by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

Since you’re having such a wonderfully imaginative September, I wanted to send a short-ish note about collecting ideas.

Collecting ideas, for me, is incredibly important. I don’t ever want my ideas to slip through my unprepared fingers.

But we’ve all been there: Washing the dishes when a brilliant idea crashes into our brain regarding how to motivate our kids to pick up after themselves. In the shower when we solve the problem in our story that’s been stumping us for the last week. Awake in bed, in a dark room, our partner sleeping beside us while we might have solved the world’s climate crisis (I wish that would happen for me. Truly.).

I am of the opinion that every idea deserves to be captured, no judgment. I write down every idea that comes to me, regardless of whether it ever progresses beyond just an idea.

There are, today, many different ways to capture ideas. And, again, I’m going to be super helpful and say: It depends on what works best for you. But here are some ideas.

1. Paper and pen

This is my preferred method of capturing ideas, whether it’s brand-new story ideas, ideas for the stories I already have in process, things relating to family and the home, relationships, etc. I have multiple file folders labeled “story ideas,” “meal plans,” “family issues,” “poetry ideas,” “summer” (yes, it needed its own folder). I also keep multiple journals with quotes that spark ideas. These ideas, which are rarely developed beyond a line or two, go on pieces of printer paper, with plenty of room for elaboration. I also carry index cards and a pen bag around with me everywhere I go. And a stack of notecards in the drawer of my bedside table. Preparation wins.

2. Phone, computer or other tech

You can do all of the above with your phone or computer or iPad or whatever tech you desire. There is absolutely nothing wrong with capturing ideas this way, and in some ways it might be better (you’re not using paper, and you don’t have to flip through a ton of papers and sort through folders when you’re trying to find something specific). I just don’t happen to gravitate toward technology naturally; when an idea strikes from nowhere, I reach for a pen, not my phone. My husband is the complete opposite. And he uses the voice recording feature on his phone to record melodies for songs, even if there are no lyrics—which you can’t do on paper. I mean, I guess you could, but it would be much more time-consuming.

3. A mix of both

Maybe, in certain instances, one might work better than the other. This is why I say it’s an experimental process and that we each have to find what works best for us.

But in order for it to become an experimental process, it first has to become a habit. Build the habit, put the process in place, and you’ll start collecting more ideas than you know what to do with.

There’s a mysterious, magnetizing effect ideas have when you start collecting them. It almost makes a person wonder if the ideas appreciate your acknowledgment and thus attract more.

I hope we all say, “My mind is wide open! Bring on the ideas!”

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

When I visit kids at schools, someone usually asks me if I just write my book and that’s that. It’s a humorous question to me; a book is hardly ever finished the first time it comes out on paper (there is, of course, the very, very rare exception). But students are often surprised to know just how many drafts my books require.

It’s impossible to say, when I’m first starting a book, how many drafts it will take to perfect it (in my eyes, at least). Drafting is like starting with a big block of wood that has little shape and whittling it down to something artistic and beautiful. Sometimes that can be done in five drafts, sometimes it takes twenty. Most of my books take seven or more—intentionally. I have a process that infuses time and space into the workflow, and that is necessary, for me, to write the best book I can. Time and space allow me to approach my manuscripts with the impassivity of a reader reading it for the first time.

The above picture is my workflow. I spend the bulk of my time researching and brainstorming characters, plots, locations, emotional arcs, and character relationships. Once that’s finished (and sometimes I have 20,000 words of brainstorm during this stage), I write the first draft. I don’t self-edit, don’t change anything, try not to even backspace for this first draft. I just get all the words onto the page as fast as I can. Then I set the manuscript aside for a month or two.

Draft two is for deepening scenes, focusing on the emotions and descriptions, bringing settings to life. Once finished with draft two, I again set the manuscript aside for one or two months. Before draft three I read through the manuscript and make notes—what are the confusing places? Are there any plot holes? What needs more research to really come alive? Are there inconsistencies? I make a triage list of what needs tweaking in the next draft.

Other drafts focus specifically on language. One draft includes multiple “passes,” reading through the manuscript for specific things—one pass for characterization, one for dialogue, one for beginnings and endings of chapters, one for symbols, motifs, and epanelepsis (returning to something later that was introduced earlier but changed).

