by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

There are many great online blogs that use writers as contributors, but few of them with the reach of The Huffington Post. To get a spot as a blogger for Huff Post is one of the most desirable gigs a writer can get.

In December of last year I decided I wanted to start pitching blogs to some large-traffic sites. The first one I tried was Huff Post.

I had already done a ton of research, because I know it’s required before a writer can effectively pitch to a large publication like Huff Post (in fact, I recommend spending a few weeks getting familiar with the publication’s articles and the style and tone in which they’re written). I combed through the Huff Post Parents site, clicking on the features and trying to get a feel for what might do well on the blog. After a few days, I had an article in mind.

One of the great things about Huff Post is that blog editors accept previously published material, which means that what you post on your own personal blog can be used on Huff Post. My first pitch was an essay I’d written for my parenting blog, Crash Test Parents.

After digging around for a while, I found an e-mail address for the blog editors (blogteam@huffingtonpost.com), rather than the generic contact form (an actual e-mail address is always better). Then I crafted several versions of my pitch. It was my first pitch, and I wanted to get it perfect.

Here’s the one I finally settled on:

Dear Blog Team,

Thank you for taking the time to read my note. As a mother of five (going on six) boys, I hear many jokes from people who know me or don’t: “You know what causes this, right?” “Every time I see you you’re pregnant!” “Do you guys have a TV?” The most hurtful one, I think, is the “Well, my wife and I believe in family planning.”

So I wrote about this misconception in an article called “Just Because I Have a Large Family Doesn’t Mean I Didn’t Family Plan.” I have attached my piece to this message and greatly appreciate the consideration.

There are a few things I would do differently in this pitch today, now that I have so many under my belt. I would probably include a word count (Huff Post blog editors prefer blogs with 800 words or fewer). I would probably add a little information about me. I would change the word “hurtful” to “annoying.”

Five weeks went by and I heard nothing. And then, on the day I’d made a note on my to-do list to try another pitch (because if you fail, keep on trying), I heard from a blog editor, who asked me to join the Huff Post Parents team.

My first article printed at the end of January (almost two months after I pitched it), and was a feature right out of the gate. It resulted in more than 200 comments and more than 1,200 Facebook shares, 25 tweets and 17,000 likes.

I’ve been blogging for them ever since.

Huff Post doesn’t pay you for your blogs, but reusing your blogs can make that time worthwhile. They allow links to your original material, which can draw people onto your own platform (always the goal).

Traffic to my web site increased dramatically once I joined the Huff Post Parents team, because people who liked my article wanted to see what else I’d written.

Once you become a blogger for Huff Post, you get a blogger profile and can submit blogs as often as you want. I try to submit them at least once a week, although the publishing schedule varies, and I don’t always have one article posting every week. Sometimes blog editors are inundated with submissions and a blog can sit in a queue for six weeks or more.

One of the biggest drawbacks, for me, is that many of the people who comment aren’t always the nicest people. I tend to have a pretty thin skin, so sometimes it gets to me. But if you can step away and answer their unkindness with kindness, you win others to your platform.

Overall, Huff Post Parents and its other affiliates (I’ve since been published on Huff Post Education and plan to pitch a few to Huff Post Religion) is a good move for visibility and introducing others to your platform.

Important tips:

1. Make sure you have an engaging headline. If blog editors don’t know who you are, the first thing they’ll see in your pitch is the blog title. Make them want to read it.

2. Clean your copy. Make sure your copy is free of errors. It just makes working with you much easier for these editors who deal with thousands of queries and blogs every day.

3. Try and try again. If more than six weeks goes by, try another pitch. Keep trying until you get something accepted. But don’t keep trying without looking at what might be unappealing about your pitches–whether it’s the article or your e-mail. Analyze and learn from every rejection.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

