by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I still remember the first time you showed up at our door, three pizzas stacked in your hand, because you knew you were coming to a house of teenagers, and what teenagers don’t like pizza? Except you were coming to a house where a girl didn’t want to eat, period, because she didn’t want the pounds to show up in unexpected places and she wanted, above all, to prove herself beautiful and exceptional so she could win back the dad who had left without looking back.

You showed up and ruined that plan. I ate the obligatory piece, because it smelled so good, and then I holed up in my room, angry at my mom for bringing you home to meet us, angry that she was giving up. I knew what it meant, her bringing you home. It was the first step into a new marriage. A man had to want the kids, too, if he wanted her. The kids had to want the man, too, if she was going to marry him.

I didn’t want to agree for a time.

It took you a long time to win our hearts, because our hearts had been trampled by the one who had left, and we didn’t trust ourselves and we didn’t trust you and we didn’t trust love, mostly. We didn’t trust love to change anything. We didn’t trust love to make a difference in our already-messed-up lives. We didn’t trust love to lift us out of the pit.

We didn’t know how it would all end up. We didn’t want to get our hopes up and then be proved stupid for the hoping.

But you were brave. You didn’t let our hesitation stop you. You kept coming, those pizzas stacked in your hand and that goofy smile on your face, and you acted like maybe you liked us and maybe we could be your children and maybe this could work. Maybe.

And then Mom married you, and I sang at the wedding, and still we thought this probably wouldn’t last long, because we didn’t like you, or at least that’s what those protective walls around our hearts told us. But somewhere along the way, dislike turned to like and then like turned to love and then love turned to a father-love strong enough to walk a daughter who didn’t share blood down the aisle to her beloved.

I just want you to know that I’m so glad you stuck around. Three teenagers in the house of a single mom is a whole lot to take on, and you did it with strength and courage and the most selfless love I’ve ever known in a man, with the exception of my husband. It’s not easy stepping into that tender minefield where you will have to pick up the pieces that another man left. Thank you for taking us as your children. Thank you for showing us we were worth something.

Thank you for being our dad.

Even though we don’t share blood or name or any part of our DNA, you are a dad all the same. Sometimes our dads come to us when we’re born and sometimes they come to us later, when they find us beaten down on a gravelly path and they decide we’re worth the risk so they bend down and set us right side up, on our feet again. Thank you for deciding we were worth the risk.

There are a million reasons you could have left. The times I mouthed off, the times I didn’t listen, the time I punched you in the arm for kicking my dog away from your hunting dog, because I hated that hunting dog, and I hated you. You could have left every time, but you chose staying. You chose love.

You were at every one of my kids’ births, saying the same joke over and over so the new people there would laugh: “Yep. They look just like Poppy,” and I can’t tell you what it means to me that my kids love you so much, that they want to be with you and Mom as much as they possibly can and that they think of you only as their grandfather, not their step-grandfather. I can’t tell you what it means to see you love them like they’re yours, just like you loved us. You have adopted us all into the fold of your heart, and this is remarkable and significant and life-changing.

We have adopted you into the fold of our hearts, too. Even though you’re a step, my heart calls you dad. And today, especially, I wanted you to know that.

Thank you for being who you are, for accepting us for who we were and are, for being a little crotchety at times now that you’re getting older, for being a nitpick sometimes, for being funny and fun and mostly full of love and honor and heart. Thank you for loving us. Thank you for waiting patiently back in those early days so we could find our way into love, too.

Thank you for your light. Thank you for your son, who is like a brother to us. Thank you for the way you love our mom and the way you love us and the way you love all your grandchildren.

We love you. Happy birthday. May there be many, many more.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

This week, as we wait in expectation for the hope and light of the world, I am thinking, nearly nonstop, about a dear friend who just lost her husband to suicide. I think of her with such a profound sadness in my heart that it almost feels like a betrayal—because it is nothing compared to what she must be feeling in these days after. Walking about her home that is now empty. Remembering. Grasping for understanding. Raging. Hardening. Weeping. Hardening again.

It can feel nearly impossible to understand a thing as complex as suicide, and the world doesn’t make it easy on us, with its glib “suicide is a sin” and “suicide is a choice” and “suicide is cowardly.”

