by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I was walking my sons to school the other day when the woman crossing them said, “I looked up your book yesterday.”

I never know what to say in situations like these, so I just said, “Oh, yeah?”

She said, “Yeah.” She didn’t say anything else about my book (I can’t say I wasn’t glad). She moved on to tell me that she’s been urging her husband to write a book for a while. She said, “I think he would write it well, but he just doesn’t have the time.”

I can empathize with this completely. My first traditionally published book was written in short bursts—half an hour here, fifteen minutes there. Time—or the lack thereof—is one of the largest reasons more people don’t write.

But having found the time, I know, too, that there is another, larger reason that more people don’t ever finish their book, and it’s this: writing demands much of authors.

That “much” includes, of course, time, but even more than that it includes everything a writer gives. What I mean by that is both simple and complicated: a writer gives herself.

There is not a book I have written yet that does not contain large pieces of me. I split open my heart and my soul and my brain and meet the page in the most vulnerable place, disrobing family secrets (even if they are hidden behind fiction or metaphor), examining the darkest places of my mind, telling stories I might rather forget. There are projects that have nearly broken me—a current one is a memoir I’m working on about the first summer I went to see my dad and his new family after my parents divorced. It took me three years to write down a fictional story about a suicidal teenager because within the story are pieces of myself, my teenage years with my brother, and a current ongoing struggle with my pre-teen son. I cried through the final draft of a picture book that just went out on submission—because it contains so much raw, unbridled pain and extravagant hope.

Writing a book is not as simple as choosing an idea, doing research, carving out the time to put words on a page. Writers give themselves, too.

This is partially why, when an author’s book is finally released to the world, there is so much elation mixed up with fear and unease. We are known more fully by our work. And we know that not everyone will be kind to those pieces of us out in the world, threading into our stories or essays or poems. We hope they will be, but we don’t live in an ideal world, and the words of others sometimes sting in our most vulnerable places.

Before I get started on a new project, I always take a deep breath, close my eyes, and repeat to myself these words from Maya Angelou:

“My wish is that you continue. Continue to be who you are, to astonish a mean world with your acts of kindness.”

Though I know it will be difficult to peel off those scabs that have grown over verbal abuse and use the old wounds to tell a story about the pain and confusion of a boy, I know I must—because other children live in a situation exactly like that, and they need to know they are worthy of acceptance and a future and the greatest of love. I enter into the ache, I let it blast through my chest, and I give all of myself to the storytelling, to the examination of difficult things, to the redemption of what has been broken. Tikkun olam.

I give because I love my readers. I give because I desire to see a world in which every person realizes their worth and significance. I give because it is my purpose, because it is the way in which I meet people and leave a part of myself with them. Because I take seriously the words of Fred Rogers: “If you could only sense how important you are to the lives of those you meet; how important you can be to the people you may never even dream of. There is something of yourself that you leave at every meeting with another person.”

I hope I never hold back.

Next time you pick up a book, remember: authors don’t merely give time and money and hope and creativity to the project in your hands. They give, too, themselves.

(Photo by Ewan Robertson on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

We are talking of the future and business plans and all these topics that beckon anxiety from its hiding place, because we’re in such a precarious position with so many unknowns. He is asking for hope and trust and certainty, and I can’t give it in light of all those years when plans didn’t work out like we thought they would and disappointment came loping in like a stray dog. What if this new plan ends the same way all the others did?

His eyes, wild and furious, tell me I’ve said exactly the wrong words at exactly the wrong time in exactly the wrong way.

But there are children in the car, so he bites his lip and stares out the front window, and he will not be able to say what he wants to say until we get home and feed kids and put them down for their naps, because there is not a moment alone until we do.

We let the silence speak for us.

My head starts turning it over and over, how maybe I shouldn’t have said what I did, but, God, I’m so tired of arguing about the same old things and having the same old conversations about the same old dilemma. All those years adding up to tired brought words to my mouth without so much as a second thought. That’s not an excuse. Simply a reality. A confession, maybe.

