result in a larger word count?

I hadn’t really been paying attention to word counts until fairly recently. I usually write everything by hand, so I don’t tend to write all that fast when it comes to rough drafts.

I went back and calculated word counts for the week where my schedule was not as streamlined as it was this week, and the word count was about 7,000 words lower. That’s a pretty significant amount—enough to make me realize that I needed to do something to increase it.

Grouping like writings together had a significant impact on how many words I could turn out in a week, and that was helpful to see. I will continuously experiment to see what might result in the largest word counts (and not just word counts—but also the best kind of writing. Because large word counts doesn’t always mean good word counts.).

As parents with limited writing time, it’s necessary for us to continue streamlining our schedules and figuring out what works best for us in the season we’re in. Seasons change, and our schedules should, too.

Don’t be afraid to experiment. Don’t be afraid to streamline and change things up just because it’s worked for you all this time. You might just find that changing things up significantly increases your production.

But you’ll never know until you evaluate.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Lately I’ve been reading Write. Publish. Repeat. by Sean Platt and Johnny B. Truant, guys who started a podcast called The Self-Publishing Podcast several years ago. These guys are legitimate. They produce a crazy amount of content every year—mostly fiction, but some nonfiction—with word counts in the millions.

In their book, they talk about producing a new episode (they release some of their books like TV episodes—one a week—which is a model I’d like to be trying out soon) every week. Each episode is about 20,000 or 30,000 words.

Each week they’re writing 20,000 to 30,000 words, getting those words into format they can sell, publicizing it, and then launching it to sell.

Let me just say: I can’t even imagine doing that.

Each week I’m lucky to log 25,000 words in rough draft form and another 10,000 or so in final draft form (and that if I’m REALLY lucky and the kids don’t interrupt me even once). I’m lucky to spend a little time compressing something into an actual book I could sell. I’m lucky if I have the slightest amount of time to work on a book description or back matter.

So, of course, lately I’ve been comparing my output to their output and feeling a little discouraged. Will I ever get there? How can I be more efficient? Why can’t I do that, too?

They have a successful indie publishing business, and they produce a crazy amount of product, but what if my not-so-crazy amount of product means that I won’t have a successful indie publishing career?

Platt and Truant talk about the importance of creating funnels, which really means leading one book into another, like with book series or something that will naturally lead readers into another book. They say you shouldn’t launch a book until you have two.

Problem is it takes me six months to write a book. So a year’s worth of work (if I’m lucky) and I can’t even get a book in my store?

Well, here’s the thing, though: comparison isn’t helpful or our own, specific situation.

Sure, these guys are producing an insane amount of content every year, but that doesn’t mean I have to do it exactly like them to run a successful indie business. They’re not even saying that. In fact, they explicitly say in the beginning pages of their book that it’s not a training manual; it’s a this-is-how-I-did-it manual.

They log incredible word counts every week, but that doesn’t mean I have to log the same word count in order to be taken seriously as an author.

Sometimes I catch myself thinking, There’s no way I’ll be able to do that. It’s true for now. But there may be a day I’ll be able to do it, when kids are older and need me less. That day is not today. I don’t have the margin to write for long hours of the day. I will have to take what I can get, because I’m not giving up.

Sometimes we can see these comparisons and think we’re just not trying hard enough or we just don’t have what it takes or we should just quit before we get our hopes up, because obviously we’re lacking something that they have.

Comparison can stop us right in our tracks.

The truth is, writer careers take all different sizes and shapes. Some people can release a 30,000-word book every week. Some people can release a 70,000-word book in a year. It’s all legitimate.

Some writers have kids (lots of them). Other choose not to have kids or family or anything that might distract them from the end goal. It doesn’t mean that either of us is wrong or less or more of a writer.

We can never see ourselves clearly if we’re looking through comparison eyes. We need to take off those lenses that say we should do it that way exactly, like that person, or else…

Or else we’re not going to see success.

Or else they’ll never take us seriously.

Or else our writing won’t be esteemed.

The world wouldn’t be a very interesting place if we all looked the same. The writing world wouldn’t be a very interesting place if all our writing careers looked the same.

So we must do what we can do and let the work rest in our effort for today.

Here are some ways to stop comparison in its tracks instead of letting it stop us:

1. Keep a log of how many words you write each day and celebrate when the word count goes up. Don’t look at others’ word counts. Just look at your own and make yourself better day by day. One word at a time.