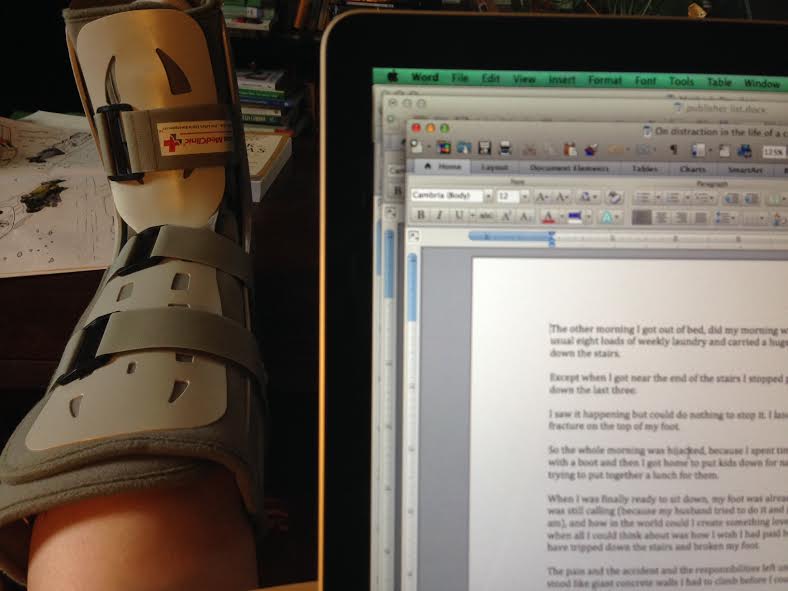

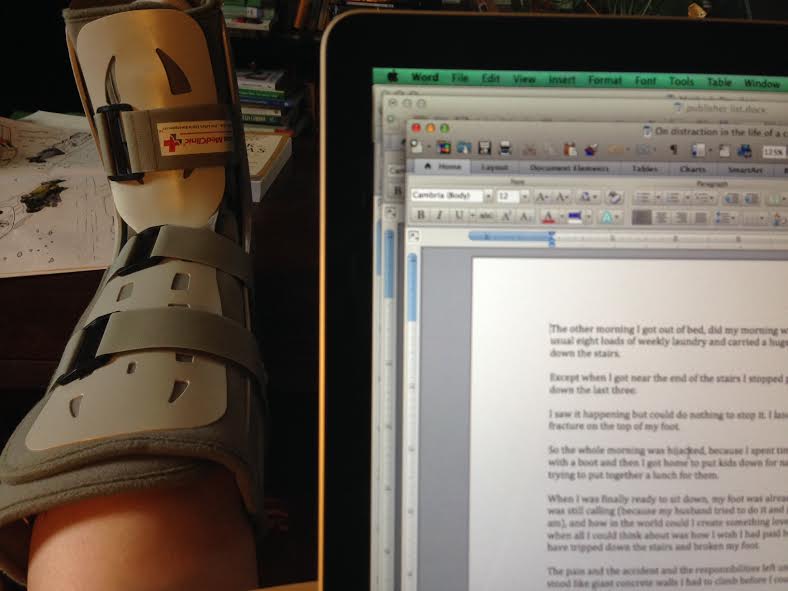

The other morning I got out of bed, did my morning writing, worked out, sorted the usual eight loads of weekly laundry and carried a huge hamper full of dark clothes down the stairs.

Except when I got near the end of the stairs I stopped paying attention and tripped down the last three.

I saw it happening but could do nothing to stop it. I landed so hard I got a hairline fracture on the top of my foot.

So the whole morning was hijacked, because I spent time with a doctor and time with a boot and then I got home to put kids down for naps after hobbling around trying to put together a lunch for them.

When I was finally ready to sit down, my foot was already throbbing, and laundry was still calling (because my husband tried to do it and just isn’t as good at it as I am), and how in the world could I create something lovely and eloquent and useful when all I could think about was how I wish I had paid better attention so I wouldn’t have tripped down the stairs and broken my foot.

The pain and the accident and the responsibilities left undone because of them stood like giant concrete walls I had to climb before I could focus on creating anything of value.

Sometimes artists have days like this.

Sometimes the kids get sick, and we worry about them and they just want to be near us and creativity flies right out the window every time they cough in their sleep or try their hardest to make it to the bathroom and inevitably fail so it’s all over the carpet instead.

Sometimes the doorbell will ring when we’re right in the middle of flow, right in the middle of writing a word, because the lawn team mowing our neighbor’s yard noticed you might need help with ours.

Sometimes we will trip on our way down the stairs or smash our finger in the car door or cut our hand trying to slice an apple.

Distractions will come in the life of artists—because we are living life (and if we aren’t, our art suffers anyway).

We can’t avoid the distractions, so we must learn to overcome them.

The thing is, we can be made better artists on the hard-to-create days.