You can’t take back words. So these words sit and fester in both our hearts, waiting for boys to sleep so we can fight the ugly wrinkles back into smooth.

///

It took him a while to convince me to spend the rest of my life with him. There were two other possibilities, a boy destined for politics and another for professional baseball, when he came along. My future husband came crashing through both their plans with his black curls and blue eyes and a voice that could soothe me into love when he talked, but especially when he sang.

The problem wasn’t that he was the tiniest bit dorky or that he wasn’t very good with money or that he wasn’t even sure what he wanted to be when he grew up. The problem was mostly that when he looked at me, he really looked at me. He really saw. He really knew in the deepest ways a person could know. It unsettled me. I was so good at hiding feelings and pretending that life’s hard punches hadn’t even winded me and constructing this identity of a laid-back girl who had her whole life figured out. I worked so hard to lock away those secret places. And here was a boy-man dismantling all the walls and staring into the bare places and shouting that what he saw—all the ugliness curled inside a little girl’s heart—was actually beautiful.

I wasn’t ready for that, and I wasn’t sure he was The One, and I couldn’t really tell if this was love or a timid kind of hope.

Mostly, though, I was afraid of the greatness he saw in me.

I held him at arms’ length for as long as I could, and then I crumbled. He slipped a ring on my finger, and we stepped into forever.

///

He still knows in the deepest ways a person can know. When I say there’s nothing wrong in that specific tone of voice, he knows it means there really is; I’m just not ready to talk about it yet. When I say I had a hard time writing today, he knows it’s because it’s the last day of the month and tomorrow I’ll have to sit in front of a computer and try to reconcile our budget. When I say I need to go to Wednesday night church, he knows it’s because I need time to myself, without anyone bothering me or trying to get my attention or asking me for something. He just knows.

He knows how I’ll respond or react before I do. He knows what I’m feeling before I can even articulate the words. He knows my motivations and my fears and my shaky hope and my annoying realism and the way I tie my shoes with two bunny ears and how I’ll feel about my son’s playground experience today and the words I’ll say about the one who won’t leave us alone at bedtime and what I think about the book I’ll pull open tonight.

Living together, scraping against each other’s edges, sharpening the iron strength of another for as long as we have, means that you really, really know someone in the deepest places. You know how they’re feeling and how they see the world today and what they need at just the right times. It can feel scary to be known this way. When we are known, we have no place to hide. When we are known, we are vulnerable.

When we know, we see all their vulnerable. This knowing can turn cruel, and sometimes it does, taking its anger-shot at the exact place it will hurt the most.

That’s all a part of the marriage story.

///

I had never met anyone quite like him before. When I was sick, he stayed by my side, holding my hair as I bent over the toilet or lying beside me while I burned up with fever or carrying me down fifteen stairs after I broke my foot.

When I spoke, he listened and heard. When I dreamed, he believed those dreams were possible. When I cried, he did not run away. When I raged, he met the fire.

For the early years of our marriage, I lived with a ball of black in my heart. It spoke of abandonment and fear and a bottomless well of insecurity. Sometimes that ball flew out of my mouth and wrapped around words. Sometimes it took off the screen door of my heart and nailed up a cedar one instead. Sometimes it aimed its arrow and sent hurt into my husband’s heart.

Every single time he forgave. He never held grudges or threatened leaving or wondered if he might do better for himself somewhere else. Instead, he stood solid against all those years until I began to soften. And then he loved me more tenderly, more profoundly, more wholly.

I have still never met anyone quite like him.

///

A fight like this one is not the first in the nearly twelve years we’ve been married. Of course it isn’t. Because we’re human. We’re imperfect. We’re selfish. We speak without thinking. And when you’ve been married this long, you know what all the words say, but you also learn what the silences between the words say.

