by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings, Wing Chair Musings featured

We all gathered on the same two acres where my sister and brother and I grew up, though the house we lived in for seven years no longer sits on the land. Another marks its place instead: wider, longer, newer.

Fajita meat smoked on the island in the middle of the kitchen. A bowl of my mom’s potato salad hugged the edge of the counter, a metal spoon jutting out of it. A cake, frosted in white, covered in candy mustaches, bleeding red along the sides, waited to be cut.

It said, “Happy Father’s Day.”

I’m not a cake person, but my eyes would catch on those words every time I passed by the island. Happy Father’s Day, it said. Happy Father’s Day.

All day long I felt something pinching at the corners of my existence. All day long I shoved it back down where it belonged, hidden and safe in a heart that had come to terms with this, truly. All day long I tried to forget about my rocky relationship with the word “father.”

But it’s not something a fatherless child can so easily forget.

///

My memories of my father, especially the first ones, are vague and hazy and uneven. I remember looking up to him and marveling at how tall he was, like a giant. I remember watching everything he did with awe and adoration, like he was the very definition of a hero. I remember how he smiled, his eyes crinkling up in a way that made you want to do whatever you could do to elicit another, because they were so few and far between.

I remember hands that would hold me when crossing a road, so I would be safe, and hands that would redden my skin in successive smacks for crying harder when he threatened to give me something to cry about. I remember tall glasses of milk with butter biscuits and the mess of a kitchen my mom would have to clean up after my father decided to cook. I remember a bright yellow truck and swimming in a murky lake and words that could sting worse than his hands.

I remember standing beneath a cover of trees, the wind pulling at my dress, whipping it against my knees and calves, while he climbed on the back of his motorcycle. I asked him when he would be back. He said nothing, only smiled, blew me a kiss, and drove away. I watched him until I could not see that motorcycle anymore, until I could not see him anymore.

And then I remember gone.

///

At my mom’s house, the fathers stood around outside, talking over a barbecue pit. They chased little ones inside, saving them from plummeting off a couch. They bent over a game of croquet and taught boys how to putt.

Midway through the day, I ambled outside and saw my brother-in-law, leaning into a tire swing, helping my niece onto it. He pushed her in gentle circles, and she giggled. She asked him to push her again, and he did, this time higher. Her face changed, and her hands wrapped tighter around the rope. She made a little noise, startled by the feel of flying higher.

He heard the noise and stopped her, reassuring her she was safe. She climbed down and ran off across the wide yard. His eyes followed her, and, when her face grew too red and sweaty, he carried her inside for a drink of cold water.

I watched, and I wondered.

I wondered what it would have been like to have a dad who noticed. A dad who noticed that your face changed almost imperceptibly, because you were trying hard to be brave, but the truth was you were scared. I wondered what it would have been like to have a dad tell you it was okay to be afraid, that he still loved you even though. I wondered what it would have been like to have a dad who saw your thirst and met it.

My dad noticed the shortcomings and the mistakes and the journal he once took it upon himself to read. He told us all the ways he would have raised us differently if he’d been the one to keep us, instead of our mom, who, he said, coddled us too much. He saw our thirst and called it complaining. Neediness. Weakness.

Ridiculous. Inconvenient. Too much.

The words needled into my skin, becoming three completely new ones: Not. Good. Enough.

///

It took him a long time to come back, but he did. He came back and then he went away again, and then he came back and went away again. After a year of his being gone, my mom told us we were moving.

To Ohio, she said.

To be together, she said.

Like a real family, she said.

We cried and protested, and when the crying and protesting didn’t work, we despaired and hated. We didn’t want to leave our friends, our home, our security. We’d never even been out of the state of Texas, but we went in the end. We had no other choice. Being a real family was too alluring.

My mom settled us into the largest house we’d had, or at least that’s how my memory tells it, even though I can’t remember the rooms all that clearly, because a veil dropped over my memory that year, as if my life had been a candlelit movie set until a move to Ohio turned it into a darkened theater, with only flashes of clarity.

But what didn’t happen in the Promised Land was my father coming home. We weren’t a family. Nothing changed.

