by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Every summer, it’s the same old thing. The school year creeps up on us, after more than two months spent playing together and resting together and just being together, and here comes my old friend anxiety.

I worry that they won’t have the right teacher. I worry that they’ll spend a miserable year wishing they didn’t have to go to school. I worry that they won’t find friends this year or that their friends from last year will decide they don’t want to be friends anymore or that they’ll be picked on instead of liked.

I worry about bullies and about their hearts and about their futures and about their health and about their safety and about how much they’re hydrating in a day and about what they’re doing in P.E. this afternoon and about desks pushed too closely together and about lonely lunch tables and about playground politics.

There’s so much to worry about when your kids spend seven hours a day in someone else’s hands.

So, teacher, please take care of my boys.

I know I’m not the only parent asking. In the last few weeks millions of parents released their kids to public schools. They watched their babies board a bus and turn to wave, or they watched those babies drive away, or they walked them down a sidewalk and hugged them so tight at their classroom doors. The children all get to you differently, but they all leave the same, sent off with that lump in the back of a parent’s throat, with those watery eyes we’ll try to blink away before our little one (or big one) sees.

Our babies will touch sleeves with other students and fill in the bubbles on math worksheets and breathe and slap colors onto a canvas in art, and it will all be new and exciting and wonderful and fun until it isn’t. It doesn’t take long for the first-day-of-school novelty to wear off, and that’s when those students need you the most.

I know it’s not easy. I know there are so many needs, so many hours, so many kids. I know there is only one of you, and sometimes it can get overwhelming. I know because I live in a home with six children, and I struggle on a daily basis to offer them the best version of myself.

I know it can feel like a lot of pressure on your back, all these parents looking to you to teach and train and mold their children in ways that line up with how they’re taught and trained and molded at home. But the truth is, teaching is a great responsibility. So please, take care of our children. They are easily broken, and they don’t often forget. They need someone telling them, even in their most unlovable, annoying moments, that they are still loved, that they still matter, that they are still worthy. A child who doesn’t believe he’s worthy won’t try all that hard.

I hope you remember, in those hard moments, that a moment in time, a moment of misbehavior, a moment of sass, does not tell the whole story of who a student is. There are a lot of wounded children out there, but you can be part of the healing. What an amazing privilege.

When they’re acting out, when they don’t know what to do with all their overwhelming emotions other than what they’re doing right this minute, the crying or the flailing or the screaming, I hope you know. I hope you see more than the inconvenience. I hope you try to figure it out instead of chalking it up to just who they are. Because their behavior is not who they are, not even close.

You see, I’ve got one of those children. One of those children who could read Harry Potter before he was 5 and yet did not learn to control his emotions until he was 8. But he had a teacher. She made all the difference.

And there is me, too.

I was a fatherless kid, a girl who missed her daddy, a girl who could find no worth in who I was because someone important had left me without a second look back. Or so it seemed when I was 10. Right on the cusp of womanhood, I took it personally.

But I had a teacher. Many of them. They believed in me. They whispered who I could be, and even when I could not believe it for myself, I could believe them. Sometimes that’s all it takes—a teacher’s belief—to pick you up and carry you through. They saw writer. They saw brilliant student. They saw that I could be so very much more than I thought I could be.

So they called out the brilliance. They called out the good. They called out the “can” in me.

There is something strangely beautiful about a teacher caring and believing and speaking honestly about what she sees and what he believes a student can do. Makes you want to do it.

My teachers called out the best inside me. And you know what? I did it all.

You have the opportunity to call out the best in your students, too. Even in the “bad” ones. Even in the “difficult” ones. Even in the ones who should already know this but just don’t.

Every kid need a teacher who believes. Might you be the one?

Oh, I hope so. Because there are so many students coming from places we don’t even want to imagine. So many students who need to know that someone besides their parents believes the best about them. So many students who need your help.

They will come to you, leaving their homes, their safe place or not-so-safe places, and they will step into the scary public school world. They will need you to guide them through the roaring waters.

Please take care of our children. Take care of their hearts. Love them with just as much love as you can call up from the wellspring of your heart. When they fall, please help them back up to a higher place than where they started. When they mess up, please remind them that everyone does, because there is no perfect. When they don’t know right from left or up from down, please be their compass and lead them toward truth.

Please keep constant watch and be fierce in rooting out problems and call up in them a desire to always do better. Teach them how to build their wings. Show them how to bare their hearts and their dreams and their gifts. (You can bet I’ll be doing the same.)

And then let’s watch them fly together.