In every marriage there come seasons of waking up on a different page in a different book, feeling more like strangers who fight than friends who talk. We have had days, weeks, months of tension and push-and-pull and butting heads and asking forgiveness, and every single time—every single time—we have walked out of that shaky season stronger than we walked in.

Every single time.

We fought and we disliked and we raged and we cried and we opened our umbrellas and we hid in ditches during the storms that sometimes only dumped rain but sometimes felt like a Category 5 tornado, and through it all we fought for love.

We all say words we don’t mean to the ones we love. And then we all have the privilege of stepping outside ourselves and meeting the other person’s hurt with humility and remorse.

The secret to saving a marriage is not avoiding all the conflicts. The secret is letting go of our pride. Saying we’re sorry. Choosing love over winning. Forgiving.

Sometimes, when we are entrenched in those days and weeks and months of conflict, when it feels like we can get nothing right and we can’t say a word without arguing, it can feel like conflict tells the whole story of our marriage. But if we look closely enough, we’ll see.

Forgiveness after forgiveness, this is the whole story of a marriage.

And so, today, while boys eat their lunch, I follow my husband up the stairs and I wrap my arms around him and speak my apology into his ear. Tears mix on both our cheeks, but that salty water is really sweet. So sweet.

Because it tells the real story of a marriage. The real story of partnership. The real story of love.

This is an excerpt from We Count it All Joy, a book of essays. For more of Rachel’s writings, visit her Reader Library page, where you can get a couple of books for free.

(Photo by Zoriana Stakhniv on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

At the close of every year, I always find myself turning my gaze to the new year—sometimes even before it’s time.

There are certainly times in which to begin anew—the beginning of a summer, a birthday, an anniversary, the start of a school year. But there is no time that lends itself to new beginnings quite like a new year. It’s a wide open opportunity that meets each of us with a clean slate, a schedule that hasn’t yet filled with activities (unless you have school children). We aren’t on the hook for projects to deliver or goals we’ve set and still need to meet. Everything is expansive and rich with potential.

If you want to make a drastic change in direction, a new year is the perfect time to do it.

Sometimes that can be an unsettling thing, like a writer facing a blank page for the first time, which is pretty much any time, because there is no formula for writing. So much space and possibility can feel intimidating to some.

I get giddy with anticipation. I evaluate and schedule and write down goals and revise goals and decide on publication dates for self-published books and mark dates for traditionally published books and plan for the projects on which I’d like to focus for the coming year and try to anticipate the bumps I might meet in the road (though I can’t always predict those with any accuracy.). I analyze daily writing expectations, manage those expectations, strip everything away and add it back. I brainstorm new ideas and white board and think, think, think. I evaluate my schedule and see if it still works for me.

People who know me well know that I also, at the end of every year, choose a word with which to frame my new year—in both family and in business. Our family word for 2019 is “optimize”: we’ll be looking at processes and rules around our house and reevaluating and streamlining them. We’ll be working, mostly, on relationships and optimizing the time we have together.

I had trouble settling on a word to frame my business. But after much thought and consideration, I chose the word “assert.”

Assertion is not one of my strengths. When faced with a decision to assert my needs that come in conflict with another’s needs, I will generally default to that person’s needs. This could be the result of residual trauma from my past, or it could simply be a weakness of mine cultivated in my childhood quest to demand the least attention, step on the fewest toes, be the “easiest” child. But what I have learned of weakness is that when we recognize it, examine it, and intentionally practice strengthening it, it will not remain a weakness for long.

This last year I encountered several instances in which I needed to assert myself in order to make sure my needs were met in a timely and efficient manner. Instead, I chose the least resistant path—that of acquiescence and accommodation.

Assertion is an important part of communication when you work for yourself and you depend on other people for your ultimate success. Asking for what you want and need is necessary for healthy relationships, successful careers, and even enduring marriages.