2. Start a journal of everything you accomplish each day. At the end of the year, look back on the list and remember. Remember how productive you were. Remember how much you enjoyed it. Remember how exciting it was to build your writer career and how humbling it is that you get to do this.

3. Assess your expectations. Sometimes our expectations, when they’re not aligned with reality, are what can make us look around at other people, because we want either affirmation that we’re on the right path or we want to know if we should set a different goal for ourselves. Make your goals and remember that they’re fluid, not set in stone. And then give it your best effort because you think it’s right, not because someone else’s career told you it was right.

The beauty of building a writing business is that we get to make the rules. We get to work toward our own goals.

Don’t let comparison kill what momentum you already have.

Let me say it again: Don’t let comparison kill what momentum you already have.

(This post is just as much for me as everyone else. I’ll be reading it as often as I need to. I hope you will, too.)

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

In the last month I’ve had some practice calling myself an author.

It’s usually in answer to the question, “What do you do,” asked by people who see my line of boys and think surely I must stay home.

“I’m an author,” I say.

The question that inevitably comes next is “Oh. What do you write?”

And this one is harder to answer, because I don’t have anything out in the market. Yet.

I am still an author. I write books. I finish books. I am in the process of getting those books ready to sell—either through self-publishing (the Speak series and some episodic fiction) or through traditional means (a middle grade novel).

I am an author.

But sometimes I feel like a fraud.

Mostly because there’s so much I need to do, so much more I need to learn, so much experience I need to gain before I can start calling myself a real author, before I can call myself an author and start teaching other people what I’ve learned.

We can feel like before we lay claim to the title “author” or “writer” we have to accomplish this and that, we have to have publishing credits, we have to sell a book well, we have to have a certain number of books under our belt.

But here’s what I’ve come to realize:

A fraud talks about writing. An author does the work of writing.

A fraud keeps all their story ideas in a brainstorm folder for some other day. An author fleshes them out and starts writing the rough draft, even if it takes years to finish.

A fraud is all talk. An author is all work.

So if I’m doing the work of an author, then I have the right to call myself an author.

And I am doing the work. I am writing every single day, cranking out story after story after story in notebooks and on a computer screen and in every space I have in my mama life.

I am an author.

Here are the reasons we should just get over it and call ourselves an author:

1. We know what we’ve been made to do.

Even if those people at the other end of our answer look at us like we’re crazy, even if they ask about our publishing credits (because “author” to others mean we have books on the market) and we don’t have any—yet—even if they don’t believe us, it doesn’t change who we are and who we have been made to be. People have their own standard for what an author should look like. But if we’re doing the work, we deserve the title.

2. We will never feel fully equipped.

It’s taken me a long time to realize this. I will never know as much as I’d like to know. I will never have all the skills I would like to have. I will never be able to produce as much as that other person can produce. There will always be someone better than we are. This is a good thing. It means we have a teacher.

But we can become bogged down in the trenches of this knowledge (or at least I can). We can want to know everything there possibly is to know about writing a book before we do it. There’s nothing wrong with learning what we need to learn. But there is something wrong when it keeps us from creating. The best practice, the best way to become an author or a writer is to practice like one.

3. We don’t have to be the best before we begin.

When I think about people who are masters now—Toni Morrison, Phillip Lopate, Cormac McCarthy, George R. R. Martin—I have to remember that they did not always start here. They did not always start on the bestseller list. They did not always write as well as they do today. Writing well takes practice.

And if we just wait until we’re perfect, until we have our skills in line with where we think they need to be (which will never happen, by the way), we will never seize the opportunity to become an author. We must create now, wherever we are. And then we must constantly grow.

It’s not easy to feel like we’re not putting on some elaborate farce, because who in the world gets to do something as amazing as writing stories for their JOB? Only the luckiest do. Only the best. Only the smartest.

That’s a fallacy. Only the hardest workers do.

So let’s get writing.

Happy creating.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

That’s the question I recently asked of Marcy Lytle, founder of A Bundle of THYME online women’s magazine (well, there were more, of course). In this interview, Marcy shares some wisdom about starting an online magazine, tips and tricks and advice she wishes she’d known before launching.

RT: You are a former math teacher and are now the author of two books and the owner of an online magazine. Tell us about that transition. What made you decide to pursue writing and publishing instead of teaching?