This is an excerpt from Dear Blank: Letters to Humanity, which does not yet have a release date. For more of Rachel’s essays and memoir writings, visit Wing Chair Musings.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Tomorrow I will rise early and sit through reading and writing and praying and then I will steal down the stairs to prepare breakfast and then steal back up to kiss them from their beds and point to their chalkboard schedules. Tomorrow I will walk down a concrete sidewalk, my hand wrapped around the fingers of one and the hand of another, and I will watch the odd one out lag behind or run ahead, whatever his mood may be, because there are only two hands for three boys. Tomorrow I will take my time on my way to the building, half a mile from our home, where I will leave three of them this time.

This year another of my babies will join 125 other kindergarteners, on his way out the door of my house and into the door of the world. And it doesn’t matter that I’ve done this twice before. Doesn’t make it any easier.

So I already know that I will join the ranks of other kindergarten parents, stopping at the door to watch their little big kid disappear into a world we have no control over, a world that doesn’t follow our rules or standards, a world that could be dangerous and terrifying and heartbreaking all at the same time.

It’s true that tempers at home, as we neared this day, have ramped up, and their daddy and I have looked at each other more often than not in the last few days with eyes that said, “I can’t wait for school to start,” but the truth is, I don’t mean it. Not at all. Because school starting means they are gone from me, gone from my encouragement, gone from my presence, gone from my protection. Never gone from my love, of course.

And then today the three who will go have climbed on my lap periodically throughout the day, like they know what this last day home means, and their snuggles have whispered loud and wild and desperate into a mama heart: They can’t go. They can’t go. I can’t let them go.

Because what if?

What if they don’t make any friends and become the outsider? What if they don’t like their teacher and their teacher doesn’t like them? What if the time they spend outside our home breaks their spirit or their confidence or, God forbid, their whole heart?

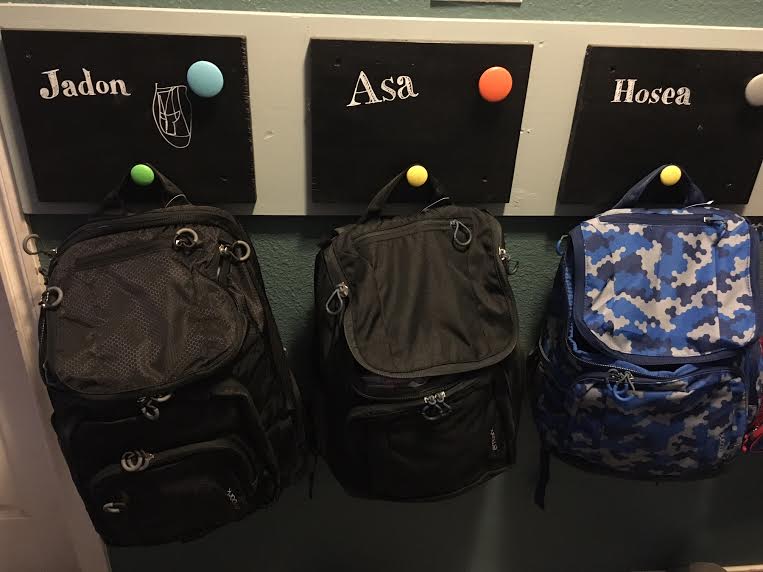

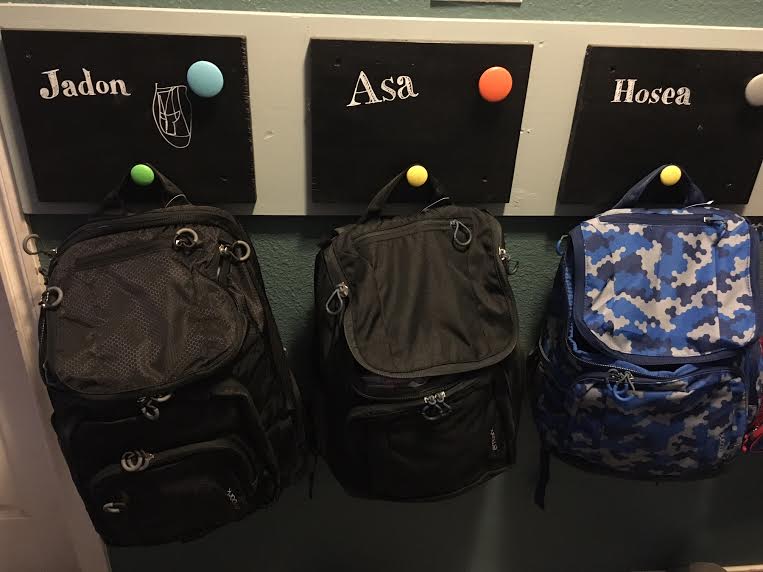

Tonight I will wander through the hallways of my home, like I always do, and I will touch those backpacks hanging on their hooks, and I will slip into their rooms to look at their sleeping faces, so big and yet so, so small, and I will cry and beg and pray that this year will be a good one; that this year they will know, without a doubt, that they are capable of wading through the raging waters of life; that this year they will really, really believe, deep down in the places where it matters, how important they are to me, to their friends, to the whole wide world, just the way they are.