My father’s absence in that year carved a jagged hole in my heart. I tried to be the best I could be, so he would come home. I tried to make the best grades, tried to have all the right friends, tried to be perfect, tried to be less of an inconvenience, tried to prove I was worthy of love. But nothing I did could bring him home.

We left Ohio with failure whipping across our backs, and I would work harder in the years that came after, always trying to prove I was somebody. Somebody great, somebody noteworthy, somebody who deserved a loving father who stuck around.

The harder I worked, the larger the hole grew and the larger the hole grew, the harder I worked. It was a cycle that could not be tamed.

I fell fast and furious into it.

///

I was a seventh grader when my stepdad showed up at the front door with two large pizzas and met us for the first time. He was a young blue-eyed buzz-cut-haired man who treated my mom like she was something special, and as much as we loved that about him, we could not forgive him, at the time, for taking my father’s place. And we made it hard on him.

We shouted our disrespect, and we fought with our hands and our hearts and our words, and we told him we didn’t want him to live with us, never ever ever. We did everything we could think to do to make sure that our father’s space was untouched. Saved, if you will. Because our father might one day return.

It’s hard for a kid to let go of that dream. It’s hard for a kid to let another man step into the place of one who should have loved them unconditionally, recklessly, forever and always just because they shared his blood and genes and the long legs and thin lips and straight hair.

But my stepdad stuck around. He fought for our hearts. He picked up all the pieces my father left and said we could be his. We could be loved. We could be good enough.

My stepdad walked me down the aisle, and he sat in the waiting room the day all my sons were born, and he calls my sons his grandsons, even though they share none of his blood. He has shown me what it means to be a father. It does not mean abandonment and forgetting birthdays and wishing out loud in the hearing of a kid, that the kid could be different.

It means putting a heart back together with Duct tape and calling it spectacular anyway.

///

My husband is one of the most hands-on fathers I know. He cares for our children for half a day every day while I hole up and write. He plays with them, he raises them, he speaks life into them. I watch him sometimes with a mixture of love and awe, because I never knew that a father could be like that. So present. So forgiving. So involved and heroic and wonderful.

I never knew a father’s love could be so spectacularly life-changing—not just for the ones who are the recipients of it, but for the ones who are watching it unfold around them.

A father, in my world, had only ever picked up and left, moving on to another family—one that was better, easier, more worth the work of sticking around. But healing crept into my heart, watching my husband. Not just because he was a phenomenal father but also because he messed up.

He messed up. My father messed up. We all mess up.

A father has a tough job, this being a hero to the ones who look to him for truth and love and identity. Some fathers aren’t up for the task. Some are. Some try. Some don’t so much. Some step into the role and play it for all it’s worth. Some are too afraid to even toe it.

And some? They just don’t even know where to start.

///

Father’s Day. It’s not an easy day for me. I always feel a bit guilty that I only really call my father once a year, on Father’s Day. Sometimes I don’t even do that. Sometimes it’s just a text. Sometimes the whole day goes by and I’m so busy with my husband and boys that I forget to even text.

Part of the problem, see, is that my father is not the first person I think of on father’s day. I think of the man who stuck around when the going got hard and I turned into a contrary teenager. I think of the man who stood there, stoic, when I called him an idiot because he wouldn’t let me go see my boyfriend. I think of the man who spun me around the dance floor during the father-daughter dance the day I got married.

Father’s Day isn’t always a simple day in the lives of the fatherless ones. Some of us have blood fathers who gave up and called it quits, and that damaged something deep inside, told us we weren’t worthy of the effort it takes to be a dad. Some of us have fathers who left in other ways, like death or suicide or an accident that rendered him inaccessible to us. Some of us never even knew our dads.

We were hurt by our dads. We still carry the scars. Maybe we haven’t quite forgiven them.

And so when it comes time to celebrate dads, we say, oh, well, it’s just another day in my life, because I never really had a dad anyway.

But there is something I have learned in the years between that vulnerable eleven-year-old and this woman I am today, and it is this: Dads come in many different shapes and sizes, and the ones we think of on Father’s Day aren’t always the ones who scientifically contributed one half of who we are.