If we create anyway.

Because do you know what distraction learns in our creating anyway? It learns that it has no real power over what we decide to do, no real power over us.

What distraction wants is for us to give in. Stop creating. Put it off until tomorrow, or the next day or the one after tha tone.

We can’t. We won’t.

We will create anyway.

Even if we can feel our heartbeat in our foot, we will create. Even if the doorbell rings, we will create. Even if the baby didn’t sleep last night, we will create.

What we create in the face of distraction may not be our best work or even close to it, but it is still practice. It is still valuable.

Distraction still doesn’t win the day.

So that day, even though my foot throbbed and my brain felt foggy and my words didn’t want to come out from hiding, I wrote.

I threw everything out, started over from the beginning all the days after, but I still made something out of nothing.

Distraction did not win.

Challenge: Think of your most common distraction. Write a letter to it. Be serious or funny, but most of all be honest. Tell it you will create anyway—and then do it.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Every morning at 4:30 I crawl out of bed and reach for my glasses (usually knocking a book or two off my bedside table) and trip to my blue wing chair, where I turn on the lamp and open my morning notebook.

And then I write three pages—about 900 words—on whatever comes to mind.

I have no agenda. No purpose. I just write.

It’s an idea I got from Julia Cameron, a creativity teachers and author of The Artist’s Way. Cameron calls these writing sessions “morning pages.”

When I first read about them in one of her books, I was skeptical. She advocates that you get out of bed half an hour earlier than normal, and, good grief, I already got out of bed at 5. I wondered how I might possibly benefit from less sleep and more writing, when I already wrote nonstop between the hours of 12:30 and 5:30 p.m. Wasn’t that enough?

Still, I decided to give it a chance.

I’m hardly ever completely awake when I’m doing my morning pages, but I have never had to search for anything to say—mostly because the point of morning pages isn’t really to say something profound or true or worth using later (although sometimes that will happen naturally).

The point is to clear a cluttered mind.

I think of them as my writing meditation.

In my morning pages, I unload all the stress that weighs on my subconscious—that payment a client has yet to make, my little boy’s complaint about his tummy hurting last night, how I really don’t want to take on that assignment but feel a little pressured to.

Every now and then a new story idea or an essay topic will find its way into my pages, but that’s never the goal.

The goal, at its simplest, is to clear a mind of it unnecessary weight so we will have more room to create and move and make beauty for the world.

When we are so weighed down by worries and concerns and things to do, we cannot freely create our art.

So writing first thing in the morning, to break free of those weights, is not just for writers. It’s for all artists.

Creativity begins with writing.

When we write, whether it is a record of our day or a 100,000-word story we’re trying to sell, our world becomes clear. We find ourselves in words, in all the poetry that finds its way into choppy sentences or long, flowery ones that say something or nothing at all.

Writing opens up space in our minds so we can envision more and dream bigger and create in a new dynamic.