ML: When my kids were small I wrote my own devotions for our family, because I couldn’t really find a book in the stores that kept us all awake! We had hands-on lessons using things we found in the house. Several friends asked if they could receive them too. So after a few years of sending those out, I had enough for a book and contacted a few publishers—and found one interested in publishing. I’ve always loved writing but became a math teacher because I loved numbers too, and there was a need for them in the school system. However, writing is so creative and fun, I’m glad I finally am able to have an outlet for it. After publishing the first book, I took out an ad in a faith magazine, and then they asked me to become the editor. I enjoyed the editing side as well as the creative side—so I was hooked!

RT: When was the first time you thought about starting your own online women’s magazine?

ML: After writing and editing for two magazines for a few years, they both folded, due to expense in publishing for one (it was an actual paper magazine) and expense for salaries in the other (it was online). I began thinking. I have also worked for a magazine subscription agency (family owned) for years, and I receive about a dozen magazines that I love to read. With the relationships I had made on those two magazines, with some other creative writers, I asked if they would be interested in contributing, and they were! One day I woke up with the whole concept of THYME and in about two months’ time we published our first issue online.

RT: What made you want to venture into the online publishing world?

ML: I saw all of the time and expense it took to put together a paper magazine and distribute it. It was all-consuming. I also noticed in my work that many magazines were going totally digital. There was no way I could publish a paper magazine without quitting all I was doing and with some kind of major investment, so digital was a no-brainer way to go.

RT: What kind of work did it take, initially, to get the magazine off the ground?

ML: The hardest part was getting the website up and running and making it user-friendly yet attractive. My daughter had expertise in that area, and she helped me. The first year, I’d say, we were constantly changing, adding, deleting and improving the website itself. So many options and ideas to try out there!

RT: Tell us about A Bundle of T-H-Y-M-E. What’s the significance of its name? Why did you choose women as the main audience? What hole in the online publishing world did you hope it would fill?

ML: Honestly, I prayed and woke up with the herb thyme on my mind and looked up its history. It was actually given to people in bundles to offer them courage way back in history. That seemed like exactly what I wanted to do—offer women courage to have fun, a better marriage, parenting tips, more knowledge of relationship with God, etc. I sat down and came up with the acronym T-H-Y-M-E – tips, home, you, marriage, encouragement—which addressed each category—AND the ladies I had writing all had things to write about in those categories! I chose women because that’s who I had worked with, it’s who I wanted to speak to, and it’s what I knew about – because I’m a woman. I looked at online magazines and saw several faith-based magazines but none quite like ours—with practical ideas and spiritual in the same issue. I wanted to speak to both.

RT: What do you do on a daily basis to keep THYME magazine running smoothly?

ML: I have a whole schedule—from writing, to editing, to creating the pages, finding photos, copying and pasting the articles, aligning, linking, and proofing over and over again. Since we publish monthly, I have those things spread out into four weeks and do a little each week, until the magazine is complete—and oh that’s so fun to see it!

RT: How do you promote the magazine and its articles? What are some of the most effective promotional strategies you’ve used?

ML: I use Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and I’ve taken out a few ads, as well as placed some on Facebook, and have cards made up that I hand out, as well. I’ve promoted it also by sponsoring a Noonday show and other markets where fair trade items are sold. THYME has a booth to help out, and it advertises our magazine. I think the most effective has been on my own personal page and by word of mouth from friends liking, sharing and posting. I don’t really know or have the tools to tell how other promotions have really worked. The hardest part of this whole process is being one person, needing to work another job, and do too much in 24 hours a day!

RT: What have been some of the greatest benefits to running your own magazine?

ML: I love knowing that women are reading and being blessed in their homes, their personal walk with God, their marriages, and trying out new and creative things just for fun. And I absolutely love the writers who write with me and enjoy reading their pieces, as well as writing my own. Writing is very fulfilling, creatively. And it helps when others are blessed.

RT: What have been some of the biggest challenges?

ML: Time and money. It costs to run a website and advertise, and I’d like to pay my writers but I don’t. I don’t bring in very much income at all, and I spend more than I make. I’ve tried several different ways to make money (asking for advertisers to pay monthly, affiliate advertising, and even donations) but I’m not one who pushes people (never liked marketing pushy people) and I don’t want to charge for my magazine, so here I sit publishing it as a ministry, for now…

RT: What do you hope for your magazine’s future?

ML: I’d love to see it grow to have more readers, but I’m trying not to focus on the numbers—that stresses me out. And I’d love to make money to pay my writers. They’re awesome and I’d love to give them something!