The fathers of our heart look like teachers and coaches and friends’ dads and stepdads and fathers-in-law and mentors. They look like the ones who step into our lives when others step out. They shape us the same as any dad should, even though they didn’t have to. They fill us. They rebuild us. They are dads.

And so, for Father’s Day, I choose to thank all those men who step into the lives of the fatherless ones and teach little boys how to be men and little girls how to be loved. Thank you for your presence. Thank you for your generosity. Thank you for your love.

Happy Father’s Day to all the fathers of my heart.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by This is Now Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

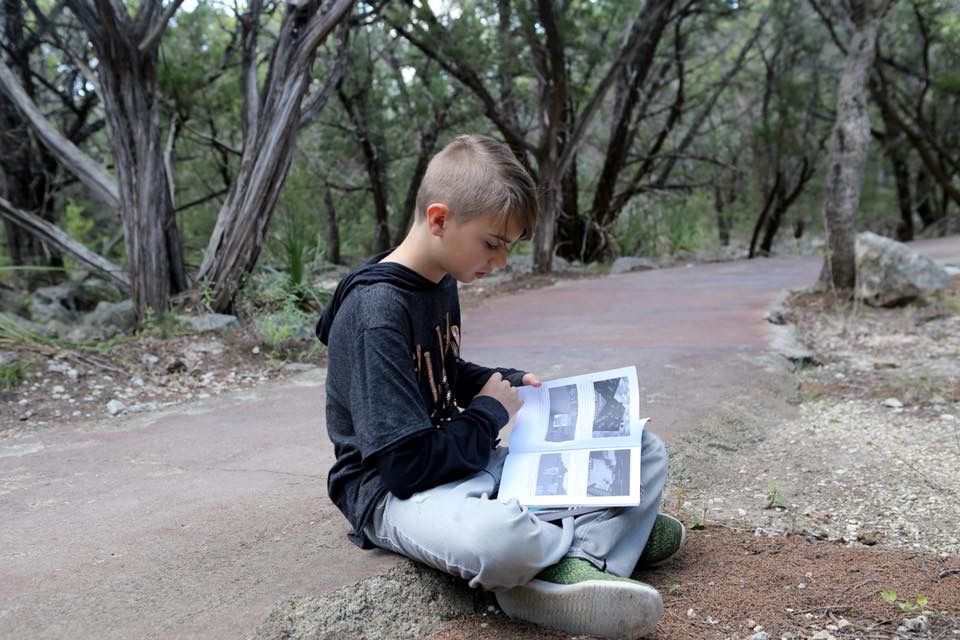

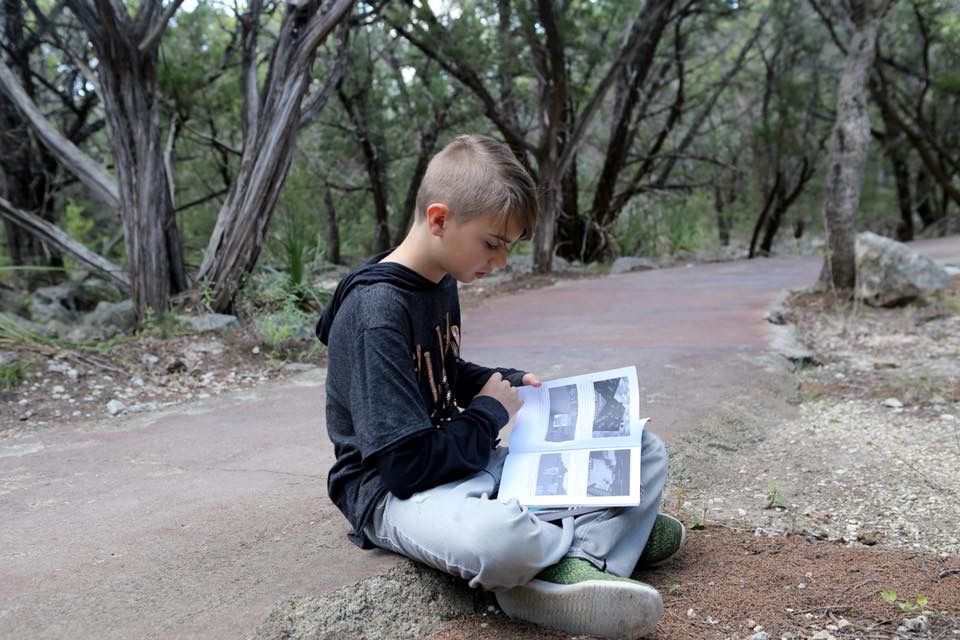

Every Wednesday night, my oldest son and I have what we call “Snuggle Time.” It’s a sweet time—about fifteen minutes—when he gets to have my undivided attention—which is a precious rarity in our home.

The last two Snuggle Time sessions he’s wanted to go for a walk—just up to our mailbox and back.

The other night, the moon was nearly full. We stepped outside our house, and there it was to greet us, looming in the black sky, the stars around it hardly visible because it was so bright. For a moment, a cloud passed over it, turning it hazy, like a glowing orb, a little other-worldly.

“Look at the moon,” my son said. We stood there for a few minutes, admiring this spectacle of the universe, which put on a lovely show, as though it knew we were watching. Then we continued on our mission: to the mailbox.

My son slipped his hand in mine, and we walked, side by side, step matched to step, the keys jangling in my other hand. He talked about what he wanted to do for his elective next year, when he enters middle school. I listened. I breathed. I saw.

Click. The stars peering out from behind clouds, pulsing a song we could not hear.

Click. The neighbors’ cars, shadowed, shining after a thin blanket of rain earlier this evening.

Click. A cat stealing across the driveway.

We joked about what we would have done if the animal skittering across the driveway had not been a cat—a skunk, perhaps, or a raccoon or a zombie. (We would have run, of course.)

We were back at the house much too soon, so we stopped again, peered up at the moon, still as lovely as before, his hand still in mine. The insignificant mail shared space with the keys in my other hand. My gaze kept turning back to that brilliant moon, as if something waited for my notice. For my listening.