I can tell them this every single days of their lives, but they have to learn it for themselves. Away from home. Out in the world. Somewhere else.

I know this. And yet it is not so simple, this letting go. I know what breaking feels like, and I don’t want it for my boys. I know what defeated feels like, and I don’t want it for my boys. I know what cruelty feels like, and I DON’T WANT IT FOR MY BOYS.

It sounds silly, I know, because it’s all just a part of growing up—the pain, the disappointment, the heartbreaks. Don’t I want them to grow up? Don’t I want them to be their own people? Don’t I want them to learn they can do it all without my constant help?

Yes. But no. I mean, yes. Yes, of course.

It’s just that yesterday he was only days old and I was just learning how to be a mother. Yesterday I was holding his hand, cheering him on as he put one wobbly foot in front of the other. Yesterday he needed me to bathe him and pour his milk and tie his shoes and pick out his clothes and tuck him in.

Where did the time go? Where did the baby go? Now they are only big, only tall, only lanky and self-sufficient and excited about this step outside the home, and I am only grieving. What does one do with this grief?

Well. I will fall apart, just outside their rooms, where I can hear them breathing in a sleep that feels far away from me this moment. Because it’s just so hard. So hard to watch them go.

It’s only one of a thousand steps. I know this. Theirs is a gradual leaving. I know this, too, but it doesn’t ever feel that way. It feels jarring, like we just weren’t ready, like we haven’t had the last five years to prepare for this day and the 12 first days after this one. (That last first day I try not to think about.)

Tomorrow I will walk them into this new step toward independence, and I will leave them in a place where they will learn about a world outside our home, where they will sit in classrooms with kids who can choose kindness or cruelty on a minute-by-minute basis, where they will watch their peers eat the cookies in their lunches first if they want.

Tomorrow we will stop just outside the doors of the school, where they will pose and their daddy will snap a thousand pictures for this momentous first day, and they will all smile so proudly, and I will weep so proudly, because they are my babies. Still. Forever.

And then we will walk to those classrooms, where two of them have done this drill before and one, well. One will turn at the door, and his eyes will ask that question, “Are you sure?” and I will have to make mine say what a mouth cannot.

“Yes, baby. I’m sure.”

Even though I’m not.

But he is ready. He’s ready to step out in independence. He’s ready to walk in the world. He’s ready to grow and learn and become his own person outside of me, and God it hurts, because he’s still my little one I pulled into bed with me those nights he didn’t sleep and I was too exhausted to sit up and feed. He’s still my little one I watched master the stairs before he even mastered walking. He is still my little one who hung upside down on the monkey bars before he could even speak complete sentences while I stood at the bottom with my arm-net stretched out, waiting for the fall I hoped would never come.

I am still standing at the bottom with my arm-net stretched out, waiting for the fall I hope will never come.

So I will let him go. I will let him walk in that classroom and greet his teacher, even though he probably won’t remember her name just yet, and I will leave him, and his daddy will squeeze my hand, because he knows just what this is doing to me, and we will walk back home with the three youngest who would fill a house for anyone else but make mine feel empty.

I leave him because I know he’s ready to try out those wings we’ve been building. I know he’ll crash-land sometimes and I’ll have to pick him back up and kiss those bleeding knees, but he will build mightier wings because of it. I know he’ll fly.

He will find his way into friendship, and he will learn the best games to play at recess, and he will love his teacher. He will be just fine.

He will be just fine.

Because he is stronger than I know. He is braver than I can even imagine. He is more than capable.

Tonight I will tiptoe into his room for one last look, one last touch, one last kiss on those dark lashes that only feel my lips in his dreams. And then I will leave, back to my room, back to my bed, where night will pull down the covers.

Tomorrow is a special day. Tomorrow my boy will make his first flight.

And I will be there, always, watching with proud tears and an aching heart.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Another of my boys starts school next week, taking that first step on a 13-year journey, and there are three of them now, away from my influence seven hours of every weekday, and I can feel the fear of it catching in the back of my throat.