I don’t yet know for what I will ask in this new year, at least not completely. But I do know that when I stumble into a situation that calls for assertion, I will be (mostly) ready to stumble through it (we all start somewhere) and, by the end of the year, walk through it with my head held high.

What word will you choose to frame your year?

(Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I sat in my bed, reading. My eight-year-old appeared by the side of the bed and said, “The speech teacher took me out of class today. She said I say my s sound wrong.”

I know this already; I’ve been in communication with his teacher about it. I said, “Oh yeah? How did it go?”

“She taught me how to do it right. But I forgot.” He danced out of the room, as though the conversation was now done. I watched the doorway for a minute, thinking maybe he’d gone to get something.

A few minutes later, when I’d returned to my book, he crept back inside my room. “I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to say my s right,” he said. Before I could answer, he shot from the room again, this time racing his words out.

It didn’t take him long to return. He said, “It’s something like this.” He tried to say an s. He tried again. And again. His eyes filled. “I can’t do it.”

I took him in my arms and told him that just because he couldn’t say the s sound correctly doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with him. I don’t always know the right thing to say at times like these, but I do know that kids need reminding—often—that there is nothing wrong with them, they are brilliantly spectacular as is, they are loved. I always start there.

He pulled away and said, “What if I don’t ever say them right?” He looked at the ground, not at me.

This son is my pessimist. He will try and try and try until he is weary from trying, but he will rarely believe, even in the trying, that anything good will come of it. When he loses something, it will surely be gone forever (but he’ll still keep looking). When a friend isn’t home to play with him for a day, he’ll probably never be able to play with this friend again (but he’ll still knock on the door and ask tomorrow). When he has to clean up his mess before tech time, he’ll probably never, ever, ever be done (but it’ll only take him a minute).

I could feel his anxiety, hanging like a heavy cloud between us.

I said, “How old are you?”

“Eight.”

“For eight years you’ve been saying the s sound wrong. It will take more than one session with the speech teacher to correct your habit.” I paused to make sure he was still listening. He was playing with something on my bed, his head tilted a little. I knew his ears were tuned to me. I said, “You’ll get it. I believe in you.”

Sometimes a parent believing is enough.

I’ve had to reassure him of this same thing several times over the last weeks. There’s nothing wrong with you, remember who you are, you’ll get it. With enough repetition, the words will get lodged so deeply in him that he’ll never get them out.

In the middle of all that repeating, all that reminding, we continue to help him practice his s sound, perfect it, have a little fun with it. And maybe, by the end of all this, when the s sound comes easily and naturally as though it were never a problem in the first place, he’ll realize that nothing is impossible when you have a team.