And I heard it: the earth sang.

The earth is always singing, I think. It may sound a bit mystical to say that, but I agree with John Keats: “The poetry of the earth is never dead.”

And it has something to tell us if we take a moment to listen.

That night, it said, “Linger for a bit. Enjoy your son. Be here, now. Nothing lasts forever.”

So I lingered. After the timer clanged, startling both of us in a way that made him laugh hysterically, I took an extra minute—two, three—with my son.

Time never lasts forever.

I hope that as you move about your month, this last month before school is finished, perhaps, and your children move up yet another grade; this last month before the stretching out of summer, when you take a vacation or two and enjoy friends, family, or a lighter approach to work; this last month of endings and new beginnings, you will linger. I hope you will take a moment or two or three with the people you love, to say, I am here and you are here, and life is lovely, isn’t it?

I hope you will listen to the poetry of the earth.

(Photo by Helen Montoya Photography.)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I was stirring some oatmeal, having already ruined a pot with cayenne pepper when I mistakenly grabbed it instead of the cinnamon. I was still getting over the flu, and my brain wasn’t exactly firing on all cylinders.

And, because my brain felt foggy and unfocused (or, perhaps, in spite of it, though my life often feels like a tapestry of irony), my second son chose this morning to ask me, “What makes people be mean to each other?”

I turned down the burner, knowing that this question would take all of my attention to answer. I stirred one more time before turning around to face him. I said, “What makes you be unkind to your brothers?”

He shrugged.

“Sometimes when you feel angry, are you unkind?” I said.

His eyebrows went up. “Oh, yeah.”

“Or if you feel sad, sometimes you say something unkind, right?” I said.

“I think I understand,” he said. I could see that he was thinking, turning over my words in his mind. I wanted to add another important thought.

“People aren’t usually unkind without having a reason. They feel sad, they feel angry, they feel disappointed, they feel lonely. Those feelings are hard for them to feel. They’re hard for any of us to feel.” I looked at him to see if he was still listening. His blue eyes fastened on me, like he waited for more. By this time, his brothers had joined him at the table, and they were all listening.