It happens every year, just like this, and every year I have to fight off that failure-feeling that sneaks in—because I cannot be a homeschool mom.

I could protect them from so much. I could drill those values so deep in their hearts they’d never get them back out. I could speak life into their lives all the time, instead of relying on a behavior chart to teach them who they should be.

I could control their friends and their food and their learning and their choices and their decisions and their opportunities and their playground interactions and their exercise routines and their literature reading and their library visits and the soap they wash their hands with and the way people around them talk.

My heart has begun its jagged beating, once more.

I wish. I wish. I wish.

///

My first day of kindergarten I walked into a classroom not much bigger than a dorm room, lit by lamps and a back wall of windows. Mrs. Spinks hung all those alphabet balloons, an apple with an A, a penguin with a P, a zebra with a Z, in every corner of the room, and she pointed, three times a day, to the checkered carpet sitting in the center of the room, where we’d learn our letters and their sounds, even those of us who already knew how to read because our mama was a librarian and our 10-months-older brother had come home every day from his kindergarten year and taught us everything he knew.

My brother had refused to sit in that neat circle on a checkered carpet the year before, but I did everything I was told, eager to please in any way I could.

Just after lunch, the room transformed into a blue-carpeted mat, because we all stretched out our nap pads, and Mrs. Spinks would turn on that big noisy fan and all my classmates would sleep around me while I stared, wide awake, at those bubble letters, creating elaborate stories in my mind that linked them all, the zebras and the penguins and the apples and everything in between.

In that room we colored and slept and sat at desks facing a chalkboard with no computer anywhere in sight, and we were such a small town everybody’s parents knew everybody else’s parents, and we, the students, had already known each other for years.

It was safe. Comfortable. Warm.

///

Four years ago, when the oldest started school, the whole family walked him into a room with desks facing each other in pods and math sums arranged on posters and stacks and stacks of handwriting pages he and his classmates would work through by the end of the year, because all those 5-year-olds, or most of them, already knew their letters and just needed some extra practice writing.

My boy didn’t seem to notice that day the proximity of those desks, how they never gave a student one minute to be alone, but he would, in unexplainable ways, notice them later, when he’d yell at his brothers to leave him alone and when he’d cry about things he never cried about and when he’d fall asleep on our bed, even though he hadn’t napped since he turned 4.

I wondered, a hundred times, a thousand, if we had made the right choice.

But I worked a job, and that made homeschool a can’t-do option, and all those kids still at home, four of them, made it an even greater impossibility.

In those first days, I did what most first-time-public-school mothers do—I wrote a note to his teacher to explain my boy’s little quirks, the way he preferred to take off his shoes after playing outside because he wanted his toes to breathe, how he enjoyed teaching himself and read animal encyclopedias and Harry Potter and environmental guides, how he loves hard and strong and wild like a tornado that’s often overwhelming for those who are the recipient of that love.

I wanted her to know him the way I did, and I wanted her to accept all those quirks, all those strong-willed bones that hold a hard line in his body, and love him anyway.

And then we walked our beloved one to school and left him there, sitting in a seat that bore his name. I hoped all the way home that he would feel as safe as I did when I was just a 5-year-old girl in a world I had never known.

But you can’t make a teacher love a child, and sometimes the only safe place you can give him is his home-place.

I would learn that later, and it would drive another spear in my heart.

///

The kindergarteners in my small-town school shared a playground with everyone in school, just like we shared a cafeteria with one lunch period and one tiny hallway of classrooms.

Our playground didn’t look at all like the playgrounds of today. A merry-go-round and a metal slide and three seesaws edged it, and, in its middle, a bank of swings and above-ground culverts and cut-in-half tractor tires painted sky blue and electric orange and pale yellow, set upright for the climbing onto and under. A cement slab waited across the street for P.E. class, but we weren’t allowed to cross the street during recess.

That first day I stayed far away from the seesaws and the merry-go-round and the tires. I stuck to the swings, because it was what I knew, and I could kick my feet high and feel like I was flying for that half-hour of free time twice a day.

It was safe.

But as the weeks wore on, I watched friends climb through the above-ground culverts, where spiders hung from cement tops and snakes might be hiding in the grass patches between them—and if they could do it, I could, too.

A friend and I hid in one of those culverts during one recess, and there was a boy, years older, who stood just to the side of it. I knew who he was—a big boy who rode the bus home with my brother and me—by his scratchy voice.

Hey, Fatton, he yelled so everyone on the playground could hear. I peered out of the culvert, because the name sounded awfully close to my last name: Patton. He was pointing at my brother, just across the way, climbing onto a seesaw with a friend small and thin. You’re too fat for that, Fatton.

