For the past year, I’ve been studying the art of humor writing, because I run a parenting humor blog, and I didn’t want it to be just run of the mill. There are so many humor writers who make their living from what I call roasting—making fun of people who are in the same camp they are, and I’ve found that it rubs me the wrong way.

So when I discovered the classic humor of Erma Bombeck, who was a humor writer in the 1960s (and on) published in a syndicated newspaper column, I knew I needed to channel HER. She wrote about suburban home life and described it so hilariously—without throwing her peers under the bus—that I was instantly drawn to her. I’ve now read five of her books.

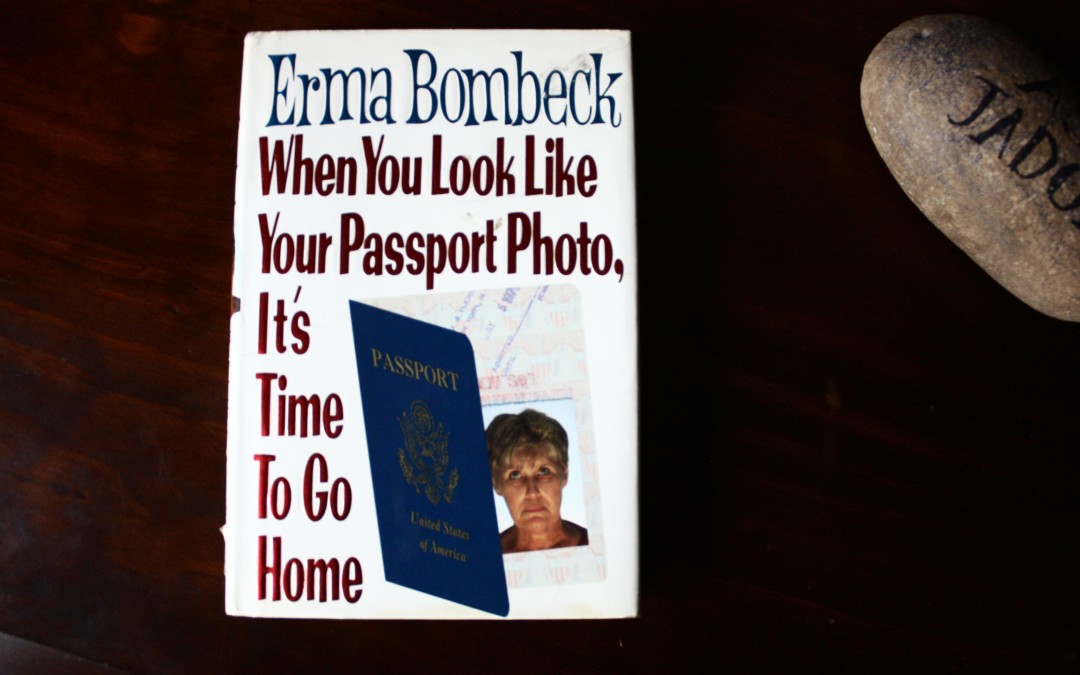

The most recent one I finished had even a hilarious title: When You Look Like Your Passport Photo, It’s Time to Go Home. I took notes copiously throughout the book, trying to study what it was about her that made her so funny.

Most of the time she uses self-deprecating humor.

When she and her husband were on a cruise ship for several days, she told a story about how all they would do was eat, eat, eat. They were growing large. Here was a response from her husband when he told her they needed to do something about all this eating and she dared ask the question, “Why?”

“Let me put it this way. If someone wants to show home movies, all you have to do is wear white slacks and bend over.

“I looked in the mirror. He was right. I was beginning to dress like the Statue of Liberty. I held out my arms and fanned the skin that hung like a stage curtain. It was only a matter of time before fourteen tourists would fit in my arm. I couldn’t go home like this.”

She uses humor to make fun of herself (and her family at times) but also employs one of my favorite humor techniques—exaggeration.

When she and her husband get lost in a foreign country, on their way to the airport, she says this to her husband:

“I don’t want to panic you, but our plane leaves in four days.”

When her husband tells her he wants to go out jogging in the African bush, this is her response:

“No one is going to feel sorry for you because you’re stupid. We’re going to ship your body home and prop it up in the Boston Marathon. It will be hours before people realize you’re not moving under your own steam.”