“Sometimes people choose unkindness because they think it will make them feel better. It never does,” I said.

My son shook his head.

“We should always work to figure out why people are being unkind,” I said.

We’ve been telling him and all his brothers this very thing since they were all too young to understand it. In fact, it’s hidden in many of our family values: believe the best about people and seek to find out why they make the choices they make. Don’t judge. Accept, embrace, and help heal their hurts.

Love the unlovable. Find the lonely and make them feel full. Defend the defenseless.

They can hear the shift in our voices when we talk about these things—the slight hitch in our breath, the upward turn of our tone, the urgency of words and sound that fly straight from our hearts. They know it’s important—no, vital—to listen.

When I turned to stir the oatmeal, it had burned a little on the bottom.

But no one complained.

(Photo by Brooke Lark on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

It’s the last week of school, and I am a weeping mess. It’s not a sad weeping, really. It’s a bittersweet weeping, a proud weeping, because every step they take on this road that is education and growing up and moving on is another step they take out of my home.

Those heartstrings tied to them want to pull tighter, shelter them from the heartache I know is coming, because it always does. I want to protect them and hold them and keep them.

Mostly I want to keep them. Keep them small. Keep them safe. Keep them here. And yet this week has reminded me that keeping them is not something I can do.

Two days ago I watched my eight-year-old walk the stage for his second grade completion ceremony, where he got the “Artful Artist” award. Yesterday I watched my six-year-old sing and sign and accept the “Best Reader” award during his kindergarten completion program. Today I watched them both dance their way into summer.

Or I tried. It was hard to find a window between hands and arms holding video cameras and smartphones and iPads where I could actually see them. I ducked and turned and moved, and everywhere I went there was another device recording the moment. I had to squint and tilt my head just the right way to see my sons.

At first I felt angry. Annoyed. Because I was a parent, too, and I deserved to see my sons bust a move just like the next person did.

And then I remembered: It wasn’t so long ago that I did the same.

///

Two years ago, when my first son was a kindergartener, I stood in the throng of parents and tried to take a video of him dancing, because his daddy wasn’t able to come and his daddy needed to see, but mostly because I wanted to keep the memory forever and ever and ever. The whole time my Canon 7D kept slipping away from him because I was trying to watch him in person, not on a screen, so the video isn’t even a very good one.

I watched him stand on his tiptoes waiting for the music to begin and I watched him strike that last pose and I watched him walk away with a grin I could barely make out on the screen of the camera. I could not see that grin shine. I missed the way he made a goofy face at his brothers in the crowd and made them all burst out laughing, because I was so intent on getting the perfect shot. I missed the way his feet fairly flew off the blacktop because he was so excited that he’d nailed the dance. I missed looking into his eyes and letting him see the pride that shouted from mine.

I missed. And to this day, I wish I had the vision in my memory store more than I had the video on my computer’s memory store.

When my boy got home from school, he didn’t even ask to see the video. He didn’t care that there was one. He only talked about when he had done that jump move and did I see him throw some break-dancing into the free form section? And I had to admit, at least to myself, that no, I hadn’t seen it, because I was too busy trying to capture video.

I missed.

///

We miss something in these moments we work so hard to preserve. We miss the living of them.

It takes us a while to see it, because we are the first generation of parents growing up in a world of technology that puts access to video at our fingertips, without having to set up the perfect shot or figure out the best lighting or get as close as we possibly can. We have zoom lenses and autofocus and cameras that can take five pictures per second.

And everything feels so necessary. I know. I felt it this year.

I purposely decided, before each of the school events, that I would not pull out a video camera this year. But when the second graders walked across the stage for their completion certificates and awards and the principal announced that the center aisle of the cafeteria was reserved for parents taking video and pictures of their kids, I wanted to get up. And when my son stood with his teacher and turned to the center aisle and no one was there, I felt like I had let him down. Like I had lost an opportunity. Like I had willingly given up recording a significant moment. But I just waved crazily from the back of the cafeteria and called his name and let that grin of his slide all the way down into the deepest places of my heart.