He wasn’t fat, my brother, just solid, built like a football player, but the name would stick all through elementary school, and that boy would be the torturer, and he would drag along with him other boys, boys who went to church with us and boys whose moms knew our mom and boys who came from good homes with a mom and dad who loved them and tried to raise them right. They would all tease and poke and tear apart.

It was that day I learned that school could be a not-so-safe place, one that could take a last name, Patton, and turn it into Fatton because someone thought it was funny and didn’t think through how it might brand a heart forever.

///

It’s not so different, this world where my sons will walk to school and sit in a classroom and play on a playground. And yet it’s so very different. Bullies existed back when I was a girl, of course they did, but we knew each other’s parents and we knew each other and we didn’t hide behind technology and computer screens and entertainment that existed outside of real relationships with real people.

We knew how to look our tormentors in the eye. We knew how to see that their mom was dying of some disease doctors didn’t know how to cure and how his dad worked too much and never spent time with him and how they were afraid of our brains and our dreams because they somehow believed ours stole something from their own.

My boys, though, are coming of age in a world that values performance over empathy, that holds up competitions as the only way to achieve, that mandates boys walk angry and wounded and shut down, because to show emotion is to be a lesser man, and they don’t know how to express their deepest hurts outside of the violence they see everywhere—in games, in movies, in their homes.

They will live in a school world where men can walk in and shoot 5- and 6-year-olds, where boys carry knives in the front pocket of their backpacks, where bullies on playgrounds can rip holes in a heart faster than a mama can mend.

How does a mama keep her sweet boys safe in a dangerous place like this? How does a mama make sure her boys keep holding tight to who they are in a culture that holds up who they aren’t as the “way to be a man”? How does a mama breathe on a day like today?

These are questions I cannot answer.

///

All the kids braved the monkey bars back when I was a girl, even though they were so high off the ground even an adult had to swing across instead of walking themselves across.

There was a day when I watched a boy, my brother’s best friend, get halfway across and then drop, his body twisting all the way to the ground, his hand trapped beneath him so it cracked in three jagged pieces. I watched him turn pale as the teacher on duty led him away, and I watched him return five days later with his hand and wrist wrapped in a white cast, ready to sign.

I watched a friend brave the big metal slide that burned our behinds raw when the sun was out, and she slid all the way down, her legs squealing for her, and then her bare-skinned thighs stuck to the bottom so she had to throw herself off, and the throwing knocked out two front teeth before they’d even had a chance to loosen. I watched her cry herself bloody as she ran off to find help.

And then there was another day, when we all sat in a cafeteria where the smell of chicken noodle soup shifted and turned and stretched, and I sat down with my friends and dipped my two cheese rolls in broth and ate them first, and then I heard the yelling, and there was my brother, turning blue, and Mr. Tegler, the district speech therapist, behind him, lifting and squeezing until that bone flew out of his throat and my brother sucked air like it was all he’d ever wanted to do. I watched his face whiten in the relief of breathing again when he thought he never would.

My brother could have died. He could have died. He could have died. That’s what I remember thinking all those days later, a childish sort of thank-you prayer. A help-me prayer too.

Because in a place this unsafe, anything could happen to anyone.

///

My sons could die. My sons could die. My sons could die. Every step closer to the school, I feel those weights closing in.

How do I protect their dreams from death? How do I protect their hearts from death? How do I protect their lives from death?

I could drive myself crazy with all these questions I cannot answer. I can twist and turn under that not-really-a-decision public school decision, all those fears it drags along beside it, and I can let its guilt nip my heels all the way through the halls to those classrooms, and I can feel its burden hanging my neck and dragging my feet and choke-holding my heart.

Or.

Or I can let them go, let them take this first step out of my arms, because there will be so many more that must be made after this. I can loosen my hold to their own capable selves, to a God who knows them better than I know them myself.

We are parents, and we will always hold them tight, in arms or in ragged raw, letting-go hearts, but there is Another who holds them, too, and as hard as this letting go is, we must remember they will be caught. They will be held. They will be loved.

I can keep them hidden and safe, or I can let them go to shine like noon in a world of midnight.

I can keep them within the bounds of my home and my carefully controlled community and my list of approved friends, or I can let them go to stand on legs of their own and live out values and missions and love in their own individual way.

I can teach them to crawl in my safe-zone perimeter, or I can let them go fly.

I want to be brave enough to let them fly.