RT: What have you learned about online magazines since you started THYME that might be helpful to others who are considering starting an online magazine?

ML: It’s hard work, and if you constantly focus on the accolades or comments from people, it will zap the joy of just writing and sharing . If you know you’re supposed to do it, go for it, and let it grow naturally…and pray a lot…for provision. I prayed for a photographer and we now have one—and when I’ve needed new writers they’ve always surfaced and always had something THYME needed. It’s pretty cool to see that unfold.

RT: What would you do differently if you had the chance?

ML: Not worry so much, and just write.

RT: What advice would you give to those who are interested in running an online magazine?

ML: Try it, and if you find out any cool tips share them with me. If you’re out to make money, count the cost before you begin and get things into place. Make sure that first issue is awesome with no error, so readers will come back a second and a third and a fourth, etc. Stay on top of your schedule, don’t let your issue ever be late, make your readers know they can count on it when you say it’s coming… and finally, enjoy the ride…

(I’d also say to attend webinars or seminars about marketing a website BEFORE you begin. It’s crazy how much there is to know…especially about Facebook – they watch your posts and limit LIKES and all sorts of things, trying to force you to advertise…)

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

But I just don’t have the time.

But I just don’t know what to do.

But I’m just not a writer.

I hear a whole lot of buts from people who don’t think they have what it takes to be a writer—whether it’s the time, the ideas or the talent.

So many writers have grand plans for stories they want to write or projects they’d like to someday start or the career they’d like to pursue instead of the one they’re stuck in right now.

Those excuses can seem like a period at the end of the sentence, but they’re really only parentheticals.

Writer parents are working with an incredible amount of restraint—time and location and ability to think straight for any extended period of time.

In 2013, Forbes Magazine published some data researchers found when conducting a study of “award-winning work from 1.7 million people.” They found that “people who create new value on the job are often inspired by their constraints.”

What this means for us: Constraints can be beneficial.

There is a catch here, though. (Of course there is.)

The catch lies in the way we think about our constraints: not as “barriers to your ability to innovate, but instead as a puzzle that holds the opportunity for creativity and Great Work.”

So everything in our lives becomes a puzzle. The lack of time, the lack of resources, the lack of babysitting. It’s all a puzzle, waiting to be figured out, not a limiting permanent marker line through our dreams.

But I just don’t have the time.

Maybe I can find some.

And then look at all the spaces, where time may be waiting for you to pick up a pen and a notebook and just jot down notes or whole essays or 200 words or 1,500 words.

But I just don’t have the resources.

Maybe I can figure out how to get some.

But I just don’t know what to do.

Maybe I can figure it out if I had a little time to brainstorm.

But I’m just not a writer.

Maybe I could become one.

“Constraints give us a starting point and some building blocks to work with—a problem to solve, an innovative twist to be revealed, or a person to please,” says David Sturt, author of Great Work: How to Make a Difference People Love. “And it doesn’t matter how tightly constrained we feel. The world is filled with amazing possibilities from limited resources and elements.”

Consider colors, he said. Every single variation of color comes from only three: red, yellow and blue. Every song starts with the same twelve notes on the chromatic scale. Everything on the planet is made from only 118 known chemical elements.

Constraints are a “starting point for seemingly endless creativity and possibility,” Sturt said.

So when it comes to writing, start with the constraints. Start with the limited amount of time. Start with the limited ideas. Start with the limited expertise, and then produce your masterpiece. Start a new project. Do the work.

We have lots of excuses for not chasing our dreams. And some of those excuses are really legitimate, because of course the kids need to be fed and put down to bed, and of course they get sick and of course living with children makes life unpredictable and wild, but those constraints can become our greatest catalysts, if we’ll let them.

Constraints are hidden in our buts. We can turn those buts around. We can make them work for us. We can make them help us create the most creative work yet.

Here are some things we can do:

1. Write down your buts. Be honest. Write down everything that’s keeping you from doing what you really want to do—whether it’s starting a blog or launching an online magazine or working on a new project. And then turn your buts into opportunities.

(But I can’t write. But I can learn to.

But someone else is already doing it. But I can add my own unique contribution.

But I’m not prepared for the risk. But I can prepare myself as well as I possibly can.)

2. When a new but comes calling, see it as an opportunity, not as a limit. Constraints can be difficult to work around, but they don’t have to dictate what we do and what we don’t do. We can brave through them.

