I’ve mentioned before that when I find an author I like, I will read everything in the world they have to offer. One of those authors is Rainbow Rowell.

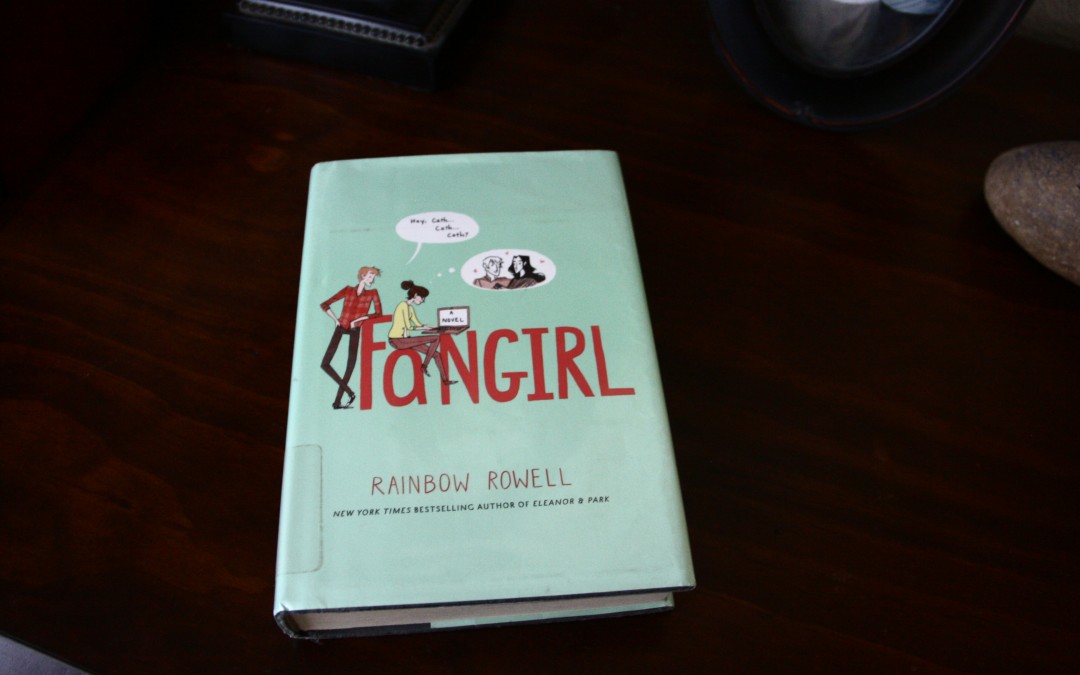

I found Rowell through Eleanor & Park, which I read after a friend of mine told me it was one of her favorite young adult reads. I’m not a big young adult reader, but I thought I’d give it a try. It was so exceptionally written, so exceptionally true, so exceptionally part of the high school experience I remember that I had to see what else Rowell had up her sleeve. So I embarked on Fangirl.

Fangirl takes place at a different time and in a different era in a young adult’s life: college. It follows the story of twin sisters, Cath and Wren, who are learning to navigate the choppy waters of college. Wren wants to be on her own, build an identity outside of her identical twin sister, and, for the first time in their lives, Cath does not share a room with her sister. Cath is much more bothered by this than is Wren, who was always better at making friends. So Cath hides herself away in her fan fiction, which she writes for a large following. Wren, meanwhile, hides herself away with partying and alcohol.

During the story, the two sisters struggle with their relationships and their own identities. One of the best aspects of the book was all the issues it explored—alcoholism, the forgiveness of an absent mother, caring for a mentally ill father. It was an important contribution for the world of young adult literature.

One of the strengths of Rowell’s writing is her grasp on characters. In her stories, the characters fly off the page and into the reader’s life. They are real people with real problems and real struggles. They are some of the most believable characters I’ve ever read. Rowell has great insight into the human condition and also the life of a young adult, which is probably why her books are so popular.

Take this scene between Cath and her father:

“He was wearing gray dress pants and a light blue shirt, untucked. His tie, orange with white starbursts, was stuffed into and hanging out of his pocket. Presentation clothes, Cath thought.

“She checked his eyes out of habit. They were tired and shining, but clear.

“Cath felt overwhelmed then, all of a sudden, and even though this wasn’t her show, she leaned forward and hugged him, pressing her face into his stale shirt until she could hear his heart beating. His arm came up, warm, around her. ‘Okay,’ he said roughly. Cath felt Wren take her hand. ‘Okay,’ their dad said again. ‘We’re okay now.’”