There are people who say they’ve battled depression all their lives, but they made it through by choosing joy and faith and the great big God we serve. There are people who say they have never, ever, not in the least little bit, felt like sticking a gun down their throat and pulling the trigger, even in the worst of their depressive episodes. There are people who don’t believe depression has varying degrees, sometimes keeping a person chained in bed, sometimes sending them raging out into the world, sometimes chasing them right to a ledge where tying a rope around their necks and dangling from a ceiling looks better than trying to wade through another day.

These people have never known this depression.

They have never been down so deep inside the dark that they can’t see the light that could lift them back up. They have never wondered whether the world might be a better place without their depressing self taking up unnecessary space and ruining the lives of all those around them. They have never heard the convincing lies depression can whisper.

There is no simple answer to this kind of depression.

People say that depression is a spiritual battle, a torment of faith or lack of faith, and yes, maybe it’s true. I have, after all, read the journals of Mother Teresa, full of her own walk in the dark, and I’ve read Julian of Norwich’s mystical messages on trying to find love in the deepest of sadness. They wrestled with the dark, too. But to say that the Bible or Jesus or faith and joy in a great big God are the best ways we can heal this kind of depression is to be sadly mistaken.

Depression is a disease we did not choose, and it wraps its poison around us, and it sucks all the air right out of a room and summons its most convincing lies.

This world has nothing left for you, it says.

They would be better off without you, it says.

You’ll never beat this, it says.

You are worthless, it says.

There’s a gun, it says.

You’ll feel better, it says.

Just do it, it says.

And if depression whispers those lies often enough, we start to believe them. We start to become them. We start to lose who we are, beneath all the black. And no “God works all things for good” or “We can do all things through Christ” or Come to Me all who are weary and heavy-laden” will pull us back from that ledge.

Suicide is not a choice. It’s the only thing left for those who can’t find their way back up and out and through.

I was just a girl, 14 years old, when I got off the school bus on a Tuesday. There were eight of us who got off the bus that day, and when the last footfall touched the gravel road leading to my house and two others, we heard the phantom gun shot.

It wasn’t really a gun shot. It had happened hours before, but the noise of it, the stench of it, the pain of it still hung in the air, still clung to all the trees and the weeds and even the sun that day. None of us heard it, but we all heard it.

I was in the middle of slicing cheddar chunks for my saltine cracker snack when I heard the neighbor girl screaming down the road. She was flying, or at least that’s what it looked like, her red hair whipping out behind her, feet bare on all those rocks like she couldn’t even feel them.

“Help!” she was screaming. “Help!”

My brother and sister and I came out of our house, and her cousins, who lived just beside us, came out of theirs, and we pieced together enough information so when her cousin dialed 9-1-1 we could state our emergency. Her brother, just 13, had found their dad in the backyard, the back of his head blown off by a shotgun he still held in his hands.

In the days after, the story started to make sense, but, then again, not really. He’d been on anti-depressants. He’d changed doctors. The new doctor thought he was fine without those anti-depressants, because God was enough and he could beat this with enough joy or whatever, and took him off, cold turkey. In the confusion of withdrawal and a raging depression that clamped chains around him faster than he could think, their dad pulled a trigger on the rest of his life.

Why on earth would he do a thing like that? Why would he leave four children and a wife he loved? Why would he choose to die rather than live? Those were the questions people whispered in the days after.

Even at 14, I knew we were asking the wrong questions. Because a depression like this doesn’t choose to die. A depression like this becomes the killer. This kind of depression kills a mind and a heart and a soul, and it is what pulled the trigger. There was no choice anywhere near that shotgun or his head.

I say this because I knew him, a man who loved his family more than anything else in his life. I say this because I have known more than just him. I say this because people I love have tried to jump out of moving cars on busy highways and take whole bottles of pills and slit their wrists, and some of them just didn’t cut deep enough.

Life hurts. It can wring us dry of hope and grind us into dust and blast us into bits. Sometimes we get back up. Sometimes we stay down for a really, really, really long time. Sometimes we don’t have the strength to rise again. Sometimes the dark swallows us whole. Sometimes the only way out is a way out forever.

