by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I was halfway through my mile warmup, an easy jog down to my sons’ elementary school and back, hugging the curb of low-traffic neighborhood streets, when it slammed into the quiet morning: the honk heard round the world.

It happens occasionally. Someone will see me—a friend, the parent of my sons’ friends, someone I met recently at a school function. They’ll honk a greeting, short, friendly, if still startling enough to shoot my heart rate into sprint zone. It might not be the sort of sound that startles everyone while out running, but it definitely shakes a woman out running alone.

Maybe they don’t think about it. I can forgive them that.

This honk was different.

The driver, whose face I didn’t see (though I assume it was a man), honked for a good three seconds, maybe longer. It was a calculated honk. A mean-spirited one. A threatening one?

It would be foolish not to consider that possibility, that it was a honk meant to scare me. Or warn me. Or make me feel small and afraid.

Get out of my way, it said. Get off the street, it said. Or else, it said.

Or else what? He’d return to make sure I moved, got off the street, ran through grass and rock and all sorts of dangerous tripping hazards? He’d run me over with his big white truck’s giant tires or his black Ford F-150 with windows so tinted you can’t see inside or his blocky silver Kia Soul (sadly, this is not the first time I’ve experienced this sort of harassment from drivers; I memorize all the makes and models, commit them to memory so I know what to look out for).

Or else he’d do worse?

Who can ever tell? I am, after all, a woman running in the dark, alone.

Running alone’s not safe at the best of times, and these definitely aren’t the best of times.

For a split second, I think about chasing the offending driver to the stop sign less than a tenth of a mile away, demanding to know why he chose such a hostile gesture to express his contempt of me.

But I’m a woman, it’s dark, and no one else, for now, is around.

So instead, I spend the rest of my 7.5-mile run flinching at every passing car; watching for his return; sweeping my headlamp over every neighborhood T at each sound that could be footsteps, which could mean danger; and remembering.

It’s the remembering that burns me up inside.

I run to be free. But no matter what safety measures I take, no matter the precautions I practice, no matter where I run or when I run or what I wear while I’m doing it or the weapons I sneak into my belt, my pocket, between my fingers—

I am not free.

•

Maybe he didn’t mean anything by it.

Or maybe he meant everything I think.

When you’re a woman, you don’t have the luxury of believing the streets are safe, you are safe, a three-second (was it longer? Maybe.) honk meant nothing. It’s not fair, but there it is: every footstep, every car, every person, every noise, every strange sight, every leaf twirling on wind, caught in the peripheral vision, is a potential peril.

There are trails that run through my neighborhood. They would get me off the roads, away from cars. They’d be easier on my joints and bones, too, as I increase mileage and prepare for longer races. I wouldn’t have to deal with drivers honking, disrupting the peace of my run.

But you won’t ever find me back there, removed from civilization, as nice as the experience sounds.

That’s a line I won’t cross, because I want to make it back home.

•

Runner’s World reports that 84 percent of female runners have been harassed at least once while out running. Some of those harassments have ended in death.

We have rules: Don’t run in the dark, don’t run in isolated areas, share your route—but not with everyone, change your routes, ditch the earbuds, carry pepper spray (and whistles and weapons and phones), always stay alert to what’s around you.

I can’t get tired. I can’t drift off into my own world, let my mind wander. I can’t take a single step without keeping my guard securely in place.

It’s exhausting.

I am not free.

•

A few days ago, a friend texted: I dropped off a safety whistle, hung it on your front door.

A woman’s body was found dumped on the highway, in a construction zone, less than two miles from my house. I run a route right past the location where she was found. Rumors say sex-trafficking activity has increased in the area. A man from one of the neighborhoods I pass nearly every day has been apprehended for streaking. Multiple times.

I know you go out alone, she said. Make sure you take the whistle.

It’s another necessary thing weighing me down. Already I no longer go anywhere without my running belt, which carries my water, identification, pepper spray, and a personal alarm. I never leave the house without my phone or an easily-retrievable key in my pocket. Maybe I should get a Tigerlady self-defense claw? A stun gun? A Go Guarded Ring?