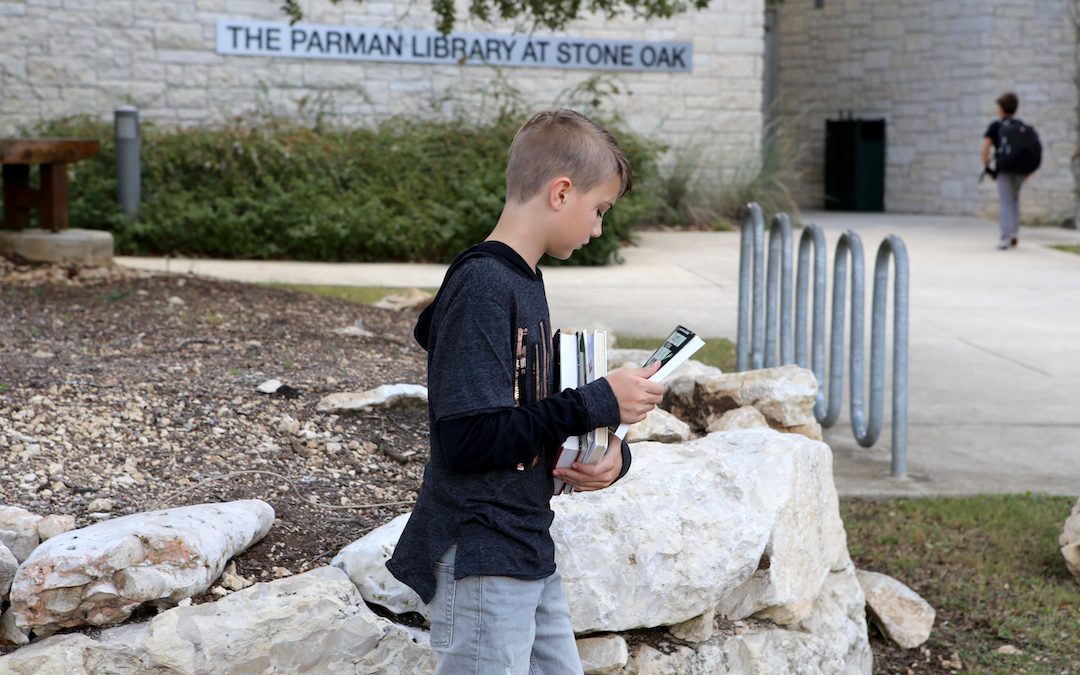

(Photo by This is Now Photography)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

“Can I show you this real quick?”

My oldest son held out the old phone we gave him for his creative projects and a bit of technology time for which he has to complete a number of things before it’s earned. I was putting the last touches on dinner—some baked chicken, some roasted beets and zucchini, and slices of watermelon for dessert. I was moments away from calling in the rest of my sons, from hearing them all complain about how gross dinner looks, from sitting down and trying to remain present.

I’d had a lot on my mind lately. My first traditionally published book had just gone to press, I was waiting to hear back about a potential deal on a second one, and a third manuscript was not quite there yet, giving me fits and starts, making me wonder if it might not just be easier to give up on it.

This summer has felt like a constant battle to remain present.

So I watched the video, impressed by how meticulously my son arranged his LEGO mini figures and took their pictures and set the scene for a story.

“You put a lot of work into that,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said.

“How long did it take you?”

“An hour.”

An hour for five seconds of captured video. He is more patient that I’d ever known him to be. And, like it always does when faced with a moment of brilliance from my children, my heart looked up, straightened from its wilting posture, squared its shoulders, and said, Life is grand, isn’t it?

Until it was time to do after-dinner chores and the same son who spent an hour arranging tiny LEGO pieces and taking pictures could not be bothered to spend fifteen minutes rinsing and stacking dishes into the dishwasher.

The things we love are much easier to spend time doing than the things we loathe.

(Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash)

by Rachel Toalson | Wing Chair Musings

I could feel it coming: the nervous anticipation of the first day of school.

When I was a kid, I threw my nervous energy into choosing my first-day-of-school outfit (which got progressively more complicated as I grew older and cared more about first impressions). I would lay out my clothes, visualize the next morning, plan for the unexpected.

My sons are not so conscientious. I am the one who usually lays out their first day of school outfit, not because they can’t but because for now they humor me with a special coordinated outfit (which is not the same as matching, by the way; in their coordinated outfits I try to choose pieces that account for their color and style preferences and their personalities, within reason. No, the 8-year-old cannot wear a fluorescent orange Pokémon shirt the first day of school.) Once I’ve released the outfit, which I keep in my closet for security purposes until the night before the first day, they will stare at their shoes, drape socks over the sides, run their hands across their new backpacks, presumably thinking about what the next day will hold—or perhaps thinking nothing at all.

This year we had a brand new experience for the first day of school: my oldest son was entering middle school. So the nervous energy that accompanies all first days of school held something else: a tinge of fear.

He hovered outside our bedroom, meandering in every so often so we could tell him, gently, that he needed to get to bed so he would be well rested. He lingered. He paged through books on my bedside table. He examined his fingernails.

I could tell he wasn’t quite ready to close the door on summer. He knew—he knows—that life from here on out will be much different.