You see, our kids don’t have to know that we are recording their every step and capturing their every accomplishment and putting it all into a folder they won’t really care about when they’re eighteen. They just need to know we’re there. Watching. Enjoying. Marveling. It’s hard to watch and enjoy and marvel with a phone between us and every special moment. Sure, we may get to savor it later, but what are we missing right now, in this moment here?

There are some things pictures can’t capture.

The excited glow of his eyes. The way his smile lights up the whole room. How he grins even wider, if possible, when he catches your eyes and not just the camera’s eyes.

I understand how we can get caught up with every significant moment and want to keep it. Keep them. I know what it’s like to feel like you probably should order a class picture and those individual school shots, even though you take a billion better ones at home. I know how a yearbook in elementary school can feel necessary, because how will they remember if we don’t find a way to preserve those memories?

The thing is, they don’t really need our help remembering what’s important.

///

My kindergarten year is hazy in my mind, but I remember balloon letters hanging from a ceiling and a gather-together rug in the middle of the room and a claw-foot bathtub in the corner where we took turns reading for pleasure. I remember blue mats on the floor and lying down too close to a girl who picked my chicken pox scab while I was sleeping and made a scar in the middle of my forehead. I remember pronouncing island like is-land and how Mrs. Spinks corrected me. I remember a playground with metal seesaws and above-ground culverts painted yellow and tractor tires cut in half. I remember losing a tooth in a Flintstone push-up popsicle and my brother choking on a chicken bone, back when the cafeteria chicken noodle soup was made from real, bones-included chicken, and the first time I slid down the metal slide in shorts and burned the backside of my legs.

My mom didn’t have to capture any of those moments for me to remember them.

There is something magical about remembering our pasts the way our minds want to remember them. That kindergarten reading bathtub probably wasn’t as pretty as I remember. That metal slide probably wasn’t as tall (or safe) as I remember. The cafeteria and gym and schoolyard probably weren’t as large as I remember.

And part of me is glad a video doesn’t exist to prove my memory wrong.

///

Memories are so much more than seeing. They are hearing and feeling and smelling and tasting, too, and a video can only catch two of those. Our memories can catch them all.

I record so much of my kids’ lives. When they do something funny. When they wear something cute. When they sing one of their original songs or choreograph an amazing dance or write a play and perform it for us in our living room. I record because I want to remember.

But could I remember without the help? Will I remember how he moved his hands in that funky way during “Uptown Funk” without a video camera preserving it forever? Will I remember the hilarious poses he struck during the freeform part of the dance? Will I remember the way my other son tipped his head and made his body so fluid and waved his hands at just the right times during “Surfin’ USA”?

I’d sure like to try—because I want to be present in the moment. Right here. Right now. Looking at them with both my eyes open. I want my boys to know what it means to be fully present in a moment, to soak it up and let our memories do their work.

“Are you disappointed that we didn’t get a video of your dance?” I ask my eight-year-old when he gets home from school today.

“No,” he says. He grins. “I saw you dancing along.”

He knows the truth of it.

A mama can’t dance when she’s holding a camera.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Mattias Diesel on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

So much of what I do, as a mother, goes unseen. I plan our healthy meals and read the labels of everything I put in my shopping cart, to make sure our home stays toxin-free, and I mix our own cleaners and make note of when we’ll need to reorder those essential oils we use for healing. I carve out a schedule that protects our family playing time, and I craft a budget that means we have food and shelter for another month, and I make sure all the art supplies stay stocked.

I manage Amazon subscriptions for ingredient-approved vitamins and count them out every single day and line them up next to my boys’ breakfast plates, and instead of “thank you” I hear about how they didn’t want these scrambled eggs this morning because all their friends get to eat cereal for breakfast, and why can’t they? I clear out their closets when their old clothes are too small, and I buy them new underwear when the old ones cut off circulation and I stock new socks when the old ones have too many holes, and the only thing I hear for it is how they wanted red socks instead of the black ones I bought.

I turn off lights and flush toilets and mend their blankets and remind them to brush their teeth and find their lost library books and read stories until my throat hurts and send them back to bed a thousand times every single night, and I don’t even think they notice.

There are so many days I can feel downright invisible.

Welcome to being a mother.