Should I brush up on my self-defense training?

Before I leave the house, I text my husband my route. If I get out on my run, feel good enough to tackle some higher hills or log more miles that day, I stick to the pre-planned route anyway, because, well, you never know.

I wear a headlamp, reflective gear, neon shirts, shoes with reflective pieces, a vest, a belt with all the above-mentioned items. How many extra ounces do I carry just so I can return home to my husband and sons, safe and sound?

•

My husband runs with two Apple earbuds, the world completely blocked out by whatever podcast or audiobook or Amazon playlist he’s listening to. I wear one Apple earbud, if any at all, because I have to be constantly, diligently aware of my surroundings—that car moving suspiciously slowly, seeming to follow me; a man on a bike about to pass…or stop?; a figure stepping unexpectedly out of the trees, right in my path.

Maybe they’re all innocent people, out for one innocent reason or another. But believing everyone’s innocent doesn’t keep a lone woman safe on a run.

My husband doesn’t even wear a headlamp in the dark.

“I don’t know how you run without a light,” I said during a recent Saturday morning recovery run, when my pace slows enough for him to join me.

“I wish you could experience it,” he said. “Feeling the ground underneath you, feeling one with nature, getting away from the lights. It’s like you can just fade into the darkness. Be, I don’t know. Free.”

Just the thought of that kind of darkness makes my skin crawl.

How many dangers wait for a woman out in the dark?

I am not free.

•

I deserve to feel safe when I run. I deserve to start and finish my runs focused on my breath, my steps, the way I feel, whatever’s on my mind, not anxious about the loud whipping wind and the dangers it might mask during the seven miles, twelve miles, twenty miles I’ll log for the day. I deserve to be free.

But that is not the world I live in. I’m reminded of that every time I text my route to my husband, every time my pepper spray thumps against my thigh, every time someone blasts a three-second honk in the middle of a still-sleeping neighborhood.

“Maybe you should stick to the treadmill,” my ten-year-old son said tonight at the dinner table.

For sixteen miles? Torture.

He nodded. “Yeah. That would be hard.” He sighed. “It’s not fair.”

It’s not, I agreed.

Maybe you should run with your husband, you might be thinking.

He runs at a slower pace than I typically do, and he doesn’t log nearly the mileage I cover. His longest run of the week is my shortest one. He prefers Camp Gladiator, high intensity interval training, strength sessions, not long meandering runs through our side of the city.

Well, maybe you should stop, then.

I won’t. I won’t let them make me.

I shouldn’t have to.

I deserve to feel safe when I run. I deserve to enjoy every minute of my chosen activity. I deserve to be free.

•

So what, then, is the solution?

I wish I could say I had a solution. But I don’t. There are no simple solutions to this problem.

But changing the conversation would be a start. Instead of asking, What can she do to protect herself better when running, ask, “What can we, as a community, do to help keep her safe when she’s out running? How can we make our streets safer for women who choose to run alone? What can I do to look out for female runners out on their own?”

Well lit streets help. Looking out for each other helps. Men being aware of the dangers women face, committing to doing their part in making sure they feel safe helps.

Beyond that? Let us run.

Let us run in the streets. Let us run in the middle of the road, if we want. Let us run on shoulders or in bike lanes or hugged up against curbs (did you know it’s safer for a woman to run on streets than on a dim-lit sidewalk flanked by trees? Attackers don’t usually venture into the middle of the street; they step out of sidewalk shadows).

Just…let us run.

•

I finished my morning’s 7.5 miles faster than I’ve ever run them before. A bright end to the less-than-bright beginning? Maybe. Maybe not.

I didn’t run alone today. But I could have done without the anger and fear that kept pace with me the whole seven laps through my neighborhood. I would rather have spent my energy on giving everything I had to that run, instead of checking over my shoulder, bracing myself for the honking driver’s return.

I run to be free.