So the real question we should be asking about this kind of depression is this: How can I make life hurt a little less for the broken ones? How can I be a conduit of hope? How can I pull someone back from the ledge or up from the ground or out of the pit?

The way we pull people back or up or out is not by misrepresenting what they’re dealing with; and it’s not by claiming we know what they feel and were just smart enough to make a different choice; and it’s not by sending them into shameful hiding with our seemingly easy answers: choose joy to be healed. Choose God to find hope. Choose life instead of death.

We pull people back or up or out by listening to their truth with compassionate understanding, giving them permission to break in our hands and stay broken for a time, heaping on them our love (without judgment) so thick and wide and warm that they can feel the hope of its relief.

This is how we walk each other home.

by Rachel Toalson | Messy Mondays, Wing Chair Musings featured

I have to get something off my chest for a minute. And it’s kind of a big something. So I’m sorry for the rant. But we live in a messy WORLD, too, not just a messy world.

You know what would be nice? It would be nice to live in a world where men didn’t get pushed up on a pedestal for “helping” take care of their children. It would be nice to live in a world where men take care of their children and it’s not considered exceptionally exceptional.

I get it. We live in a world that is still finding its way into gender equality, that is still fighting for equal rights for women in the workplace, because, go figure, some women choose to have a career outside of babies and children and home. We are still figuring all this out. Traditionally, men were the breadwinners and women the caretakers, and that meant men didn’t do such things as “taking care of the kids.” So this is a new thing for us. But I feel like maybe we should be farther along than we are.

Husband and I are very happily married. But, during prime working hours—6 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.—we split our parenting duties as if we’re single parents. Weekends and evenings we hang out together as a family, of course, but on the week days it’s one parent on six. I take the morning shift, cooking breakfast, fixing lunches, making sure kids brush their teeth and dress in appropriate clothing and get their shoes, walking them all to school, walking the three who aren’t in school back home, keeping twins out of mud and toilets, entertaining the baby, reading them stories, putting them all down for naps. Husband takes over at 12:30, while they’re sleeping. He wrestles with them and sends them outside to play and invites their friends over to play so there are twelve or thirteen kids in the house (my anxiety just went through the roof) and makes them do their homework. He knows where all the kids’ school papers go and he signs all their reading logs and he marks their behavior folders and he makes sure their lunch stuff gets put in the sink and washed for tomorrow. He feeds the baby and changes diapers and makes sure they clean up their toys before dinner so the house is somewhat tidy by the time the day is through, and then he cooks dinner.

This is not exceptional. This is called being a parent.

People are shocked that we do it this way. “Must be nice to have a husband who helps like that,” they say.

Well, I wasn’t the only one who decided to have six kids. I was not the only participant, either. Damn right he’s gonna help so I can work, too.

See, what my husband understands (and I guess this is where he’d be exceptional—because it seems there aren’t many who understand it) is that I am a better mother because of my work. Not everyone is. That’s okay. I am. He gets that, and he’s happy to make sure I get to pursue a career.

But when he’s watching the kids so I can hole up in my room and write a handful of essays that may or may not change lives, it’s not babysitting. When I go out once a month with my book club friends to talk about a book for all of five minutes and then talk about our lives for another three hours, THAT’S NOT BABYSITTING. When he decides to bake some chicken in the oven or organize some out-of-control papers or take the baby for a few hours while I get a little extra sleep, he’s not just “helping.” He’s PARENTING.

Friends and babysitters and full-time nannies help. Dads parent.

I’m glad we could set that straight.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I really wanted to walk him to school this morning because I enjoy the conversation that fresh air and exercise unwrap, but here I am, alone, sitting in our car, far away from the mess I left inside.

This morning we have bent and twisted around words like, “hate” and “can’t handle” and “hurry,” and all that time passing has not given me a boy ready for school.

All that time passing has not offered much honor this day.

I have followed him around every room, reminding him of what’s left to do, and at every turn he found distraction instead of my get-ready expectation. Those hairs he saved from the bathtub that he wants to examine under his microscope when he gets home from school today, and he just wants to make sure they’re still on the side of the bathtub where he left them. Those books in the library-turned-bedroom, where he emptied a whole shelf and only put back half last night because he got too tired to finish, and he thinks maybe now would be a good time to organize it. Those socks, unmatched, and why can’t he find socks that match with pulling every single white one from his drawer and then putting them back in, one by time-consuming one?