My process differs between picture books, poems, and essays, but at the heart of it, it remains the same. Books and poems and any piece of writing takes time, and we can’t rush the process. I find that every draft I do—some of them complete rewrites, some of them just tweaks—brings me closer to the heart of my story.

How do you know you’re done? I don’t have a definitive answer for that. Every story is different, and the truth is, you likely could go on revising forever and ever. I could revise my published books, if my publisher permitted me. At some point, in order to get our work out into the world, we have to type, “The End.” You’ll know when it’s the right time.

Don’t be afraid to let it go.

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

I’m a very task-oriented person. I make my goals, I make my list of tasks to support those goals, I work myself every hour I have and don’t quit until the clock says my work day is officially done.

This means that while I accomplish a ridiculous amount of tasks during my working hours, I also creep close to burnout frequently.

I solve this problem with rest.

Every six or seven weeks (depending on my sons’ school schedules—I like to match up my time off with their holidays from school) I take an entire week off work. I don’t do anything work-related. I read some books, hang out with my kids, play some board games, maybe even do a little sewing. I play. I take naps. I breathe.

I call these weeks Sabbaticals. They are my time to recover from my weeks of focused and intentional work.

I’m coming up on the last Sabbatical of the year, which extends for two weeks, as a sort of celebration and goodbye to the previous year and welcoming of the new year (plus, my kids are out of school for two weeks and counting down to Christmas Day, and getting any work done is highly unlikely). I use this two-week break to make New Year goals, prepare for the holidays, and schedule my next year—including Sabbath weeks.

When you spend so many weeks (even if you don’t have many hours in a day) in such focused and intense work, burnout is a given. Add to that family life and adult responsibilities and the unpredictability of life, and it’s a wonder any of us get anything done.

Intentional rest opens up the space to breathe again—which is necessary to create.

Resting keeps me focused on and energized for the work ahead of me—and I’m always ready to get back to work once those seven days (and especially the fourteen days) have passed.

(Note 1: I don’t completely forbid myself to write during my Sabbaticals; writing often keeps me sane when I’m home with my sons. And creative work is never really predictable. If the urge strikes me to write something—as long as it’s not a project I’m currently working on—I write. It’s usually something playful or silly or experimental that could potentially become something greater someday. I never want to lose that opportunity to create something new, but I do want to rest well.)

(Note 2: Your Sabbatical will look different than mine. There is no one right way to do it.)

(Photo by Angelina Kichukova on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life, Wing Chair Musings

One of the most difficult and yet important pieces of the writer life is believing in yourself and believing in your work.

I have a book that just launched into the world (two days ago, to be exact). This is my first traditionally published book (but certainly not my last). I am currently in the launch season, and I’m feeling all the feelings that a writer can possibly feel. Nervous, ecstatic, terrified.

Yes, mostly terrified.

Is it really a good book? Will others think so? Am I good enough?

That’s what it really comes down to: Am I good enough?

Earlier in this pre-launch season, I was having dreams that various people at my publishing house would come to me and say, “Oh, never mind. We’re not publishing this book.” Dreams where no one bought the book and online reviews were filled with hate and criticism. Dreams where my book vanished in a cloud of gray smoke, just another unremarkable book in a world of them.

My husband is a very perceptive man. He has noticed my distraction, and, though he has been baffled by it, he has also been angered (in a good way) about it. The other day he stood in front of me, wrapped his hands around my upper arms, and said, “Do you believe you deserve this?”

Do I believe I deserve this? I wasn’t really sure how to answer the question.

Do I?

In some ways, yes. I work hard both to improve my craft and to produce the best stories I can possibly produce at any point in time. I put in the work—I get up at 4:15 in the morning so I can squeeze in some writing before my kids start begging for breakfast. I write in the afternoons, when I could be hanging out with my kids. I write in the evenings, sometimes, when I could be sleeping.

I write daily. I practice all the time. I focus on what needs doing, and I do it. I always have.

But in most ways, or at least the ways that matter, no. I don’t believe I deserve this.

I grew up in a home where my mother supported everything I did—to the point of keeping, still, now, a box underneath her bed with all my writing compositions from grade school on into college. But there was a missing dad. And when there’s a missing anything, we grow up with a large hole inside us, a hole that whispers:

You’re not good enough. You never will be.

You don’t deserve this. You never will.

It’s only a matter of time before they find out you’re nothing more than an abandoned girl.