3. Keep a log of what you have accomplished, especially when the constraints were still in place. This can be valuable. At the end of last year, I felt like I hadn’t really accomplished all that much. And then I realized, after looking back at my work log, that I had accomplished far more than I remembered. Memory can be faulty, so it’s good to have proof.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

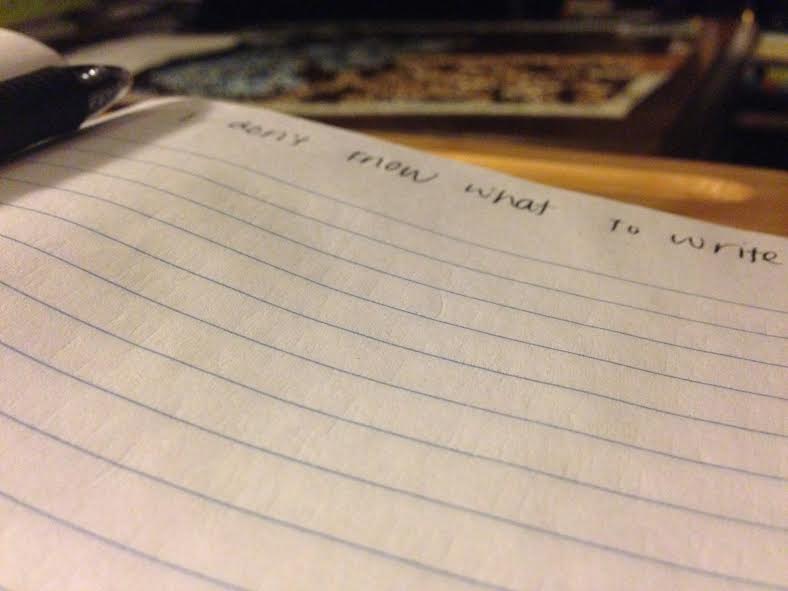

I don’t believe in writer’s block. I do believe that sometimes our mental capacity for our work just dries up.

There are many reasons why our mental capacity to write can dry up. Sometimes we’ve been working too hard on a project, emptying ourselves but not filling back up. Sometimes we’re just too overwhelmed, with other day-job responsibilities or home responsibilities or child responsibilities. Sometimes it’s just not time for a project we’re trying to force.

Whatever the reason, it’s important to remember that writing is painful, if we’re doing it the right way. It’s never easy to open the shades on our inner lives, which is what we’re doing with both fiction and nonfiction if we’re writing it authentically.

We cut and bleed onto the page, and it’s hard work, that cutting and bleeding. If we think it’s easy, we may as well laugh at ourselves right now, because it’s not. We don’t always want to do it. We don’t always love it. We don’t always know why we’re doing it. We just know we have to.

Sometimes I sit down with my notebook open (because I write everything by hand first), and the words come so easily I don’t even really have to try. And other days I sit down and I can find nothing to say, even though I planned the topic a week ago and have given my subconscious ample time to thin it over and contribute to the in-my-head brainstorm that’s always churning.

Writing is not for the weak.

If we have to write because it’s who we are and it’s how we process the world and it’s the way we share our gift with the world, how do we prevent ourselves from getting stuck?

First we have to recognize we’re stuck.

Here’s what stuck looks like:

1. We’re writing in circles, not really saying much.

2. We’re writing shallow, without any depth.

4. We’re writing rough, never writing our way toward a final draft.

3. We’re not writing at all.

And then we have to identify the reasons we’re stuck and address them.

Here are some reasons we might find it hard to fill a blank page:

1. We’re overwhelmed.

Sometimes the demands of our days are just too much. Sometimes we can’t juggle all the kids and the writing and the laundry and the dishes and the dinner cooking and…

It all weighs so much, and sometimes it all looks really ugly, because kids are sick or we didn’t get enough sleep or a deadline is looming. Worry and anxiety are killers of creativity.

What we can do: Ask for help.

I used to think I had to do it all by myself, that I had to earn some badge that made me “Super Mom.” I didn’t need the help. I could handle it. And then I broke my foot. I had to ask for help all the time, for the littlest things.

Life has a funny way of showing us truth.

If we want to pursue a successful career and still care for our children well, we are going to have to ask for help. And we are going to have to take time away from it all—the writing, the children, the home stuff, the day job, everything. We cannot write well if we are walking around with a fever of overwhelm. We have to unload. Go for a walk. Call a babysitter. Lie in bed and stare at the ceiling. Discover meditation. Whatever it takes to feel less overwhelmed.