///

When I was eleven years old, my mom slapped a magnet dry-erase calendar on the front of our white refrigerator.

“Dish schedule,” she said.

Our names were written on it in black—Jarrod, Rachel, Ashley, and Mom switching places on all the squares. Every month she sat down with a school calendar and the dry-erase one and wrote our names on the schedule in a way that wouldn’t interfere with our lives.

The schedule got more complicated when we got to high school, because there were volleyball games and every-night-of-the-week practices and football games with the marching band and National Honor Society and Wednesday night church and homework after all that.

I didn’t appreciate all the hard work that went into a schedule as complicated as that. All I did was resent that I had to wash dishes two nights a week. I resented that I worked so hard at school all day and then slaved away at volleyball practice and rode a bus to the pick-up point and finally got home after dark to finish what homework I couldn’t do on the bus, because I cared about handwriting and the bus was too bouncy, and then I still had to do the dishes.

So unfair.

My tunnel vision didn’t let me see that she worked all day, much harder than I ever did at school, and then she cooked dinner and tried to keep it warm for me and drove to meet the bus and stayed near while I finished my homework so I’d have help if I needed it and, on top of all that, she planned meals for the month and did all the shopping and budgeted our very limited resources and wrote out a schedule for doing dishes so one person was not overburdened with the responsibility.

She was a mother.

She was invisible, too.

///

Now that I have children of my own, I know just how selfish children can be. I know just how thankless motherhood is. I know how no matter what we do behind the scenes, there is still more they want us to do.

It’s simply the nature of children. I know this. They don’t see their own selfishness or the way those ill-timed complaints can make a mama not ever want to cook a hot breakfast for them ever again or how the mere thought of tackling eight loads of laundry that come back every week is enough to keep her in bed when the alarm chimes. They only wonder why they’re having oatmeal again when today was supposed to be pancake-day. They don’t see that Mama ran out of time to flip pancakes because she had to turn every male shirt right-side out before sorting it into laundry piles she’ll spend all day washing.

It’s completely, developmentally normal for them to not make those connections yet. Someday they will.

But someday means nothing for this day, this day I stripped all his sheets and blankets and spent half the day he was at school vacuuming and washing and putting a bed back together because he woke up with ant bites all over his legs and I’m afraid there might be ants in his bed because they were eating popcorn up here yesterday even though it’s against the rules. This day he comes out of his room complaining that his blanket is still a little wet.

This day when I loaded the washer with that first pile holding his Spider-Man shirt, because I was sure he’d want to wear it on his birthday, and there’s just enough time to wash and dry it before he has to leave for school. This day he comes down the stairs crying about how he can’t find his workout clothes to wear on his birthday, and I know they’re lying at the bottom of another pile I planned to wash later today.

This day I woke up to find three lights left on all night and I can’t help but mentally calculate how much that’s going to cost me.

The promise of someday does not make this day any easier.

///

After I married and had an apartment of my own, my mom came visiting with a box.

“What’s that?” I said, because I had recently finished unpacking, and I hadn’t missed anything important.

“All your old stories,” she said.

“What stories?” I said.

“The ones you wrote when you were little,” she said, and she pulled out one that imagined what I would do if I had a million dollars. I’d written it when I was seven.

“I’d buy a car, and I wouldn’t share with my brother,” I’d written. We laughed about it.

There were Little House on the Prairie imitations and the story about a girl miraculously walking again to save her friends from danger and another scrawled out on notebook paper the summer I went to visit my dad.

“I didn’t know you kept all these,” I said.

My mom smiled. “Of course I did.”

Of course she did. They were pieces of me she loved. They were pieces that proved her love.

And she is a mother.

///

There is a drawer in my closet where I keep my kids’ drawings and old writing notebooks they’ve filled with words and loose papers with quirky doodles filling corners. My boys don’t know the drawer is there.

My eight-year-old doesn’t know that when he slipped his note under our bedroom door, the one that bears a picture of a boy with a red face and smoke coming out of his ears and the words, “I feel angry when you tell me it’s bedtime,” the note went into that drawer. My six-year-old doesn’t know that when he wrote a kindergarten essay in school about how he knows his mom loves him when she reads to him, his essay went into that drawer. My four-year-old doesn’t know that when the amazing fox picture he drew disappeared from his drawing binder it went into that drawer.