So next week I will take the first step. I will swallow hard, and I will kiss them goodbye, and I will whisper those words into their ears, Remember who you are. Strong. Kind. Courageous. And mostly Son, and then I will walk the sidewalk back home, with three more who wait for this flying.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Today I had a song stuck in my head, one from Plumb’s CD Need You Now. The line from the song goes like this:

“But I’ve never felt this tied up and helpless/and all that I know is you’re gone, how do I let go?” and when I’ve finished singing it, I have this from my 4-year-old: “The singer wasn’t really tied up, was she?”

This began a discussion about how “tied up” isn’t always used in a literal sense, like the singer had ropes wrapped around her or something, but is sometimes an expression for feeling constrained by something, like how when Mama had the twins and they had to stay in the neonatal intensive care unit for a while and couldn’t come straight home with us, Mama and Daddy decided not to go anywhere far away, because we would be leaving half our children behind. Mama and Daddy were “tied up” by the twins’ need to stay in the hospital.

And then this, from my 6-year-old: “We tie you up, don’t we, Mama?”

It took me a while to answer this question because, in a way, yes they do. Becoming a parent changes everything. It changes even the most seemingly simple things, like how late you can stay out playing a gig with your band because kids have to be in bed by 8 p.m. so they can concentrate well in school tomorrow, and how writing that has to be perfected in a quiet space can only be attempted during sleep time in a house filled with five wild boys, and how date night frequency is proportionate to how many people are willing to watch five boys alone (not many, I can tell you).

But these constraints don’t make us feel “tied up” unless we expect something different.

This has been a gradual knowing for me. When we had one child, maintaining our lives and all the extras and that relentless pursuit of dreams was still relatively easy. Even two children didn’t change a whole lot for us. And then we had three, and suddenly we couldn’t find shoes when it was time to go and clothes mountains (clean, just not put away) piled up on our banister and bedtime became a two-hour power struggle. And then, in the middle of that drowning, add two more to the count.

I like my control. I like my routine. I like to know that I will be able to write between these set hours and no one will disturb me because they’ll all be quietly sleeping in their rooms like little angels, but reality sends one child knocking on the door because he needs to go to the potty and he can’t reach the light switch and it’s too dark to move the stool to where the light switch is, and then another knocking because he feels a little bit scared all by himself, and another knocking because I forgot one book that he needs for his quiet time.

But even in this, my hands don’t become tied until I let them become tied by my sour attitude and my too-high expectations and my ridiculous dreams of an alternate reality.

These words from Laura Markham give me pause: “Our children learn values by observing what we do and drawing conclusions about what we think is important in life. Regardless of what we consciously teach our child, he’ll understand and shape his values based on what he sees us do.”[1]

I hope my children learn by my actions that my values tangle tight around family and relationships and nurture. I hope they know inherently that they do not tie me up so much as they set me free from irrational expectation and perceived disappointment and most of all myself.

Here is where peace settles for today: Understanding that parenting changes everything. Accepting what it requires and how much it takes.

And then giving without restraint so we are living without constraint.

This is an excerpt from Book 8 of the Family on Purpose series: We Live Peacefully. Hopefully. Courageously.

[1] Markham, Laura. Peaceful Parents, Happy Kids: How to Stop Yelling and Start Connecting. New York: Perigee Book, 2012.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

Dear new mama,

Here you are, sitting in the dark, waiting for your husband to get home and relieve you, wondering if you can really do this, because it’s only been three days and you’re so worn out you can barely think straight, and just today you found yourself wishing you could go back to the way it was before, when you didn’t have a baby who woke up screaming in the middle of the night, when you didn’t have to worry about counting those wet and dirty diapers, when your body belonged to you and not someone else.

Yours is a great, big, scary world right now, because those nurses released this tiny little piece of you back to you, to take home and keep, and they did not ask if you were qualified at all, just put him in your arms and waved you on down the hall.

It isn’t easy, since nothing worth doing ever is, but these first days and weeks and months will unfold and so will your love.

You’ve thought a lot, these last few days, about the mess your body has become, and I know you want to change it right now, this minute. But it takes time. Don’t rush this weight-losing, this getting a body back, this fitting into old, pre-pregnancy clothes. It’s not a race, so stop worrying about what all those other mamas will think of your post-baby body. So what if your ankles are still swollen from the hospital fluids and your eyes are still puffy from the trauma of pushing for three hours and none of your clothes come close to fitting anymore, at least not yet (maybe not ever)?

You are beautiful anyway. You are. You have done magnificent and profound work, and you are beautiful beyond compare.