I laughed out loud at that one, because it creates such a humorous image, and speaks just a little bit of truth, too.

“I don’t understand people who can go abroad and come back with nothing to declare but diarrhea,” she says. This sentence is so blunt and unexpected that I could not help but laugh. I’ve been abroad. And I did come back with diarrhea.

Other self-deprecating examples:

“I was being held captive on a no-frills ship of geologists, zoologists, and botanists who cared about the preservation of the world but nothing about toilet tissue. I hate to make generalizations, but there is a definite correlation between smart people and little regard for creature comforts.”

She is saying, essentially, that because she cares about these “creature comforts,” she is one of the not-smart people.

“At nights, I joined the group in the ship’s small lounge to listen to lectures, watch slides, and make notes on what we were to see the next day. No one suspected that in college, in response to the question, ‘What is a chinook?’ I wrote in, ‘The name of the guy I just broke up with.’”

At times, Bombeck takes a popular phrase and turns it around surprisingly:

“It has always been my theory that the family that plays together gets on one another’s nerves.”

And she uses surprise as an element of her humor, as in this passage:

“Standing at the south rim of the Grand Canyon, our family looked like an ad for constipation…Our daughter was ticked off because it was four in the morning and she didn’t want to be there. Her brothers were fighting because one of them was staring at the other one, and my husband didn’t know how he could possibly be on a raft on the Colorado River for six days with only a gym bag of clothes.”

Anyone who has traveled with a family will understand where she’s coming from.

Bombeck uses real-life humor often, which draws her readers to her. Anyone who has been a parent of teenage drivers understands the following (if a little exaggerated):

“I have survived three teenage drivers: one who used cruise control in downtown traffic at five p.m., one who put on full makeup and finished her homework while driving through a construction area, and another who got a ticket for driving forty-five miles per hour…in reverse. But this was unbelievable.”

I love that phrase at the end—“this was unbelievable”—which follows something that was really unbelievable—a driver getting a ticket for driving forty-five miles per hour in reverse.

Bombeck also has a hilarious passage on people trying to make their friends and family look at vacation slides (in her time—it could be translated to showing travel pictures or posting all your travel pictures on Facebook). But you’ll have to read the book to get that passage.

Bombeck is a master at turning a witty phrase:

“You don’t even know what fear is until you are out in the bush with eleven shutter-happy hunters who load film and shoot at anything that moves.”

“One (child) ran with the bulls through the narrow streets of Pamplona and told me later so I could have a heart attack at leisure.”

“We have paid as much as $300 a day to throw up in a sink shaped like a seashell.”

“From the rear, I looked like a Disney parking lot.” (She’s looking in the mirror wearing the full expedition costume.)

But lest you think When You Look Like Your Passport Photo It’s Time to Go Home is all fun and games, Bombeck also has a serious side. She pontificates on the shared hopes of humanity:

“Once you have looked into the eyes of people in a foreign country, you realize you all want the same thing: food on your table, love in your marriage, healthy children, laughter, freedom to be. The religion, the ideology, and the government may be different but the dreams are all the same.”

And, when speaking about a particular family trip that was the last her family would take as parents and children in an essay titled “Rafting Down the Grand Canyon, she says this:

“For the first time we could remember, we were a family who gave one another space to be ourselves. We had never done that before. It was as if we all knew that this was the end of a chapter in our lives and the beginning of a new one. The umbilical cord that had bound us together as a unit for nearly two decades was about to be severed.”

“From that day on, our lives would all turn in different directions. In many ways it was like the Colorado River. It would wind and twist with a promise of a new experience at each turn of the bend. There would be smooth waters for long stretches, then suddenly a patch of rough rapids that would test us and take away our control. It would demand everything we had to hang on and get back on course again.”

She finishes this essay with:

“It would be several years before we planned another family vacation. We all had a lot of thinking and growing up to do…a lot of things to prove to ourselves. But strangely, this was the trip that we all talk about and remember, the pictures we pore over in the family albums. We have never said it to one another, but it was the last summer of the child…the last summer of the parents. From that day on, all moved to become contemporaries.”

Makes me want to pack up my family right now and take them on a vacation.