I am not there yet.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I was an avid reader as a child. My mother would take us to our county library that was a fifteen-minute drive down two highways, and I’d stack the books as high as I could carry and take them all home and read them in less than a week. I read every Ramona book, Anne of Green Gables book, Pippi Longstocking book, every book by Madeleine L’Engle and Scott O’Dell. I was an obsessive reader; when I discovered an author I loved, I read every single book they wrote, told everybody about the author, passed books along to friends, hoping they would enjoy them as much as I did.

So many books—or authors, rather—shaped me in my formative years.

Madeleine L’Engle: I loved the science in her books, seeing a strong female character take center stage, reading the compassion and love and truth that flowed through her stories. Later, in my adult years, I would finish everything she wrote, including her adult novels and her memoir series, The Crosswicks Journals.

Scott O’Dell: The history in his books captured me, along with so many of his strong female characters (in Sing Down the Moon, Island of the Blue Dolphins, and Streams to the River, River to the Sea, among so many others). I loved reading about the culture of Native Americans, lives that were far removed from my own (though my great-great-great grandmother was Choctaw—and one day I will write about her).

The Brontës: How I loved Emily and Charlotte Brontë, the dark Gothic world of Wuthering Heights, the tragic world of the governess. Looking back on these books, the women protagonists weren’t necessarily strong, but they did everything they could in their limited circumstances during a time when women were not allowed much freedom.

Jane Austin & Virginia Woolf: I loved how they defied convention directly (Woolf) and indirectly through humor and satire (Austen). Their books still hold an important place in my heart today.

L.M. Montgomery: I loved the spirit of Anne, the way she approached life with joy and gratitude, her quirkiness, and how she defied convention in a charming, innocent way. She was brave and wild and free. I read every one of her books, with a relish I still remember.

Lois Lowry: I loved her fantastical worlds, the characters who broke free from oppressive societies, the way they found their place through struggle and their own resilience. Their journey was like a metaphor for my own life, and their victories made my own seem possible.

Toni Morrison: I still, today, read and re-read Toni Morrison, but I first discovered her in high school and read her obsessively in college. I read her for her expert use of beautiful language, the literary quality of her books, the strange threads she wove together, what she could teach me about not only the black experience or the poor experience (this latter of which I was familiar), but also the human experience.

Books told me who I could be, showed me my potential, and taught me how to write. They certainly became part of my multitude. It’s a privilege to think that maybe I can be a small part of someone else’s multitude.

What are the books that shaped you?

(Photo by Ed Robertson on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

It’s time to go!

We were on our way out the door, running late as usual, because two of them couldn’t find their shoes. One of my least favorite activities, when we’re running late anywhere, is spending time on the Shoe Search—mostly because I can’t get deeply enough into my sons’ minds to imagine where they might have left their shoes. Where would I leave my shoes if I were, say, the four-year-old? No idea (They were under a towel in his older brother’s room, along with the swim trunks we couldn’t find last night).

We finally had everyone clothed and shoed and were now ushering them out to the car. We have only recently arrived at the stage where every kid can buckle himself and my husband and I can simply slide into our seats and go, provided everyone does buckle.

But my four-year-old was taking an unusually long time to actually get into the car. He is one of the most compliant children in the bunch, doesn’t fight us on most instructions, so I reminded him it was time to get in the car, come on, we were late.