I bark out my commands, “Put away your blanket.” “Your pajamas. Don’t leave them on the floor, please.” “Brush your teeth now,” and I can feel the panic embracing the frustration because his distractions hide themselves in books and little brothers and stuffed animals and every random thought in his 7-year-old head, those science experiments he’d like to do (because he can’t tell me about them while he’s packing up his backpack) and those books he’d like to get around to reading (because he can’t put his pajamas in the hamper while he’s trying to compile the list in his head) and those stories he’d like to write and record in his journal.

And it’s not an honoring way to speak, this barking, and this communication, with its always nagging, always ordering, always hurrying, holds no love for another. The problem is I feel the clock, shackled to my ankle, and everywhere I follow him, it follows me, and I count down the minutes until he should be ready like it’s a death sentence.

Because it is.

Because I expect 7:15 a.m. Because here it is, and he’s not ready and it’s time to leave, now, and we must hurry, hurry, hurry.

It’s not the mismatched socks or the no-free-time-left or even the no-lunch-today-if-you-don’t-put-your-lunchbox-in-your-backpack declaration that does it, it’s the “no books today for your book box because you weren’t ready in time” that does. He collapses, liquid like the tears in his eyes, even though he knows this is the consequence, even though we’ve talked about it, even though we remind him every.single.day because this hurry happens every.single.day, and he starts throwing “punishment” around like I’ve been throwing “hurry” around, and I just cannot take one more minute because I’m sick, sick, sick of my tone and my face and my heart, none of them saying I honor you or I love you.

Hurry holds no honor.

Hurry races love, and unless we pull the reins, slow it all down, hurry will be the victor, and love will be ash-dust we trample back to the starting line.

“You have to burn to be fragrant. To scent the whole house you have to burn to the ground,” says the poet Rumi, and this is what is happening today. I am burning to the ground, and it must be the good burning, the kind of burning that turns everything toward love and honor.

Will I make it the good burning?

I walk through the fire, choking on the smoke of that old nature, stirring up the ashes lying around my feet, and my throat feels closed tight and my eyes flame with tears because I am dying, and it’s a little one who is doing it.

It’s a little one, a child, causing this self-death.

“Desperation, let me always know how to welcome you—and put in your hands the torch to burn down the house,” Rumi says, and it is desperation that is burning this house of expected perfection, this house of get-ready-in-the-time-I-give-you, this house of must-do and get-done and what’s next. Every single day it’s a war, another fire to burn my house down, because my brain is spinning round, logging that milk and the bowls of yogurt that must be cleared, quickly, from the table before curious twins go exploring and dump it all out on the living room floor, like they did last week; charting the minutes left between breakfast and leaving and all the 7-year-old must do between; registering, down in the depths, those taxes that must be filed before mid-month, just to get them off my plate.

Hurry, hurry, hurry, before it’s too late.

Desperation grips me in a head-lock, rips away those pieces that care too much what others think, that find too much identity in meeting those time deadlines, that scratch and claw and punch when expectations go unmet.

The clock, tick-tocking, and this house of self, burning. Desperation begins the fire, because there’s got to be more than this.

There is more than this.

Hurry makes it hard to see, but it’s there all the same, and once the house is burned to the ground, when those old places in me become ashes of hope, when all the smoke clears, I can see it clear.

Halfway through the day, his daddy takes up a cookie, packed in a container I forgot to put in his lunchbox this morning. In it is a note. He will pull it out and read it, maybe smiling at those little chocolate smudges on white. He will read about how a mama’s love will never run out, just like God’s, how a mama loves no matter what, how a mama can argue and argue and fight and fight with her boy and still she’ll love him just as much as she ever did before.

Because love doesn’t tally wrongs.

Because love puts up with everything and anything that comes along.

Because love endures, no matter what.

He will read about how a mama regrets the hurry and hopes tomorrow will be another try, if her boy will forgive. And in the place of that hurry house, another house builds, every time I choose honor and love over hurry, and this one will stand on brick and stone, and no fire will ever, ever, ever burn it to the ground.

Day by day, moment by moment, we build.