No one ever tells you that there will be days when your husband comes home from work and the house is pitch dark and the baby has finally, finally, finally fallen asleep in his swing after screaming in your arms for the last two hours; when you accidentally say out loud those words beating your brain: “Can we just give him back?”; when you’ll wonder how in the world you can be a good mother now, after thinking that way. So let me be the first to tell you: these days will come. But you are still a good mother, because they come for every mother. A baby is hard work all the years of his life, and you will not enjoy every single minute of every single day, so don’t expect to. You will not outrun the guilt that comes with those expectations, so just let them go. Let them go.

There are moments that make mothering worth it, but they are not all moments.

Stop comparing yourself to others. When your son will not sit docilely in a classroom when he’s 2, listening attentively to instruction like those other perfectly-behaved children, instead of running circles around chairs, it is not your failures as a parent. I know they can make you feel like it is, but this is who he is as a person, and the world will not be served by breaking him into a box.

When you choose to go back to work instead of staying home, this is not your love-lack as a mother. They can sometimes make you feel like it is, but I know the way your heart burns for your baby when you are away from him and how it burns for your work when you are away from work. Walking with a divided heart is not easy, but you will do it, year after year after year, because you love and you care and you dream.

In just a few days, you will rush your baby to the hospital for dehydration, because your milk never let down, and I want to tell you it is not your fault. You will carry it like it is, pumping every hour and feeding in between, because those lactation consultants said it could be done, and you will feel it every time those people lined up behind you at the store surreptitiously shake their heads at your choosing formula over breast milk. Those people who shame you, they don’t understand the pain of it, how you cried for days because you felt defective, how you grieved the losing of a bond they all say comes only by breastfeeding, how you wore this failure like an “unfit mother” brand blazing your forehead.

But it is not your fault. It isn’t. And your baby will be brilliant and wonderful and securely attached anyway.

Don’t worry so much about what all those others think. They don’t know you like they think they do. They don’t know your children like they think they do.

Stop trying to be the perfect mother. It’s okay to lose it every once in a while. It’s okay to make mistakes and admit those mistakes, like how you yelled and how you dishonored and how you pushed him out the door when he wasn’t moving fast enough and how you made him cry. It’s okay to think those thoughts sometimes, how you hate raising a strong-willed child, how you sometimes just want to do the easier work of breaking instead of the hard work of molding, how you never asked for twins so why did you get them. All of us, in our weak moments, think like this, and we should stop covering our shame, because we can never walk free bent in hiding.

Remember to celebrate yourself, the person you are becoming because of this baby. One day you’ll look back and say, certainly, that the person you are today, because of his grinding and cutting and chafing, is so much better than the person you used to be.

Don’t worry so much about the future. Enjoy each season for its colors and beauty and challenge. Seize the moments–don’t even try to seize the days.

Remember that “love is the whole and more than all” (W.H. Auden). It’s what matters at the end of the day, not how few times you yelled or how often you had to escape behind a closed bathroom door or that moment you regretted having a baby. Those moments when you hugged him so tight he couldn’t even move, and those moments you helped him build a ball track with 200 wooden planks, and those moments you read an extra story to him, they’re the moments he will remember most, not the raised voice or the missing mama.

You are an exceptional mother, even if you don’t feel like it. Ignore the world and be exactly who you are, because it is exactly who your baby needs you to be.

All the best,

Me.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I met you early in life.

I was just a girl. Just a girl looking for life. Just a girl looking for perfect. Just the right kind of girl for you.

You whispered your lies in my ear one night when a crack split right down the middle of our family.

Make him love you, you said.

Make him come back, you said.

Make him choose you, you said.

I did not know then that there is no easy answer for divorce. So I took your hand.

I skipped lunch that first day, sat out by the picnic tables with those friends who always brought their lunches so I didn’t have to smell the chicken noodle soup and cheese sticks inside the cafeteria. I forgot mine, I’d say when they asked.

The truth is, I was poor enough to qualify for free cafeteria lunches, poor enough not to have much in the refrigerator at home to even pack. But they didn’t know that.

They’d offer to share theirs, because we were all trying to attain the best body, even then, and maybe if we all ate the same thing one of us would not be skinnier than another.

No thanks, I’d say.

I was only 11, back from a year spent in a state 1,000 miles away from my home one, and now we were home again, except it was all different, all broken, because it was middle school where looks mattered, and there was no dad telling me I was beautiful, as is.

Would I have believed him anyway? I don’t know.

What I do know is that you made it easy to believe you. And once I did, you had me.

Our love affair began slow, with a stomach rumbling over lunch. But a stomach gets used to the hole after a while, and it didn’t take long before it just stopped talking about the better way I pretended didn’t exist.