This persistent whisper can derail a writer. Because the mental game is most of the game.

I have fought hard for this dream. I started from the ground up; I had no connections, no credits, nothing to recommend me to the world except a story and a drive to work hard and a conviction to be better tomorrow than I am today.

But maybe—well, maybe that was enough. Maybe it still is enough.

Do I deserve this? Yes. I do.

Do you deserve this? Yes. You do.

Believe that your hard work and persistent practice will pay off. Believe that you can reach your dream. Believe that your dream is glad you have found it, embraced it, fought for it.

Mostly, believe that you deserve it.

by Rachel Toalson | Books, This Writer Life

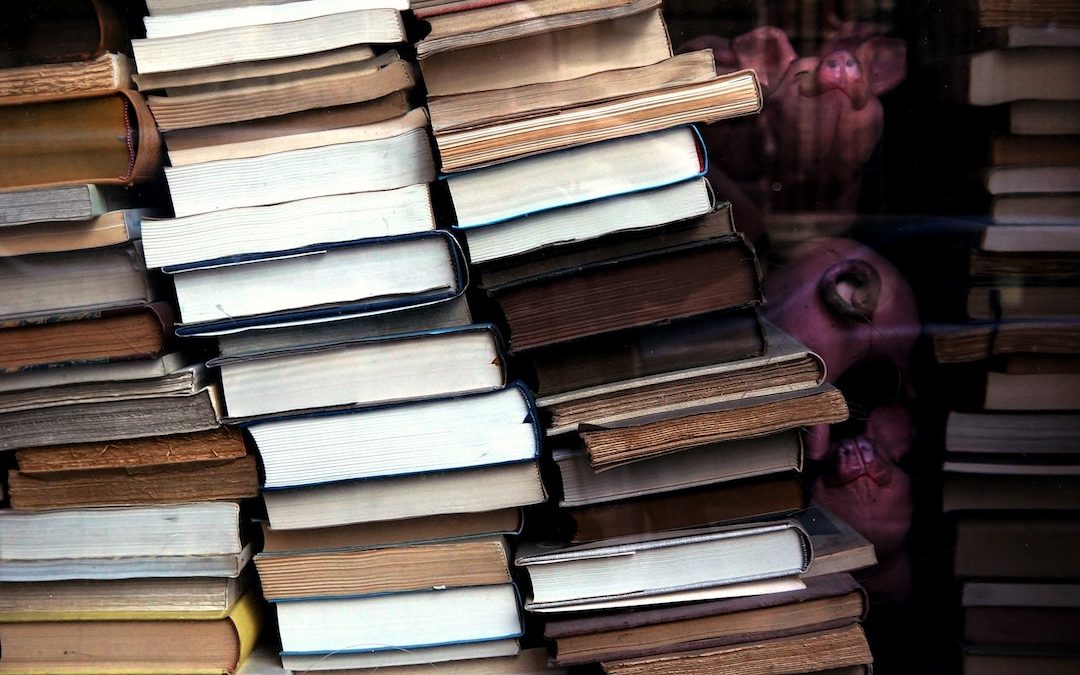

I once heard a writer say that she could usually finish all the research she needed to do for a story in about a week.