Growing up isn’t always easy. I daily watch my sons pull against the tether that keeps them dependent on me, ever ready to assert their own independence, even if they’re not quite capable yet. And then a new stage of life presents itself, and freedom widens, and they huddle at the precipice, peering over the edge, questioning whether they are actually ready. They wonder if they have what it takes to fly. They assess how hard the ground might be, because their safety net isn’t quite as thick as it used to be (though this is just an illusion; they always have a thick safety net).

At some point, I drew my son nearer to me. I held his hand. I did not tell him he would be fine, school would be fun, everything would be easier than he thinks; none of that is assured. I only said, Remember who you are.

He knows what this means. Since our kids were young, any time we drop them off somewhere we will not be, we have told them, Remember who you are: strong, kind, courageous, and mostly son. It’s a phrase they have heard all their lives. It’s a phrase that speaks of love—that they will always, no matter what, be loved.

An easy, fun, even good year is not assured my son; that’s not how life works. But what is assured is that at the end of this next season of life, he will have grown, learned, and walked deeper into who he is. And no matter what kinds of twists and turns this year holds, no matter where he goes or what mistakes he makes or victories he has, he will never be anything other than who he is: strong, kind, courageous, son.

Worthy.

Half an hour past his bedtime, he finally found his way back to his room, filled his diffuser with essential oil, and read until he fell asleep, covers pulled up to his chin, book marked with a finger.

The same kid—but different.

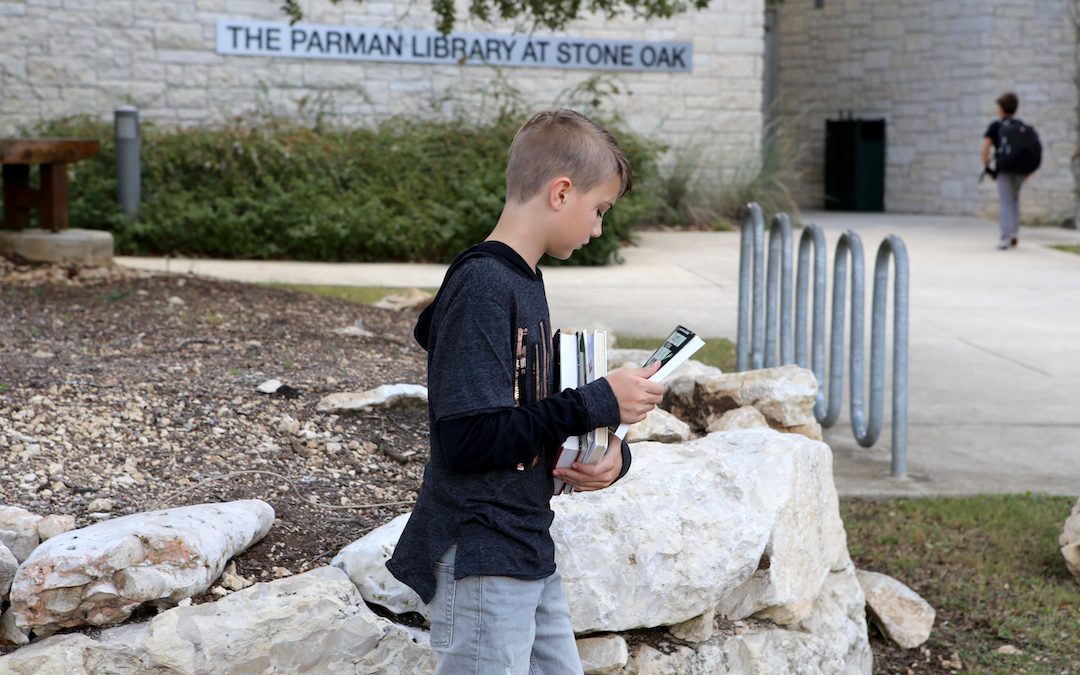

(Photo by Helen Montoya Henrichs.)