It is clear that Cath’s father loves her, but it is also clear that Cath loves her father. Cath and Wren’s mother left when the girls were very young, and it’s only been the three of them for as long as they can remember, and this scene is a perfect mirror into that internal life. One gets the impression that their father has told his daughters those words all their life: “Okay. We’re okay now.” It’s a scene fraught with emotion and unspoken remembrance, one that, somehow, speaks of universal experience.

Rowell also has a practiced hand at dialogue, which is probably the result of her knowing her characters so well.

Here’s another great characterization passage, shown mostly through the description of a character:

“Reagan was looking at Nick like she was already tying him to the railroad tracks.

“Wren was looking at him like she was one of the cool girls in his stories. Oozing contempt.

“Levi was smiling. Like he’d smiled at those drunk guys at Muggsy’s. Before he’d talked Jandro into throwing a punch.”

Each unique description shows so much personality. It’s clear that Rowell knows her characters and exactly how they would react to the same situation.

Rowell also has a way of sneaking truth into her passages. Every writer will understand this passage between Cath and her creative writing professor:

“‘But Cath—most writers don’t. Most of us aren’t Gemma T. Leslie.’ She waved a hand around the office. “We write about the worlds we already know. I’ve written four books, and they all take place within a hundred and twenty miles of my hometown. Most of them are about things that happened in my real life.’

“’But you write historical novels—’

“The professor nodded. ‘I take something that happened to me in 1983, and I make it happen to somebody else in 1943. I pick my life apart that way, try to understand it better by writing straight through it.’

“‘So everything in your books is true?’

“The professor tilted her head and hummed. “Mmmm…yes. And no. Everything starts with a little truth, then I spin my webs around it—sometimes I spin completely away from it. But the point is, I don’t start with nothing.’”

Because Cath was a budding writer, Rowell inserts some passages about writing.

“This wasn’t good, but it was something. Cath could always change it later. That was the beauty in stacking up words—they got cheaper, the more you had of them. It would feel good to come back and cut this when she’d worked her way into something better.”

“Sometimes writing is running downhill, your finger jerking behind you on the keyboard the way your legs do when they can’t quite keep up with gravity.”

Rowell also utilizes great descriptions to write her deep scenes and give her readers a look into the lives of the characters. Here is a description of Cath’s room, when a boy is seeing it for the first time:

“It looked like a kid’s room now that she was imagining it through his eyes. It was big, a half story, with a slanted roof, deep-pink carpet, and two matching, cream-colored canopy beds.”

It’s almost as if Rowell walked into the room and looked around and then described it from memory. She is fantastic at setting scenes like this, pulling a reader in as if they are the ones merely observing.

“Cath put on brown cable-knit leggings and a plaid shirtdress that she’d taken from Wren’s dorm room plus knit wristlet thingies that made her think of gauntlets, like she was some sort of knight in pink, crocheted arms. Levi’s teasing her about her sweater predilection had just made it more extreme.”

I love this passage because of the way it pulls us into the time period when Cath is experiencing her college days. Rowell uses the fashion of the day to pulls us into the scene.

Rowell is also a master at providing filler information.

“Wren lifted her head and wiped her eyes with the back of her thumbs.”

One could imagine Wren doing exactly that.

And, of course, there’s enough romance in the book to make your knees all weak and your stomach fluttery. You care about the characters so much you’re just glad that they’ve found something as elusive as love.

“He called to tell her he was back. Knowing they were in the same city again made the missing him flare up inside her. In her stomach. Why were people always going on and on about the heart? Almost everything Levi happened in Cath’s stomach.”

If one has ever felt the stirrings of desire, one knows it doesn’t happen in the heart at all. It happens much deeper, and so we can empathize with Wren and her developing love.

Other passages deftly communicated the tone of the romance between Cath and Levi, the way new love is all senses, all poetry, all exciting and beautiful and scary and, mostly, wonderful.

“His heart beat in the palm of Cath’s hand, right there, like her fingers could close around it…”

“Love was all soft motion and breath, curves and warm hollows. Levi’s chest was a living thing.”

Cath thinks in metaphor and poetry:

“Cath was pretty sure that Levi actually was the brightest thing in the room, in any room. Bright and warm and crackling—he was a human campfire.”

“She didn’t have words for what Levi was. He was a cave painting. He was The Red Balloon.”

Rowell’s stories are not just good stories—they are instructional texts, showing writers how to create believable characters, how to write deep scenes, how to talk about romance and new love in a way that will inspire love in the hearts of readers.

Much like Eleanor & Park, Fangirl is a fantastic contribution to the young adult world, examining not only tough issues but also, subtly, showing what it means to really love.