Our writing needs space. Let’s give it that.

2. We’ve been working too hard.

In her book The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron recommends that artists take an “Artist Date” every week, in addition to a daily walk. Her point in this is that many times we can often get so focused on work that we forget to play.

What we can do: Cancel work and go play.

It’s a worthy act to play. Play frees our mind and allows our subconscious to move in and take over. Especially when we’re stuck, this can mean a story writes itself while we’re playing Candyland with the littles. Get out those board games. Have a dance party in the middle of your living room. Run around the backyard in an epic game of chase. Not only will you feel inspired, but your children will love it, too (especially if you tell them, “I’m working. Let’s go play.”).

3. The internal editors have come to visit.

This is one of the most common reasons writers get stuck in their work. We sit down to write a paragraph or two, and the only thing we hear is, “That’s not good enough. No one will ever read that. You shouldn’t even waste your time.”

Here’s the thing: WE MUST BEAT THESE INTERNAL EDITORS.

We must beat them. They cannot tell us who we are or what we need to do.

What we can do: Write rough drafts every single day.

I’ve learned to beat my internal editors. I get up early every single morning, and for the first half hour of my day, I write. Three pages, college-ruled, black pen, I just write. I write about my worries and I record my complaints and I think of new writing ideas and I write all kinds of random thoughts in this “morning journal.” It’s fragmented and rough, and sometimes my thoughts don’t even really make sense, but that’s okay. All I’m doing is racing the internal editors. Because once they learn they can’t beat you, they’re gone.

So write consistently and often. Write rough. Write about anything in the world. Just keep the pen moving.

4. We’re not present.

One of the most often problems for me is when I’m walking through my life distracted—thinking about that new project I want to work on, working out a plot line in my head, trying to remember what the grocery list had on it. All of this “cerebral living” makes it hard to experience the moment.

And when we’re not experiencing the moment, we’re missing out on some really valuable inspiration all around us.

What we can do: Set a reminder to stay present.

If we have trouble with this one, we can set a timer at different intervals during our day. When the timer goes off, look around and soak in the moment. See the kids playing. Watch the birds outside. Breathe deeply and smell the chicken roasting in the crockpot.

5. It’s just not time for that project.

For years now I’ve been “working” on a fantasy story about a magician named Rindelman. My husband even drew a picture of the magician so I’d have it as a reference. I have the characters all planned out. But every time I sat down to flesh out the plot, I just couldn’t.

New projects would come knocking, and they all felt so easy. I finally realized that Rindelman wasn’t ready to tell his story. This story has been waiting for years, but I know he will eventually tell it. Jus tnot right now.

What we can do: Evaluate the project.

Do we feel passionately enough about it? A book written without passion is just a mediocre project. We can do better than that. Put the idea aside and try again sometime.

I know how hard it is. This is my biggest struggle as a writer, deciding what’s next. I have so many ideas, and I want to do them all yesterday. But timing is so important. If we’re not allowing the book to tell itself in its own timing, we can’t expect a project to be very good.

That old adage “waiting is a virtue?” Well, it’s a virtue for a reason. It means better work when the time finally comes.

6. We might be burned out.

When we’re working too hard, our brain just gets fatigued. We can’t expect it to work endlessly without any rest.

What we can do: Build in some regular rest.

Every seventh week in my writing work, I take a Sabbath rest (in fact, next week is one, and you won’t see any new writing on this page for the whole week). I don’t write any of my normal stuff but allow some space to write some new stuff or not write anything at all. Sometimes I sew or do puzzles. Sometimes I take long naps. Sometimes I spend the whole day with my children.

Rest is so important in the life of a creative. We don’t like to think about it, because we’re writer parents, and it’s important to use every waking moment, especially if we’re working a day job. Isn’t it?

Rest is how I avoid burnout. As writers, our lights are so bright. If we shine them for too long without turning them off, we’re going to burn out.

Feeling stuck in our writing can make it seem impossible to write consistently, but there’s another thing we have to remember:

We are never more stuck than we allow ourselves to be.

This is not a forever-stuck. It’s just a temporary stuck.

Writing will never be easy. Of course it won’t. But with some simple precautions and solutions, we can ensure that it’s richer and better.

That’s a worthy pursuit.