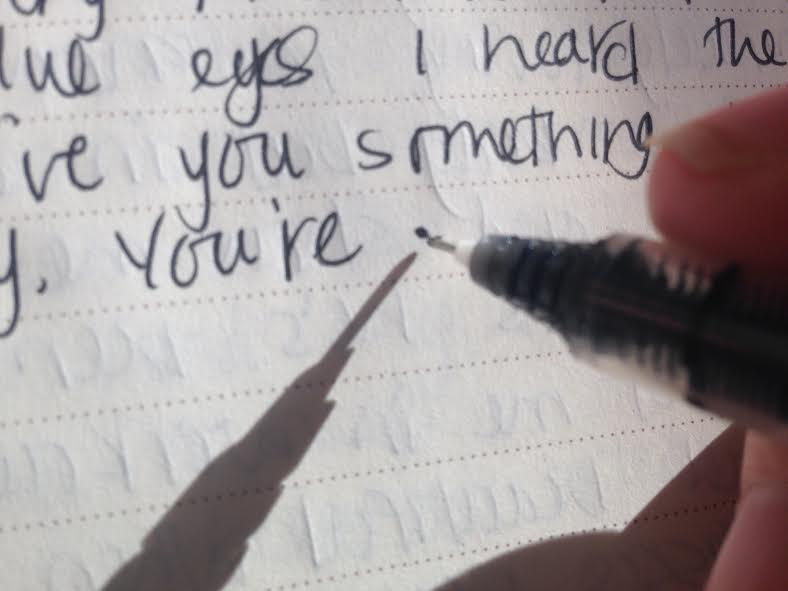

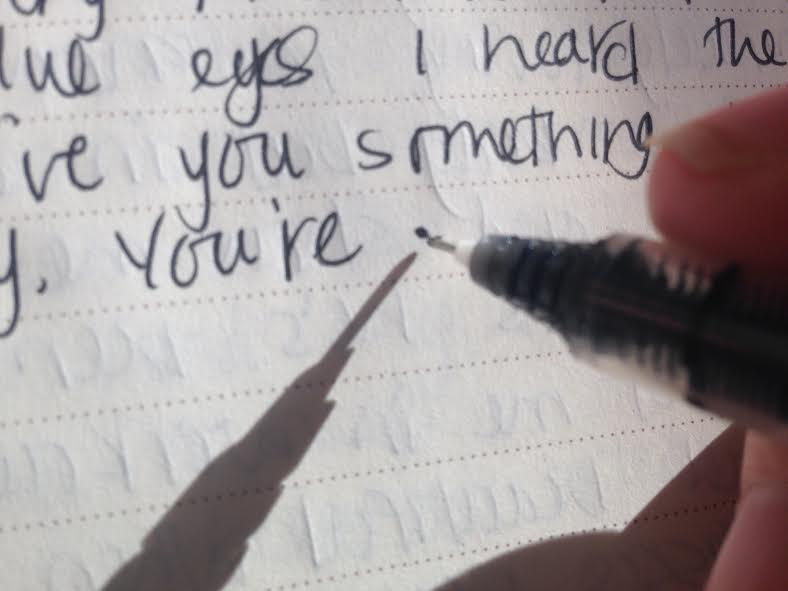

It’s up to us how that writing is done. I do it in a composition notebook, by hand—mostly because studies show that the motion of our hands gets our brain thinking more creatively.

But also because when we write by hand, we have a record of our days. We can see our handwriting and how it changed from day to day and mood to mood—how in those days’ records right there, the baby I was holding kept kicking my hand in the middle of a word. And right there is when I felt so passionate about what I was writing that the passion showed itself in hurried handwriting and water splotches. And right there—that’s where I couldn’t write fast enough for the speed at which my brain was working, so all the letters run together in excitement.

My morning pages tell a story of exhaustion and worry and excitement and gratitude and joy and motherhood and creativity and hope.

It is the place where I have written, “I’m tired of doing things for free,” and those words helped me realize I was giving too much of my writing away and not asking enough compensation for my value. It is the place where I have worked out how I would most like to use my gift. It is the place where I have renounced the fear that I will do all this work only to see nothing come of it.

I don’t look back through those early morning pages often, but I plan to. Because there are jewels hidden in my stream-of-conscious writing, and I want to find them.

Writing can make a world clearer. It can tell us more about our true selves. It can help us work out the places where we feel stuck and trapped and too heavy to fly.

All of this informs our creativity.

So get out a notebook and write.

Challenge: Try morning pages for the next month. Set your alarm clock half an hour early (I know, I know how hard it is!) and write without stopping until you have filled three pages. Don’t worry if it sounds petty or trite, or if it doesn’t even make sense because you’re half asleep. It’s better that the petty and trite get down on paper instead of clogging your creativity.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

(Photo by Steven Salazar)

(Photo by Steven Salazar)

A couple of weeks ago my husband and I had the privilege of attending a creative conference called Creative South.

All week leading up to the conference I felt anxious and a little overwhelmed, because there was still so much writing work to do, and I could not see how I could possibly get it all done when we were traveling one whole day, so that was a day lost, and we would be meeting people from our creative community another day, and that would be a whole other day lost, and we were going to be tied up in sessions for two whole days after that.

I’d look at my to-do list and everything that needed finishing, and I would get a sinking feeling in my stomach.

And then we spent 18 hours in the car brainstorming topics for the podcast my husband and I will be launching May 7. We brainstormed courses we want to develop about real-life parenting. We brainstormed a marriage book I plan to start writing later this year.

We spent several hours in Georgia coffee shops meeting face-to-face with people in our online community and digging right in to deep, challenging conversations and making new friends.

We spent days in sessions on creative strategies and building platforms.

My to-do list sat neglected, but do you know what?