You moved into the empty space. You gave me three years of skipped lunch, and then there was high school and early morning volleyball practice, and you threw out that innocent question: You don’t really feel like eating in the morning after those intense practices, do you? Wasting all those calories you worked off?

I started “forgetting” my breakfast at home.

There came a day, an early-morning tournament day, when a coach brought homemade monkey bread to give us an extra boost. I could smell the honey and the cinnamon, and it was all the things I loved most. She handed everyone a plate. All my teammates ate while I excused myself, left my plate on a counter and sat on the toilet until I was sure they’d all finished and I could pretend I’d forgotten where I’d set down my plate.

No one even noticed.

It was really too easy.

I had energy reserves. I told them eating right after an intense workout made me sick. I told them eating right before an intense workout—like the 12:30 p.m. athletics class—would make me sick.

I was sick. But no one knew about you.

Mostly because my mother saw me eat. My friends saw me missing. I didn’t waste away, because there was still dinner, however small it was. You and I covered all the necessary bases.

After graduation, when those stories started rolling in about the Freshman Fifteen, the extra pounds most freshmen come home with after their first year of college, my heart thrashed.

Don’t worry, you said. We won’t let that happen.

And we didn’t. Because college meant fewer eyes watching for when I should eat. It meant abnormal (or nonexistent) eating hours. It meant freedom to hold your hand and run away.

“Two hundred meals will be enough, right?” my mother said. “Two hundred fifty?”

“Two hundred will be fine,” I said.

I ended that semester with one hundred seventy-three meals left on my student ID card.

Mostly because you fascinated me. I enjoyed the me you carved from who I had been. The thin legs that had always been a little thigh-heavy. The arms that had always been a little tricep-flabby. The chin that was never as defined as I wanted it to be.

The new me was almost just a little bit maybe pretty.

So I let you keep doing your work. And when my college roommate noticed all my clothes sagging and dragged me to the cafeteria with her and the girl across the hall, I let your sister slip in for a time. We conducted our clandestine affair in the dorm bathroom, where I’d get rid of the chocolate cake and the mint chocolate chip ice cream and the pepperoni pizza and the enchilada casserole and the mashed potatoes with brown gravy and the buttered hot rolls with a stick of a finger or the swallow of a pill, even the night that cute baseball player came looking for me and I forgot my toothbrush.

That year ended and I came home not only without the Freshman Fifteen but without another twenty-five. I looked good. So I cut ties with you for a while, mostly because I lived with my grandmother that summer, and she cooked for me every night when I got home from my city job. I felt guilty not eating. And I couldn’t purge, because the living room was right next to the bathroom, and she would hear. She was smart enough to know. I could see it by the way she looked at me.

A year, two, three passed, and then you came back ready to play the summer before I got married.

I didn’t give up eating completely, because I was more interested in health this time around, but that interest in health didn’t stop me from packing my lunch of one cucumber and calling myself satisfied at the end of it.

“That all you eat for lunch?” a coworker once asked.

“I eat a big breakfast,” I said. Eight large strawberries was a big breakfast, in my book.

And then came marriage to a man who actually cared whether or not I ate and you and I lost touch for a time. You came to visit sporadically over the years, after the first baby, when I was appalled that my body did not immediately shrink back to its former acceptable proportions; after the third in four years, when baby weight stacked itself like it was going to stay.

After this last one and a broken foot.

It happens quickly, that sliding back into your arms.

I told myself it wasn’t going to matter this time. I told myself I would be unaffected. I told myself I was better than you.

And yet the six-week scale told a story I didn’t want to read, and those weeks after the weighing with a broken foot and a walking cast that made burning calories next to impossible I found myself skipping lunch because “I forgot” or because “the kids eat so early and I’m just not hungry when they eat” or because “I’m working and can’t really spare the time right this minute…”

Because “…”

So this last week I scheduled time to eat, and I ate. You looked on. You sneered. You shook your head. You pointed out the pooch. You laughed at my legs. You reminded me of the scale number.

But I ate.

You have been in and out of my years, whispering your untruths, pointing to your solutions that aren’t really solutions at all, luring me in.

Making me stronger.

Because, you see, every time I look you in the eye and say, “No. You cannot have me today” is another day I grow stronger. You didn’t count on this.

I don’t know how many times you will visit me in my lifetime.

I don’t know if I will ever look in a mirror and completely like—or love—what I see.

I don’t know.

But there is something I do know: You will not win.

I am stronger than I used to be when you came knocking. You don’t look quite so attractive anymore. Or fascinating. Or worthwhile.

Keep trying (I know you will), and I will keep saying no.

No.

NO.

For as long as it takes.