This is an excerpt from Family on Purpose Episode 2: We Honor God. Each Other. All People. To find out more about Family on Purpose or to sign up for the notification list so you’ll receive an email each time a new episode releases, visit the project landing page.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

The text came hard and fast and early, just before my world would explode into a frenzy of action, kids needing a walk to school, work needing doing. And though the noise did not falter, because my boys brushed teeth and scooted chairs and closed doors and opened them again and turned plates and zipped backpacks and asked what was for breakfast, my world grew silent on the heels of a monster. On the heels of death.

It is not so very long ago that my brother and his wife had to say goodbye to twin boys, on Father’s Day that year, and now here we are, in the smack dab middle of the holidays, in the sacred stretch of waiting in expectation, in the Advent season when a girl-child awaited a divine baby, and there is another baby lost.

Another baby lost. Another little girl we will not know this side of glory. This one a niece.

My sister-in-law wrote in those early morning hours, about a labor they couldn’t stop, about the pains she thought were just normal pains, because they were two days from the safe-er date, and to have it all go wrong now, to have a baby come and not be saved NOW would be too cruel, too awful, too hard to bear.

And yet she came, two days before her make-it date.

Callie Diane, a cousin and niece my boys and I prayed for every night since knowing of her tiny life inside my sister-in-law’s womb, praying without ceasing after that first text came flying across the miles almost seven weeks ago: “My water broke.” We had hoped and begged and cried and begged and whispered and begged. And the God who has the power to give and take away chose miracle after miracle, keeping this baby safe and healthy and alive for forty-one days in a womb with no water.

And then, when they were almost there, he chose to take away.

What kind of God?

///

I got the call about my beloved grandmother one morning just after feeding my toddler. Memaw had always been special to me, the rock who took us in when my mother left my father and needed a place to climb back to her feet, a generous woman who opened the doors of her home, again, the summer I finished my freshman year of college, because she knew Houston had greater job opportunities than my hometown. And she did it again the summer I graduated college and worked for the Houston Chronicle while I waited for a wedding that would bind me to San Antonio.

She’d had a stroke, my mother said. She had fallen. Something had pierced her belly and no one knew it. No one thought to check for internal bleeding before they injected blood thinners into her body. No one checked after all that, either, and she stretched out on a hospital bed and lost every ounce of blood to a wound no one could see.

She died.

And then they brought her back to life, once they’d realized their mistake, pumping massive units of blood into her, and she woke up. She lived. Except she didn’t live. Not really. She could breathe, yes. Sort of. She could see and hear and process, mostly. We didn’t really know how much of her was left. What we did know is that we were not ready to let her go. She had only lived 74 years of life, after all, not nearly enough.

I drove all that way to the hospital where she lay, and I went into the room, by myself, to see her. She was strapped to a machine that measured the rhythmic beating of her heart and the oxygen level blown from a mask and her blood pressure, which was always the problem, but not here, when medicine was injected into veins instead of forgotten in a pillbox she never opened. I looked at the tubes coming out of her, every which way, and at the mask covering half her face, and I bent over her and took her hand, and she looked right at me, and I didn’t even have to try. The words just came pouring out, words to a God who could work miracles, a God who could heal, a God who is Jehovah Rapha.

I called his name. I prayed for half an hour. I squeezed her hand. And when I was done, I asked her a question.

“You won’t give up, will you, Memaw?” I said.

And this woman who hadn’t talked since her fall, said, “No.”

“You’re going to be okay,” I said.

“Yes,” she said.

“You’re going to live,” I said.

“Yes,” she said.

They didn’t think she would talk again. There was so much brain damage, so much that couldn’t be repaired with just the giving of blood. It would have to be the giving of a brain, because this one was ruined by three minutes without oxygen and three strokes counted up over a lifetime. And yet she was talking.

It wasn’t time for her death, Jehovah Rapha said. And I believed him.

I kissed her cheek, knocking the mask a little askew, and then I fixed it, and after that I said, “I’ll be back to see you soon,” because I knew she would be up and about, defying all the doctors’ predictions, before I could make the drive to this place again. Hope walked out the door with me, warming all the places fear had chilled.

She would make it. Of course she would. Because we had prayed. Because he had answered.