I came away with so many new ideas for topics and projects and wisdom about how to do things that I finally just had to cut those ideas off (not really. I never cut ideas off. I have a brainstorm binder that’s just a lot thicker now.).

What I’ve found is true in my life is that sometimes we have to step away from our idea of the way things should go so we can embrace a better way we didn’t even know we needed.

There is a point in every creative life when we have been working for so long and in the same environment with the same amount of time and the same people and the same challenges that we become, maybe just a little bit, stale.

Sometimes it takes getting out of the normal routine to find new life in our old creations.

Routine is helpful in the life of a creative. It gives us specific, consistent time in which to create. Every day. Without exception.

But throwing out the routine, every once in a while, is also helpful in the life of a creative. It invigorates our creativity so we can push through to the finish or just remember why we started doing it in the first place.

Julia Cameron, one of the best teachers on creativity, calls these getting-off-routine blocks of time “Artist Dates.” She recommends that artists take one a week.

It doesn’t always have to look like a weekend conference. It can look like a 30-minute break where we get outside our house and see other human faces, besides the ones we see every day, and hear other voices and observe new beauty.

Being a creative can be a lonely life. As a writer, I hole myself away for hours at a time, just working on my craft. Sometimes, if my kids don’t barge in right after school to say hello, I can spend that whole five hour without any human contact whatsoever.

It’s good for me to get out once in a while. It’s good for me to sit beside my husband for an uninterrupted road trip and brainstorm what we’re passionate about. It’s good for me to meet new people and hear new stories and share in new experiences.

The out-of-the-ordinary informs our art just as much as our ordinary.

At the end of our trip, my husband and I had 77 podcast episodes, the beginnings of a new sci-fi novel, a dozen article topics and more. I edited a book, wrote on another novel and wrote fifteen poems.

My to-do list wouldn’t even know what to do with productivity like that.

Sometimes a to-do list can be filled with all the exact right things when we take time away from it.

After all, the unexpected can hold some of our greatest inspiration.

Challenge: Try an Artist Date this week. Take a walk. Visit a bookstore. Have coffee with a friend. Don’t think of it as work time you’re giving up but as time you’re using to inform your work. Our mental shifts can set us up for new perspectives, which, in my experience, is always a win.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

This week my husband and I spent three days at a creative conference.

Mostly it was designers and illustrators, no writers at all, but still it was amazing to be in a place with so many other creative people and admire their work from the sidelines.

And then.

On the last day, a friend of mine spoke about building a platform from a business perspective. It was helpful even for me, even though I come from a completely different creative pursuit, and I knew it would be especially helpful to all the other hand-lettering artists who are trying to do what he has already successfully done: get their art recognized and appreciated.

Right after his talk, someone tweeted something disrespectful and rude and, frankly, immature.

Someone who was there.

Someone who was one of us.

And, see, I just felt so angry. I felt angry for my friend and for hand-lettering artists and for all of us.

And then I felt sad.

I felt sad that we can feel so threatened by someone else’s success that we think it says something about us. That we feel the need to discount another artist. That we let hate slide in to our hearts.

I felt sad that we don’t know how to share our space well.

I felt sad that we seem to have so much trouble finding a way to cheer one another on in our similar pursuits.

I am no exception. I have never ridiculed publicly, but I have felt threatened and ruffled and discounted and territorial and afraid.

This needs to change.

Our inability to share the art world and support other artists and help these talented people do what they do really just boils down to fear.

We are afraid that if a writer is successful with their writing, there will not be room for us. We are afraid that if this artist “makes it” with that hand-lettering style that looks so much like ours, there will not be any work for us. We are afraid of that husband/wife musical duo gaining 1 million followers on their YouTube channel because we think it means we will never see an audience gather around us.

Saturation of the market is a lie.

Saturation of the market says we live under the laws of scarcity.

It says:

1. There is not enough to go around, so we must be the best.

2. If someone else is more “successful” in their art than we are, we must not be the best.

3. We must protect ourselves by proving those others artists are not the best.

Best and better and all those other comparison words have no place in the creative world, unless we’re talking of our own progression of art. When we are comparing our work to another’s, we are an island of alone, and artists cannot survive and keep creating art on an island of alone.

Because, at the heart of it all, we are people. People need relationships. People need community.

Comparing kills relationships. Championing restores them.