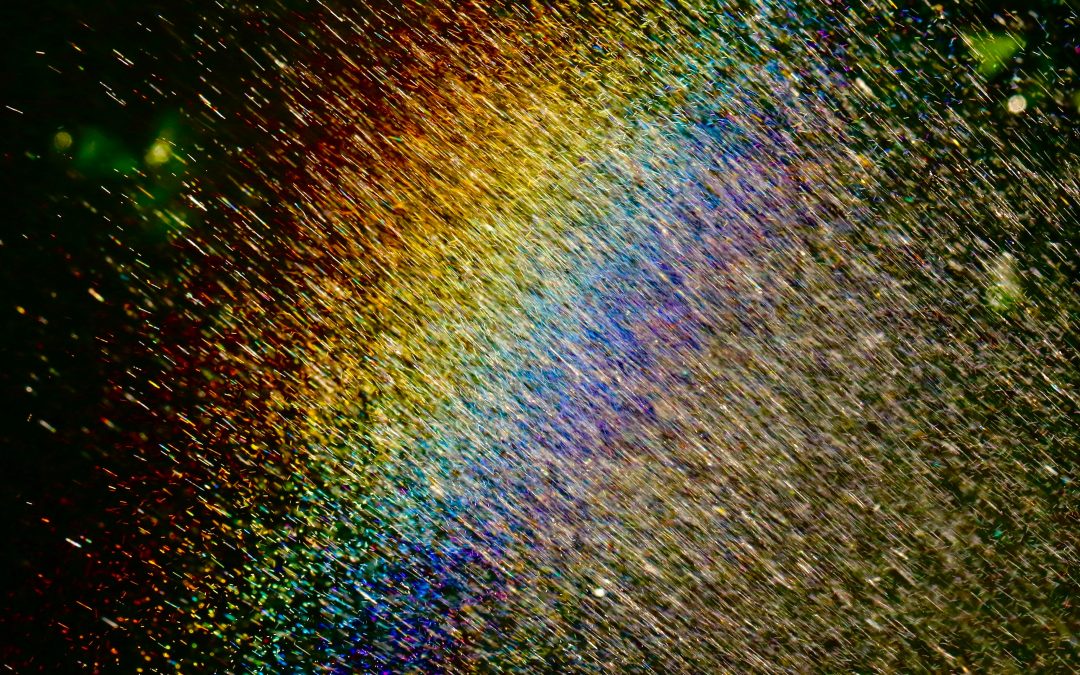

“But look, Mama.” He pointed up to the sky, and I saw it: a rainbow. Two of them, really, one arcing over the other.

Maybe I would have seen it, eventually, once we got on our way. Maybe we would have driven right into it, maybe it would have been just as bright and magnificent, maybe we would have all shared that moment with a breath and an exclamation of awe. But who is to say? Maybe I would have, instead, been staring at the clock, lamenting about how we should have left half an hour ago, I hate being late, we better not miss anything important. It’s impossible to say which track my mind would have taken.

But what really mattered, in that moment, was to stop and stare and marvel—which I’m happy to say I did.

The bottom rainbow was glowing—you could see every color as though shaded with a marker. The top one was opaque but still colorful. The air smelled musty, like rain, and I felt a drop on my hand. But it didn’t matter—I remained, staring at beauty.

So much of my life is rushing between one thing and the next—finish the laundry before heading up to work in my bedroom, washing up the dishes before beginning story time, racing out to the car to beat the clock so we can make it on time to wherever we’re going.

How much do I miss in this constantly rushing state?

Fortunately, my children move at one speed: slow. That means they often require me to move slowly as well. And rather than be annoyed by that, I want to be glad.

So I picked up my four-year-old (he won’t be picked up for much longer), and we named the colors we could see: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, pink. He laughed about how this is the same way he draws rainbows. I laughed about how he was right.

Everything else, for that moment in time, could wait.

(Photo by James Wainscoat on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I’ve started running again.

It began with a handful of miles—three or four, then quickly escalated to the six I used to run in college, when I would get up every day at five a.m. and run six miles before classes. My body remembers the routine; it’s moved back into the ridges carved out over four years of my past.

The running gives me a sense of control. There’s so much in my life that feels somewhat out of control, and it’s comforting to have that segment of time—an hour, maybe more—when I have almost complete control—over my breath, the distance I run, the speed with which I run it. I belong to myself, and my mind stills and it is only the steps, the breath, the path before me.

Running connects me fully to a moment, but it’s not only that mysterious connection that calls to me on the days I don’t schedule a run. It is the past, too.

For twelve years I have been a mother. I have given myself fully to my children. I have coaxed them through tantrums, taught them about emotions and how to read, aligned myself to their desires and needs so I can nurture and mold them into independent human beings who think and feel and decide for themselves. There is still a way to go; my oldest son is twelve, my youngest is four. They still need me, but in not quite the same way.

Two years ago, five years ago, it would have felt inconceivable to me that I would wake at five a.m. and spend an hour running six miles or more. The time to myself was short and stunted. If I had an hour to myself, I would not spend it running.

