My grandmother used to save newspaper articles and clippings from Reader’s Digest (the large-print edition in later years) for the different people in her life. She’d hand me manila envelopes with cutouts paper-clipped together—about the lives of writers, the state of journalism, fitness for runners. She’d see something and investigate, or perhaps it was in the middle of reading that a family face would pop into her mind. Once she finished the piece, she would take the scissors and cut it out and store it away, until the next time she saw the person whose name she wrote on the tab in all capital letters.

I didn’t much understand this urge of hers when I was younger. The articles she passed along to me in clasped envelopes or manila folders seemed like random bits and nothing more. Sometimes they came, unexpectedly, in the mail. Sometimes she underlined things, highlighted sentences, wrote something in the margins. Most of the time she left it alone, and I had to decode what she was trying to say.

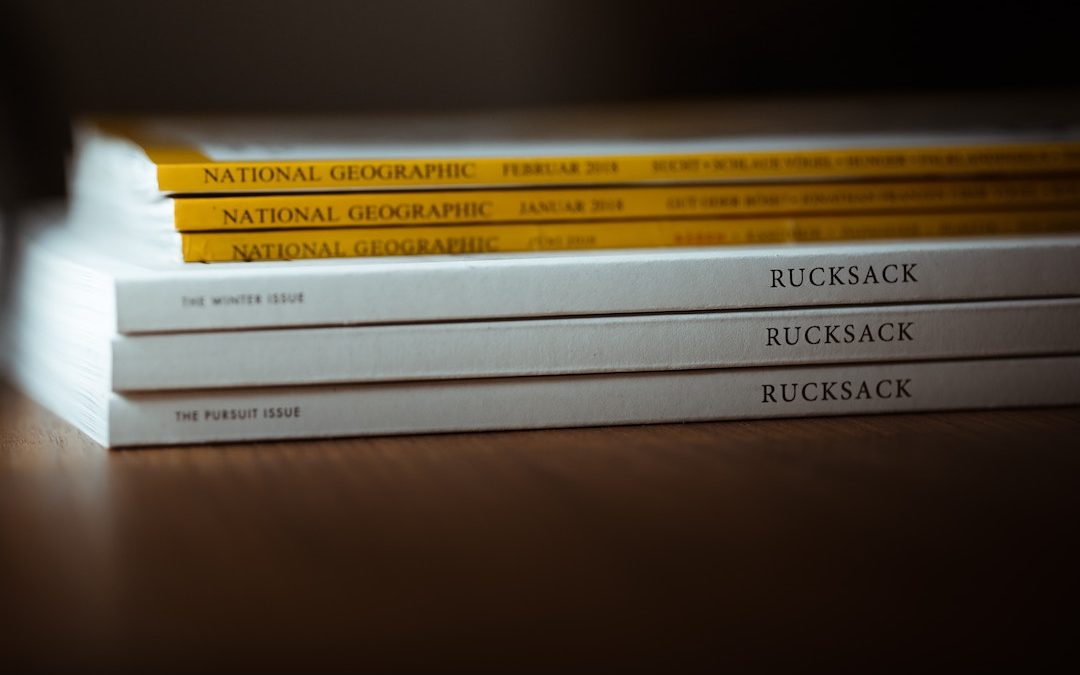

The other day I was reading a short article in National Geographic (National Geographic is to me what Reader’s Digest was to my grandmother) about a man who climbed a mountain without a rope. Free climbing is what they call it. While that part was interesting enough, it wasn’t what made me think of my husband. What made me think of my husband was the fact that someone filmed a documentary about this man’s climb.

My husband is a documentary filmmaker. The article included information about the equipment used for the filming (which my husband will often talk about, though I can’t usually follow), how he safely filmed the climb, and the number of hours required for preparation alone.

I dog-eared the page, thinking my husband would enjoy the article.

Later that night, when all the kids were finally in bed, I mentioned the article to my husband. He seemed lukewarm about it, much like I was back when my grandmother would hand me articles she’d saved for me. I handed it to him anyway, said, “I really think you’d enjoy it.” He set the magazine on his bedside table. It’ll take him months to read it—or maybe he’ll read it tomorrow.

Either way, I could imagine my grandmother, who’s been dead ten years, smiling, saying, “You see?”

And I do.