And then she didn’t. She got worse and worse and worse, and it wasn’t a peaceful dying, either, it was a rough, hold on kind of dying. It was traumatic and hard and undignified, and I couldn’t believe it. I could not believe that I had been stupid enough to think that Jehovah Rapha would answer this prayer, ever.

My grandmother did not live, though we had prayed and believed.

What kind of God?

///

This morning I stood in the kitchen, listening to my boys talk about their dreams last night, and I didn’t hear a single word they were saying, because all I could think about was this baby and my brother and sister-in-law and how in the world I could tell my boys that the baby we’d prayed so earnestly for had died anyway.

And then my sister-in-law texted a picture of her perfect little girl with bruises on her face where they had tried to resuscitate her. I could not look at it without crying. Because she was perfect and because she was my niece and because she should have lived.

My boys didn’t notice, too intent on eating their breakfast, so I turned to them, and I laid it all out blunt and angry, because what did it matter about dreams when there was a brother and a woman who is a sister reeling from the death of another child?

“You know the baby we prayed for, your little cousin Aunt Sarah was carrying?” I said. They all looked at me and nodded. “She was born yesterday. And she died.”

My voice broke right in the middle of it, because who ever, ever, ever wants to say those ugly, awful, heartbreaking words about a tiny little miracle? I couldn’t say more. I could only shake my head and turn away.

And the second-oldest said, “Just like our sister,” and the table got all quiet.

They did not know their sister. But they know of her. They know of the girl we prayed for and wanted and imagined in the lineup of our family because she was made to be there. They know of the girl who died.

This pack of boys, who hear the comments people make everywhere we go, “You were trying for a girl, weren’t you?” and “All boys for you? No girls?” and “It’s too bad you didn’t get a daughter in all of those boys,” they may not understand just how cruel the taking is, but they do know that there is someone missing. Someone they might have loved. Someone who might have lived, if God had said so.

There are babies who die and babies who never come and lovers shot down in the streets and friends who take their lives and cities that are bombed bloody and fathers who fall off the wagon and grandmothers who die in a way we will never, ever forget, writhing and shaking on a bed. There are prayers answered and prayers left unheard, it seems, and we are powerless to change any of it. There is only one who holds this power.

What kind of God?

///

We didn’t expect to lose a baby. No one ever does, of course, but for us, it had always come easy, the conceiving, the carrying, the bearing. And when we learned of our fourth baby, we did not consider that it would be any different. Except it was, and suddenly I was in a place I never even knew existed, a silent place of grieving for a baby we never had the opportunity to know but who lived in our home all the same.

For three years her big brother had been praying for a sister. It’s unclear why exactly he wanted a sister, just that he was tired of welcoming brother after brother after brother. He was so excited to know that we were going to add another baby to the family, because he knew this one would be his sister. And he was right.

I took him with me to my second prenatal appointment, so he could hear the heartbeat I’d heard at the first one. And there was no heartbeat.

He sat in a corner of the doctor’s office while the nurse practitioner searched and then the obstetrician came in and searched, and he was still there, waiting to hear the rhythm, when my OB said, “These things happen sometimes” and I collapsed into a messy pile of sobs.

He was there to walk me out of the doctor’s office and he was there to try to cheer me up, though there was no cheering up from a tragedy like this one. He was there to tell his daddy,” The baby lost her heartbeat” when I could not say the words. He was only 3.

It wasn’t until later that we found out she was a daughter. It wasn’t until later that I met her in my dreams. It wasn’t until later that the silent cry slid deep into my heart, to be brought out in a great wave of rage another day, another day that was four years, five months and three days after that one. Another day that was yesterday, when another little girl died.

What kind of God?

///

They did everything they could, she said. All those doctors. All those men of science. They did EVERYTHING there was to do so they could keep a baby alive, raise her heart rhythm above 50 beats per minute, but in the end, all they could really do was place my niece in her mama’s arms and let her die. And so, in the same hospital where, 18 months ago, she watched her twin boys die, she held another baby, another promised one, another prayed-for one, and watched the breath stop in a tiny mouth and watched the color fade from a tiny face and watched the life leak from a tiny body. One pound, seven ounces, 12.5 inches of miracle, a little girl who had fought so hard to stay alive, even after she came into the world too many weeks too early.