But time has widened now. There are moments when I find myself alone in my home library, when my sons are playing happily in the backyard and I can open a book and read a page or two without interruption. There are moments I realize I’ve been staring into space, daydreaming for half an hour and no one needed me. There are moments I can bookmark to run.

Maybe all this means I am losing part of myself—the part that was an ever-present, always-on-duty mother. My sons seek their father’s advice for things now, not just mine. But maybe it also means that I am gaining a part of myself, returning to a past me, remembering who I am, who I was—this person who looked forward to running six or more miles a day for the peace and quiet—the freedom—it gave her.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I’ve been feeling burned out lately. It’s a carryover from the end of the year, sliding into the new year, though I took two weeks off work to read and spend time with my kids and relax.

It’s not the work that has me so burned out; in fact, work, right now, feels like a necessary respite from the domestic world. It’s everything else—the lunches that need making, the house that needs tidying, the kids who need constant supervision.

I told my husband the other day that I almost feel like I can’t let our kids out of my sight, even though the oldest three are twelve, nine, and eight—ages at which I was already staying home alone. We live in a culture of fear—fear of what will happen to our kids if we take our eyes off them and fear of what will happen to us if other people see that we’ve taken our eyes off them. We’ve all heard the horror stories—parents (usually mothers) arrested for leaving their kid in the car for five minutes while they run into the store for some toilet paper or for letting their kid walk to or play in the park alone or for leaving them home alone while they run to the grocery store for an hour of blissful shopping. We are afraid, and so we protect from real (the repercussions of concerned citizens reporting on our perceived neglect) and imagined (child abduction, which is a percentage so low it would take leaving your kid alone for 750,000 years, according to some experts) dangers. At all hours. Every day.

Because of this, our kids don’t know how to be alone or how to care for themselves. My twelve-year-old didn’t even know how to make a pot of tea, and when, one day, he was feeling a little stuffy, he asked for some. I was busy getting breakfast on the table for his five brothers, so I told him to do it himself. He said, “But I don’t know how.”

Our kids, understandably, have trouble taking care of themselves in our overprotected world, so it’s no surprise that my most frequent burnout is parenting burnout. Mothering burnout. I feel exhausted often with what is required of me—keeping my sons out of trouble, monitoring technology time, encouraging creativity, teaching them to clean up after themselves. Making sure I don’t become a target for “concerned citizens” to call Child Protective Services.

The burnout isn’t completely caused by the protective requirement, of course. I do, after all, have six sons, and that means there are lots of needs around my house. But the break I might occasionally get from leaving my kids alone to go for a walk certainly contributes to my exhaustion.

So it was with this persistent and pervasive burnout that I began this year picking up the book, Wave, by Sonali Deraniyagala.

In this book, Deraniyagala loses her two sons—her husband and parents, too—in a tsunami while on vacation. The same things that, upon waking up, pull tight that slip of annoyance—shoes left in the middle of the floor, drawings littering the furniture in never-ending piles of paper, pleas for breakfast and complaints once it’s delivered—were things she would never experience again. She would not watch her sons navigate the explosive time of puberty, would not ever remind them to do their homework, would not break up another argument about something ridiculous.

When I finished the book, on a five-mile run on the treadmill in my garage, which doubles as my sons’ LEGO playroom, I stood there for a minute, my heart rate slowing, my breath evening, my eyes caught on the mess. What would I miss about my sons if the unthinkable happened? Everything.

I moved back into the kitchen, where my sons sat sipping smoothies, the noise at the table almost at an intolerable level. I kissed them each in turn as they swatted me away (“You’re so sweaty, Mama!) and smiled to myself, words thrumming through my head: I’m so glad they’re here.

Even the shoe I tripped over on my way upstairs couldn’t dampen the force of my gratitude and love.