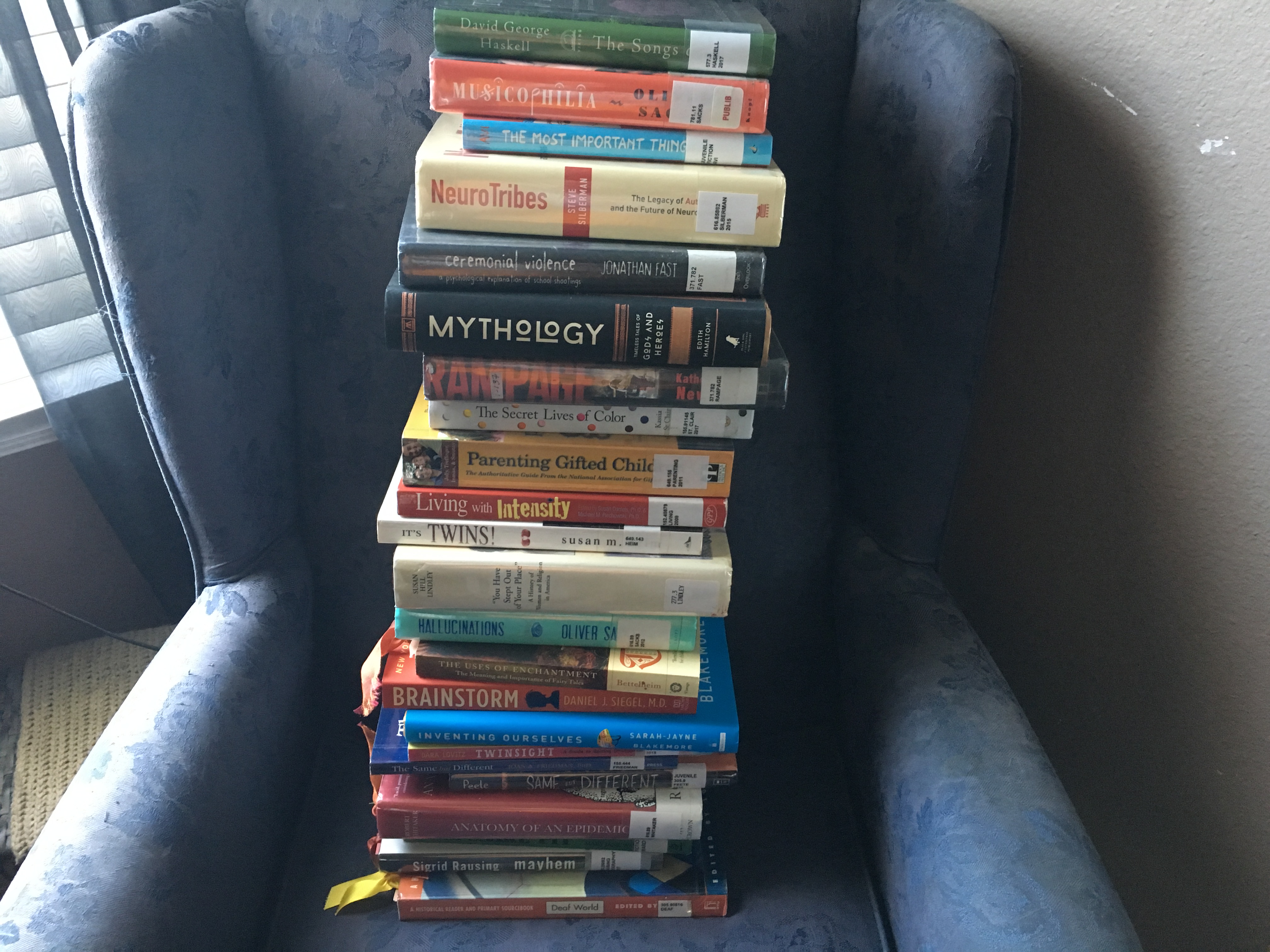

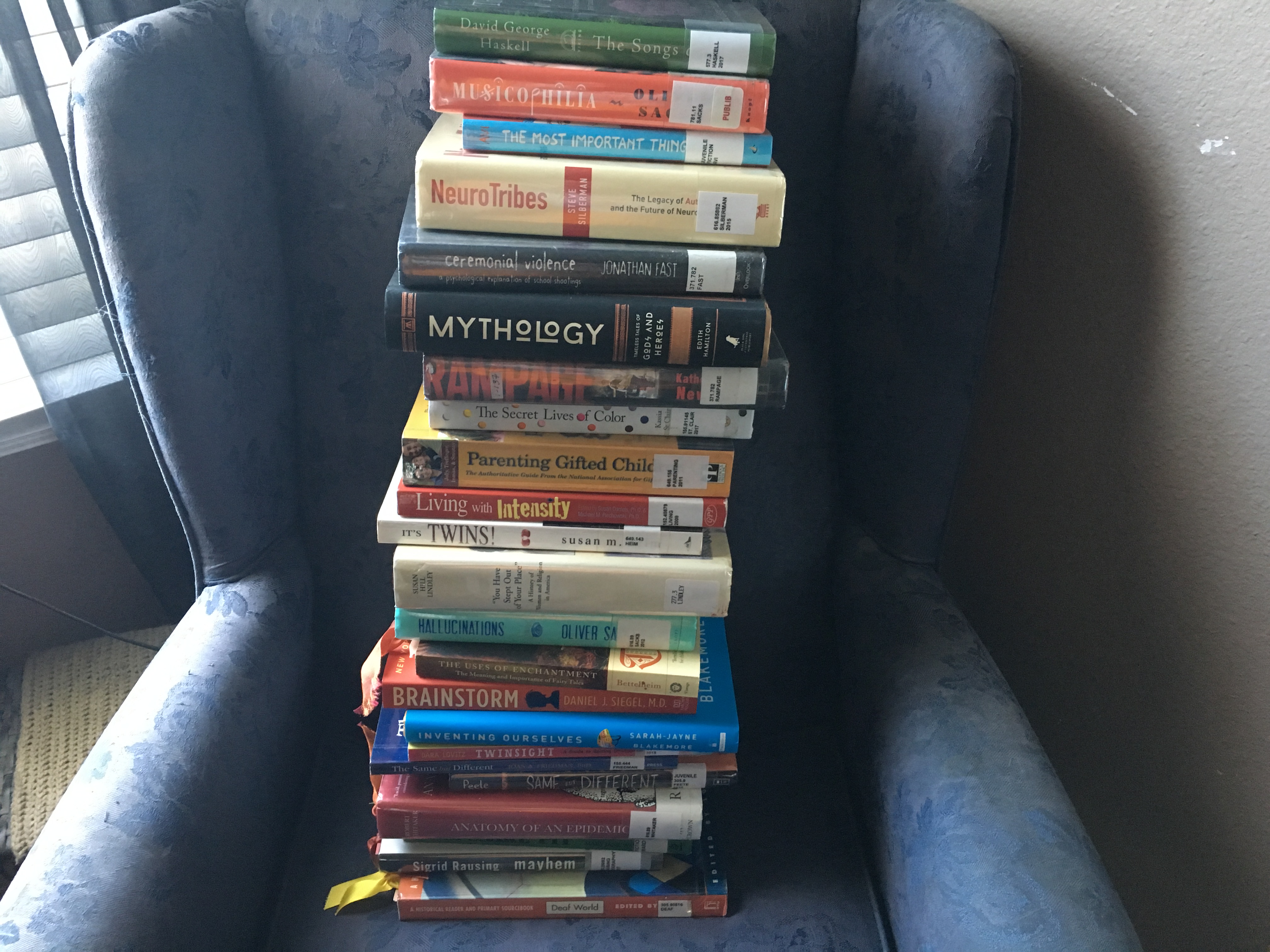

Meanwhile, this was my research stack for the summer.

It could be because I’m a former journalist, but one of the biggest challenges for me is knowing when to quit research.

It might seem strange to think about a fiction book needing so much research, but part of our responsibility (or so I believe) as writers is making sure that whatever we’re trying to portray—whether it’s a character who’s a twin (and don’t ever assume that just because you’re the parent of twins, like I am, that you completely understand the neurological and psychological characteristics of twins; I’ve learned so much from my research, which has, fortunately, also informed my parenting), or a place that’s becoming swallowed up by gentrification or a character who’s obsessed with trees—is portrayed accurately within the scope of our story.

The first thing I do during my research stage is put a bunch of books on hold at my local library. Usually all the holds come up at once and then I have to decide which books I’ll read first. Some of the books are more helpful than others for what I’m specifically trying to do, but I like to read as many of them as I can; I don’t think you can ever do too much research (unless, of course, it’s your excuse to avoid writing).

My second wave of research is interviewing people who have lived the lives I’m trying to portray. For example, I currently have on submission a young adult novel about suicide and depression. Even though I’ve experienced both of these things in my life (I was never suicidal, but someone very close to me was), I wanted to reach out and talk to more suicide survivors and their parents to record their experiences. Even if I don’t use any of what I’ve collected from these brave, resilient, remarkable teenagers, the more information I have, the more it helps me better portray whatever issue I’ve chosen in a story.

Which is much better than relying on stereotypes.

So take your time researching. You never know what you’ll find or just how much it will improve your story.