She was blue and beautiful and alive, for only moments, and then she was forever gone.

What kind of God?

They did everything they could. It was up to God.

“My rainbow. My answered prayer. Washed away so quickly,” my sister-in-law wrote later that day.

“I’m truly sorry my body failed you, couldn’t keep you safe,” she wrote to her daughter this morning.

Three perfect babies denied them. Three babies covered in prayer and longing and hope. Three babies carried halfway, moving within, holding on to heartbeats, and then, at the very moment their parents finally get to hold them, they breathe their last breath. Given and then immediately taken.

WHAT KIND OF GOD?

I am angry. So very angry. It’s not fair. It’s not fair that it comes so easily for some and so difficult for others, this thing we call life, this thing that is really, mostly, like an every-day living war. It’s not fair that some get to have so many kids and some have so few or none at all. It’s not fair that every day my sister-in-law, a neonatal nurse, sees girls twisting in labor, girls who never wanted babies, girls who will give those babies away in the end, and she will deliver them and hold them and place them in the arms of a mother who never wanted them, and she will remember the weight of her own gone ones.

It’s just not fair.

No one ever said it would be easy, but no one said it would be this hard, either. No one said it would be this torturous, this excruciating, this traumatic. No one ever said how hard it would be to hold on to hope, because God works all things for good, and God doesn’t give us more than we can handle and through God all things are possible.

Except he doesn’t. And he does. And it’s not.

At least that’s what it feels like in a place like this one.

And of course I know the truth, deep down, because I grew up on truth, but that doesn’t change the truth of moments like these, either, when it feels like the only thing that is left for us is a tiny little god who didn’t care one bit about the tender, broken hearts of his people. Who waves his cruel little hand at tragedy and doles it out flippantly like it’s something everyone should want. Who thought it would be just the right plan to play with my brother and sister-in-law for forty-one days after her water broke, give them hope that making it this far meant they’d make it all the way this time, and then take a prayed-for, desperate-for baby two days from the we-made-it point.

What kind of God is this?

I know what kind of God he feels like right now, in times like this. But I also know that hope and faith and love are mysterious things. They hold on even in the strongest of winds, even in the deepest of waters, even in the fiercest of fires. I have been down to the bottom of the world, and I have stood back up again. I have been blasted into a pile of ash, and my dry bones have found life again.

I don’t really have the answers. Sometimes there are no answers, no matter how hard we search to find them. There are no answers to why one baby survives and another doesn’t. There are no answers to why some get everything they want and some only get asphalt and hunger and shame. There are no answers to why some die and others live.

It’s not easy to see and hear and feel God in a place as ruined as this one. It doesn’t seem like we will ever see or hear or feel him again.

But I know he is still here. I know he is peering over my shoulder, watching my every word, reading the texts I send to my beautiful sister-in-law, aiming the light so it shimmers around the corner of this dark room, still. Forging the way through and out and to the other side so it opens up like a morning glory.

So it ends its twisting, jagged path right in the lap of love. Eventually.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