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

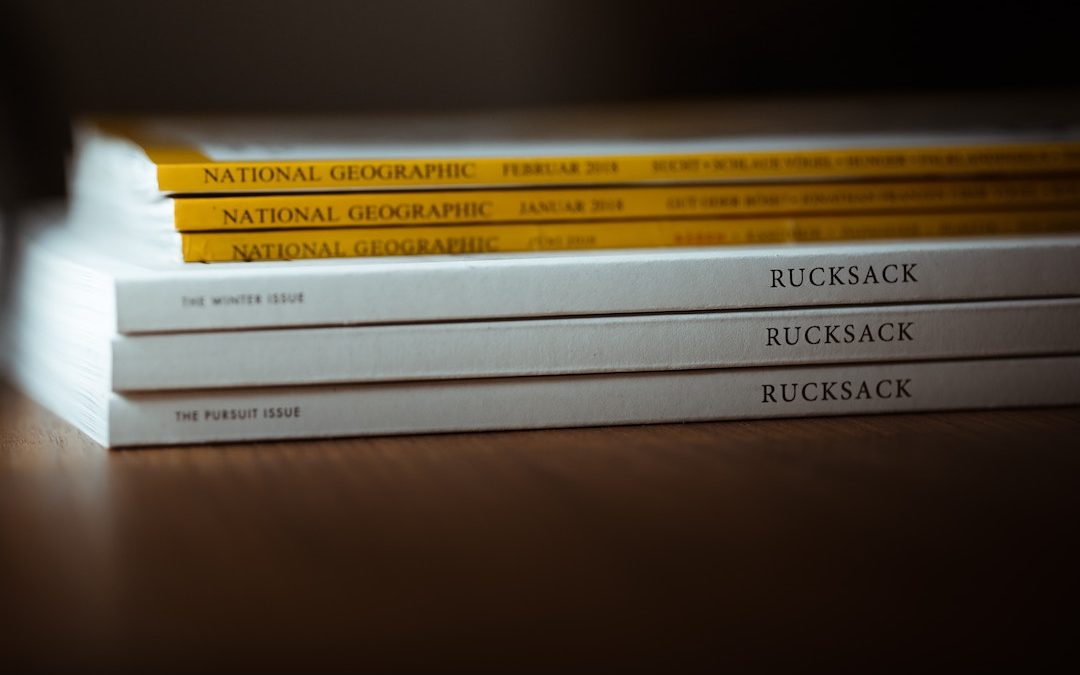

My grandmother used to save newspaper articles and clippings from Reader’s Digest (the large-print edition in later years) for the different people in her life. She’d hand me manila envelopes with cutouts paper-clipped together—about the lives of writers, the state of journalism, fitness for runners. She’d see something and investigate, or perhaps it was in the middle of reading that a family face would pop into her mind. Once she finished the piece, she would take the scissors and cut it out and store it away, until the next time she saw the person whose name she wrote on the tab in all capital letters.

I didn’t much understand this urge of hers when I was younger. The articles she passed along to me in clasped envelopes or manila folders seemed like random bits and nothing more. Sometimes they came, unexpectedly, in the mail. Sometimes she underlined things, highlighted sentences, wrote something in the margins. Most of the time she left it alone, and I had to decode what she was trying to say.

The other day I was reading a short article in National Geographic (National Geographic is to me what Reader’s Digest was to my grandmother) about a man who climbed a mountain without a rope. Free climbing is what they call it. While that part was interesting enough, it wasn’t what made me think of my husband. What made me think of my husband was the fact that someone filmed a documentary about this man’s climb.

My husband is a documentary filmmaker. The article included information about the equipment used for the filming (which my husband will often talk about, though I can’t usually follow), how he safely filmed the climb, and the number of hours required for preparation alone.

I dog-eared the page, thinking my husband would enjoy the article.

Later that night, when all the kids were finally in bed, I mentioned the article to my husband. He seemed lukewarm about it, much like I was back when my grandmother would hand me articles she’d saved for me. I handed it to him anyway, said, “I really think you’d enjoy it.” He set the magazine on his bedside table. It’ll take him months to read it—or maybe he’ll read it tomorrow.

Either way, I could imagine my grandmother, who’s been dead ten years, smiling, saying, “You see?”

And I do.