(Photo by All Bong on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | This Writer Life

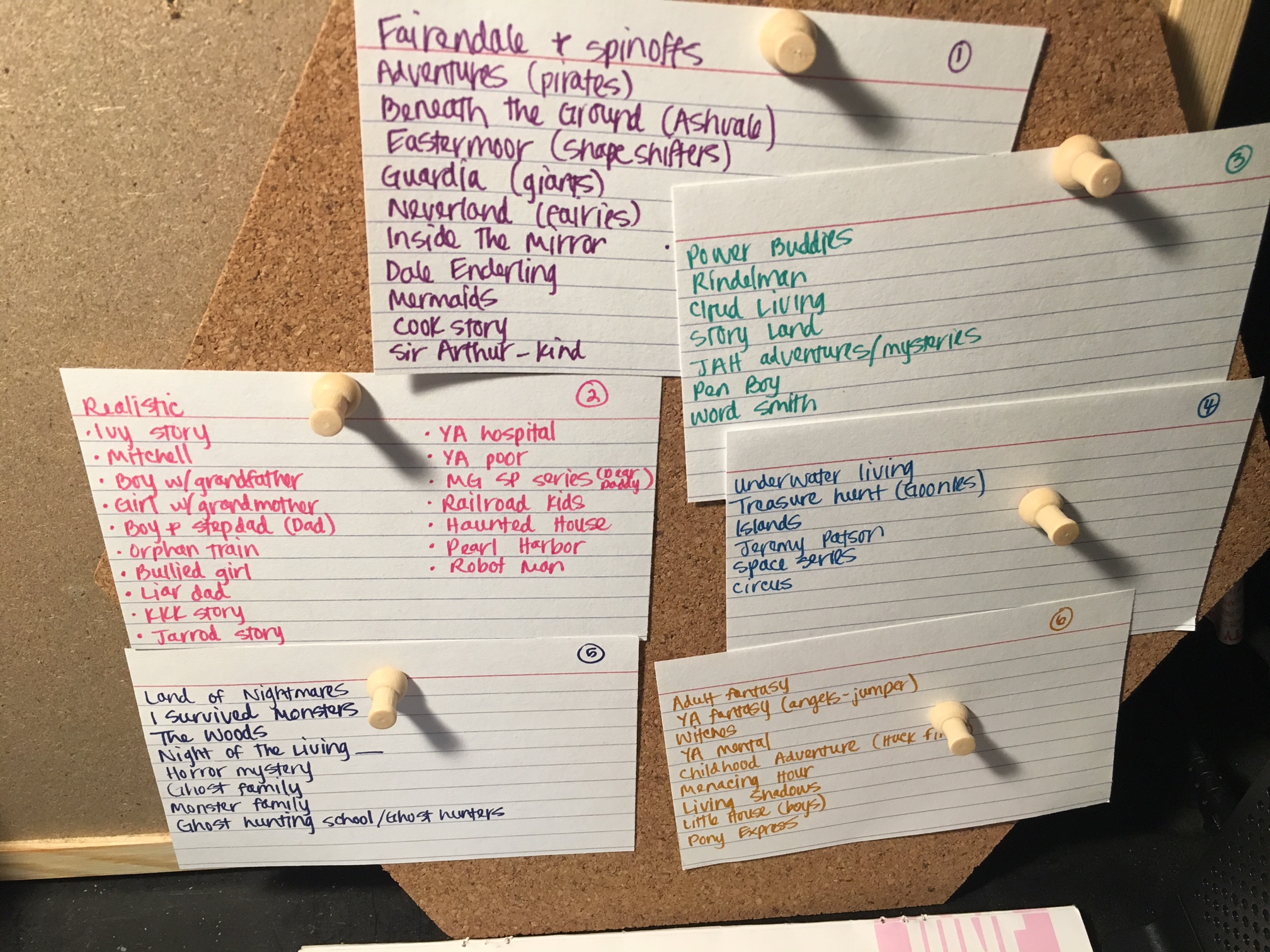

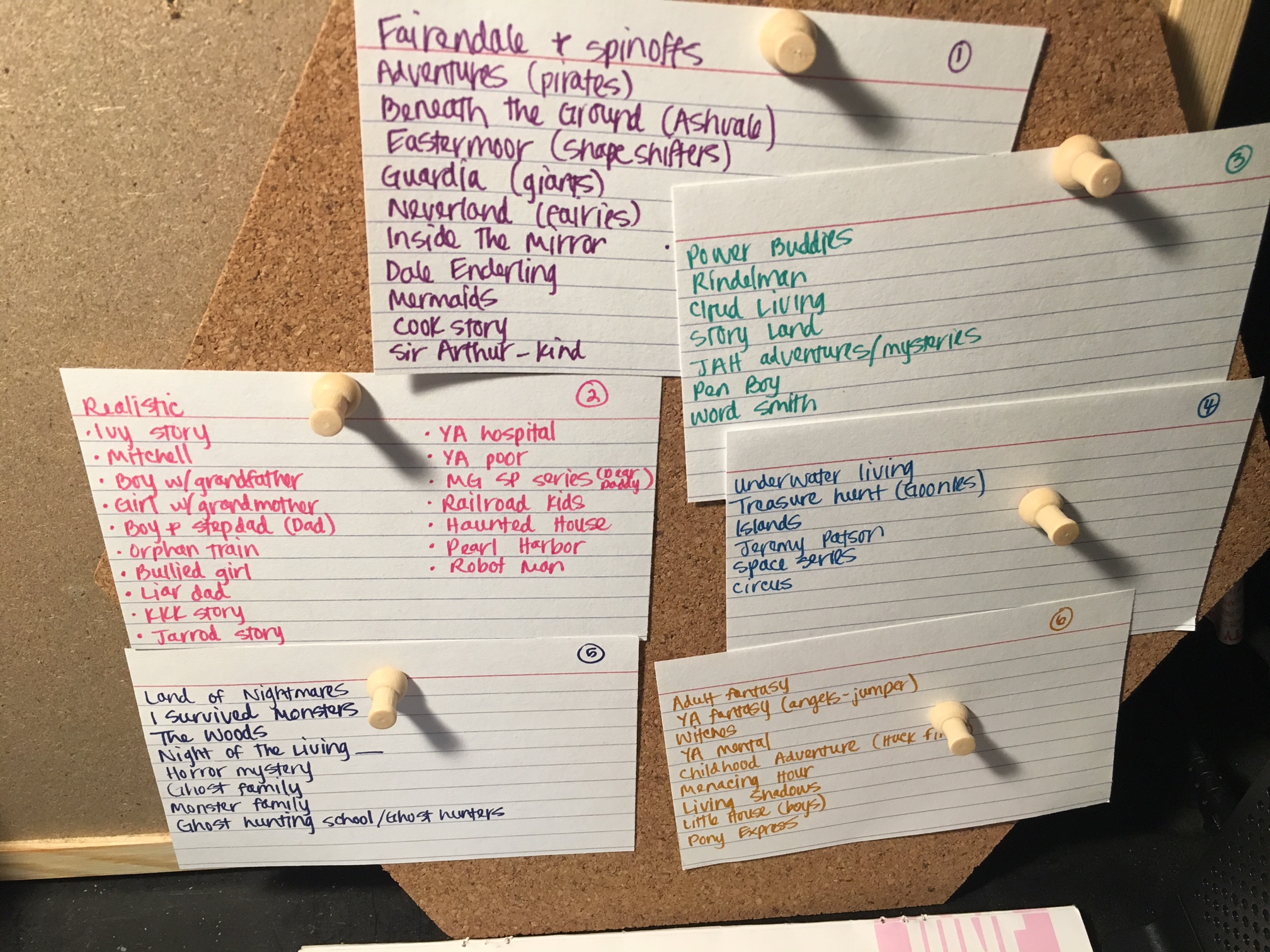

Last month I talked about the importance of capturing your ideas in some way or another. I use index cards to jot down every idea that visits me, and that has worked well for me. It’s up to you how to capture them; it’s only necessary that you do.

But what happens to those ideas once you’ve captured them?

Again, you’ll have to find your own way through this (you might be more digitally oriented than I am), but I use a system of multiple photo boxes. Multiple stories are collected in each box, and each box is assigned a number. I have a key that tells me which story corresponds to which box.

The challenge, for me, is that I am never only working on one story at a time. I have so many ideas that are always working themselves out in the background, which means I need to have a system of, for example, collecting poems I read that might be brainstorm material for a story I write years from now. Or remembering a location that sounds interesting but doesn’t have a story yet. Or recording a character I want to write whose story I have not yet heard.

These boxes keep all of that safe and somewhat organized (about as organized as I can get).

I keep the boxes in my closet, and when I am ready to begin the long work of a story, I take out the box, examine all the notecards that I’ve collected, and begin on the research and brainstorm portion a few steps ahead.

This capturing system works well for me, although my husband complains that our closet doesn’t have enough room for shoes anymore. Who needs that many shoes?