They don’t know all the ways I love them, because they are still young children who believe love looks mostly like hugs and kisses and sweet snuggles. They don’t know yet that it actually looks like time and service and invisibility.

What I am still learning in my mother journey is that sometimes the greatest acts of love are the ones that whisper instead of shout.

A storage container with writing treasures shoved under our mom’s bed.

A dish schedule that honored our time over her own.

A ride to early-morning volleyball practices, even though she worked late.

I want to be that kind of great.

Indignation comes welling up in me, every now and then, when I’m tired and frustrated and annoyed that I can’t seem to find a single minute to myself. I want to be noticed. Acknowledged. Appreciated. I forget that invisibility is better than alone.

I get to be a mama. I get to love my children through olive oil brushed over broccoli and a sprinkling of sea salt sitting on top. I get to love them by joining them at the table and coloring a picture of Lightning McQueen, even though a thousand other responsibilities are calling my name. I get to love them with a secret drawer that holds treasures more valuable than what sits in our bank account.

I get to be loved by his bursting into the room while I’m working so he can give me a missed-you kiss. I get to be loved by the flower he brings me, because its beauty reminded him of me, and I get to watch it curl up while I’m writing. I get to be loved in his request to be carried downstairs, just like old times, even though he’s so much heavier now and, also, fully capable of walking himself.

I get to be loved in a million silent ways, and I get to love in a million silent ways.

Welcome to being a mother.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

The other night, my husband and I watched Dead Poet’s Society, a movie I remember loving in high school. I loved it just as much this time around. It is a phenomenal movie with phenomenal writing and acting.

But.

It struck me differently this time around. I’m a parent now. I cried—no, I sobbed—great, heaving sobs—when a boy is so beat down by the box his parents put him in—telling him who they expect him to be, what his career choice will be, what he absolutely cannot do, which happens to be his passion—that he has little freedom to enjoy his life and be who he is. He feels stuck in a future of his parents’ making, and it holds nothing he wants or needs.

As a parent, I cannot see this movie without feeling the weight of this responsibility: to let my children be who they are, not who I want them to be.

It’s one of the most important things in the world. It’s the way we show them love. It’s how we teach them to be themselves—and not anybody else’s definition of who they should be.

We all maneuver through a time when the thoughts and opinions of other people mean something to us, whether those “other people” are our parents or our friends or our spouses or our brothers and sisters. Maybe those thoughts and opinions will always mean something to us, because we’re relational people.

But oh!—we should never, ever let them limit us.

When I was in college, I was. 4.0 student, but I got a B in my first creative writing class. In fact, my professor so disliked my poetry (he called it florid and melodramatic) that he scrawled on one of my assignments something along the lines of, “Probably not a future for you here. Meaning, in poetry.” He said pretty much the same about my fiction (he was not a nice person).

On Sept. 18, 2018, The Colors of the Rain, a novel written entirely in poetry, will be published by a reputable New York publishing house.

Maybe I’ll send him a copy.

I let his words stifle me for a while. I put down my fiction pen and picked up my journalism one. I wouldn’t change that choice, knowing what I know today, but I would change the way I let him bully me out of my dream, which was always to be a poet and a novelist. I thought, then, that the things people said about me defined me. They knew more about me than I did, I believed. They could see things I couldn’t. They were right.

They didn’t, they couldn’t, and they weren’t.

“They” can’t say what you get to be or who you are or even why you were put here on this earth. We aren’t made for someone else’s box. We are made for something far greater: our purpose. And only we can know that.

I have been called many things in my life, some of them unthinkable, some of them moderately annoying—for writing what I write, for choosing to have six children, for speaking out against judgment and hate.

I have never let these dishonorable, sometimes vile, always highly inaccurate names define me, impede my vision, or silence me from speaking what I must speak.

Neither should you.

Be your wondrous, brave, spectacular self. This day and every day.

(Photo by Daniel Cheung on Unsplash)