So there are some things I want us to remember.

1. There is enough room for all of us.

2. The way our art expresses itself through us is not the same way art expresses itself through that other person (unless we’re intentionally trying to copy them).

3. We belong to each other.

The last one is the most important.

We are an artist community. Creating beauty for a world that may or may not appreciate it is an incredibly lonely pursuit, and we need to be cheering each other along the way.

We need to admire each other and we need to be admired, but we will do neither if we’re only interested in discounting those by whom we feel threatened.

We need to be giving to each other, not taking away.

Giving instruction. Giving away our secrets. Giving away the strategies that have worked for us. Giving support. Giving encouragement. Giving lessons we’ve learned so others don’t waste their time making the same mistake that cost us a year.

It feels scary to give when this is our livelihood, but relationships are ALWAYS better than existing alone.

So let’s take care with each other’s hearts. Let’s respect one another for who we are.

Let’s turn our lonely art into community art.

Challenge: Introduce your followers to another artist whose works you admire or to someone by whom you feel threatened. Oftentimes feeling threatened by another’s work only means we are operating under the lies of scarcity. Root out those lies and share another’s art. Encourage them. Champion them.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

It took me way too long to call myself by what I am: Writer.

Because I worked another job, and I had a title there—journalist—and what I did in the margins—writing—wasn’t really who I was.

Or at least that’s the lie I believed for years.

I tried to do without writing, for a time, because there were babies, one after another, and the margins felt cramped and tight, but the need to write always blazed from within.

Creating something from nothing, arranging and rearranging words into art felt good and right and true, but when people asked me what I did, I gave them my job description—“I produce a newspaper.”

Because producing a newspaper seemed like a more viable job than “writer.”

And then I lost my job.

I stumbled along for a while, worried that I would not have anything to say to people when they asked, “What do you do?” because I had no “real” job.

I had the writing I did in the hours I could manage it, but I knew that wouldn’t satisfy them. I was not published, at least not beyond magazines and newspapers. I was not legitimate.

I didn’t create rain or shine, eight hours every day, because there were always babies crying and dinner to prepare for perpetually-hungry children and fun days to plan on the weekends, when we were all finally together without work pressing in on us.

And yet I still wrote consistently. Every day. Some days it would look like opening a journal and jotting 200 words down before a kid started screaming, but I was still doing the work. I was still showing up.

I was a writer.

I wrestled with that question, “What do you do,” for a couple of months before I finally found myself able to answer, simply, “I write. I am a writer.”

We can feel like phonies tossing those words around. Writer. Dancer. Singer. Painter. Sculptor. Artist.

Because doesn’t everybody do it now?

Aren’t all the arts incredibly accessible to all people now?

Of course they are, but that does not make me any less of one.

I am a writer because I do the work. We are artists because we do the work. So we should start calling ourselves by our true names.

It can feel uncomfortable, because we don’t think we’re legitimate, maybe, or because we don’t have a publishing contract or ten million followers or unlimited hours to pursue our craft.

But the truth is, all we have to do is show up. Every day. For ten minutes or ten hours.

Maybe it takes us a few months to settle into that name, but when we are brave enough to try it on for size, we will see that it really does fit.

We will see that we become what we speak over ourselves. When we call ourselves an artist, we will become an artist.

There is something about calling out our true nature that helps us live into it.

So we must let go of the fear. We must dismiss the fear of what “they” might think. We must dismiss the fear of what it might mean, the commitment it might demand (and it will commitment. But if we love it, commitment will come naturally). We must dismiss the fear that we are not good enough to call ourselves by our true names.

We are good enough.

Becoming an artist is more about what we do than anything else.

Do we create on a daily basis?

Yes.

We are artists.

Do we show up for the work even when we don’t feel like it?

Yes.

We are artists.

Do we burn to pursue the art that lives inside us?

Yes.

We are artists.

It really is simple. But we must first climb over that mental mountain that says we may not be who we say we are. And this takes everyday work, every day pulling out a notebook and writing, pulling out an art book and sketching, pulling out a guitar and tinkering with that new song.

Artists become artists in the practice.

So let’s get practicing.

Challenge: Wear your artist hat for a week. When someone new asks you what you do, tell them you’re a writer or a painter or an actor or whatever you are, at your deepest place. Sometimes saying it aloud to someone else helps us believe it more easily.