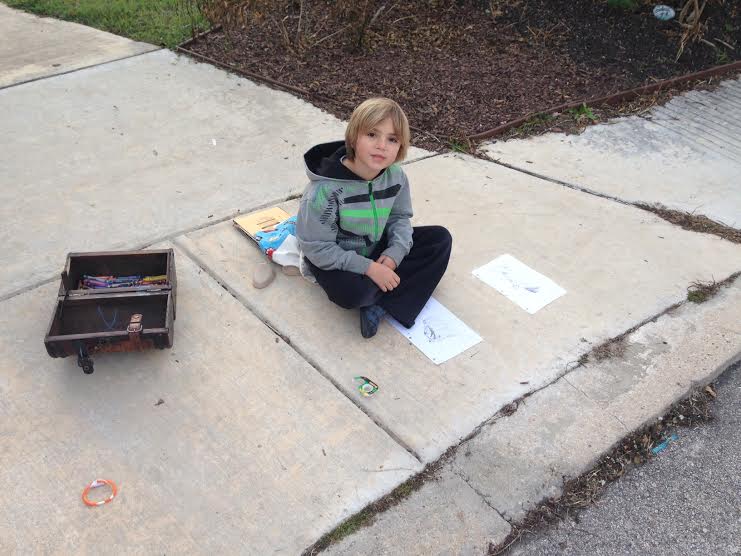

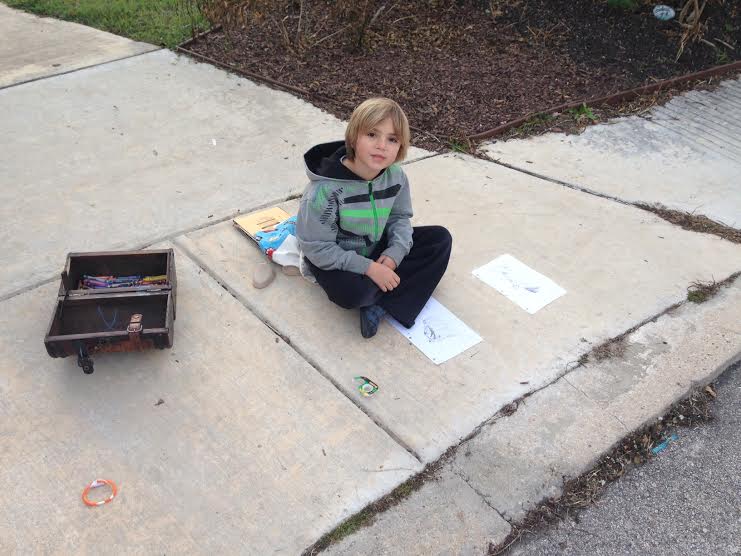

All this day we have bickered and grumbled because little boys didn’t get in the car when we said it was time to leave. Because little boys, in fact, unbuckled and wandered back into the house to pour their own glasses of milk because they just couldn’t wait for us to give them the water bottles we’d packed to bring out with us; to use the potty because they didn’t do it the first time we asked; to pack a bag of stuffed animals for him and every one of his brothers, because today is a Family Fun Day, and the stuffed animals are in our family, too.

And here we are, after a week filled with one speaking event and three band gigs and a house that bears the overwhelming craziness of it all so, instead of cleaning and catching up and making some dent on the week we left behind and the one we have ahead, we marked today as a Family Fun Day. We’re going to enjoy a day downtown in our city, visiting the Alamo and a park and some other city landmarks.

Except we almost don’t go because of all these not-following-directions-the-way-we-want-them-to children.

It’s only 10 a.m., and already their daddy and I feel exhausted. Family Fun Day, ruined by boys who want to do things their way, that’s what I’m thinking as we pull out of the driveway.

But halfway to downtown, I see it, how we have not been looking with the right eyes today.

If I look with frustration eyes, all I will see is frustration, everywhere. If I look with defeat eyes, all I will see is defeat, everywhere. If I look with expectation eyes, all I will see is failed expectation, everywhere.

Sometimes all it takes is a heart-turning to turn the whole day around.

And it’s an effort, watching a boy who wants to linger at a cool toy-airplane stand, even after we’ve told him to come on five times, and seeing not a disobedient child but a budding scientist interested in the way things work, wondering how that plane can actually fly, how he might make one just like it or better.

And it takes practice, when we’re sitting at that fountain, eating our lunch, and those boys throw rocks and leaves and whatever they can find into a wishing pond and we tell them they should stop so it doesn’t clog the whole thing up and, five minutes later, they forget our instructions, to see not children who deliberately refuse to comply but boys who have wishes to make and no coins to toss.

And it takes strength to walk all that way back to the car and tell little boys to get in and not fly off the handle when they run the sidewalk instead, strength to look on them with eyes that see little boys who had a great Family Fun Day and aren’t quite ready for it to end instead of boys who intentionally choose not to listen to parents.

Seeking wisdom and spiritual maturity and humility, here, means opening heart-eyes to see without assumption, without preconceived notions, without expectation.

How might our families change if we looked with these eyes?

How might the world change if we looked with these eyes?

This is an excerpt from Family on Purpose Episode 1: January: We embrace wisdom. Spiritual Maturity. Humility. This episode will release Dec. 2. To learn more about Family on Purpose, visit the project landing page.